Introduction

Furtado & Rozeff (1987), Weisbach (1988), Bonnier & Bruner (1989), Salas (2010) consider that the death or removal of a prominent executive does not adversely affect the value of an organization. However Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan & Newman (1985) and Borokhovich, Brunarski, Donahue & Harman (2006) show evidence that such events cause devaluation of shares.

Steve Paul Jobs was eccentric and arrogant, evidenced difficulty with social interaction and little ability to express his own emotional state. He sometimes exhibited socially unacceptable behavior and some researchers think that he had Asperger’s syndrome. Despite this, he helped create Apple and revolutionize the portable device industry, with devices like iPod, iPhone and the iPad. In 2011, Forbes Magazine ranked him as 110th among the richest men in the world, with a fortune estimated at $8.3 billion.

Extremely creative, Steve Jobs turned Apple into a multibillion-dollar company. One of his last public appearances took place in March 2011 in the iPad 2 announcement. His list of main achievements includes the personal computers Lisa, Apple II and Macintosh, films with Pixar, songs on iTunes, mobile phones like the iPhone and also the iPad. The latter was considered a lifeline for the publishing industry. Although Apple is generally recognized as a producer of computers, two-thirds of its revenue come from the distribution of music and mobile devices. In May 2011 Apple surpassed Microsoft’s revenue, and its shares rose 80% that year. It should also be mentioned that most of Steve Jobs’ fortune was represented by $4.4 billion invested in Disney World Company shares.

Steve Jobs was considered the most influential ceo on the planet with regard to technology and innovation. The series of Apple’s spectacular successes and turnovers under his command sounded like a guarantee of its unique ability to lead the company along a path of secure prosperity. So the whole period from 2003 to 2011 was characterized by intense speculation about his health, with possible effects on the price of Apple stock. It is well known that the market value of certain companies strongly depends on the presence of certain CEOs as they represent a critical element in merger and acquisition negotiations.

The management of intangible assets, especially human capital, represents a paradigm shift about the value of corporations and their ability to generate future results. Currently, the skills and abilities acquired by humans through knowledge and experience are recognized as contributing decisively to the performance of organizations (Becker, 1962). Unlike the paradigm of industrial society, in the era of knowledge human capital has become an essential element for organizations to the point that its inefficient management can lead companies to bankruptcy (Stewart, 1997).

According to Brooking (1997), human capital has become so relevant for organizations that the presence of highly competent individuals is a necessary condition for achieving positive results in fiercely competitive environments. Thus, the human being is transformed in reference to the company, so that most of them have a growth trajectory associated with the image of top executives (Perryman, Butler, Martin & Ferris, 2010); so much so that the trajectory of companies rich in intellectual capital that begin to lose such capital has particularly interested several researchers in the financial area (Borokhovich et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 1985; Salas, 2010).

Normally, negative effects should manifest when a ceo leaves an organization (Warner, Watts, & Wruck, 1988). However, this phenomenon is not found unanimously in the literature. Furtado & Rozeff (1987), Weisbach (1988), Murphy & Zimmerman (1993) show that the departure of the chief executive may be favorable to the company, especially if this ceo has managed inefficiently. If this is not the case, it may cause a negative effect on share value. Bonnier & Bruner (1989) also consider that speculation about the possible replacement of the ceo by a recognized professional is able to substantially increase the value of the company’s securities.

However, the departure of managers may also be associated with uncontrollable factors such as health problems and death. Studies have not converged on a single explanation of the market reaction in this case (Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan, & Newman, 1985; Etebari, Horrigan & Landwehr, 1985; Salas, 2010).

Etebari, Horrigan & Landwehr (1985) mention that the death of top executives tends to negatively the value of companies’ securities. Johnson et al. (1985) point out that the unexpected death of executives is more significant when it involves the company’s founders and professionals responsible for making major decisions. Borokhovich et al. (2006) indicate that when the board of directors is formed mostly by external members, the lack of a chief executive tends to have a lesser effect. Moreover, Salas (2010) states that the death of executives does not always reflect negatively in the market. The death of professionals with more than 10 years in office or who had negative returns in recent years tends to reflect positively in the market. Additionally, the death of executives contrary to the corporate restructuring process tends to reflect positively in the value of shares.

Noticeably, the literature on the relationship between the presence of prominent executives and the value of company stock is heterogeneous and divergent. Thus, this article aims to reinforce this discussion by means of the analysis of the effects of the news about the health of Steve Jobs on the value of Apple’s stocks.

The analysis focuses on a recent 9-year period in which the chief executive of the most successful company in the world of technology got involved in a difficult struggle for life and all the news and speculation around the issue were broadcast. It is therefore a unique story, full of valuable material for the analysis of impacts on the value of the company. This analysis is relevant to academia, market analysts and corporate finance professionals.

The evidence found in this article may be firsthand in that, besides showing negative market reactions to the news, speculation and rumors about the health of Steve Jobs, it also shows that the market agents gradually incorporated the anticipated effects of future events in their decisions.

This article comprises five sections besides this introduction: human capital in organizations, an observation on the efficiency of markets, methodological notes, discussion of results and conclusion.

Human capital in organizations

Since the 1960’s economic and social changes have significantly altered the structure and values of society. For Drucker (1992), in this new society traditional production factors have become less important as knowledge acquired the status of the most important economic resource, and became the main competitive advantage among companies. Several studies describe this period as a transition from an industrial society to a knowledge society (Antunes & Martins, 2007; Antunes, 2000; Edvinsson & Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1997; Stewart, 1997).

In this new society, information and knowledge outweigh physical and financial capital. That is, information and knowledge became the key competitive advantage and primary wealth of organizations (Crawford, 1991). Unlike goods and services, knowledge does not disappear when consumed in production and then sold. A tangible asset depreciates with use, but knowledge, in contrast, grows and gains value (Sveiby, 1997).

For Nonaka & Takeuchi (1996), knowledge has two forms: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge is formal and systematic, comprises the numbers and words easily communicated and shared in the form of raw data, scientific formulas, codified procedures or universal principles. Tacit knowledge is rooted in action and individual commitment in a particular context (Nonaka, 1991) covering skills and techniques developed through acquired know-how, added to perceptions, beliefs and values that reflect the perceived image of reality. This shapes the way one deals with the world. Tacit knowledge is acquired through education, academic research and concept of the world that are directly associated with the actions and experiences of individuals (Antunes & Martins, 2007). These actions and experiences are components that obstruct the externalization of tacit knowledge, making it difficult to transmit and share. Furthermore, tacit knowledge developed and applied in a company can hardly be applied to another with the same results (Antunes, 2000).

Steve Jobs has become famous for his revolutionary personality and his ability to transform his business into one of the largest and most profitable (Kahney, 2008). However, the model he developed and applied to Apple, based on his tacit knowledge, could hardly be developed and applied to another company with similar results. This highlights one of the main characteristics of the knowledge economy and human capital (Crawford, 1991).

Human capital refers to a set of productive powers of human beings, comprising knowledge, skills and aptitudes that produce economic results (Baptiste, 2001; Becker, 1962). The Human Capital Theory is founded on the idea that the acquisition of knowledge and skills adds value by improving the productivity and efficiency of people and reflecting on the performance of organizations (Cunha, Cornachione Junior, & Martins, 2010). In brief, it is observed that at the present time, knowledge is an organizations’ main competitive factor, that is, organizational intelligence is no longer a secondary factor and has taken the lead role. Companies that do not properly manage knowledge, jeopardize their very survival (Stewart, 1997).

Although human capital is of major importance to organizations, this expression only appeared in 1961, in the famous article by Theodore W. Schultz entitled Investment in Human Capital. In this article, the author considers education as a category of investment in human beings, giving support to the idea that acquired knowledge is capital. Soon after, Gary S. Becker (1962) published the celebrated article entitled Investment in Human Capital: a theoretical analysis, which expanded the concept through the development of a theory of investment in human capital, with emphasis on empirical implications. Becker investigated the ability of certain activities to exert influence on people’s future income and wellbeing. He aimed to fill gaps in the explanation of the phenomena related to human capital (Cunha et al., 2010).

According to Hsu and Wang (2012) human capital represents an added value to the activity of an organization. Companies that have a skilled human capital are more inclined to perform better in the market in which they operate. Even though the concept of human capital was originally associated with the economic value of education (Schultz, 1961), it also relates to the logic that determines the way people’s skills, competencies and experiences exert influence on the economic value of organizations (Huselid & Becker, 1997). The development of human capital in organizations is mainly associated with the figure of a leader. The leader is the person who makes a difference to the organization due to its ability to materialize the available knowledge, converting it into wealth and income for the company (Antunes, 2000). Brooking (1996) points out that the actions of some leaders are positively associated with high returns achieved by organizations. Thus, companies would be subject to negative impacts on their results and their market values if such professionals depart.

The previous considerations show that events related to the work of outstanding executives tend to interfere in investor perception, therefore influencing the stock price. However, this does not occur within a well-defined time frame and in a crystalline and easily measurable way. The identification and measurement of events may be blurred by the occurrence of simultaneous events, and effects on stock prices depend on the market efficiency level.

The hypothesis of market

efficiency

Through the capital market, companies negotiate their shares, enable the raising of funds and provide liquidity to investors. The suitable functioning of the capital market depends on information, because all agents need to be informed to properly make decisions.

The hypothesis of market efficiency reflects the importance of information to the capital market (Copeland & Weston, 1992). This hypothesis is based on the presupposition that bond prices instantly reflect all relevant information available to the market (Camargos & Barbosa, 2006). The discussion about the efficiency of markets gained prominence after the study of Kendall & Hill (1953), according to which the variations in stock prices would be completely random, with no regularity, as cycles or seasonality (Ceretta & Costa Junior, 2001).

The hypothesis of efficient markets is based on the following ideal conditions: no transaction costs in securities trading, availability of all information at no charge to all participants, and general agreement of expectations regarding the effect of information on stock prices (E. F. Fama, 1970). In practical terms, a market is considered efficient if the available information reflects on prices of securities immediately or after a minimum interval from the disclosure (Hendriksen & Breda, 1992).

Fama (1970) proposes three forms of efficiency: weak, semi-strong and strong. In weak form, the price of the securities completely reflects the information implicit in the historical sequence of prices themselves. On the other hand, in strong form, prices fully reflect both inside information and all publicly available information. In the semi-strong form, bond prices incorporate all information available to the public, including current and past prices; however, prices do not reflect the private information. In other words, in a semi-strong efficiency market, bond prices behave as if all agents would make decisions according to publicly available information. For semi-strong efficiency markets, Fama (1991) indicates the event study methodology to evaluate price adjustments of securities at the information publication dates. The US bond market is generally attributed to semi-strong efficiency (Hendriksen & Breda, 1992).

Although the first event study was developed in the mid-1930’s (Dolley, 1933), these studies did not achieve popularity and sophistication until the 1960’s (Ball & Brown, 1968; Fama, Fisher, Jensen, & Roll, 1969). Since then, several event studies (Borokhovich, Brunarski, Donahue & Harman, 2006; Johnson, Magee, Nagarajan & Newman, 1985; Salas, 2010) proved to be a powerful tool to capture the impact of specific events on stock prices (BINDER, 1998).

Johnson et al. (1985) conducted a study on the American stock market, based on 53 announcements of executives’ deaths from 1971 to 1982. The results indicate that abnormalities in the stock price are more significant when referring to the companies’ founders and executives responsible for making major decisions. Borokhovich et al. (2006) analyzed the reaction of the US stock market on a sample of 161 executives’ death notices from 1978 to 2000. The results indicate that while there is a negative relationship between the death of a ceo and the price of securities, the market reaction is attenuated when the board is comprised mainly of independent professionals. This suggests that the presence of external board directors minimizes the effects caused by the loss of a senior executive.

Salas (2010) investigated the stock price reaction of US companies due to the unexpected death of their CEOs. With a sample of 195 observations arising from the period 1972-2008, the results suggest that not always does the death of an important executive reflect negatively on the market. The findings indicate that when the ceo holds the position for more than 10 years and the returns of the last three years have been negative, the death tends to present positive impact on the market. This is also observed when the death of chief executives occurs, contrary to corporate restructuring.

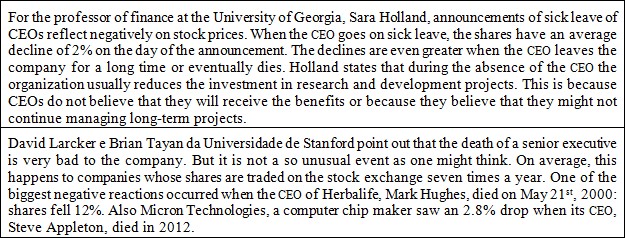

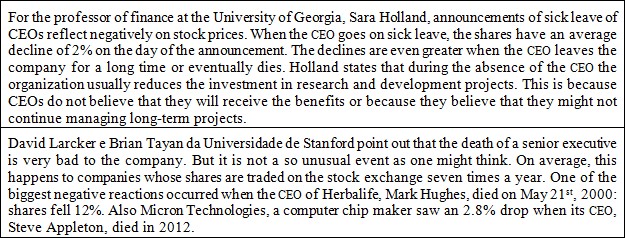

Furthermore, Krantz (2013) highlights some studies on the relationship between news about the health of key executives and stock prices, as shown in table 1.

Table 1

Some additional studies on the impact of health status

of CEOs

Source: Adapted from Krantz

(2013).

It is noted that

studies on the relationship of senior executives’ health problems and the

return of the shares in the US market do not converge. While some authors argue

that there is a significantly negative relationship between the two variables (Borokhovich, et al., 2006; Johnson, et al., 1985),

others point out situations in which the death of the chief executive is well

received by the market (Salas, 2010).

This article is intended to participate in this discussion adopting the

perspective of the Human Capital Theory to assess the effects of the announcements

relating to the health of Steve Jobs on the price of Apple stock.

Methodological notes

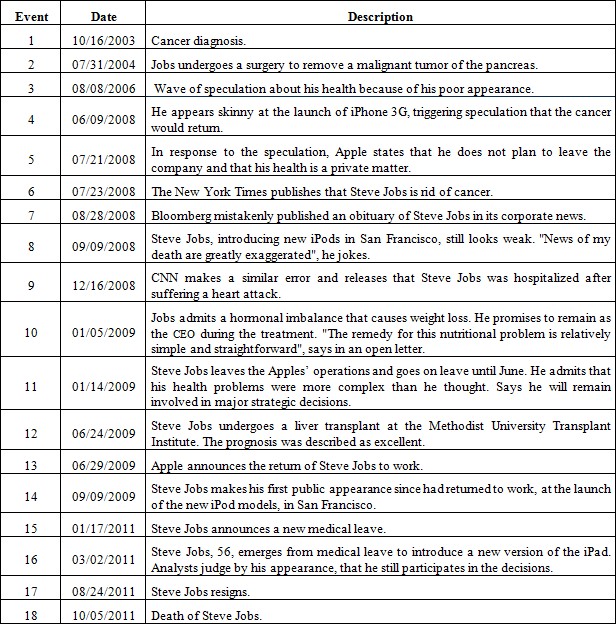

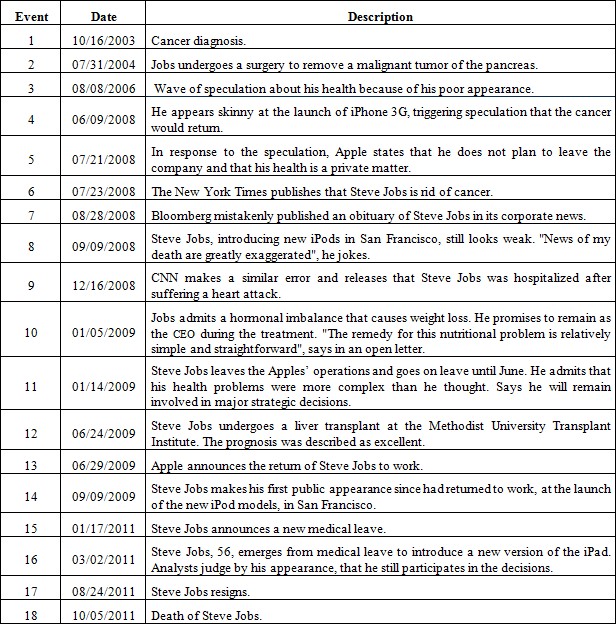

The events were defined as the date of publication of news about the health of Steve Jobs. Data was collected from specialized websites: The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, cnn, Reuters, and Bloomberg. This resulted in 18 potentially relevant events as shown in table 2.

Table 2

Significant events relating to the health of Steve Jobs

Source: adapted from The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, CNN, Reuters

and Bloomberg.

The prices of Apple’s shares and the Dow Jones Index for the period of 03 January 2003 to 2 December 2011 totaled 2,241 observations. The S&P 500, the NASDAQ Index and the NASDAQ-100 Index showed equivalent results to those obtained with the Dow Jones Index.

Results and analysis

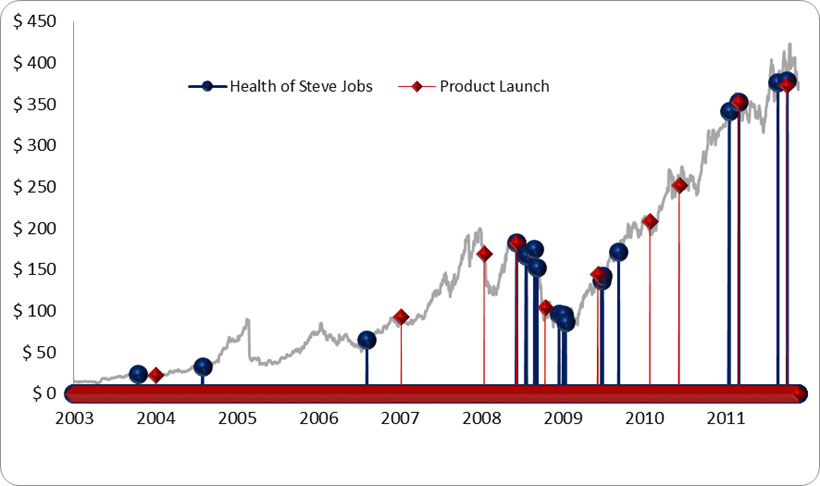

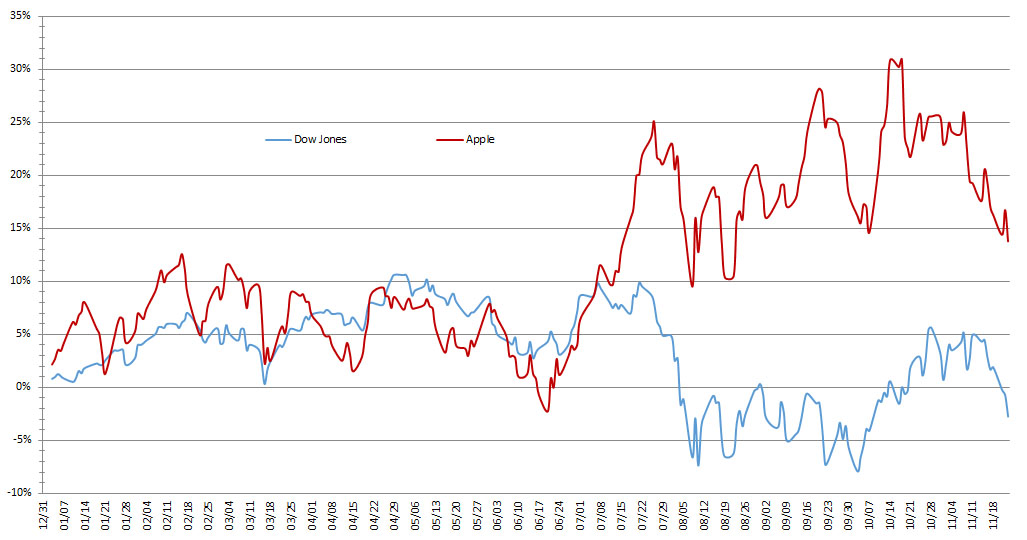

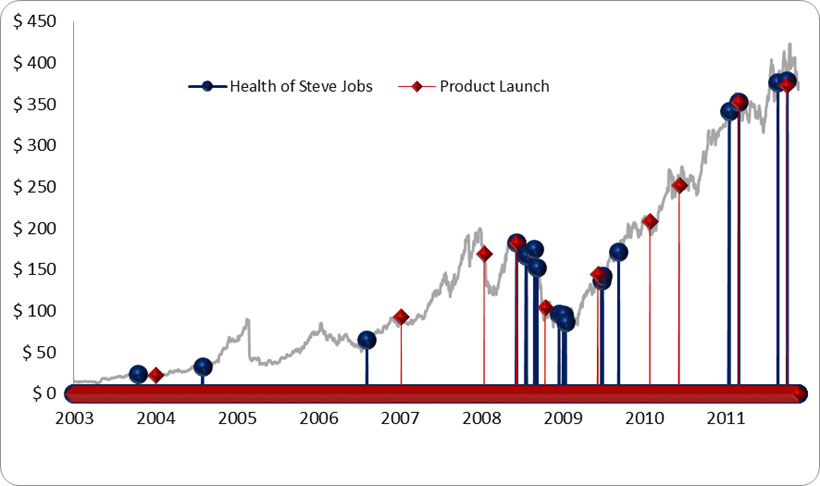

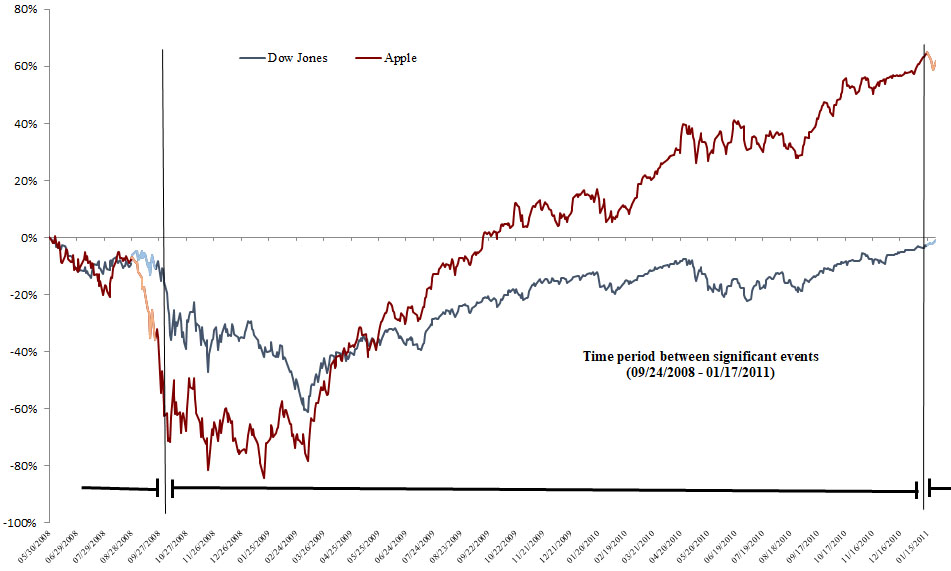

Chart 1 illustrates the significant appreciation of Apple from 2003 to 2011. One can also see the distribution in time of the 18 events related to the health of Steve Jobs and the 10 product launches made in that period.

Chart 1

Events related to the health of Steve Jobs and the product launches from 2003 to 2011

Chart 1

Events related to the health of Steve Jobs and the product launches from 2003 to 2011

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016).

In table 3, the major Apple product launches during the period are identified.

The first three events relating to the health of Steve Jobs, widely reported in specialized news, do not emerge as statistically significant. These events do appear as forces able to substantially change the prices of Apple stocks. Although the news involving the health of the ceo had begun to circulate in specialized areas at the end of 2003, only in June 2008 was an event with a significant effect on the market detected.

Some health-related events of Steve Jobs occurred simultaneously or nearly simultaneously with new product launches. It is even possible that there was concern with mitigating the negative impacts of news and speculation through the launch of new products. The possibility that the new product launches have partially or totally eclipsed the effects of the news and speculation about the health of Steve Jobs calles for particular caution in analyzing the events.

Chart 1 shows that in the period 2003 to 2007 the two product launches preceed periods of valuation of Apple’s stock. This chart also shows that the three events relating to the health of Steve Jobs in that period were not followed by devaluation of the shares. This clearly indicates that analysts and investors, at that time, regarded the news as representative of transitory situations, without more serious consequences.

On June 9, 2008, the media highlighted the ashen face of Steve Jobs at the launch of iPhone 3G. The weak aspect of the executive triggered speculation about his health. According to the Los Angeles Times (2008), the comments at the conference addressed more the 53year old ceo’s appearance than the launch of the new product. As a result, the US market showed a negative reaction to the company’s stocks in the immediate period and caused cumulative loss of around 8% within 51 days. This suggests that the speculation about the appearance of Steve Jobs gained such prominence in the media as to overcome the effects of the new product launch.

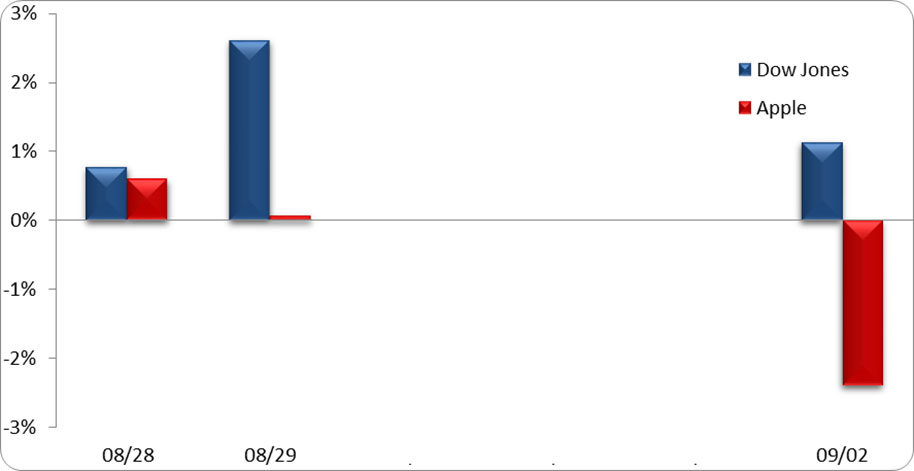

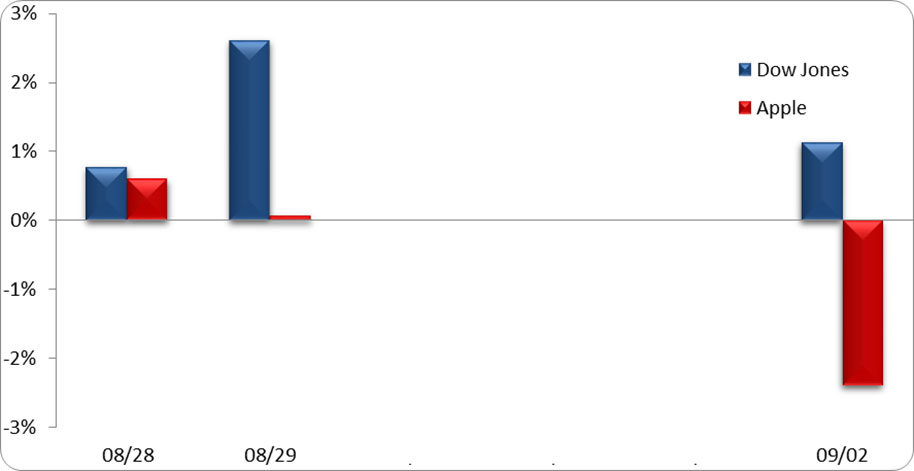

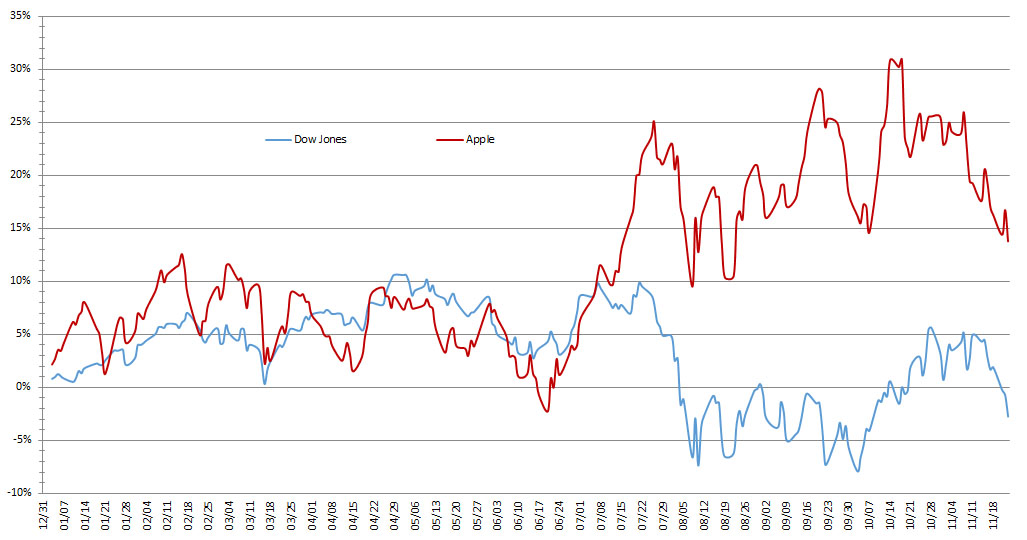

On Thursday, August 28, 2008, the renowned website news of Bloomberg mistakenly published the death of Steve Jobs in a 2,500 word text. Although the error was promptly corrected, the news was reflected negatively and strongly in the stock price. On the same day, although the Dow Jones Index presented elevation of about 2%, Apple shares fell. On Friday, August 29, the Dow Jones Index showed a slight upward movement while Apple shares fell about 1%. Monday, September 1, was a national holiday commemorating Labor Day. On Tuesday, September 2, Apple’s stock showed a cumulative loss of around 2%, a completely different pattern in comparison to the stock market. Chart 2 shows these impacts.

Chart 2

Accumulated variations of Apple stock returns and the Dow Jones

Chart 2

Accumulated variations of Apple stock returns and the Dow Jones

Source: Prepared by the authors (2016).

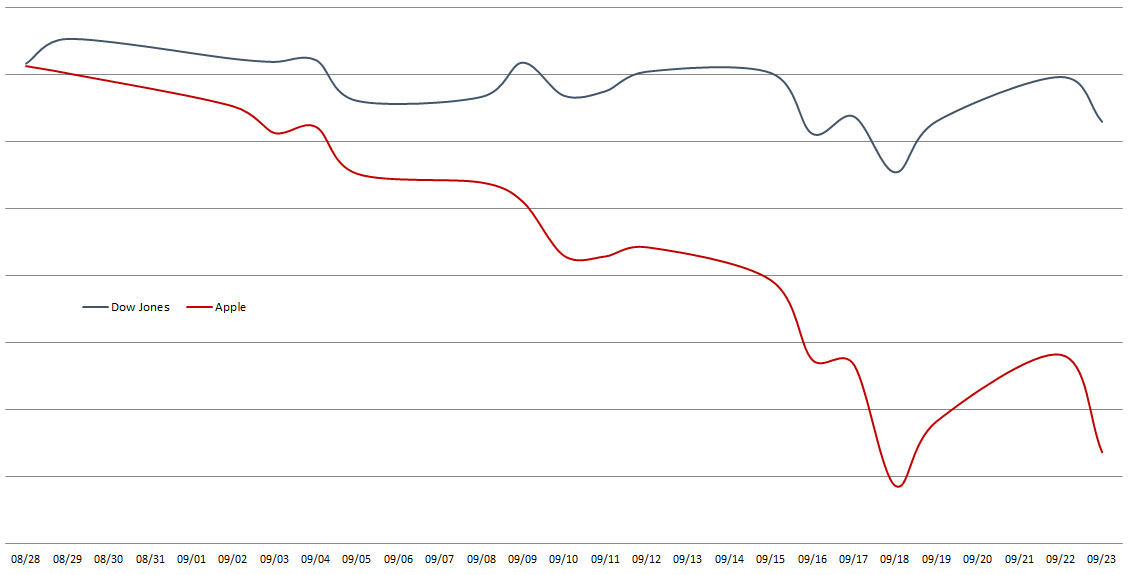

Only 11 days later, during the presentation of new products in San Francisco (September 9), Steve Jobs emphasized that the news about his health was greatly exaggerated. This speech did not convince the market which, due to his weakened countenance, reacted strongly in the opposite direction to the optimism of the executive. This time, the impact of the launch of new products was far offset by the negative effect of speculation and rumors about his health and, in just 14 days, Apple shares accumulated a loss of more than 27%. At this time, the association between the perception of the health of the ceo and the stock value seems unquestionable and shows that the market reacted promptly and significantly.

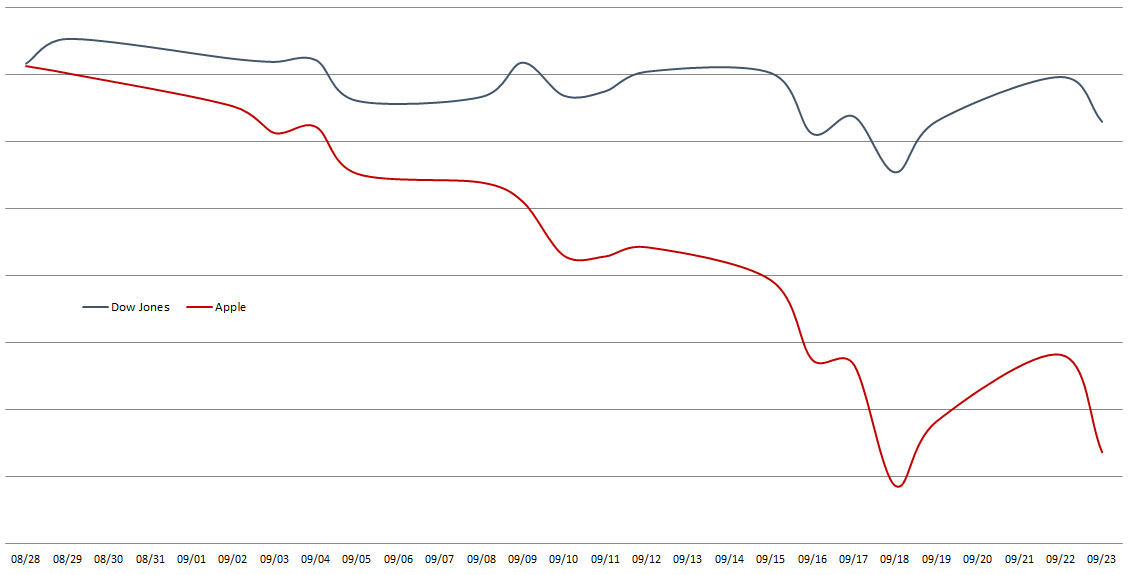

From the statistical point of view, the events of August 28 and September 9, 2008 can be regarded as a single event, as they are spaced by a single trading session. Chart 3 shows the cumulative changes in the Dow Jones and Apple’s stock returns over the period of August 28 to September 23, 2008.

Chart 3

Accumulated variations for the period from 28 August to 23 September, 2008

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016)

Chart 3

Accumulated variations for the period from 28 August to 23 September, 2008

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016)

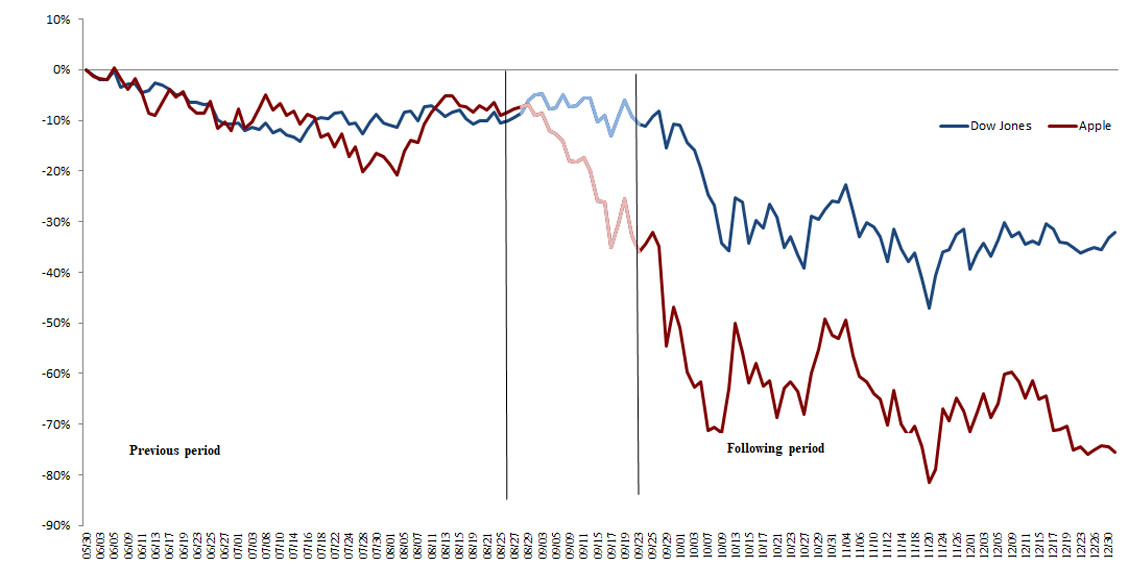

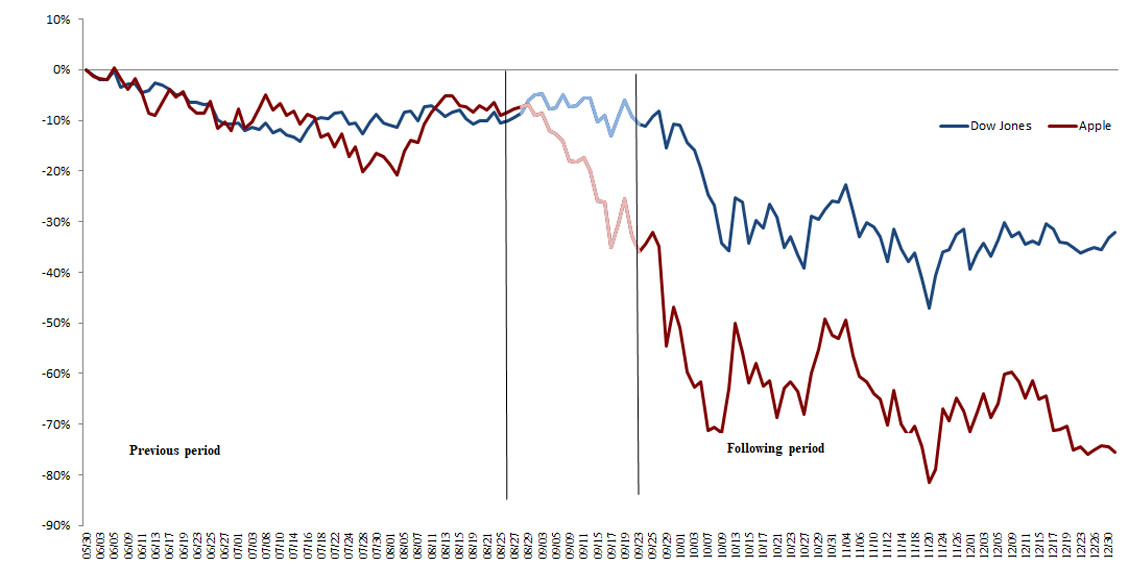

August and September 2008 events occur in the acute phase of the financial crisis. At that time the Dow Jones Index presented a persistent downward trend, but Apple shares accumulated significantly greater losses: the Dow Jones showed a cumulative loss of 4% from August 28 to September 23, while Apple shares fell 28%. There is still something important to highlight about the period of foreboding starting with the incorrect announcement of Steve Jobs’ death. As shown in Chart 4, which covers the entire second half of 2008, Apple’s stock returns show a singular behavior during the financial crisis of 2008.

Chart 4

Accumlated effects during the Financial Crisis of 2008

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016).

Chart 4

Accumlated effects during the Financial Crisis of 2008

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016).

Apple’s stock returns were accompanying the Dow Jones index until the end of August 2008, and then shifted out of the Index and began to accumulate much larger losses. The accumulated losses of Apple stock in the second half of 2008 reached 68%, while the Dow Jones index in the same period fell by only 27%. The mistaken announcement of Steve Jobs death on August 28 and his appearance showing very clear signs of physical weakness, on September 9, were decisive factors in influencing the value of Apple’s stock. From these events, it fell sharply and persistently from these events for all the second half of 2008.

Specifically, Apple’s stock show three stages during the second half of 2008: 1) by the end of August, they oscillate around the Dow Jones; 2) from early September to late October, they accumulate substantially higher losses than the Index; and 3) in the months of November and December, instead of recovery, the continue to show returns below market. There is, therefore, clear indication that the events of late August and early September 2008 have definitely changed the perception of investors in relation to the continuity of the ceo, head of Apple.

No event related to the health of Steve Jobs was shown to be able to significantly change the behavior or expectations of the market. Not even in a long period of more than two years following the events of late August and early September 2008. The market appears to show that nothing could change the perception formed and fixed from those events.

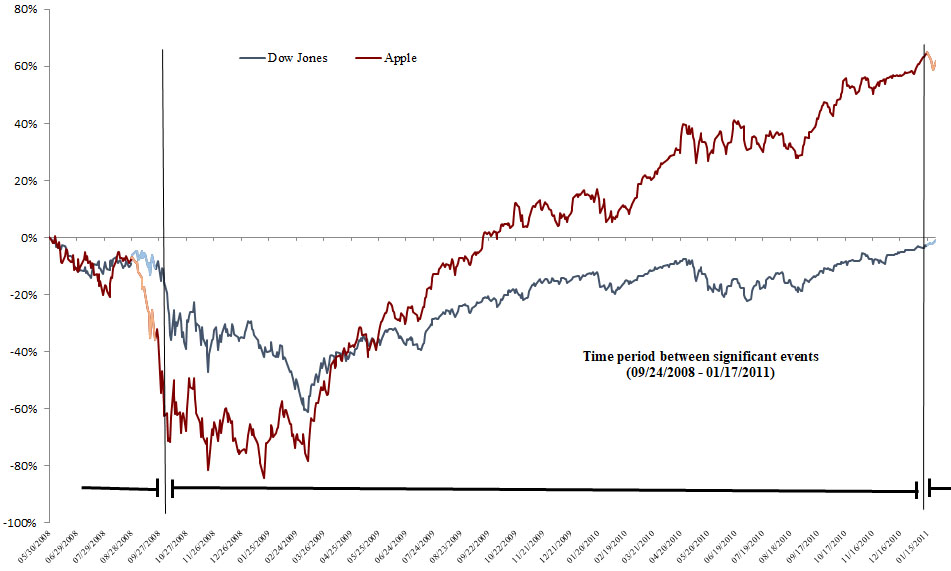

Chart 5 covers the whole period from September 2008 to January 2011. This chart reveals that Apple’s stock returns showed two distinct phases in 2009. In a first sub-period, analysts and investors slowly conclude the process of incorporating the key events of August and September 2008 in their expectations. As a consequence, Apple’s cumulative stock return continues to fall more than the cumulative return of the Dow Jones Index. This is a characteristic, semi-strong efficiency market behavior. In a second phase, Apple’s shares recovered, and just at the end of the year presented positive, cumulative return, far superior to the Dow Jones, which remained negative.

Chart 5

Time period between the most significant events

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016).

Chart 5

Time period between the most significant events

Source:

Prepared by the authors (2016).

This recovery was wisely exploited by Apple who made two outstanding releases in early 2010: the iPad on January 27; and the iPhone 4 on June 7. Apple knew how to take advantage of the favorable winds and consolidated a new period of great prosperity that would result, in early 2011, in a cumulative return of Apple’s shares equal to 77%, not at all comparable to the cumulative returns of the Dow Jones Index, which reached only 3%.

A particular issue is essential to the analysis of this trajectory of intense, continued growth. How to explain the spectacular resumption of Apple’s stock appreciation in mid-2009? Would it be due to the official return of Steve Jobs to the company in June 2009? Or was it because the market started to perceive Apple as an entity independent of the renowned ceo? Or were these two factors at work at the same time?

Chart 6 shows the cumulative return of the Apple’s shares and the return of the Dow Jones Index in 2011 and helps to answer these questions. On January 17, 2011, Steve Jobs announced a new medical leave and on March 2 reappeared to present a new version of the iPad. One can find out by means of Chart 6 that these events, although statistically significant, did not substantially change Apple’s stock cumulative returns in comparison to the Dow Jones Index. Then, on August 24, Steve Jobs resigns definitely from the presidency of Apple and on October 5 passes away. Again, though statistically these events prove significant against the Dow Jones, there are no signs that the market has reacted negatively on a broader scale.

Chart 6

Cumulative Return of the Apple's shares and Dow Jones Index in 2011

Source: Prepared

by the authors (2016).

Chart 6

Cumulative Return of the Apple's shares and Dow Jones Index in 2011

Source: Prepared

by the authors (2016).

The 2011 events indicate the market already perceived the personality of Steve Jobs and Apple as predominantly divorced. Certainly this market perception had been growing and consolidating over time, since the crucial period of August and September 2008. The relevant question, in this regard, is whether this process of untying would not be well under way and to some extent consolidated in mid-2009, when the company returned to present value growth.

Eloquent proof of this hypothesis of increasing disengagement of the Apple’s ceo is found in the June 24, 2009 event, when Steve Jobs underwent liver transplant surgery. Obviously, this event had great potential to impact the market, but shares continued booming. At that time the vast majority of agents already recognized Apple as an entity independent from the renowned executive.

Thus, the official return of Steve Jobs to the company command does not seem to have been the determining factor. Instead, the spectacular growth would have as a main cause the fact that Apple demonstrated the ability to keep up with highly valued innovations in spite of illness and the likely permanent absence of Steve Jobs.

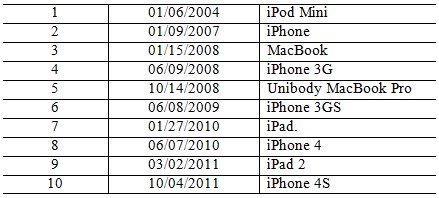

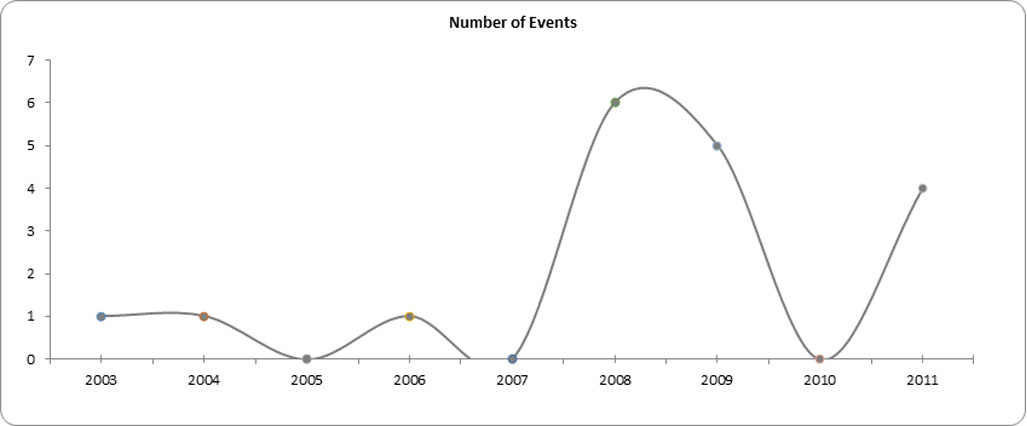

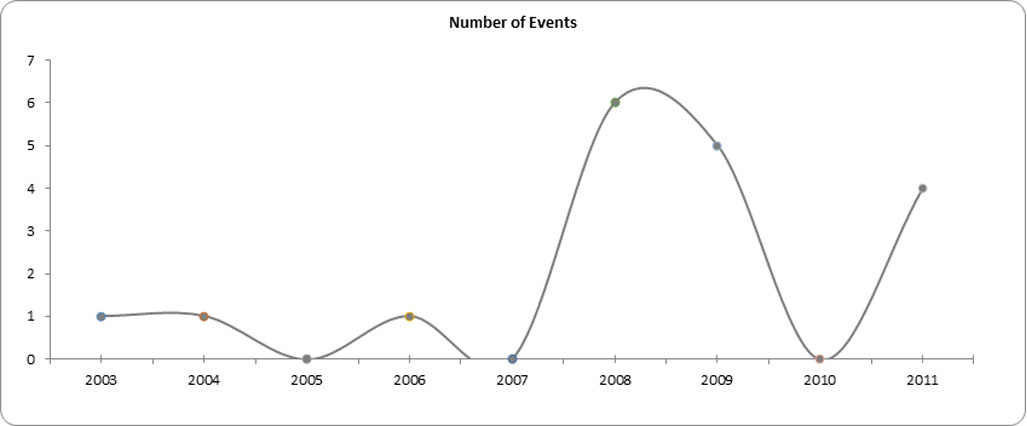

The specialized media played a supporting role of some importance in the period of rapid growth in the prices of Apple stock, as shown in Chart 7. In 2008, six events related to the health of Steve Jobs were widely reported; in 2009, five; and in 2010, none at all. Having officially resumed its activities at Apple on June 29, 2009, Steve Jobs only turns away on January 17, 2011. Throughout this period most of the news about Apple did not point out the state of his health and went on to point out positive aspects of the company and its products.

Chart 7

Number of events relating to the health of Steve Jobs, 2003-2011

Source: prepared by the authors (2016).

Chart 7

Number of events relating to the health of Steve Jobs, 2003-2011

Source: prepared by the authors (2016).

In early 2011, two years and four months after the decisive events of August and September 2008, Steve Jobs announced a new medical leave, giving way to Tim Cook. Although he claimed publicly that he was still involved in the process of business decision-making, this was not enough to convince the market that outlined a pale, negative reaction.

On March 2, 2011, Steve Jobs emerged from medical leave to introduce a new version of the iPad. His good appearance was considered by analysts and investors as a safe indication that he still participated in the making of business decisions. However, the positive news about the health of the ceo, along with the launch of a new product were not enough to make the company’s stock rise, embittering a negative cumulative return of 2% in the period.

Later in August 2011, weakened by cancer, Steve Jobs decides to step down as president of Apple. In contrast to what would be expected, the market shows a small positive reaction to this event. This suggests that his resignation was not only expected but that, on average, was perceived as favorable. According to analysts, the departure of Steve Jobs was a matter of "when." That is, agents had already incorporated this fact into their expectations. Furthermore, there remains an indication that some investors considered that the departure of Steve Jobs increased the company’s value.

Since the beginning of 2011, the ceo was on medical leave due to undisclosed reasons. This certainly helped to make present the events that had occurred since 2003, such as the diagnosis of cancer in that year and the liver transplant in 2009. These facts certainly presented clear depictions indicating that his presence as head of Apple was definitely ruined. It seems certain that the market would have acquired a widespread perception that the genius of Steve Jobs was not able to overwhelm the limitations brought about by his illness.

Steve Jobs died on October 5, 2011, almost two months after his resignation. Although the news was reflected negatively on the market, the change was relatively small, well below the impact of news about his health when he was still head of Apple. This supports the hypothesis that the effects of his definitive removal were already reflected in share prices as expectations.

As the US stock market presents a semi-strong efficiency, the reactions and adjustments occur predominantly on the basis of the available information, provided especially by the specialized press. Furthermore, the reaction continues for a certain period, to the extent that the agents are informed and adjust their positions. Analysts and investors make the events reflect in stock prices as they go on incorporating the facts and expectations to their assessments.

The analysis developed here shows that the first negative news about the health of Steve Jobs had a cushioned effect. This is due to the possibility that it might indicate minor and transient situations. This state of alert would be transformed into a very unfavorable perception with the August and September 2008 events. Then, from that time the market began to respond more moderately to the news and increasingly realize the possibilities of the company’s profits independently of the health of Steve Jobs.

Conclusion

The possibility of the effects of news about Steve Jobs health being mitigated or eclipsed by product launches has been carefully considered and, as a result, findings are mostly free of these effects.

Steve Jobs fell ill when he was at full capacity and his talent was making Apple a very profitable and very promising company. He was not, therefore, an executive who had shown poor results for a long period of time, whose removal would be well received by the market. The present results are in line with Etebari, Horrigan, Landwehr (1985) and Johnson et al. (1985) with regard to a negative relationship found between the stock price and the news and speculation about the health of Steve Jobs. Also, the results disagree with Salas (2010) about the existence of a positive market reaction when the executive was in office for more than 10 years.

The analysis shows three distinct phases of the effects of the news and speculation about the health of the Apple’s ceo. Initially, the market considered that the news was temporary, without significant long-term effects. Then, in 2008, the news and speculation resonated heavily on Apple shares and brought about a definite change in the perception of analysts and investors. So, adjustments were made in a relatively short period. However, in a third stage, thanks to the strength that the company continued to demonstrate, the market began to perceive it as increasingly independent of the personality of Steve Jobs. The result was a vigorous growth trajectory of Apple’s value from mid-2009. As demonstrated, these findings are consistent with the characterization of the US stock market as a semi-strong efficiency one.

The impact of specialized news becomes evident in the gaffe by Bloomberg News on their website. The false news about the death of Steve Jobs provoked a strong and immediate reflex, causing Apple shares to drop considerably. Furthermore, this event plays a central role in changing market behavior in relation to the Apple’s stocks, as demonstrated.

Results presented here are mainly aligned with authors that link negative effects to the removal of the chief executive, but the wealth of detail and the long period in the analyzed case, allow identifying an initial phase of certain inertia due to underestimation of the effects. This is an intermediate phase of substantial changes in behavior and expectations and, again, a phase of indifference because the expectations had already incorporated previous decisive events.

References

Antunes, M., & Martins, E. (2007). Gerenciando o capital intelectual: uma proposta baseada na controladoria de grandes empresas brasileiras. REAd, 13(1), 1-22. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=401137456001

Antunes, M. (2000). Capital Intelectual. Sao Paulo: Atlas.

Ball, R., & Brown, P. (1968). An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. Journal of Accounting Research, 6(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490232

Baptiste, I. (2001). Educating lone wolves: Pedagogical implications of human capital theory. Adult Education Quarterly, 51(3), 184-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/074171360105100302

Becker, G. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. The Journal of Political Economy. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

Bonnier, K., & Bruner, R. (1989). An analysis of stock price reaction to management change in distressed firms. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 11(1), 95-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(89)90015-3

Borokhovich, K., Brunarski, K., Donahue, M., & Harman, Y. (2006). The Importance of Board Quality in the Event of a CEO Death. The Financial Review, 41(3), 307-337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.2006.00145.x

Brooking, A. (1997). Intellectual Capital: Core Assets for the Third Millennium Enterprise. Long Range Planning (vol. 30).

Bruce Johnson, W., Magee, R., Nagarajan, N., & Newman, H. (1985). An analysis of the stock price reaction to sudden executive deaths. Implications for the managerial labor market. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 7(1-3), 151-174. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(85)90034-5

Camargos, M. De, & Barbosa, F. (2006). Eficiência informacional do mercado de capitais brasileiro pós-Plano Real: um estudo de eventos dos anúncios de fusões e aquisições. Revista de Administração, São Paulo, 41(1), 43-58. https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.0148T6

Ceretta, P. & Costa Junior, N. (2001). Particularidades do mercado financeiro latino-americano. Revista de Administracao de Empresas. 41(2), 72-77. http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rae/v41n2/v41n2a08.pdf

Copeland, T. & Weston, J. (1992). Financial Theory and Corporate Policy, 3 ed. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Crawford, R. (1991). In the Era of Human Capital. New York: Harpercollins.

Cunha, J. (2007). Doutores em Ciencias Contabeis da FEA/USP: Analise sob a otica da teoria do Capital Humano. Thesis (Ph.D. in Controlling and Accounting). Universidade de Sao Paulo.

Cunha, J.Da, Cornachione Junior, E., & Martins, G. (2010). Doutores em ciências contábeis: análise sob a óptica da teoria do capital humano. Revista de Administração Contemporânea, 14(3), 532–557. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-65552010000300009

Dewatcher, P. (1997). Interaction Entre l’Essartage and l’Ecosystème Forestier. Les Peuples des Forêts Tropicales, Systèmes Traditionnels et Développement Rural en Afrique Equatoriale, Grande Amazonie and Asie du Sud-Est. Bruxelles: Civilisations.

Dolley, J. C. (1933). Characteristics and procedure of common stock split-ups. Harvard Business Review.

Drucker, P. F. (1992). The New Society of Organizations. Harvard Business Review, 70(5), 95-105. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9301105369&lang=es&site=ehost-live

Edvinsson, L., & Malone, M. (1997). Intelectual Capital. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=uP21YAsNWHcC&dq=capital+intelectual&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Etebari, A., Horrigan, J., & Landwehr, J. (1985). To be or not to be? Reaction of stock returns to sudden deaths of corporate chief executive officers. Financial Review, 20(3), 38-38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6288.1985.tb00216.x

Fama, E. (1970). Efficient capital markets-a review of theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383-417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2329297

Fama, E. (1991). Efficient Capital Markets: II. The Journal of Finance, 46(5), 1575. https://doi.org/10.2307/2328565

Fama, E., Fisher, L., Jensen, M., & Roll, R. (1969). The Adjustment of Stock Prices to New Information. International Economic Review, 10(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.2307/2525569

Furtado, E., & Rozeff, M. (1987). The wealth effects of company initiated management changes. Journal of Financial Economics, 18(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(87)90065-1

Gruber, J.

(2013). Apple’s stock price after product announcements. Daring Fireball. Oct.

04. Available at: http://daringfireball.net/2013/10/apples_stock_price_product_announcements. Access: Mar. 8, 2016.

Hendriksen, E. & Breda, M. (1992). Accounting Theory, 5 ed., Homewood, IL: Irwin.

Hsu, L. & Wang, C. (2012). Clarifying the effect of intellectual capital on performance: The mediating role of dynamic capability. British Journal of Management, 23(2), 179-205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00718.x

Huselid, M., & Becker, B. (1997). The Impact of High Performance Work Systems, Implementation Effectiveness and Alignment with Strategy on Shareholder Wealth. Academy of Management Proceedings, 1987(1), 144-148. https://doi.org/10.5465/ambpp.1997.4981101

Kahney, L. (2008). Inside Steve’s Brain. New York: Penguin.

Krantz, M. (2013). Apple heads to lows not seen since Steve Jobs died. USA Today. Access: Jan. 7, 2016, http://www.usatoday.com/story/money/markets/2013/04/18/apple-crash-steve-jobs/2094379/

Kendall, M., & Hill, A. (1953). The analysis of economic time-series-part i: Prices. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A, 116(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.2307/2980947

Murphy, K., & Zimmerman, J. (1993). Financial performance surrounding ceo turnover. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 16(1-3), 273-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(93)90014-7

Nonaka, I. (1991). The Knowledge Creating Company. Harvard Business Review, 69, 96-104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(96)81509-3

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1996). The knowledge-creating company: How Japanese companies create the dynamics of innovation. Long Range Planning, 29(4), 592. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(96)81509-3

Perryman, A., Butler, F., Martin, J., & Ferris, G. (2010). When the ceo is ill: Keeping quiet or going public? Business Horizons, 53(1), 21-29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2009.08.006

Ritholtz, B. (2013). Apple’s stock price post new product announcements. The Big Picture. Available at: http://www.ritholtz.com/blog/2013/10/apples-stock-price-post-new-product-announcements/. Access: Mar. 8, 2016.

Salas, J. (2010). Entrenchment, governance, and the stock price reaction to sudden executive deaths. Journal of Banking and Finance, 34(3), 656-666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.09.002

Schultz, T. (1961). Investment in Human Capital. The American Economic Review, 51(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.2307/1818907

Silverman, M. (2012). How product announcements affect Apple’s stock price. Mashable. Available at: http://mashable.com/2012/03/08/apple-product-stock-price/. Access: Jan. 8, 2016.

Stewart, T. (1997). Intellectual capital. New York : Doubleday/ Currency.

Sveiby, K. (1997). The New Organizational Wealth. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Warner, J., Watts, R., & Wruck, K. (1988). Stock prices and top management changes. Journal of Financial Economics, 20(C), 461-492. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(88)90054-2

Weisbach, M. (1988). Outside directors and ceo turnover. Journal of Financial Economics, 20(C), 431-460. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(88)90053-0

Notes

*

Scientific research work.

Author notes

a

Correspondence author.

E-mail: ademir@ufpr.br

Additional information

Para citar este artículo: Clemente, A., Ribeiro, F., & Colauto, R. D. (2018). The health

condition of steve jobs and

the value of apple’s shares. Cuadernos de Contabilidad, 19(48). https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cc19-48.hcsj