1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) notions allude to the companies’ abilities to respond to the expectations of a broad spectrum of stakeholders that present different demands. Several organizations, however, have been promoting CSR actions aiming to respond to these demands, in order to obtain competitive advantage (Archel, Husillos, Larrinaga, & Spence, 2009; Branco & Rodrigues, 2008; Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996).

CSR information reports aim to transmit social, political, and economic meaning, showing to society the organizations’ concern with social issues; strengthening the relationship between the organizations and their stakeholders; helping to mitigate conflicts, as well as to legitimate the organizations’ activities (Deegan, 2002; Neu, Warsame, & Pedwekk, 1998).

A KPMG’s (2013) study shows that the number of CSR reports published has increased, as well as the volume of the information disclosed, internationally and in Brazil. Despite this growth, it must be assessed if the respective reports provide objective information that allows for a precise estimate of the companies’ social performance (Adams, 2004; Archel, Fernández, & Larrinaga, 2008; Bouten, Everaert, Van Liedekerke, De Moor, & Christiaens, 2011; Hopwood, 2009; Tschopp & Huefner, 2015; Unerman, 2000). This reality has fostered research about the effectiveness of CSR reports in satisfying the demand for information and the actual companies’ degree of responsibility (Adams, 2004). Results have shown that CSR reports seem to have more content disclosed about objectives and intentions than on effective social actions (Hopwood, 2009). To advance in this matter, it was pointed out the need for CSR reports to incorporate more comprehensibility, completeness, and/or comprehensiveness in its information, so that they have more content regarding concrete information about accomplished social actions (Adams, 2004; Bouten et al., 2011; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996; Van Staden & Hooks, 2007).

In Brazil, studies about CSR information disclosure focus mainly on the analysis of the disclosed information volume (Leite Filho, Prates, & Guimarães, 2009; Oliveira, 2005; Viana Junior & Crisóstomo, 2016) and/or in the companies’ attributes that influence the disclosure –especially environmental information (Oliveira, Ponte Junior, & Oliveira, 2013; Oro, Renner, & Braun, 2013; Rover, Tomazzia, Murcia, & Borba, 2012)–. Therefore, it is timely the conduction of studies that assess the comprehensiveness of disclosed information, by evaluating the degree of comprehensibility of the CSR information disclosed by the Brazilian companies.

This work aims to appraise the level of comprehensiveness in CSR reports of Brazilian companies. For such approach, the degree of comprehensiveness of the reports was evaluated considering the three types of information and its correspondence with each item disclosed: vision and objectives; management actions; and performance indicators. This analysis aims to capture the comprehensiveness, or completeness, of the reports regarding information meaning and its accountability to stakeholders.

Results reveal that, although it is still low, in average there has been an advance in the comprehensiveness of CSR information disclosed by the Brazilian companies. Companies that have been putting substantial effort in the pursuit of more disclosure of their CSR concerns and sustainability –proxied by their presence in the ISE (Brazilian Sustainability Index)– present more comprehensive CSR reports. Firm ownership concentration in the hands of the main shareholder is another aspect that contributes to increase the degree of comprehensiveness in CSR reports. Additionally, the fact that the company industry is associated to high environmental risk, positively affects the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports, as well as the size and firm profitability.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. CSR disclosure

comprehensiveness in Brazil

Distinct proposals for CSR reports, that have appeared recently, aim to enhance the communication between company and society by disclosing CSR actions. Internationally, initiatives such as the model proposed by the United Nations via Global Compact; the AccountAbility’s AA1000series, and the model proposed by the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) can be mentioned (Gómez-Villegas & Quintanilla, 2012; Tschopp & Huefner, 2015). In Brazil, the Brazilian Institute of Social and Economic Analysis (Instituto Brasileiro de Análises Sociais e Econômicas – IBASE) proposed an interesting model for disclosing CSR; model that had relevant adherence by companies from 1996 to 2008 (Corrêa, Souza, Ribeiro, & Ruiz, 2012; Crisóstomo, Freire, & Vasconcellos, 2011).

Literature suggests that companies disclose CSR information for various reasons. On the one hand, they may seek to legitimize their activities by displaying a positive image to a broad spectrum of stakeholders (Archel et al., 2009; Deegan & Rankin, 1996; Quinche-Martín, 2014; Reverte, 2009). On the other hand, companies also try to respond to the stakeholders’ expectations concerning their actions, in the sense that they may contribute to society’s well-being (Morsing & Schultz, 2006; Quinche-Martín, 2014; Reynolds & Yuthas, 2008). CSR disclosure can also be a communication strategy that aims to provide answers for institutional pressures (Cuevas-Mejía, Maldonado-García, & Escobar-Váquiro, 2013; Young & Marais, 2012). Either of these motivations requires the CSR report to transmit information –in terms of volume and quality of presentation– that meets the demands of stakeholders and that allows them to properly assess the companies’ CSR action.

Regardless of the companies’ CSR disclosure report motivation or its format, it is important that it provides a release able to meet the information demands of their diverse stakeholders. In fact, the CSR report must transmit a good notion of the social and environmental impacts of each company’s activities, both when such impacts are positive and negative (Bouten et al. 2011; Gray, Kouhy, & Lavers, 1995). Therefore, the report disclosed by each company must be as complete, as well as comprehensible as possible, so that it effectively enables stakeholders to make a precise evaluation of its social responsibility. The question that has been proposed is to which degree do these reports in fact present the completeness, or comprehensiveness, needed for this external analysis process? (Adams, 2004; Archel et al., 2008; Bouten et al., 2011; Hopwood, 2009; Tschopp & Huefner, 2015; Unerman, 2000).

In this context, there has been a complaint that CSR reports tend to prioritize the disclosing of content regarding the companies’ objectives and intentions, leaving in a second place the publication of actions effectively carried out (Hopwood, 2009). This situation could occur due to an excess in the presentation of the companies’ plans and their intentions, which are developed to the detriment of space for disclosing effective actions –which may be actually little–. This possibility has created the need for disclosing effective CSR plans and sustainability actions, as well as the numbers and indicators related to them. This information about concrete actions gives more comprehensiveness to the report, making it more complete (Adams, 2004; Bouten et al., 2011; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996; Van Staden & Hooks, 2007).

Regarding the report’s comprehensiveness, the argument is that, in order to show effective CSR accountability, the information contained in the report must present a clear declaration of values, with their corresponding objectives, goals to be achieved, and report of progresses achieved (Adams, 2004; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996; Vuontisjärvi, 2006). Based on this argumentation, Bouten, Everaert, Van Liedekerke, De Moor and Christiaens (2011) suggest that, in order to show accountability on their social responsibility related actions in an effective way, companies must disclose complete, comprehensive or comprehensible information, which demands the presentation of three types of information for each revealed CSR item: (i) vision and objectives (VO); (ii) management approach (MA), and (ii) performance indicators (PI). The vision and objectives (VO) category includes information that signals each firm’s policy, goals, and values concerning the disclosed CSR item, which constitutes a first level of disclosure that Robertson and Nicholson (1996) call general rhetoric. The management approach (MA) category, in turn, describes the action or practice adopted by the company concerning certain CSR questions; category that corresponds to a second level of disclosure defined by Robertson and Nicholson (1996) as a specific effort. Finally, the performance indicators (PI) reflect the real CSR achievements, as they provide indicative measurements of the achievements, advances, or setbacks in each company’s performance regarding CSR-related matters (Bouten et al., 2011).

2.2. Hypotheses

Some works started to examine the potential of the CSR reports as the means for disclosing social responsibility activities or actions that were executed by organizations. Examples of researches in this field are the ones that were conducted in the United Kingdom (Adams, 2004; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996) and in Belgium (Bouten et al., 2011; Vuontisjärvi, 2006). These studies verified that social responsibility reports do not show a high degree of comprehensiveness and depict a predominance of corporate rhetoric, in detriment of disclosing concrete actions and performance indicators regarding CSR.

An international research developed by KPMG about corporate reports shows that about 93% of the 250 largest companies in the world disclose reports of this nature and that there is also a tendency to conduct external auditing of these reports. In Brazil, the percentage of CSR reports submitted to external evaluation is 56%, while the global average is 38% (KPMG, 2013). In December of 2011, the São Paulo Stock Exchange (BM&FBovespa) issued an External Statement recommending the listed companies to indicate in the Reference Form whether they disclose Sustainability Reports or similar document, and where the report is available. If not, they must explain why they do not do it (BM&FBovespa, 2011). This rule, baptized Report or Explain, might have contributed to the increase from 45.31% to 66.29% in the accession of companies to the sustainability disclosure reports between May of 2012 and June of 2013 (KPMG, 2013). In the Brazilian market, studies about CSR reports found results in the same direction of increase in accession and in auditing of reports, as well as more compliance to quality standards (Corrêa et al., 2012; Crisóstomo, Prudêncio, & Forte, 2017).

The evolution of the quality and comprehensiveness of the information disclosed in CSR reports of Brazilian companies might not follow a linear path in accordance to the quantity of information disclosed. However, it is pertinent the proposition that the growth in the number of reports with good compliance to quality standards, such as the GRI guidelines and the external auditing of reports, are factors that strongly contribute to the quality and comprehensiveness of the disclosed information. This information makes for the proposition of a hypothesis about the evolution of the comprehensiveness degree of CSR reports in Brazilian companies.

Hypothesis 1: There has been an advance in the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports disclosed by Brazilian companies

Companies with a higher degree of concern with CSR and sustainability actions tend to give more importance to reports that disclose information of this nature, as a way to be more transparent and pursue image and reputation gains, as well as legitimacy of their activities (Adams, 2008; Bebbington, Larrinaga-González, & Moneva-Abadía, 2008a, 2008b). This broader importance must be reflected in the quality of the report, which includes its depth, completeness, comprehensibility, or comprehensiveness.

Market indices have been proposed to evaluate the degree of the firms’ concern with CSR and sustainability actions, such as the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) of New York (USA); the FTSE4 Good of London (United Kingdom), and the JSE Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) Index of Johannesburg (South Africa) (Marcondes & Bacarji, 2010). In Brazil, there is the Corporate Sustainability Index (Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial – ISE), which has also been used as an indicator of the level of attention the company gives to social responsibility, and environmental and corporate sustainability issues.

The rationale is that companies that compose these indices would have a higher CSR and sustainability disclosure standard because of the competitive process that they go through in order to be members of the sustainability index in a certain year, and because of the higher degree of visibility they consequently have by composing the index. The proposal is that the ISE participation amplifies the market knowledge of each company commitment to sustainable development, equity, transparency, and accountability (BM&FBovespa, 2016). Under this argument, the ISE presence would grant each company a gain in image among its many stakeholders, thus facilitating the legitimacy achievement for its activities. In this context, there are results in Brazil that indicate that the ISE participation influences the voluntary disclosure of socio-environmental information (Braga, Oliveira, & Salotti, 2009; Machado, Macedo, Machado, & Siqueira, 2012; Murcia, Rover, Lima, Fávero, & Lima, 2008).

This line of thought suggests that companies that integrate the ISE index manifest more concern with the valorization of their institutional image and, in consequence, disclose CSR information in a more complete and comprehensive fashion, as formulated in hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 2: The level of comprehensiveness of CSR information disclosed by companies that compose the ISE document is higher than that of other companies

The literature has suggested that firm ownership structure might have effects on the conflicts of interests that appear between each company’s main stakeholders –shareholder, manager, and creditor–. For instance, there are results that indicate the influence of the ownership structure on the companies’ value and performance (Allen & Phillips, 2000; Villalonga & Amit, 2006), as well on the companies’ dividend policy in many ways (DeAngelo, DeAngelo, & Skinner, 2008; Harada & Nguyen, 2011; López-Iturriaga & Crisóstomo, 2010). There is also evidence that certain traits of the ownership structure affect the companies’ investment policies and capital structure (Crisóstomo & Pinheiro, 2015; Goergen & Renneboog, 2001; Schiantarelli & Sembenelli, 2000). Considering that the ownership structure interferes in various company policies, it is plausible to suggest that it might also influence the CSR policy and its respective disclosure.

Besides the pressure from society for company social responsibility, owners and managers have started to contemplate the possibility of CSR being an important tool of legitimacy, as well as a source of improvement for each company’s image and reputation; all of which would be a motivating factor to carry out projects such as those that are proposed as able to create value (Chiu & Sharfman, 2011). Large controlling shareholders are very interested in firm legitimacy, reputation, and image improvement for each company, given their superior interest in creating value for each firm in the medium and long term, differently from minority shareholders, that might prioritize a more short-term perspective. In fact, under this argument of value-creation interest in the long term, through firm image and reputation improvement due to consistent CSR actions, there are results that confirm the positive effect of ownership concentration on each company’s CSR policy (Crisóstomo & Freire, 2015; Godos-Díez, Fernández-Gago, & Cabeza-García, 2012). Specifically, in regard to the CSR disclosure degree, there are results that indicate a positive effect of ownership concentration in hands of the government (Eng & Mak, 2003).

In Brazil, the strength of the main shareholder stands out as able to influence on company’s policies. The interest in company legitimacy as well as improvement of reputation and image is very much associated with the identity of the main shareholder, and this situation can make them prioritize CSR and its respective disclosure. It is intuitive to suggest that more social and sustainability actions for the company, motivated by a pursuit of legitimacy and reputation gain, may conduct to a higher disclosure degree on these actions, which would be associated to a broader comprehensiveness of the CSR and sustainability reports, as proposed in the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 3: There is a positive relation between ownership concentration in hands of a controlling shareholder and the level of comprehensiveness on CSR reports

Society’s growing concern with environmental issues has put pressure on firm management so that, as an area of study, it brings awareness of these issues; and such management concern may also lead to improve other aspects of social responsibility. Environmentally sensitive sectors of the economy are those that involve a higher risk of environmental impact and, as such, are more susceptible to criticism and penalties regarding their activities (Reverte, 2009). This higher attention on these companies can foster a more intense social and environmental action from them, considering that they must be more aware in order to prevent environmental hazards and can also be seeking to conduct more social action in general, in the search for legitimacy and image improvement.

In Brazil, the Law 10165 of 2000, which deals with the National Environmental Policy, classified in its annex VIII the economic activities according to industry propensity to have environmental impact in three levels: low, medium, and high environmental impact potential. There are areas of the economic trade that are not classified in either of these levels. Previous studies noted that companies of more environmentally sensitive areas disclosed more social and/or environmental information, probably due to the higher visibility that these companies now have, and the need for adapting to more rigorous requirement standards concerning the relation with the natural environment (Bouten et al., 2011; Brammer & Pavelin, 2004; Crisóstomo, Souza, & Parente, 2012; Reverte, 2009).

From this discussion, it is plausible to propose that reports containing CSR information disclosed by companies from riskier industries would be more comprehensive than those of other companies with lesser potential for environmental impact, as expressed in the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 4: CSR Reports disclosed by firms from sectors with higher environmental risk, according to the National Environmental Policy, present superior levels of comprehensiveness compared to reports from other companies

The Stakeholder theoretical framework proposes that there is a virtuous cycle between CSR and company performance, under the argument that CSR actions are able to create value to the company, since society has a positive sensibility for this type of corporative action (Baron, Harjoto, & Jo, 2011; Freeman, Wicks, & Parmar, 2004; Salazar, Husted, & Biehl, 2012; Waddock & Graves, 1997). The Slack Resource Theory, which proposes that a better financial performance generates more resources availability that can be directed to CSR, is an additional argument in favor of the aforementioned virtuous cycle between profitability and CSR. In turn, more CSR action requires more disclosure, which naturally has a cost that is more easily handled by companies with more profitability. This way, more profitability might allow for more complete and comprehensive CSR reports, as hypothesized bellow.

Hypothesis 5: Profitability positively contributes to the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports

Firm bigger size has been suggested as favorable for the CSR policy due to the higher availability of resources implied, either by infrastructure or money, for the execution of social policy. Furthermore, as the company grows, it gathers more visibility and interacts with a broader group of stakeholders, facing a greater demand for CSR, as well as for disclosure of these actions, which are of interest since they will contribute to improve its reputation and pursuit of legitimacy (Andrade, Bressan, Iquiapaza, & Moreira, 2013; Artiach, Lee, Nelson, & Walker, 2010; Lourenço & Castelo Branco, 2013; Orlitzky, 2001; Ullman, 1985; Ziegler & Schröder, 2010). In this sense, it is proposed the hypothesis that larger companies will invest more in the completeness and comprehensiveness of their CSR reports as a way to better meet society’s demands for information, as synthesized in the hypothesis that follows:

Hypothesis 6: The size of the company positively influences the comprehensiveness degree of its CSR reports

3. Methodology and Sample

3.1. Methodology

The data

was analyzed through a qualitative and a quantitative approach. Initially, GRI reports

were qualitatively analyzed. Then, a quantitative analysis was conducted, including

a detailed description of the sample and the measurements used. After that, tests

for the difference in means on the degree of comprehensiveness on CSR reports were

run, and econometric models were estimated in order to assess the drivers for their

degree of comprehensiveness on CSR reports.

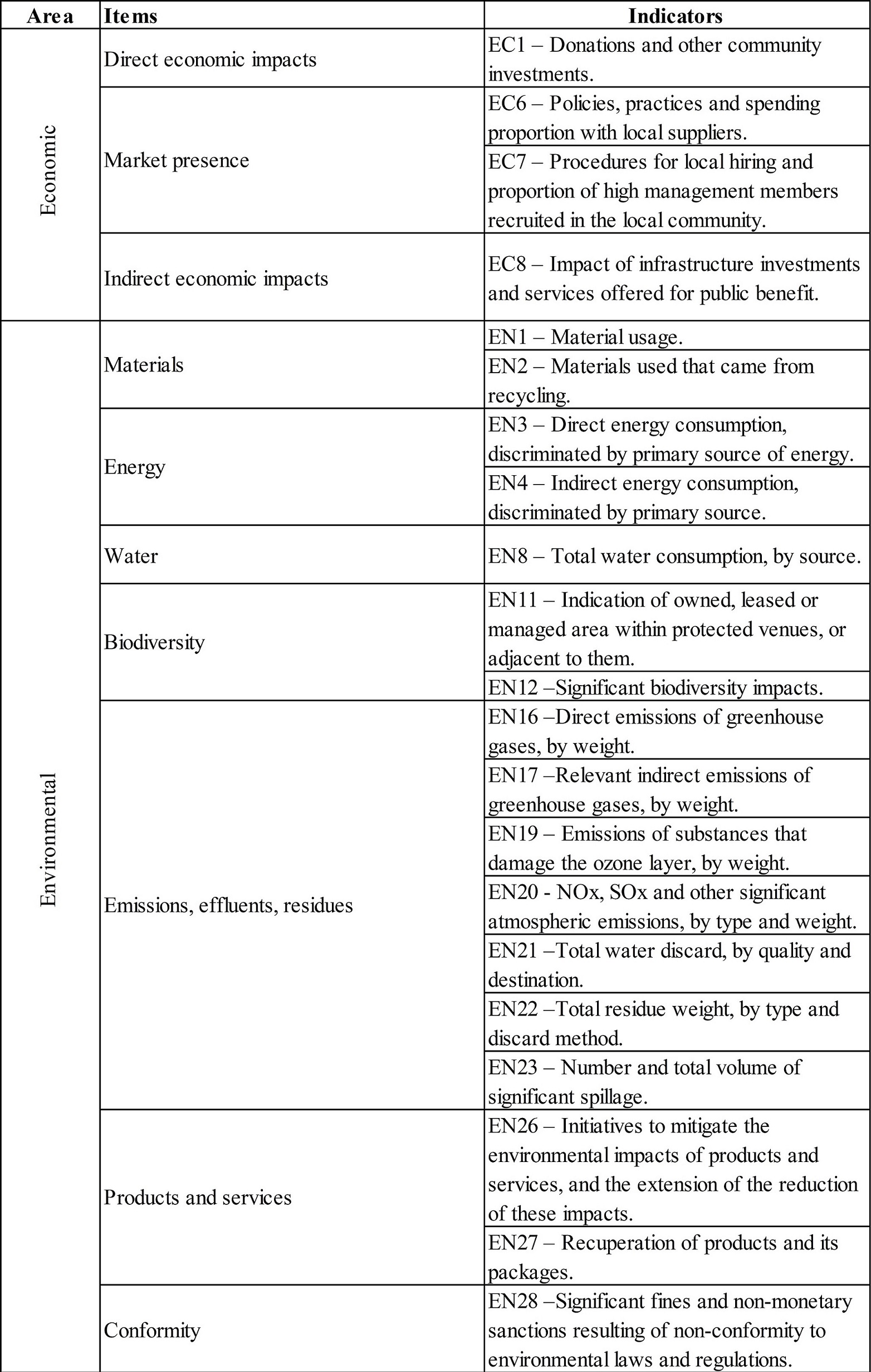

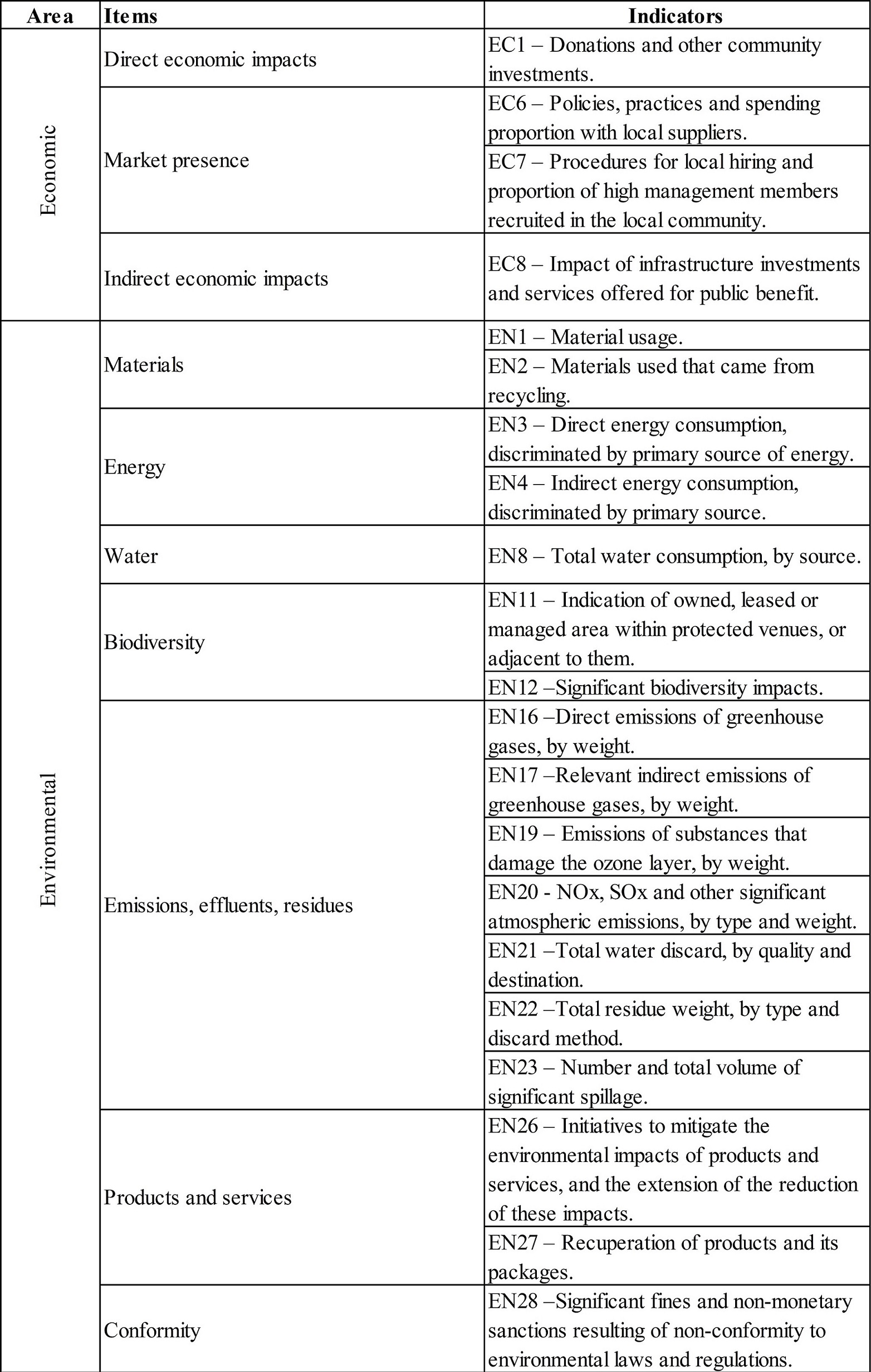

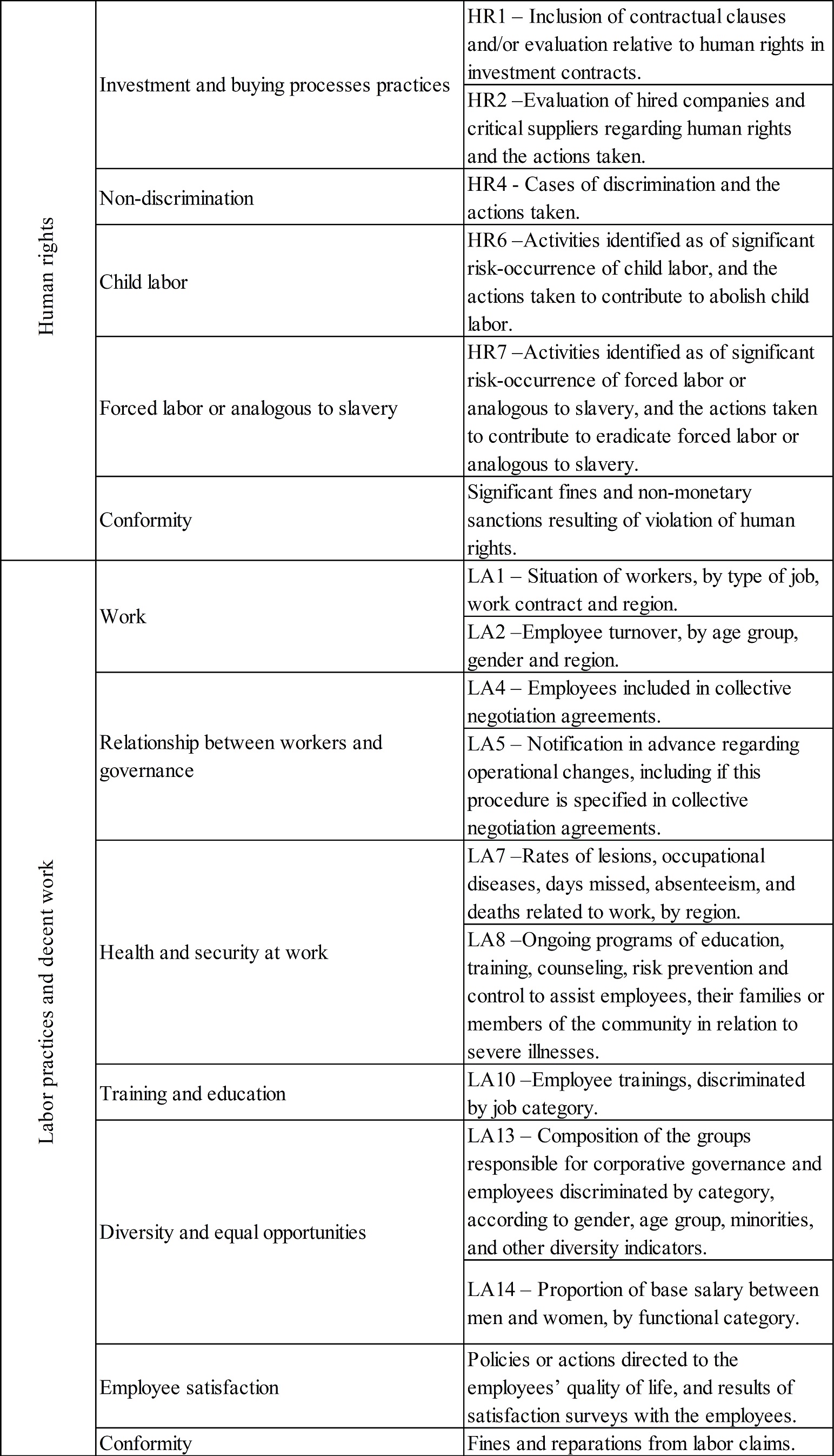

3.1.1. Content analysis

In order to obtain an indication of CSR items disclosed by companies and the comprehensiveness of the information that accompanied each item –declared in terms of vision and objectives, management approach, and performance indicators– the content analysis table developed by Bouten et al. (2011) was used. This instrument enabled us to evaluate the comprehensiveness of the information about social responsibility that was disclosed in the annual reports of the companies.

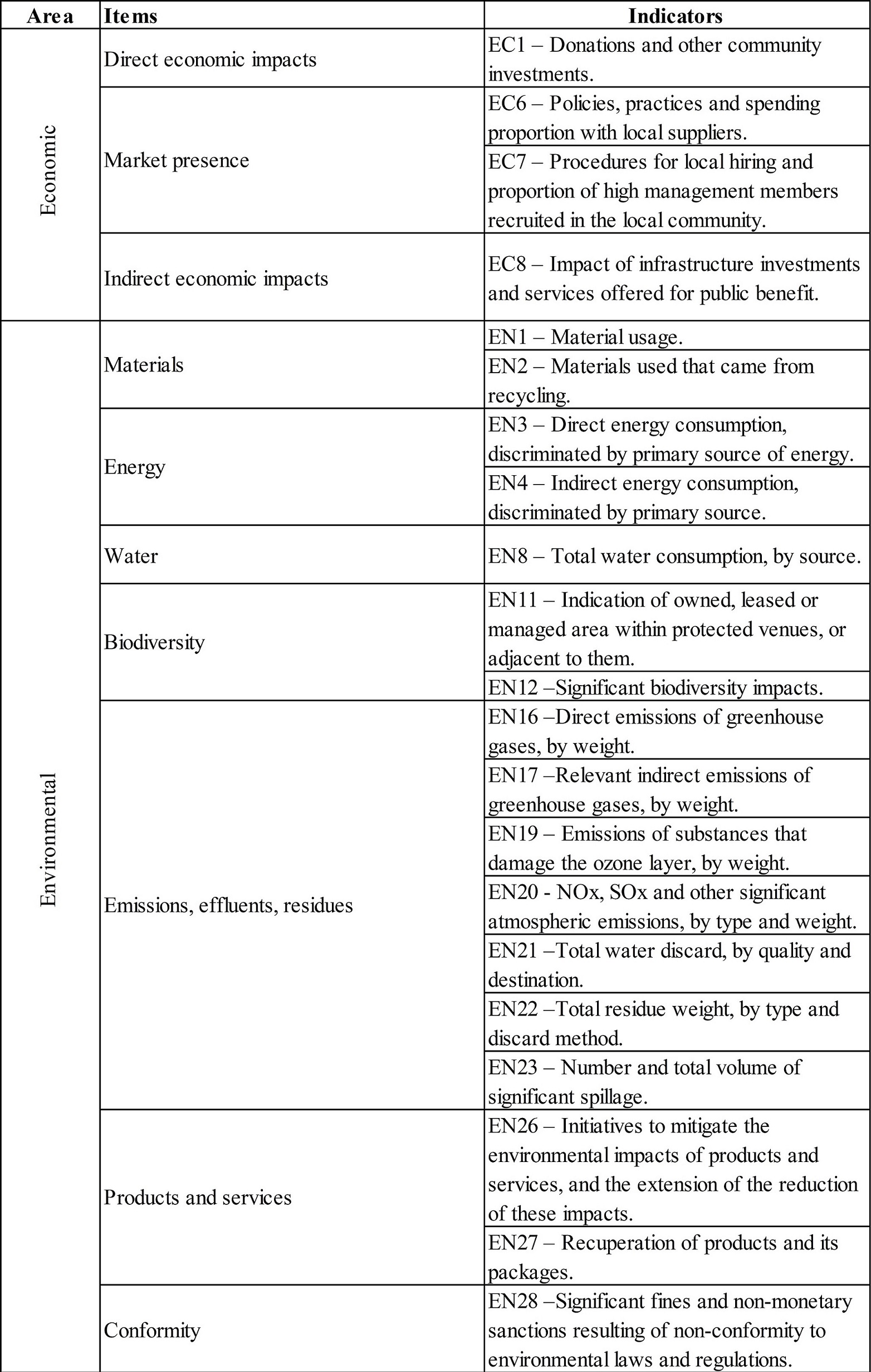

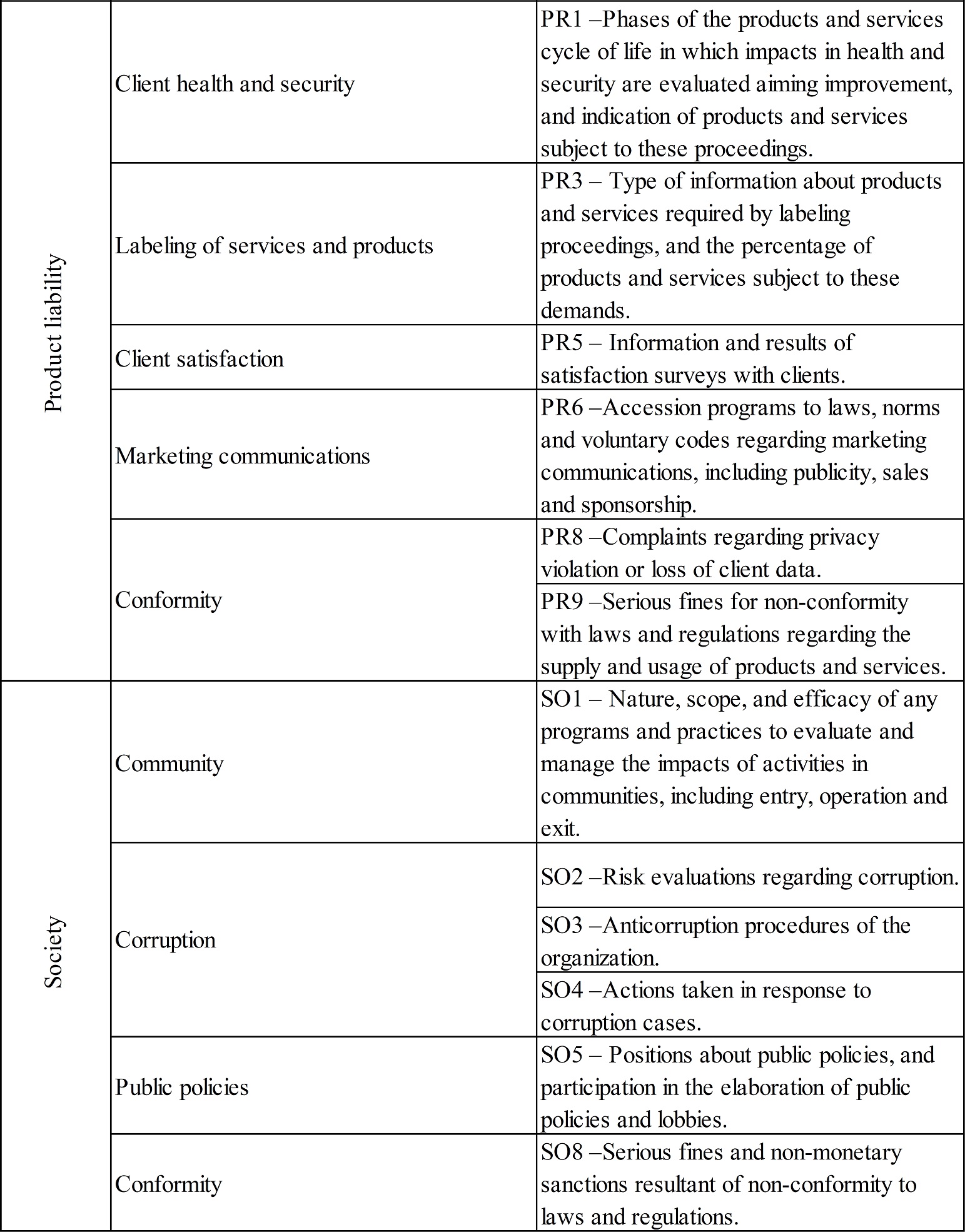

Content analysis technique requires a coding structure based in precise rules about information, representative of the content analysis characteristics, reliable and that facilitates the interpretation of the data (Bardin, 2011). The coding structure of the content analysis was oriented by the GRI Sustainability Report Guidelines, version G3, with the intent of avoiding possible disparities between the items analyzed, since the analysis contemplates reports from the period comprising from 2010 to 2013.

Figure 1 presents the coding structure used in the content analysis in the shape of a decision tree previously adopted from the work of Bouten et al. (2011). The codification tree consists of two dimensions: (i) the content, and (ii) the type of information. The dimension of content refers to the information content and comprises two levels of analysis: areas and items. The area corresponds to the sustainability performance categories defined according to the GRI Guidelines. The items correspond to the specific indicators defined for each area. The dimension type of information is intended to verify the information comprehensiveness for each disclosed item, considering the nature of the information it contains, examining if it contemplates (i) vision and objectives (VO); (ii) management approach (MA); and (iii) performance indicators (PI), which are all considered essential aspects for the effectiveness of accountability (Bouten, et al., 2011; Robertson & Nicholson, 1996; Vuontisjärvi, 2006).

Figure 1

Coding structure for the content

and the type of information disclosed

Figure 1

Coding structure for the content

and the type of information disclosed

Note: VO = vision and objectives;

MA = management approach; PI = performance indicators

Source: adapted from Bouten et al. (2011)

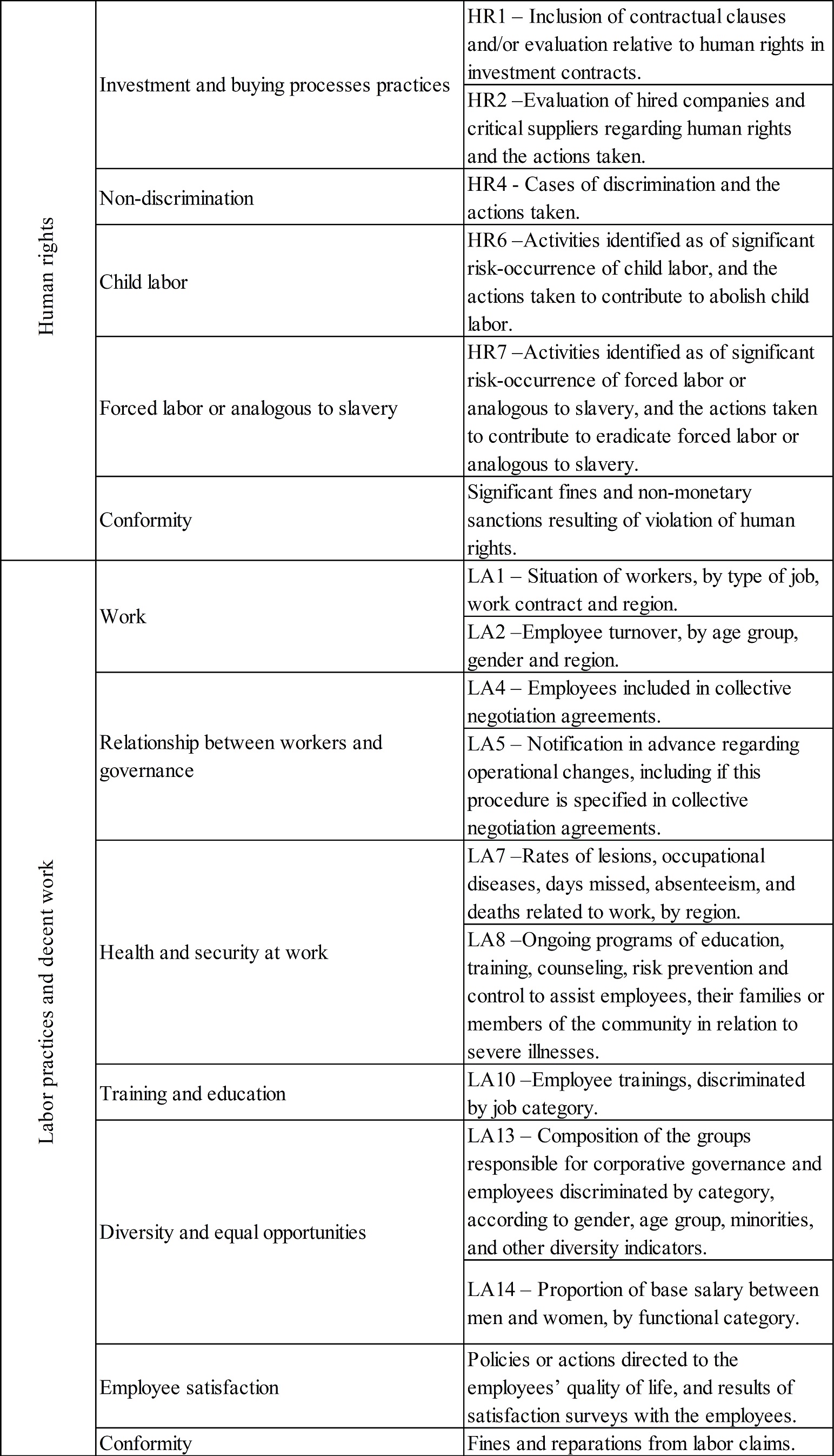

Content analysis requires the selection of a unit of analysis that can be characterized as a content segment that can be allocated to a certain category (Guthrie, Cuganesan, & Ward, 2008). In line with previous studies, this work used sentences as units of analysis (Bouten et al., 2011; Guthrie et al., 2008; Hackston & Milne, 1996). Sentences that served as scripts for coding decisions correspond to the indicators defined by the GRI Guidelines for Sustainability Reports, according to the details that are shown in the Appendix.

In order to verify the presence of an item and the type of information revealed by it in the report reading, the identification code was initially searched in the GRI Content Index (for instance, “EC1,” “EN26,” “SO1”). In those instances, when the reports did not present the GRI summary, phrase structures and key terms were used (for instance, “local suppliers,” “health and safety,” “organizational environment,” “human rights”) to locate items in them.

The verification that an item identified in the reports contemplated VO (vision and objectives) type of information, was conducted using key terms or words that denote intention, policies, values, or objectives of the company in the CSR context, such as: “The correct residue management is a commitment of,” or “The development and qualification of our collaborators are amongst our main values.” In order to verify MA (management approach) information, terms that indicate initiatives, actions, projects, and programs effectively implemented by the company were used, such as: “In 2013, we offered more than 305 thousand hours of training,” “The focus of private social investment continues to be social inclusion with emphasis in education. Among the initiatives developed in 2013, we can mention,” “US$ 415 million in funding and credits were liberated via […], the local suppliers’ development program of” (see emphasis).

Finally, information about PI (performance indicators) corresponded to the data expressed in quantitative (absolute, relative, graphic) or qualitative values that indicated progresses or deficiencies on each company’s CSR performance. As examples of PI information, we can mention: “During the year, no accidents with our own collaborators were registered;” “In 2013, we had our lowest turnover index of the past three years – 7.8%, with 9% in 2012;” “The supplier expense percentage of the surroundings in relation to the total supplier expenses was: 2011 – 3.8%, 2012 – 4.0%, 2013 – 4.9%.”

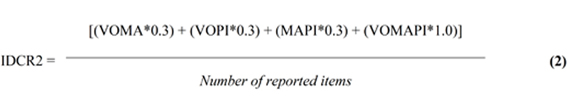

3.1.2. Index for the degree of comprehensiveness of the CSR report

Information obtained in the content analysis served as the basis for the construction of two metrics to measure the degree of comprehensiveness of the reports (IDCR), that aim to reveal the extension to which a company discloses the types of information for the items reported. In order to evaluate the degree of comprehensiveness, or completeness, of CSR reports disclosed by Belgian companies, Bouten et al. (2011) developed an index represented by the quotient between the number of items for which all three types of information (VO, MA, and PI) are disclosed, and the number of items disclosed by the company. By this formulation, only the items for which the three types of information (VO, MA, and PI) are simultaneously presented are taken into account.

Bouten et al. (2011) argue that items covered by only one of the disclosure types (VO, MA, or PI) are vague and cannot capture the contextualization of CSR disclosure. In this sense, Wood (1991) observes that formal policies might not be reflected in firm behavior or programs that denote CSR performance, as performance indicators might be due to institutional factors such as laws, regulations, changes, and adjustments in business activities, and not consequence of firm CSR decisions –which, according to McVea and Freeman (2005), consist of the sum of the company’s obligations for a specific group of stakeholders–. On the other hand, there can be social programs within the companies that have high social performance without support from any kind of formal policy (Wood, 1991). This way, the disclosure of policies, goals, and/or objectives, accompanied by performance actions or indicators associated to them, as well as the disclosure of indicators associated to policies or programs and actions, might provide some relevant information about the firm CSR. This argumentation suggests that the simultaneous disclosure of a minimum of two types of information might have the potential of meeting the stakeholders’ informative demands concerning the firm CSR.

This work uses two metrics to measure the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports: the index proposed by Bouten et al. (2011), and another proposed new index that also takes into account the item with the three types of information, as well as those items covered by two types of information (VO, MA, or PI).

The index proposed by Bouten et al. (2011) is obtained by the quotient between the number of items disclosed for which there is exposition involving the three types of information (VO, MA, or PI), and the total items about which the company disclosed information, according to equation1.

The Index for the Degree of Comprehensiveness of the Report (IDCR1) defined by this metric reveals the measure in which a company discloses all three types of information for the items it reports. This way, if a company discloses only one CSR item, and about this one item all three types of information are disclosed, the degree of comprehensiveness of the report will be 1.0. The same way, if a company reveals the totality of items considered, and all of them contemplate the three types of information, the degree of comprehensiveness of the report will also be 1.0. On the other hand, a company might publish information for a huge number of items without this reflecting in the degree of comprehensiveness of the report, if the disclosed items do not simultaneously contemplate the three types of information.

Considering that the simultaneous disclosure of two types of information is already able to transmit a certain degree of information (Wood, 1991), this work proposes an alternative metric to analyze the degree of comprehensiveness of the reports that takes into account items covered by a minimum of two types of information (VO, MA, and PI). Following the strategy of previous studies that attributed weight to the types of information disclosed (Al-Tuwaijri, Christensen, & Hughes II, 2004; Hughes, Anderson, & Golden, 2001; Wiseman, 1982), the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports disclosed by companies was obtained by the ratio between the weighted sum of the items that takes into account exactly two types of information (VO and MA; VO and PI; or MA and PI), and those that incorporate exactly the three types of information (VO, MA, and PI) with a higher weight and the total number of reported items.

In equation 2, IDCR2 is the index

for the degree of comprehensiveness of the report. VOMA is the number of

items that catch exactly information of types VO and MA. VOPI is the number

of items that get exactly information of types VO and PI. MAPI is the number of

items that catch exactly information of types MA and PI. VOMAPI is the number

of items that disclose simultaneously the three types of information, VO, MA, and

PI.

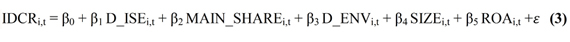

3.1.3. Model

In order to contrast the research hypotheses, tests for the difference in

means were executed according to the degree of comprehensiveness of the reports.

Mainly, econometric models were estimated, in which the degree of comprehensiveness

of the reports (IDCR1 and IDCR2) is the dependent variable. The estimated models

are based on equation 3:

In equation 3, IDCRi,t

is the degree of comprehensiveness of the

report of company i during the period t. Table 3 sums up the construction

of independent variables used in the model. D_ISE is

a dummy variable that indicates the presence

of company i in the ISE index during year t. MAIN_SHARE is the proxy for the

ownership concentration in the hands of the main shareholder. Two proxies are used

for such concentration. Firstly, it is used a dummy indicating the presence of a

major shareholder, i.e., a shareholder that holds more than 50% of the voting shares

(D_MAJOR). Alternatively, it is also used the proportion of shares in the hands

of the main shareholder (CONC1). D_ENV is a dummy

variable that is set to 1 when the firm belongs to a high-risk industry, i.e.,

an industry with high potential to cause environment damage according to the Law

10165 of 2000. The size of the company (SIZE) is proxied by the natural logarithm of

the firm total assets. The profitability is proxied by the return on assets (ROA).

Dummy variables of firm industry and year

are also included in the model.

3.2. Sample

The sample used is composed by 265 annual

observations from 98 companies listed in BM&FBovespa

that published social responsibility reports according to the GRI guidelines in

the period from 2010 to 2013. Companies whose CSR reports were available for download

in the GRI website until June 31st, 2015, were included in the sample.

The sample comprises an ample range of firm industries, which is important in such

studies (Table 1).

Table 1

Companies by economic activity

Source: own work

The option for companies listed in the stock exchange was made because public

companies have the ownership structure as a more relevant aspect. Besides, these

companies tend to adopt broader and more comprehensive information disclosure policies

in order to pursue reductions of informative asymmetry (Bouten

et al., 2011; Branco & Rodrigues, 2008). Additionally,

financial data are timely available and subject to auditing processes. Finally,

the option for CSR reports that follow the GRI guidelines was made because of the

worldwide recognition they have been attaining and the continuous increase of its

use as a tool for communicating the companies’ responsible behavior before the stakeholders, as well as the structured

format according to guidelines, principles, and indicators that allow for a more

adequate analysis of the information about CSR performance in various dimensions

(Brown, De Jong, & Levy, 2009; Nikolaeva & Bicho, 2011).

4. Results

4.1. Evolution of

the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports

Table 2 shows the number of reports that disclose at least one information

item (vision and objectives, management approach, or performance indicator) regarding

CSR practices in each GRI sustainability dimension. Results show that CSR reports

disclosed by Brazilian companies via GRI have a higher proportion of information

disclosed than of non-disclosure for all sustainability dimensions. The less contemplated

is the economic sustainability dimension,

maybe due to the fact that companies might be prioritizing more specific social

and environmental aspects of sustainability, which may be seen as the main objective

of the report. It must be noted, in this sense, the highlighted number of reports

with information about the dimension of labor practices and decent work (99.2%),

and as well as environmental issues (97.7%).

Table 2

Proportion of information disclosed

in CSR reports for each GRI sustainability dimensions

Source: own work

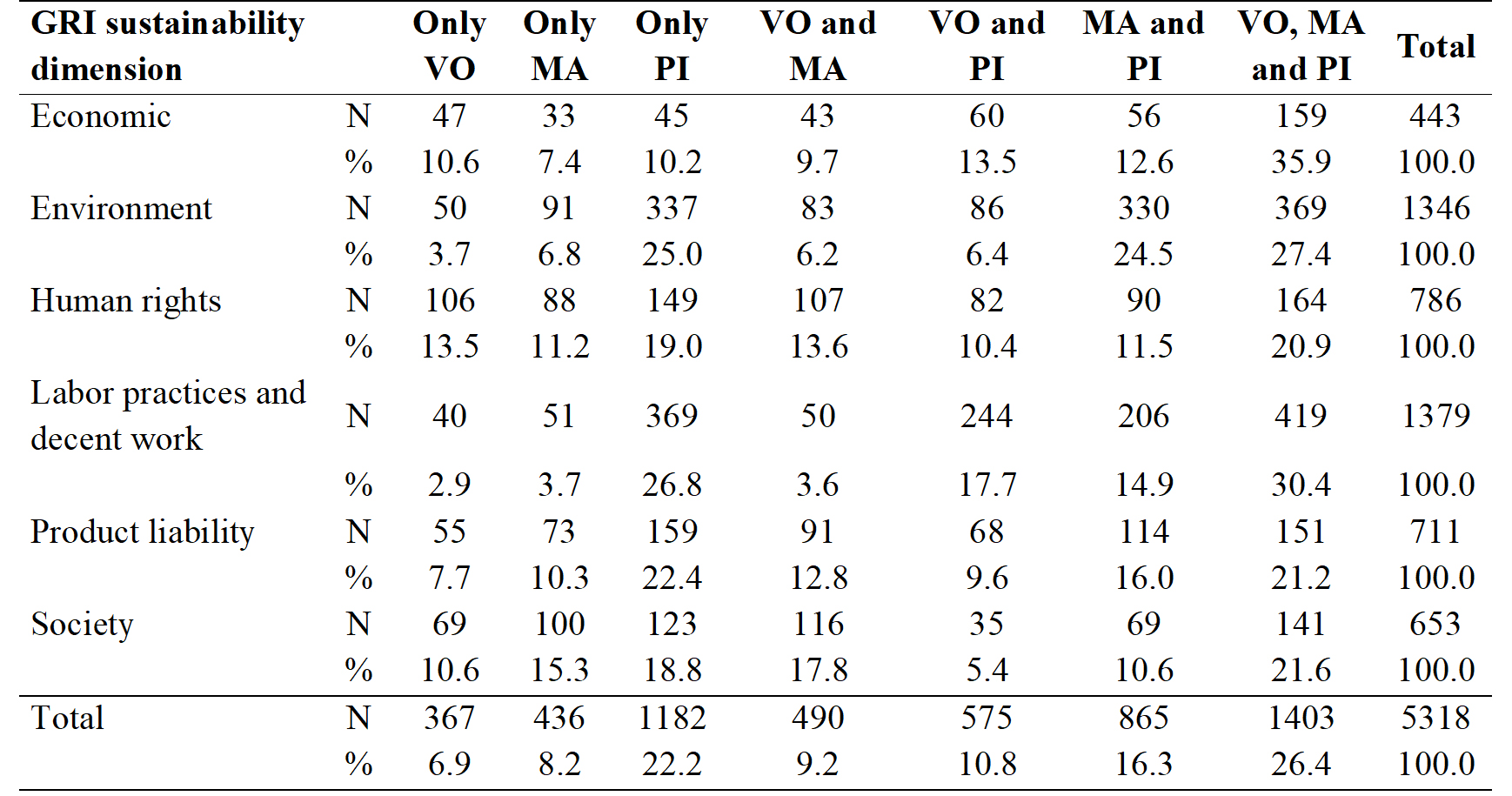

Table 3 presents the frequency of reported

items of all GRI sustainability dimensions, and the type of information disclosed

about each one. Results indicate that there is a higher proportion of disclosure

for the three types of information (vision and objectives, management approach,

performance indicator) when compared to non-disclosure. The higher proportion of

information on the social and environmental performance indicator (PI) is worth

mentioning, reaching 75.7%. That means a possible trend for the disclosure of concrete

information on CSR.

Table 3

Frequency of CSR items and type of information disclosed

Source: own work

Table 4 contains the types of information disclosed for each sustainability

dimension defined by the GRI. A positive result is that the largest proportion of

the disclosed items (26.4%) presents the three types of information (VO, MA, and

PI). 62.7% of the reports exhibits information containing two or three types of

information (VO and MA; VO and PI; MA and PI; and VO, MA, and PI). Regarding disclosed

information covered by only one type of information (VO or MA, or PI), information

of the PI (performance indicators) type stands out in comparison to the other two,

in the opposite direction of Belgian companies, that prioritize information about

specific actions according to Bouten et al. (2011).

Table 4

General vision of the types of

information disclosed per GRI sustainability dimension

Source: own work

The economic sustainability

dimension presents a higher degree of comprehensiveness according to the proportion

of items covered by information of two or three types, which corresponds to 71.7%

(sum of VO and MA; VO and PI; MA and PI; and VO, MA, and PI), followed by the sustainability

dimensions labor practices and decent work

(66.6%), and environment (64.5%),

in line with the results found by Bouten et al. (2011)

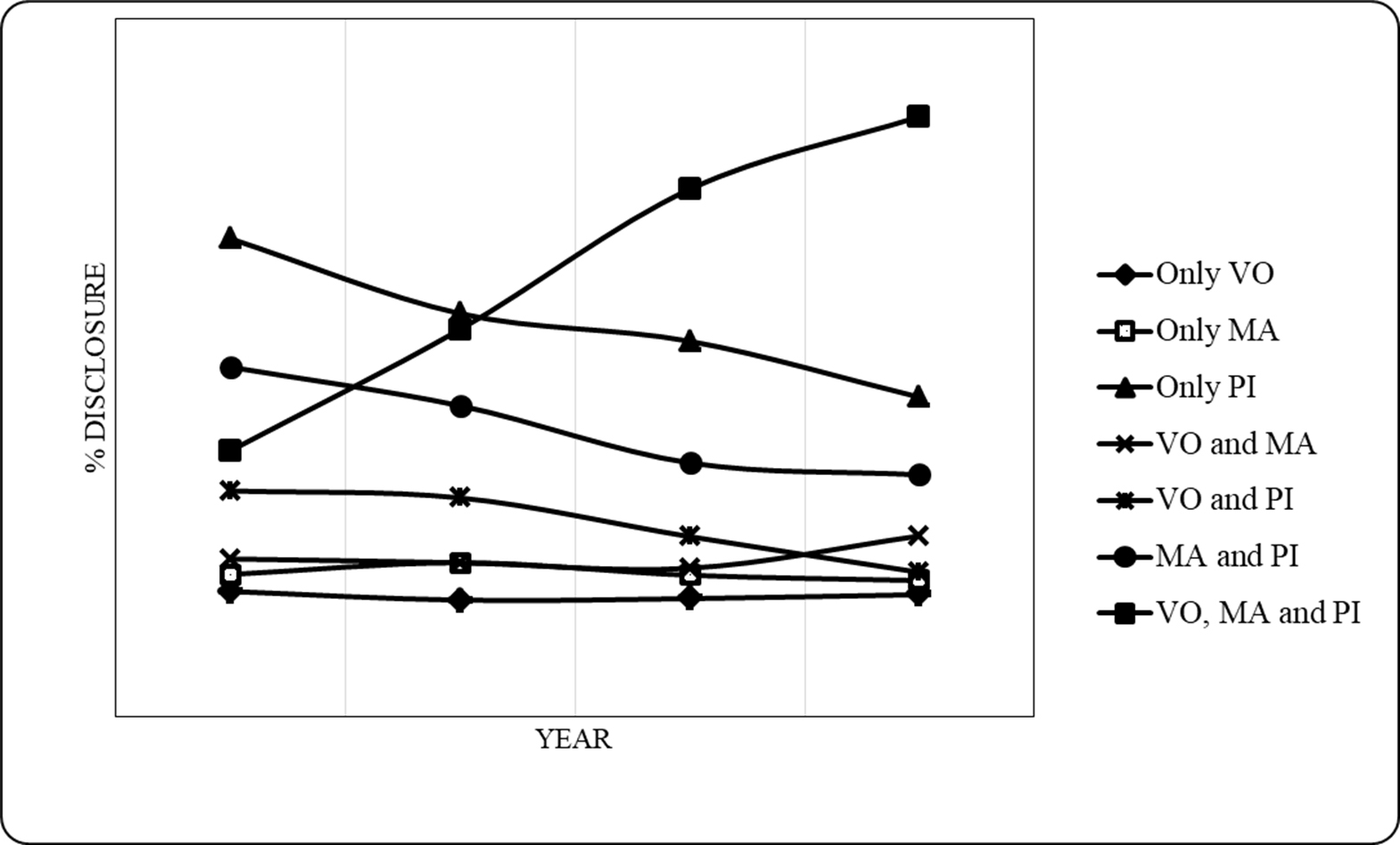

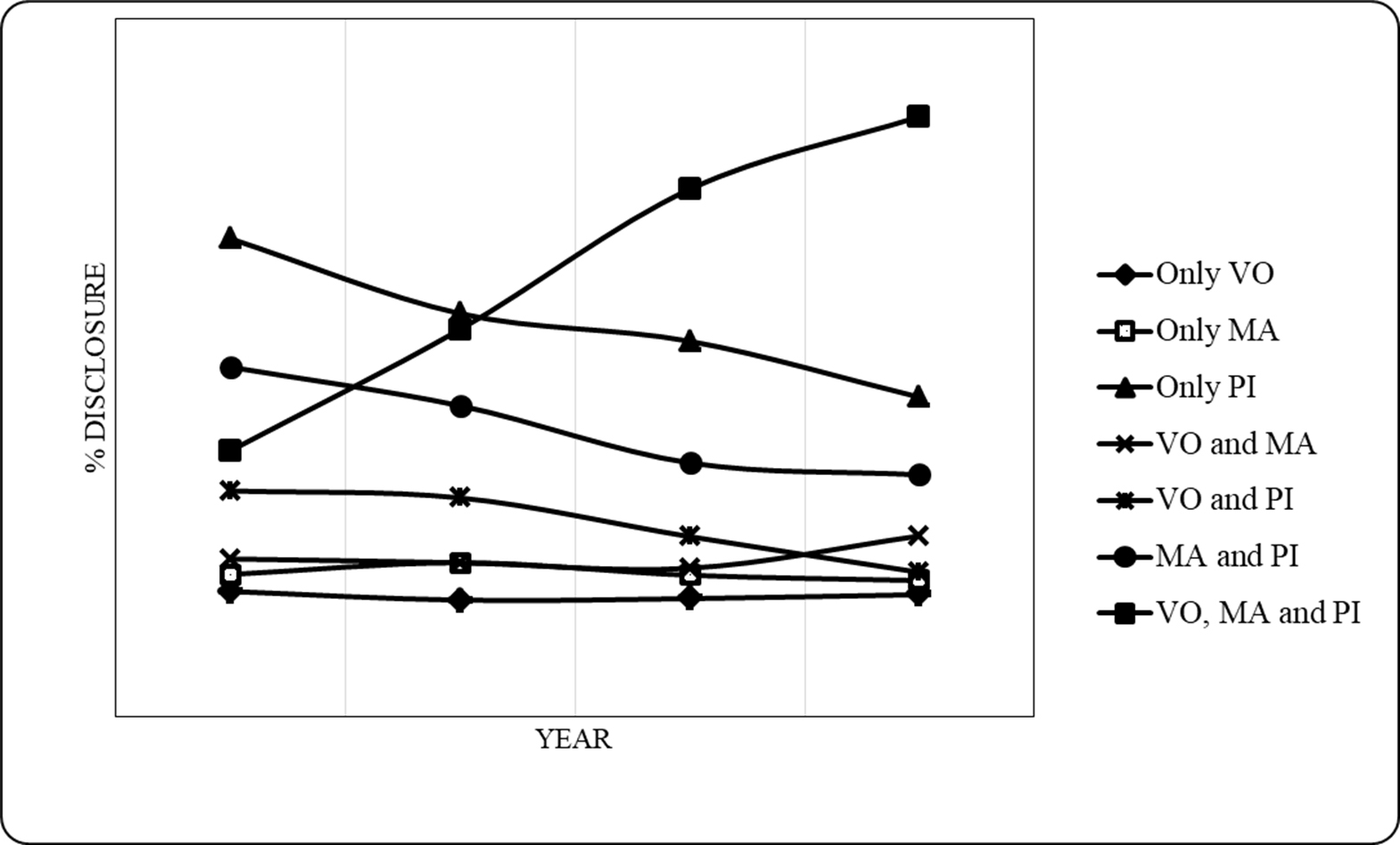

in Belgium. Figure 2 shows the evolution of the types of information disclosed in

CSR reports and its combinations during the period of 2010 to 2013.

Figura 2

Evolution of the types of information

in the period of 2010 to 2013

Figura 2

Evolution of the types of information

in the period of 2010 to 2013

Source: own work

It can be noticed from graphic 1 that the proportion of CSR items covered by information of three types (VO, MA and PI) had relevant and consistent growth during the analyzed period, in contrast to the decline, or maintenance, of items that present only one or two types of information. This denotes a trend of improvement in the comprehensiveness degree of CSR reports. Such evaluation is deepened using the comprehensiveness indices (IDCR1 and IDCR2).

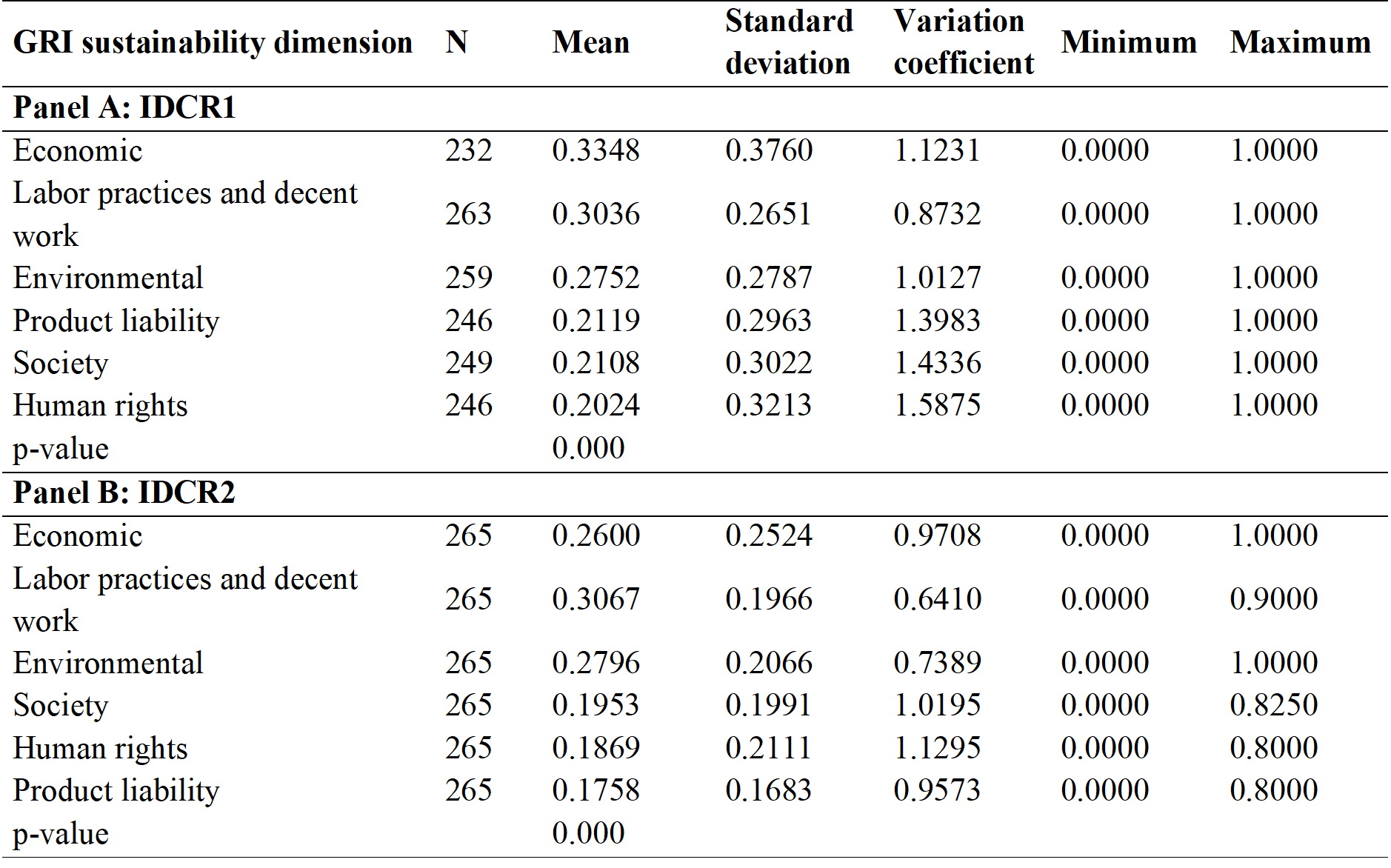

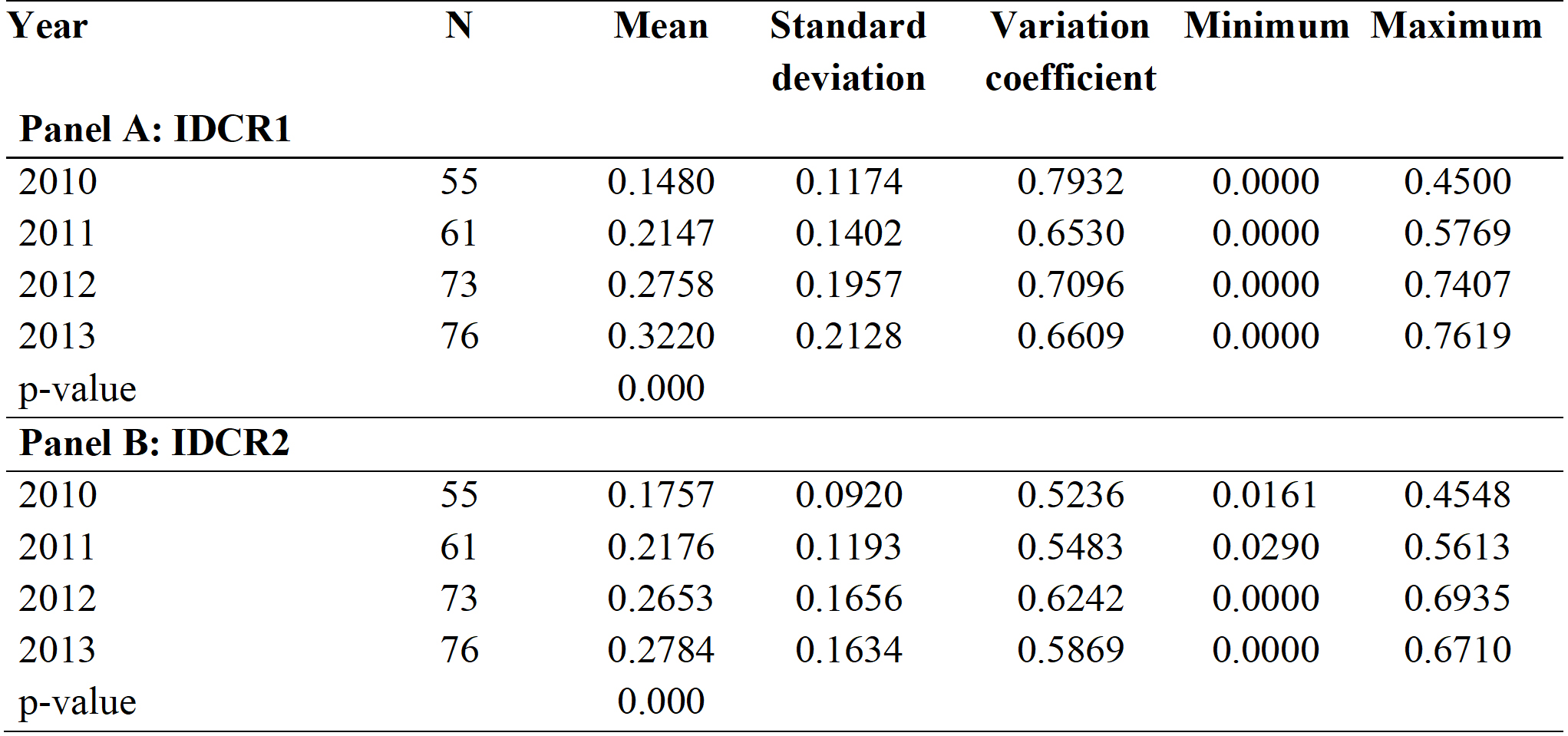

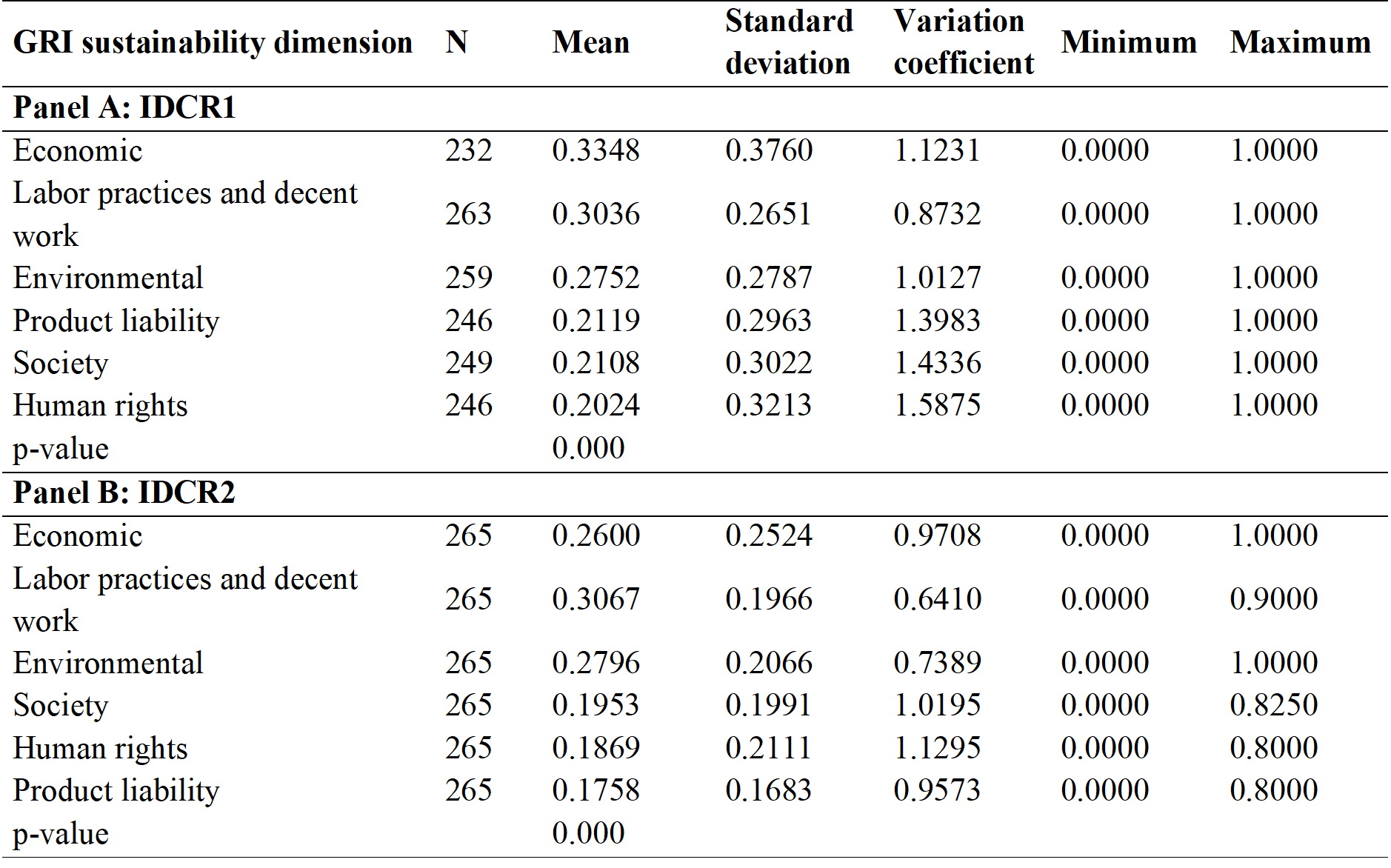

Table 5 presents the descriptive statistics of the comprehensiveness index of CSR information per GRI sustainability dimension, measured by both metrics proposed (Equations 1 and 2). On the one hand, as seen in the panel A, the IDCR1 index considers comprehensive the item that incorporates the three types (VO, MA, and PI). On the other hand, as seen in panel B, IDCR2 takes into account items that contemplate information of two types (VO and MA; VO and PI; MA and PI) or of three types (VO, MA, and PI) for each item disclosed.

The higher proportion of items in some dimensions previously observed in table 4, is observed in the index for the comprehensiveness of CSR reports exhibited in table 5. In fact, the test for the difference in means (F) among the indexes in GRI sustainability dimensions shows that there are differences among the average index of each sustainability dimension. In reality, there are CSR sustainability dimensions more covered by the reports disclosed by Brazilian companies. As in the proportion of items disclosed, the economic, labor practices, and decent work, as well as environmental dimensions, seem to present superior degrees of comprehensiveness.

Table 5

Average index for the degree of

comprehensiveness of CSR report per GRI sustainability dimension

Note:test F for the difference in means among GRI sustainability dimensions

(Anova)

Source: own work

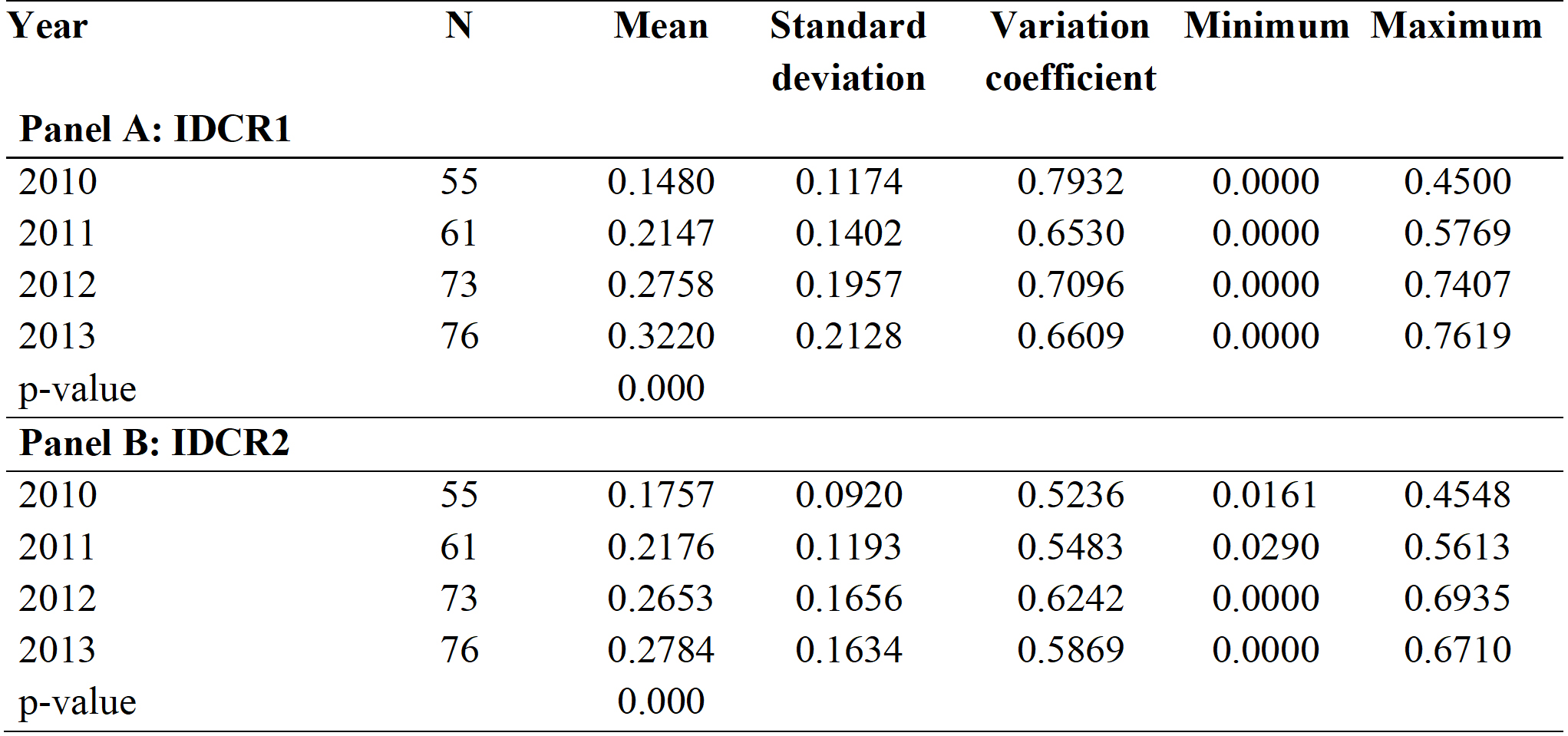

Data exhibited in table 6 indicates that the average degree

of comprehensiveness of the information present in the Brazilian companies’ CSR

reports (IDCR1 and IDCR2) has increased during the period. By both metrics used

(IDCR1 and IDCR2), an average growth in the index for comprehensiveness of the reports

can be observed along the period of study. The test F for the difference in means

among the years (Anova) showed that indeed there is a

difference in mean annual values of the

index for comprehensiveness. The average degree

of the index of comprehensiveness is actually superior in more recent periods.

Table 6

Index for the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports per year measured

by both comprehensiveness metrics (IDCR1 and

IDCR2)

Note:test F for the difference in means among the years (Anova)

Source: own work

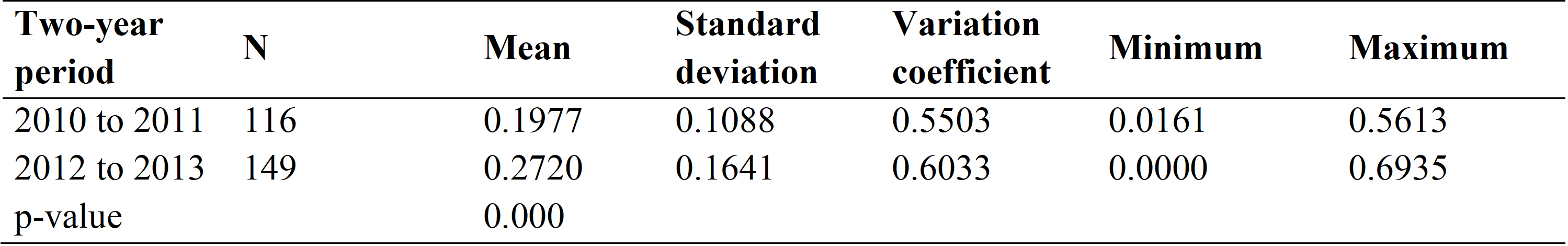

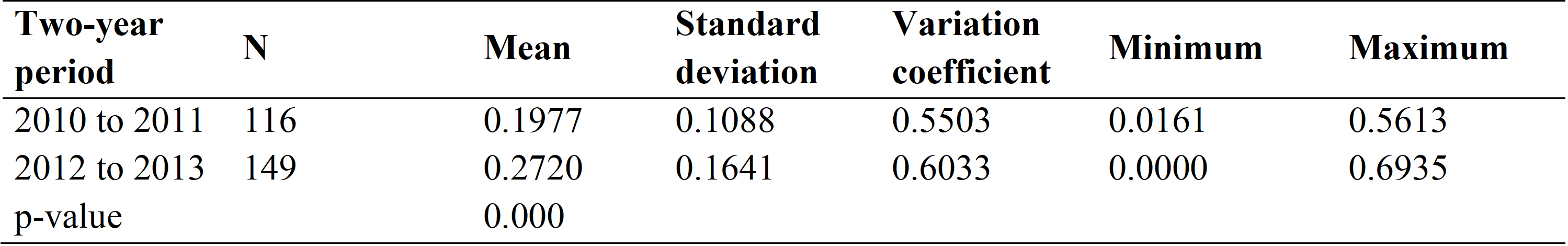

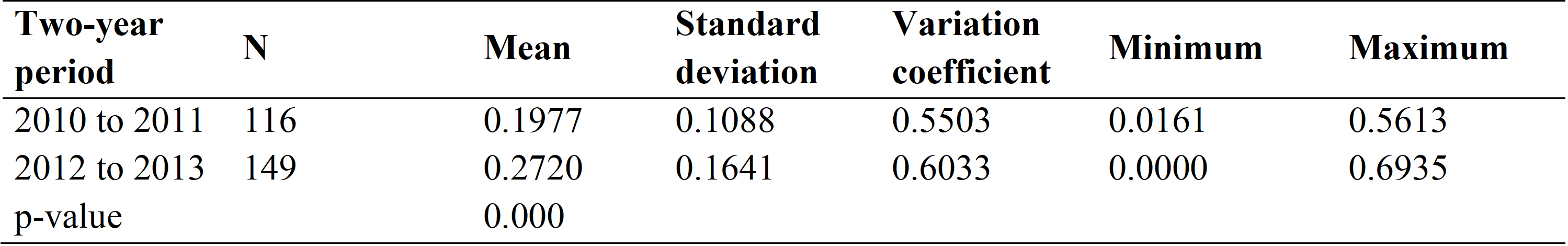

In addition to the annual comparison, the degree of comprehensiveness of

the reports was also compared between periods of two years using the t-test. The

results confirm the superiority of the average index of comprehensiveness in more

recent periods (Table 7).

Table 7

Degree of comprehensiveness of

CSR reports for every two years

Note:t-test for the difference in means

Source: own work

Results exhibited in tables 6 and 7 support the proposition of hypothesis

1, that the degree of comprehensiveness of the CSR information disclosed by Brazilian

companies has evolved throughout the years. This means that companies have developed

in the direction of improvement of the quality of the information disclosed in their

CSR reports. More than a natural evolution of the CSR disclosure process, it is

possible that the aforementioned BM&FBovespa bulletin

Report or Explain has been an additional

factor for the increase in the degree of comprehensiveness of the information disclosed

in the latest two-year period.

4.2. Driving factors of the degree of comprehensiveness

in CSR reports

According to the hypotheses proposed, it was suggested that some firm attributes

might interfere in the degree of comprehensiveness of the CSR report: company presence

in the ISE index, existence of a major shareholder, high risk firm industry as established

by the Law 10165 of 2000, as well as firm profitability and size. Table 8 brings an

initial analysis by comparing the average index for the degree of comprehensiveness

in CSR reports, measured by both metrics proposed (IDCR1 and IDCR2), between firms listed in the ISE index and non-participant firms.

From these results, it can already be noted that, in fact, the index for comprehensiveness

in CSR reports of the ISE firms is higher for both metrics used. This is a strong

indicator that belonging to the ISE might actually be a factor that stimulates a

higher completeness of the CSR report, as suggested by hypothesis 2 (Table 8: Panels

A and B).

Table 8

Comparison of the degree of comprehensiveness

of reports from ISE-participant and non-participant companies

Note:t-test for the difference in means

Source: own work

A comparative analysis of the average degree of comprehensiveness in CSR

reports between companies with and without a major shareholder shows that this degree

is higher for companies that have one major shareholder by both metrics used (Table

9: Panels A and B). This result points towards the direction of what was proposed

in hypothesis 3, signaling that a controlling shareholder tends to invest more in

CSR and in the respective disclosure, in order to gain reputation and improve firm

image.

Table 9

Degree of comprehensiveness of

reports by type of propriety

Note:T-test for the difference in means

Source: own work

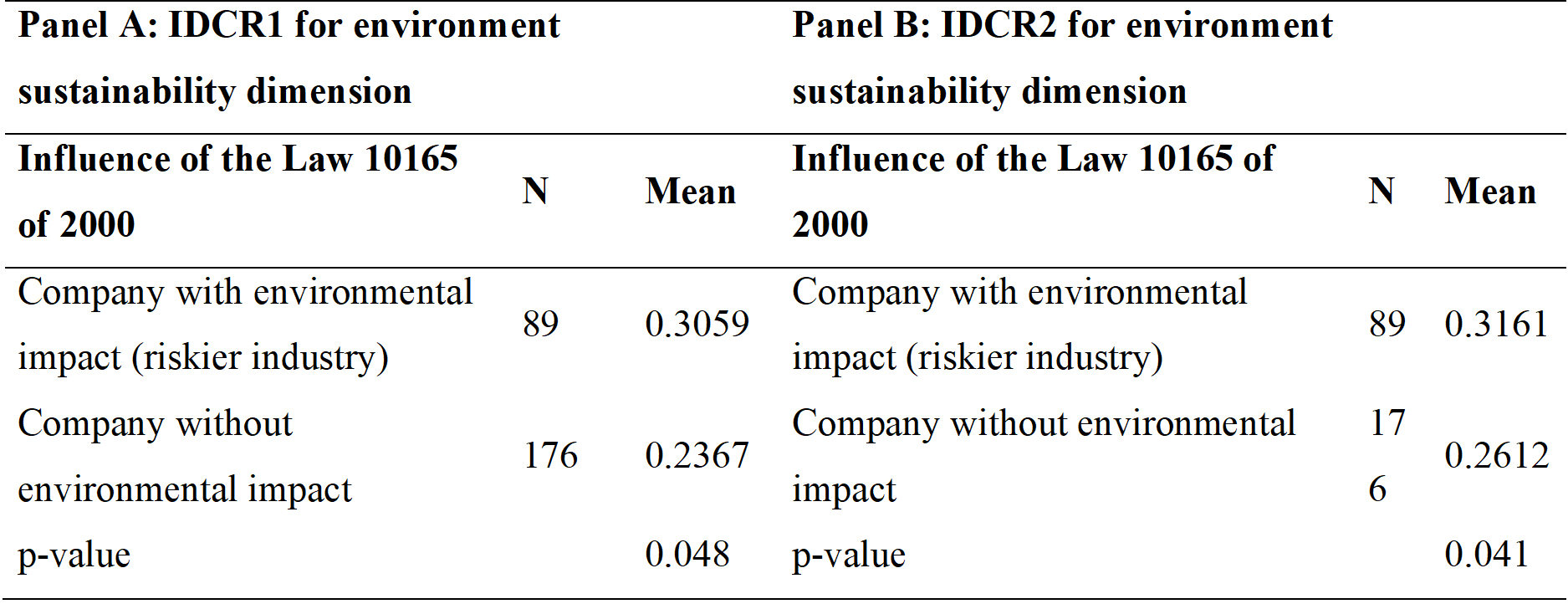

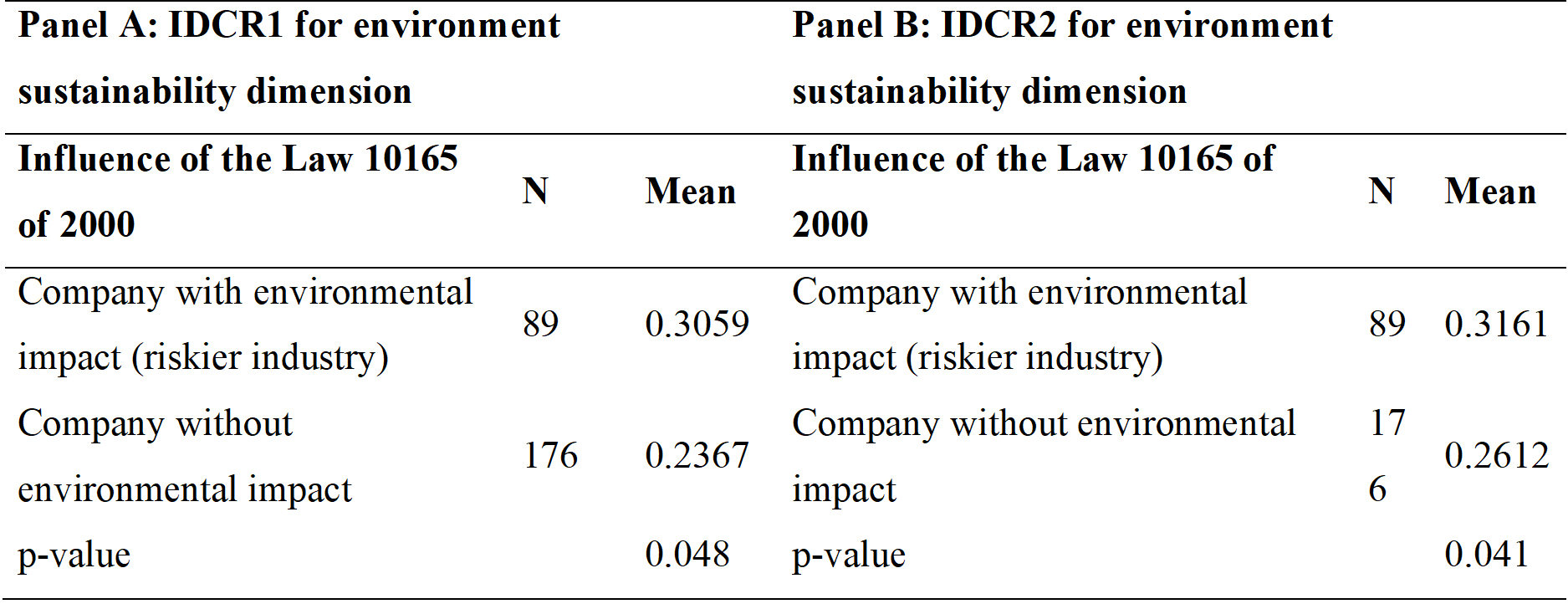

Table 10 contains results of the comparison of comprehensiveness degree average

in CSR reports between companies considered environmentally impactful according

to the Law 10165 of 2000. It is noted that statistically there is no significant

difference between the average degree of comprehensiveness in CSR reports from companies

from riskier industries when compared to those not from high risk industries, as

proposed by hypothesis 4.

Table 10

Comparison of degree of comprehensiveness

of CSR information between companies identified or not by the Law 10165 of 2000

Note:t test for the difference in means

Source: own work

The analysis

of the specific index for the degree of comprehensiveness for the environmental

issue –i.e., an index that considers the comprehensiveness of the report

taking into account only the environment sustainability dimension– was done to deepen

this analysis. Results shown in table 11 denote a higher degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports for companies from environment riskier

industries, as suggested by hypothesis 4.

Table 11

Index for the degree of comprehensiveness in CSR report of environment sustainability

dimension

Note:T-test for the difference in means

Source: own work

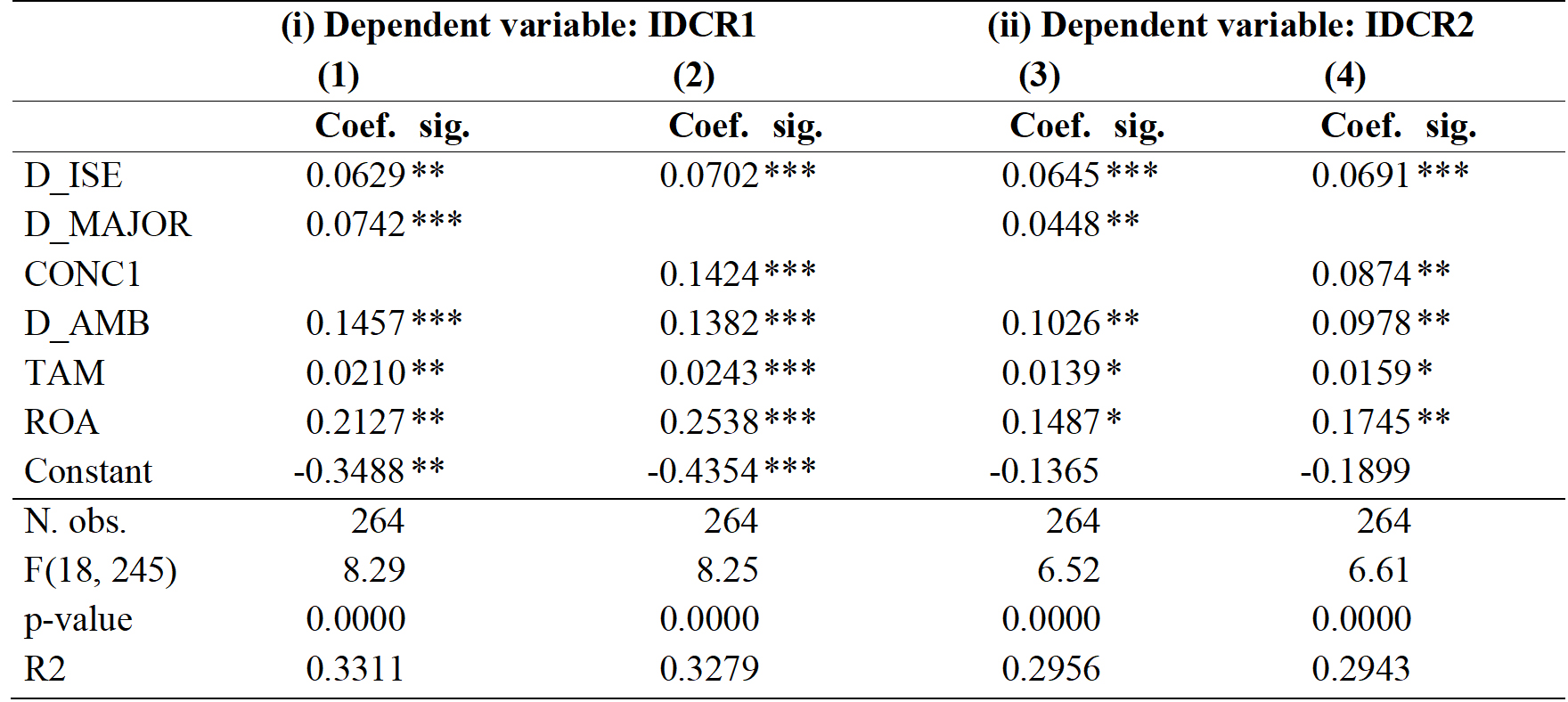

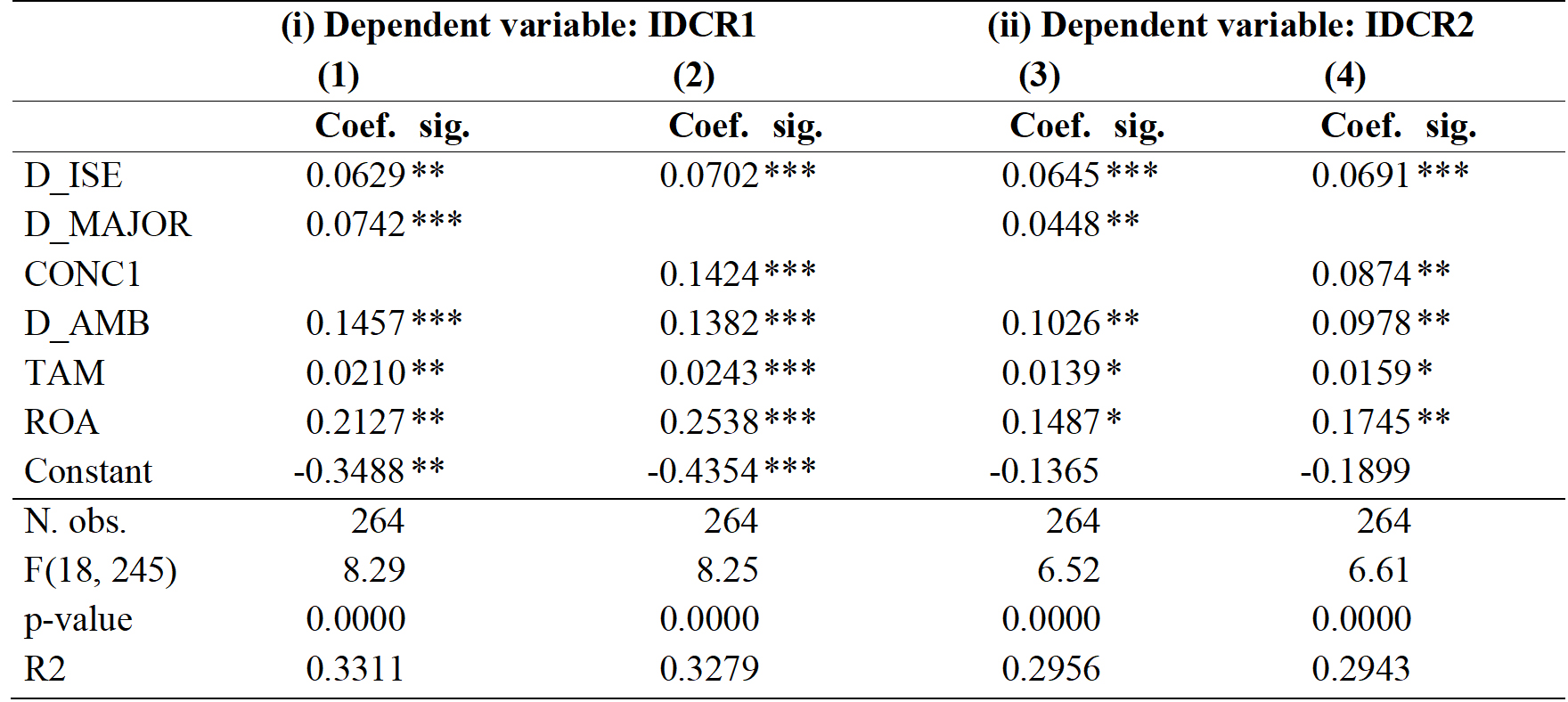

Table 12 shows the results of the estimates of models proposed in equation 3 that have the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports as dependent variable. The findings go in the same direction as those obtained by the tests for the difference in means between company groups. First of all, it can be observed that the presence in the ISE index is a company attribute that has a very positive effect on the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports, as hypothesized. In fact, being listed in the ISE (D_ISE) seems to be able to stimulate a broader disclosure of CSR and sustainability actions, because of the company’s larger visibility and the search for gain on image and reputation, as well as to seek legitimacy, as suggested in hypothesis 2.

In this same line of argumentation about the objective, the ownership concentration held by the main shareholder is another attribute of the company that contributes to increase the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports, as proposed by hypothesis 2. This positive effect is observed with the use of the two proxies proposed, which are: the presence of a major shareholder (D_MAJOR) (Table 12: Models 1 and 3), and the proportion of ownership concentrated in hands of the main shareholder (CONC1) (Table 12: Models 2 and 4). A controlling shareholder, besides tending to have a long-term perspective in the company ownership, has his/her name very much associated with the company, which is a strong motivating factor to pursue gaining in image and reputation for the company as proposed under hypothesis 3.

As foreseen in hypothesis 4, the fact that the company is considered potentially aggressive to the environment according to the Brazilian environmental law (D_AMB) contributes positively for a higher degree of comprehensiveness in CSR reports. The fact that the firm is listed as a high environment risk company according to its sector actually seems to be a factor that stimulates –or even forces– the company to present CSR reports with a higher degree of comprehensiveness.

Also, as theoretically foreseen, firm size and profitability of the company has a positive influence on the comprehensiveness degree of CSR reports.

Table 12

Models for explaining the degree

of comprehensiveness of CSR reports in Brazil

Note:models estimated by ordinary least squares with standard errors

robust to heteroskedasticity.

Coefficients exhibited with respective level of significance. ***, **, * denote

statistical significance of the coefficients at 0.01, 0.05, and 0.1 levels.

Source: own work

5. Conclusions

This study made an analysis of the comprehensiveness of CSR information disclosed by Brazilian companies, based on social responsibility reports that follow the GRI guidelines for sustainability reports. The work defined comprehensive as the contextualized disclosure that comprises information about vision and objectives, management actions, and performance indicators associated with the CSR items. This way, a more comprehensive report is the one that presents more information, therefore, consisting of a more complete, or more comprehensible, report. The reports’ comprehensiveness was analyzed via a content analysis technique that resulted in the definition of an indicative index for the degree of comprehensiveness of the CSR report.

The research used 265 annual reports of corporative social responsibility, elaborated according to GRI guidelines, from 98 Brazilian companies listed in BM&FBovespa during the period from 2010 to 2013. Results show that, in fact, there are firm attributes that interfere in the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports of Brazilian companies. Besides that, it was also noted a significant evolution in the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports. The evolution in the comprehensiveness degree of CSR reports of Brazilian companies was observed by verifying a degree of comprehensiveness significantly higher in more recent periods.

Despite the progress in the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports, it is clear that there is still a low comprehensiveness degree in CSR reports in Brazil. The measurement of the degree of comprehensiveness takes into account vision and objectives (VO), management approach (MA), and performance indicators (PI). It is observed that companies tend to report more information regarding the execution of effective actions of social performance, as performance indicators and management approach, in detriment of vision and objectives. Thus, it can be said that Brazilian companies still have to advance in disclosing their behavior regarding CSR.

About the firm attributes that influence the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports, there are in fact company attributes that matter in this context. As suggested, there is evidence that companies more concerned with sustainability –here included environmental, social, and management aspects, brought together by their presence in the ISE– present a higher degree of comprehensiveness in CSR reports. Companies that compose the ISE index, in fact, fill many requirements associated to its social and sustainability concerns. Companies with such traits tend to elaborate better CSR reports that will, therefore, be more comprehensive and complete. This attention to CSR reports might have a positive effect on the legitimacy of firm activities, as well as on firm reputation and image.

Ownership concentration in hands of the main shareholder is also another company attribute that contributes to increase the degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports. This positive effect of ownership concentration on the quality of CSR disclosure possibly comes from the controlling shareholder’s influence on the company’s policies, and his/her interest in the legitimacy and the improvement of the firm image that, in Brazil, is very much associated with the reputation of the shareholder himself/herself. It is possible to suggest that the firm social and sustainability action, motivated by the search for legitimacy and gain of reputation, leads to extensive sustainability disclosure of these actions in companies with highly concentrated ownership in hands of the main shareholder, resulting in a higher degree of comprehensiveness of CSR reports.

It is also important to report that companies from industries considered to have higher environmental impact present, according to the Law 10165 of 2000, a higher level of comprehensiveness in the disclosure of information on the specific environmental sustainability dimension. Although the Law 10165 of 2000 does not mention disclosing of social information, the fact that it lists a group of firm industries more potentially aggressive to the environment might motivate these companies to have more effective environmental concerns, as the literature has suggested. In this sense, this possible enforcement might also have an effect in the quality of CSR reports that, this way, tend to be more comprehensive, or complete, in the disclosure of information concerning environmental aspects.

Results obtained with this work amplify the knowledge about the voluntary disclosure of CSR information, since it assesses the disclosure of a group of companies that follow GRI guidelines, which nowadays constitute the main reference for disclosure in the field of corporative social responsibility in Brazil. The work also contributes to the criticism of CSR reports, adding empirical evidence for the quality of disclosed information and, still, for the advancement of studies related to the disclosure of CSR actions, by identifying types of information that might better describe the social operation practices and the assessment of results of these actions, in view of the efficacy of communication with the stakeholders.

References

Adams, C. A. (2004). The ethical, social and environmental reporting: Performance portrayal gap. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 17(5), 731-757.

Adams, C. A. (2008). A commentary on: Corporate social responsibility reporting and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(3), 365-370.

Al-Tuwaijri, S. A., Christensen, T. E., & Hughes II, K. E. (2004). The relations among environmental disclosure, environmental performance, and economic performance: A simultaneous equations approach. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 29(5-6), 447-471.

Allen, J. W., & Phillips, G. M. (2000). Corporate equity ownership, strategic alliances, and product market relationships. Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2791-2815.

Andrade, L. P., Bressan, A. A., Iquiapaza, R. A., & Moreira, B. C. M. (2013). Determinantes de Adesão ao Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial da BM&FBOVESPA e sua Relação com o Valor da Empresa. Revista Brasileira de Finanças, 11(2), 181-213.

Archel, P., Fernández, M., & Larrinaga, C. (2008). The organizational and operational boundaries of triple bottom line reporting: A survey. Environmental Management, 41(1), 106-117.

Archel, P., Husillos, J., Larrinaga, C., & Spence, C. (2009). Social disclosure, legitimacy theory and the role of the state. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 22(8), 1284-1307.

Artiach, T., Lee, D., Nelson, D., & Walker, J. (2010). The determinants of corporate sustainability performance. Accounting and Finance, 50(1), 31-51.

Bardin, L. (2011). Análise de conteúdo (1 ed.). Lisboa: Ediçoes 70.

Baron, D. P., Harjoto, M. A., & Jo, H. (2011). The economics and politics of corporate social performance. Business and Politics, 13(2), 1-46.

Bebbington, J., Larrinaga-González, C., & Moneva-Abadía, J. M. (2008a). Legitimating reputation / the reputation of legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(3), 371-374.

Bebbington, J., Larrinaga-González, C., & Moneva-Abadía, J. M. (2008b). Corporate social reporting and reputation risk management. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 21(3), 337-361.

BM&FBovespa (2011). Comunicado Externo 017/2011-DP de 23 de dezembro de 2011. Proposta de adesão ao modelo “Relate ou Explique” para relatórios de sustentabilidade ou similares para empresas listadas (Vol. 1). São Paulo: BM&FBovespa.

BM&FBovespa (2016). Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial - ISE 10 Anos. Retrieved from http://mediadrawer.gvces.com.br/publicacoes/original/ise10anos_v-03-16-1.pdf

Bouten, L., Everaert, P., Van Liedekerke, L., De Moor, L., & Christiaens, J. (2011). Corporate social responsibility reporting: A comprehensive picture? Accounting Forum, 35(3), 187-204.

Braga, J. P., Oliveira, J. R. S., & Salotti, B. M. (2009). Determinantes do nível de divulgação ambiental nas demonstrações contábeis de empresas brasileiras. Revista de Contabilidade UFBA, 3(3), 81-95.

Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2004). Building a good reputation. European Management Journal, 22(6), 704-713.

Branco, M. C., & Rodrigues, L. (2008). Factors influencing social responsibility disclosure by Portuguese companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 83(4), 685-701.

Brazil (2000). Lei 10165. Brazil, 27 of December of 2000. Retrieved from http://www.mma.gov.br/port/conama/legiabre.cfm?codlegi=323

Brown, H. S., De Jong, M., & Levy, D. L. (2009). Building institutions based on information disclosure: lessons from GRI’s sustainability reporting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 17(6), 571-580.

Chiu, S. C., & Sharfman, M. (2011). Legitimacy, visibility, and the antecedents of corporate social performance: An investigation of the instrumental perspective. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1558-1585.

Corrêa, R., Souza, M. T. S., Ribeiro, H. C. M., & Ruiz, M. S. (2012). Evolução dos níveis de aplicação de relatórios de sustentabilidade (GRI) de empresas do ISE/Bovespa. Sociedade, Contabilidade e Gestão, 7(2), 24-40.

Crisóstomo, V. L., & Freire, F. S. (2015). The influence of ownership concentration on firm resource allocations to employee relations, external social actions, and environmental action. Review of Business Management (Revista Brasileira de Gestão de Negócios), 17(55), 987-1006.

Crisóstomo, V. L., Freire, F. S., & Vasconcellos, F. C. (2011). Corporate social responsibility, firm value and financial performance in Brazil. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(2), 295-309.

Crisóstomo, V. L., & Pinheiro, B. G. (2015). Estrutura de Capital e Concentração de Propriedade da Empresa Brasileira. Revista de Finanças Aplicadas, 4(2015), 1-30.

Crisóstomo, V. L., Prudêncio, P. A., & Forte, H. C. (2017). An Analysis of the Adherence to GRI for Disclosing Information on Social Action and Sustainability Concerns. In A. Belal & S. Cooper (Eds.), Advances in Environmental Accounting & Management: Social and Environmental Accounting in Brazil (Vol. 6, pp. 69-103). Bigley: Emerald Publishing Limited.

Crisóstomo, V. L., Souza, J. L., & Parente, P. H. N. (2012). Possível efeito regulatório na responsabilidade socioambiental da empresa brasileira em função da Lei n°10.165/2000. Revista de Gestão Social e Ambiental, 6(3), 157-170.

Cuevas-Mejía, J. J., Maldonado-García, S., & Escobar-Váquiro, N. (2013). Aproximación a los factores que influyen en la divulgación de información sobre CSR en empresas de América Latina. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 14(34), 91-131.

DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Skinner, D. J. (2008). Corporate payout policy. Foundations and Trends in Finance, 3(2-3), 95-287.

Deegan, C. (2002). The legitimising effect of social and environmental disclosures – A theoretical foundation. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 15(3), 282-311.

Deegan, C., & Rankin, M. (1996). Do Australian companies report environmental news objectively? An analysis of environmental disclosures by firms prosecuted successfully by the Environmental Protection Authority. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9(2), 50-67.

Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65-91.

Eng, L. L., & Mak, Y. T. (2003). Corporate governance and voluntary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22(4), 325-345.

Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder Theory and “The Corporate Objective Revisited”. Organization Science, 15(3), 364-369.

Godos-Díez, J. L., Fernández-Gago, R., & Cabeza-García, L. (2012). Propiedad y control en la puesta en práctica de la CSR. Cuadernos de economía y dirección de la empresa, 15(1), 1-11.

Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. (2001). Investment Policy, Internal Financing and Ownership Concentration in the UK. Journal of Corporate,7(3,September), 257-284.

Gómez-Villegas, M., & Quintanilla, D. A. (2012). Los informes de responsabilidad social empresarial: su evolución y tendencias en el contexto internacional y colombiano. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 13(32), 121-158.

Gray, R., Kouhy, R., & Lavers, S. (1995). Corporate social and environmental reporting: A review of the literature and a longitudinal study of UK disclosure. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 8(2), 47-77.

Guthrie, J., Cuganesan, S., & Ward, L. (2008). Industry specific social and environmental reporting: The Australian Food and Beverage Industry. Accounting Forum, 32(1), 1-15.

Hackston, D., & Milne, M. J. (1996). Some determinants of social and environmental disclosures in New Zealand companies. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 9(1), 77-108.

Harada, K., & Nguyen, P. (2011). Ownership concentration and dividend policy in Japan. Managerial Finance, 37(4), 362-379.

Hopwood, A. G. (2009). Accounting and the environment. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(3), 433-439.

Hughes, S. B., Anderson, A., & Golden, S. (2001). Corporate environmental disclosures: Are they useful in determining environmental performance? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 20(3), 217-240.

KPMG. (2013). Pesquisa Internacional da KPMG sobre Relatórios de Responsabilidade Corporativa: Sumário Executivo (Vol. 1). KPMG (Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler).

Leite Filho, G. A., Prates, L. A., & Guimarães, T. N. (2009). Análise os Níveis de Evidenciação dos Relatórios de Sustentabilidade das Empresas Brasileiras A+ do Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) no Ano De 2007. Revista de Contabilidade e Organizações, 3(7), 43-59.

López-Iturriaga, F. J., & Crisóstomo, V. L. (2010). Do leverage, dividend payout and ownership concentration influence firms’ value creation? An analysis of Brazilian firms. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 46(3), 80-94.

Lourenço, I. C., & Castelo Branco, M. (2013). Determinants of corporate sustainability performance in emerging markets: The Brazilian case. Journal of Cleaner Production, 57(15), 134-141.

Machado, M. A. V., Macedo, M. Á. S., Machado, M. R., & Siqueira, J. R. M. (2012). Análise da relação entre investimentos socioambientais e a inclusão de empresas no Índice de Sustentabilidade Empresarial - (ISE) da BM&FBovespa. Revista de Ciências da Administração, 14(32), 141-156.

Marcondes, A. W., & Bacarji, C. D. (2010). ISE – Sustentabilidade no Mercado de Capitais (1st ed., Vol. 1). São Paulo: Report Editora LTDA.

McVea, J. F., & Freeman, R. E. (2005). A names-and-faces approach to stakeholder management: How focusing on stakeholders as individuals can bring ethics and entrepreneurial strategy together. Journal of Management Inquiry, 14(1), 57-69.

Morsing, M., & Schultz, M. (2006). Corporate social responsibility communication: stakeholder information, response and involvement strategies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(4), 323-338.

Murcia, F. D., Rover, S., Lima, I., Fávero, L. P. L., & Lima, G. A. S. F. (2008). ‘Disclosure Verde’ nas Demonstrações Contábeis: Características da Informação Ambiental e Possíveis Explicações para a Divulgação Voluntária. Revista UnB Contábil, 11(1-2), 260-278.

Neu, D., Warsame, H., & Pedwekk, K. (1998). Managing public impressions: Environmental disclosures in annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 23(3), 265-282.

Nikolaeva, R., & Bicho, M. (2011). The role of institutional and reputational factors in the voluntary adoption of corporate social responsibility reporting standards. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 136-157.

Oliveira, J. A. P. (2005). Uma avaliação dos balanços sociais das 500 maiores. RAE-eletrônica, 4(1), 1-19.

Oliveira, M. C., Ponte Junior, J. E., & Oliveira, O. V. (2013). Corporate social reporting practices of French and Brazilian companies: A comparison based on institutional theory. Revista de Contabilidade e Organizações, 18, 61-73.

Orlitzky, M. (2001). Does firm size confound the relationship between corporate social performance and firm financial performance? Journal of Business Ethics, 33(2), 167-180.

Oro, I. M., Renner, S., & Braun, M. (2013). Informações de natureza socioambiental: análise dos balanços sociais das empresas integrantes do índice de sustentabilidade empresarial da BM&FBovespa. Revista de Administração UFSM, 6(Edição Especial), 247-262.

Quinche-Martín, F. L. (2014). Desresponsabilización mediante la ‘responsabilidad social’: una evaluación retórica a las ‘cartas de los presidentes’ presentes en tres informes de responsabilidad social empresarial en Colombia. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 15(37), 153-185.

Reverte, C. (2009). Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure ratings by Spanish listed firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(2), 351-366.

Reynolds, M., & Yuthas, K. (2008). Moral discourse and corporate social responsibility reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 78(1), 47-64.

Robertson, D. C., & Nicholson, N. (1996). Expressions of corporate social responsibility in U.K. firms. Journal of Business Ethics, 15(10), 1095-1106.

Rover, S., Tomazzia, E. C., Murcia, F. D., & Borba, J. A. (2012). Explicações para a divulgação voluntária ambiental no Brasil utilizando a análise de regressão em painel. Revista de Administração - RAUSP, 47(2), 217-230.

Salazar, J., Husted, B., & Biehl, M. (2012). Thoughts on the evaluation of corporate social performance through projects. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(2), 175-186.

Schiantarelli, F., & Sembenelli, A. (2000). Form of ownership and financial constraints: Panel data evidence from flow of funds and investment equations. Empirica, 27(2), 175-192.

Tschopp, D., & Huefner, R. J. (2015). Comparing the evolution of CSR Reporting to that of Financial Reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(3), 565-577.

Ullman, A. A. (1985). Data in search of a theory: A critical examination of the relationships among social performance, social disclosure, and economic performance of US firms. Academy of Management Review, 10(3), 540-557.

Unerman, J. (2000). Methodological issues - Reflections on quantification in corporate social reporting content analysis. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 13(5), 667-681.

Van Staden, C. J., & Hooks, J. (2007). A comprehensive comparison of corporate environmental reporting and responsiveness. The British Accounting Review, 39(3), 197-210.

Viana Junior, D. B. C., & Crisóstomo, V. L. (2016). Nível de Disclosure Ambiental das Empresas Pertencentes aos Setores Potencialmente Agressivos ao Meio Ambiente. Contabilidade, Gestão e Governança, 19(2), 254-273.

Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership, control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385-417.

Vuontisjärvi, T. (2006). Corporate social reporting in the European context and human resource disclosures: An analysis of Finnish companies. Journal of business ethics, 69(4), 331-354.

Waddock, S. A., & Graves, S. B. (1997). The corporate social performance - financial performance link. Strategic Management Journal, 18(4), 303-319.

Wiseman, J. (1982). An evaluation of environmental disclosures made in corporate annual reports. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 7(1), 53-63.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. The Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691-718.

Young, S., & Marais, M. (2012). A multi-level perspective of CSR reporting: The implications of national institutions and industry risk characteristics. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 20(5), 432-450.

Ziegler, A., & Schröder, M. (2010). What determines the inclusion in a sustainability stock index? A panel data analysis for European firms. Ecological Economics, 69(4), 848-856.

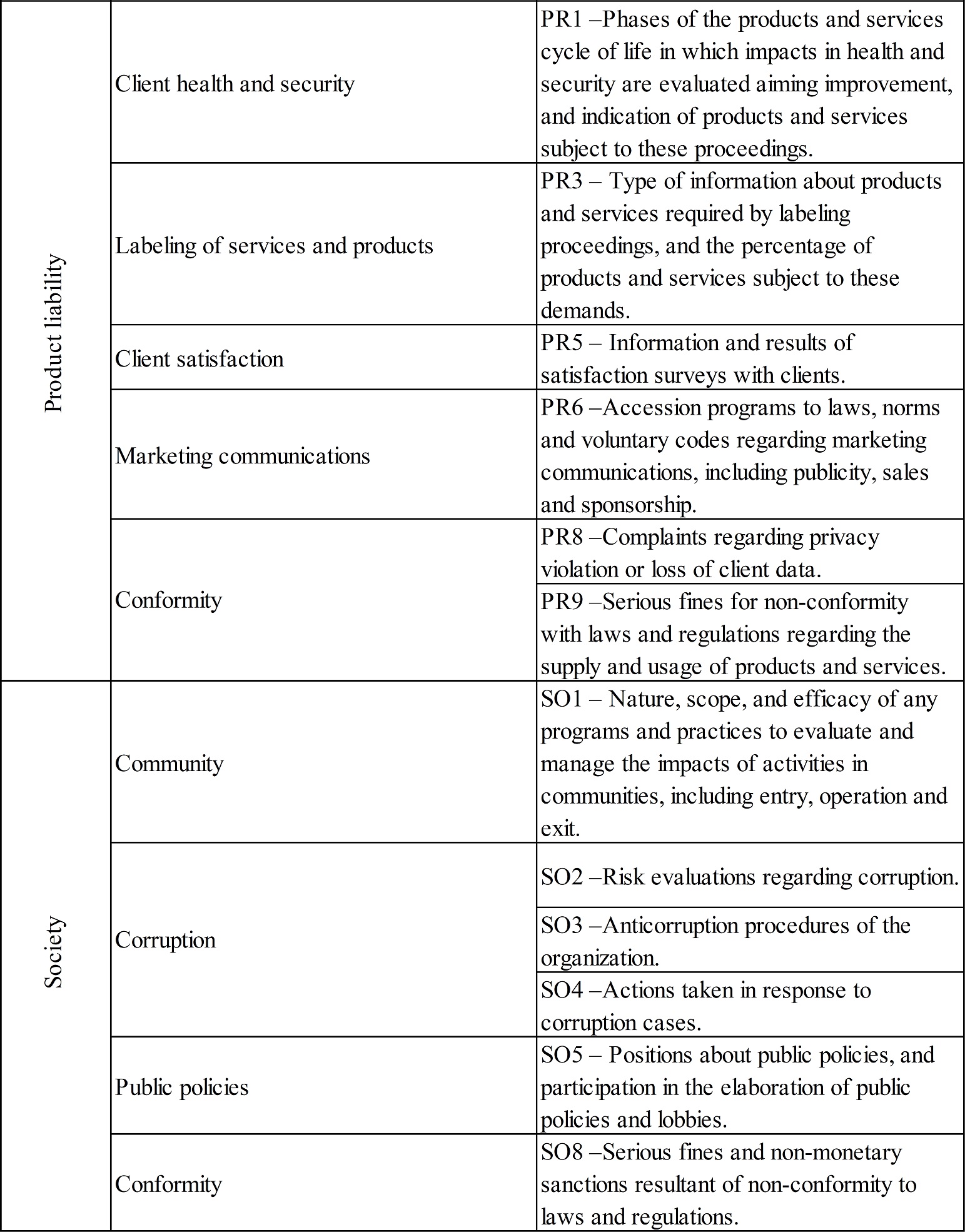

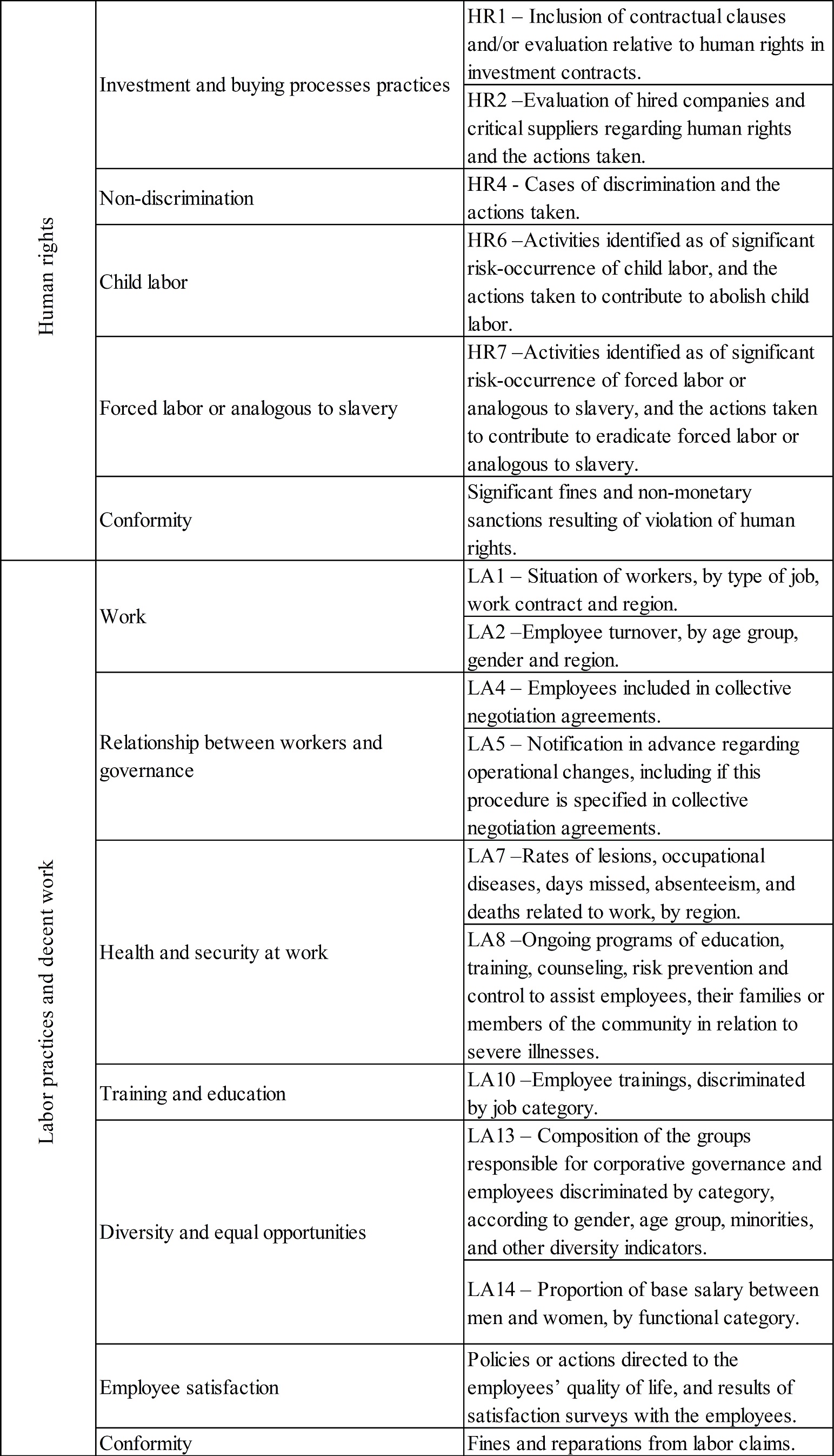

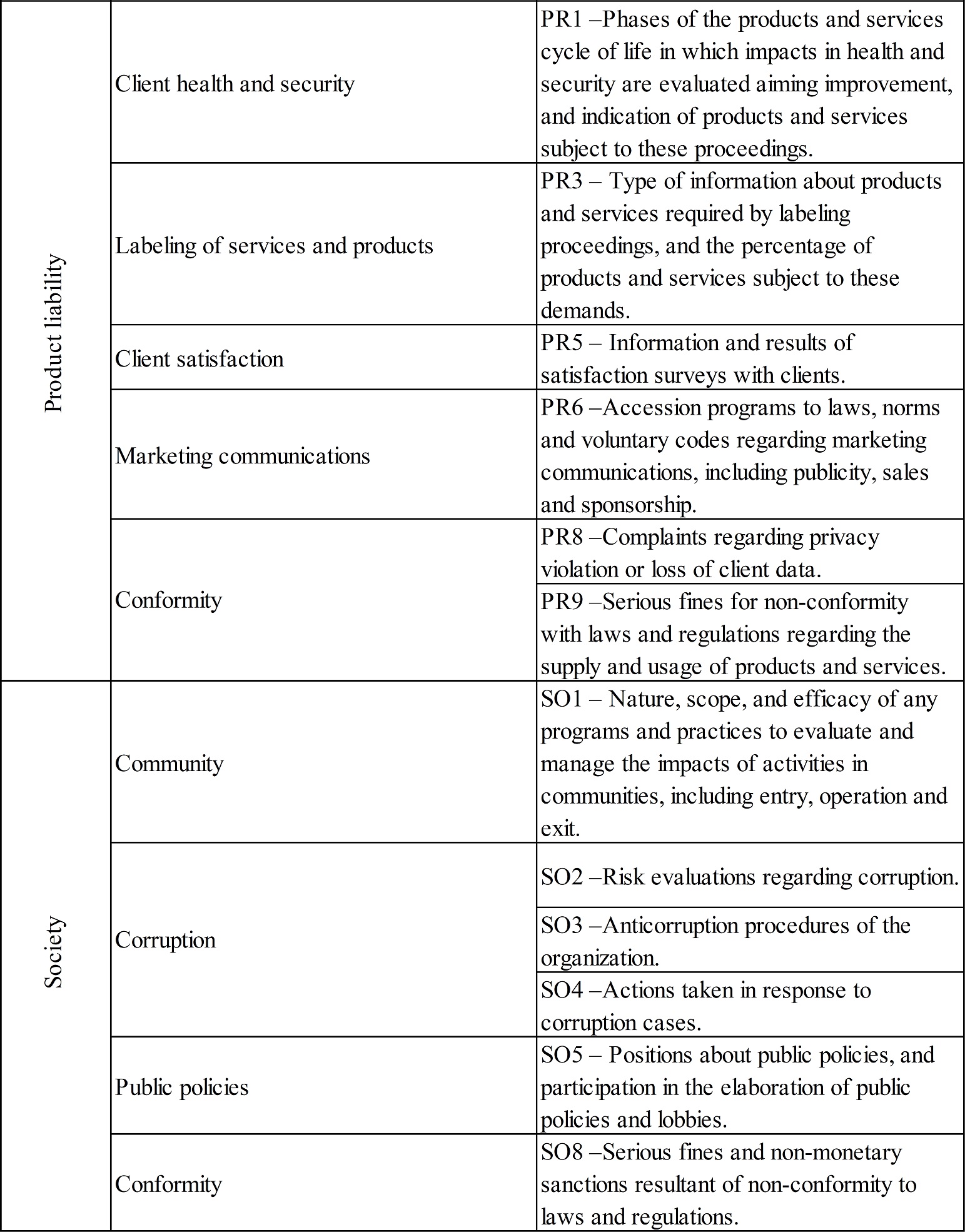

Appendix A

Essential CSR indicators

Source: adapted from the GRI Sustainability

Report Guidelines (2006)

(cont.)

Source: adapted from the GRI Sustainability

Report Guidelines (2006)

(cont.)

Source: adapted from the GRI Sustainability

Report Guidelines (2006)

Author notes

a Corresponding author. . E-mails: beneditocosta50@gmail.com

Additional information

Para

citar este artículo: Costa, B. M. N. & Lima, V. (2017). Comprehensiveness

of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports of Brazilian Companies: An Analysis of

its Evolution and Determinants. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 18(45). https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cc18-45.ccsr