Introduction

The renovation of urban markets represents a fertile intersection between urban development and well-being in European cities. Recent EU frameworks (e.g., New European Bauhaus initiative) highlight the importance of creating inclusive, sustainable, and aesthetically pleasing spaces that serve multiple functions beyond their primary intended purpose. This multifunctional approach dovetails with the growing recognition that market spaces can shape neighbourhood regeneration while supporting the EU’s broader goals of creating healthier, more resilient and inclusive urban environments and populations (Affre, et al., 2024; Fuertes & Gomez-Escoda, 2022; Koopmans, et al., 2017; Warsaw, et al., 2021). The transformation of traditional neighbourhood markets into multifunctional community hubs represents a real-world application of these principles. However, understanding the impact of such transformations requires care to make an informed assessment of the effect well-intentioned interventions have on the communities in question.

Our paper looks at the Āgenskalns Market renovation project in Riga, Latvia and its impact on community well-being and social inclusion. Using a mixed-methods approach, we examine how the co-design and implementation of various solutions as part of a Horizon 2020 project influenced different aspects of health and well-being. This research contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the EU’s integrated approach to urban revitalisation, where market spaces can serve as laboratories for testing innovative solutions to contemporary urban challenges. However, it also illustrates the need for methodological creativity to ensure that the full extent of a solution’s impact can be traced and tracked.

We begin by providing a short overview of the project IN-HABIT and the Āgenskalns Market case study. We continue by explaining our approach to capturing the impact of Āgenskalns Market. We subsequently present our main results and reflect on the impact of IN-HABIT interventions. This paper argues that, despite their limitations, the data suggest that a multitude of changes have taken place, and the relative importance and impact of the market appears to be significant for the health and well-being of local residents. What is more, the study underlines the need for processual approaches that recognise unexpected forms of impact, while simultaneously being prepared to adjust methodological repertoires to avoid imposing ill-fitting metrics upon a complex situation.

Theoretical Framework: IN-HABIT and Social Impact Assessment

Our case study was developed within the framework of the Horizon 2020 project IN-HABIT. The project studies the connections between the urban context and health and well-being in small and medium-sized cities. Specifically, IN-HABIT aimed to deliver visionary and integrated solutions (VIS) that encompass social, cultural, digital and nature-based innovation, and foster inclusive health and well-being (IHW).

Work in the partner cities is organised around IN-HUBs. These are inclusive innovation spaces that are based on people-public-private partnerships (PPPPs) and nurture co-design, co-deployment, co-management, and co-monitoring processes (CO-CO-CO-CO). The IN-HUBS are places where different actors meet to design interventions, share and transfer knowledge, think about and assess impact, and discuss future directions of work. This enables different actors to work together to find the best solutions to improve IHW.

Unsurprisingly, the working methods of IN-HABIT are inspired by participatory action research, which is a methodology that actively involves community members in the research process to effect social change (Macdonald, 2012; Miller, 1994). This approach links participation, social action, knowledge generation and organisational learning in various diverse stakeholder ecosystems (Greenwood, et al., 1993), and it has been recognised as a way to address the participation of vulnerable groups in identifying linkages between public space use and well-being in an urban setting (Cheung, et al., 2022; Corburn, 2005). The Gender, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (GDEI) perspective is another critical component of the framework. This approach recognises that inequalities and discrimination significantly affect health and well-being. Research further supports that discrimination, whether structural or individual, has profound negative effects on both mental and physical health outcomes (Alvarez-Galvez & Salvador-Carulla, 2013).

Finally, IN-HABIT has an impact assessment framework that integrates top-down and bottom-up approaches to measure health and well-being. The top-down component was based on a review of existing frameworks from reputable entities (e.g., World Health Organisation, the OECD and the European Commission). Central to the framework is the assumption that health and well-being are influenced by a combination of individual, social, and environmental determinants. The framework also incorporates the subjective experience of well-being. Broadly speaking, five key dimensions form the backbone of the IN-HABIT assessment framework.

-

Subjective well-being (personal perceptions of happiness and

life satisfaction)

-

Spatial and environmental well-being (quality of physical

surroundings, green spaces, and environment)

-

Social well-being (social cohesion, community engagement,

and social support networks)

-

Healthy lifestyles (physical activity, diet, and substance

[ab]use)

-

Economic well-being (income levels, employment status, and

economic security)

This top-down approach was complemented with a bottom-up approach (co-designing and co-articulating pertinent indicators of IHW with various stakeholders) prior to gathering data. This allowed us to develop an assessment framework specifically tailored to the needs of each city. By aligning assessment and intervention strategies with local conditions, the VIS can significantly enhance the effectiveness of health and well-being initiatives.

The choices made above tie the project into contemporary debates regarding social impact assessment (SIA). SIA has gradually broadened beyond its initial scope to encompass a wide range of topics and sectors, gradually becoming more holistic in nature. There is a continuous evolution of measurement methods and theoretical frameworks (Alomoto et al., 2022; European Commission et al., 2014; Hazenberg & Paterson-Young, 2021). There are also important divergences that illustrate conflicting understandings of social impact. Activity-based approaches focus on tracking and evaluating actions taken or initiated by an intervention. This method assumes that these actions lead to impacts. Outcome-based approaches focus on tangible changes that can be captured by researchers and a connection can be established between an intervention and an impact. Secondly, we have tension between standardised and contextual metrics built into the research design. Standardised metrics favour comparability across cases (in our case, cities). This helps in benchmarking and comparison but may lack sensitivity to unique community needs and contextual specificities. This is where the contextual metrics developed via participatory action research can help by capturing nuanced, local impact indicators, often through direct stakeholder engagement.

IN-HABIT’s practical ambitions and its commitment to participatory research presents an ambivalent synergy between SIA and contextually tailored and processually determined interventions and metrics in the context of project-based research. This gives rise to the question we want to explore in our paper – what kind of impact can co-created and localised interventions have while simultaneously allowing researchers to capture and demonstrate it based on co-created metrics? We will explore this in the context of one of the pilot sites – Āgenskalns Market.

The Case and Rationale

The Riga case study was based in Āgenskalns. The goal, as part of IN-HABIT, was to promote health and inclusion in the neighbourhood by turning Āgenskalns Market into a multifunctional and creative urban food hub. The hub would mobilise the relatively undervalued potential of food, particularly in relation to culture and social activities.

Āgenskalns and the Market at a Glance

Āgenskalns is a neighbourhood in Riga, the capital city of Latvia. The total area of Āgenskalns neighbourhood is 4.6 square kilometres, and it has an official population of 23 223 (as of January 2024). The neighbourhood is well connected to other districts of the city, and its vicinity to the city centre and abundance of green zones make it an attractive place for residents and businesses. Āgenskalns neighbourhood is envisaged in Riga city development plans as a residential area to be developed by means of advancing green infrastructure and developing science and education centres as the campuses of three universities are located near Āgenskalns.

Āgenskalns Market is a central place and a landmark in the Āgenskalns neighbourhood. It is a historical food market opened in 1898 which has periodically functioned as the main market on the left bank of Daugava River (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Riga

(top), interior of Āgenskalns Market (bottom)

Figure 1.

Riga

(top), interior of Āgenskalns Market (bottom)

Source: Āgenskalns Market Team.

In 2018-2022 the market underwent vast reconstruction based on a private-public investment arrangement. It was reopened in 2022. With the help of the IN-HABIT project, the market was gradually transformed into a multifunctional food hub. The prior experience of Kalnciema Quarter (an SME and practice partner in the IN-HABIT project) in the development of another farmer market in Āgenskalns has shown the potential of food in revitalising urban spaces and social life (Grivins, et al., 2017). The intervention led to infrastructural improvements and an extensive programme of social, cultural and educational events organised at the market. Thus, it is a case where a traditional market is transformed into a multifunctional food hub – a place for sustainably produced and locally sourced food, but also a space for various economic, social, educational, cultural and recreational activities that contribute to the inclusion and well-being of the local community.

Focal Topics

The choice to focus on food was predicated on the idea that it is a powerful force that shapes individual health and social dynamics within urban environments (Roe et al., 2016; Richmond et al., 2024; Vaivadaite & Navickiene, 2024). Thus, it was a recognition of the practical import of food, rather than academic interest that underpinned this choice. Food is a way to address broader issues associated with inclusive health and well-being, and sustainability. Indeed, the plan foresaw that the market would continue to function as a space for selling goods. However, it would also provide cultural and educational opportunities, thus acting as a kind of community or cultural centre in the neighbourhood, contributing to different aspects of health and well-being.

This leads us to the importance of multifunctionality. Urban markets develop various other functions related to social, health, education, environment or the circular economy. These functions usually receive little support from the government, though they may have significant societal impact. Davila et al. (2022) suggest that the more urban agriculture projects depend financially on food production, the less they are inclined to develop a multitude of functions, and that the projects with different sources of income can afford to explore more options. This is evident in the operation of Āgenskalns market, which continuously seeks to diversify its sources of income while working with a coherent vision for the market. In addition to revenue from vendors, various public funding streams are sought to diversify and secure income, such as social entrepreneurship programmes, sponsorship and EU-level research and innovation programmes. This allows the market team to design activities with the involvement of various food system stakeholders, neighbourhood groups, cultural associations, educational establishments, media, and more.

There is also an architectural foundation for this multifunctionality. As an art nouveau building Āgenskalns market is a representation of belle epoque from the beginning of 20th century when central markets in European cities were among the most important urban institutions. They were places for conviviality and social interaction. Nowadays, historical markets try to reinvent and modernise their functions, and introduce new services by means of urban planning and architectural approaches (Béjaoui, 2022). Such efforts are also a key direction pursued within the New European Bauhaus (NEB) initiative. Specifically, multifunctionality aligns with sustainability goals and the zero net land take paradigm – the initiative promotes the revitalisation of existing functionally devalued urban spaces via renovation projects and their adaptation to serve new purposes that bolster neighbourhood vitality. (European Commission, et al., 2024, p. 287) Moreover, the multifunctionality of renovated spaces is contingent on implementing design principles that ensure accessibility, as well as diverse amenities that serve a wide range of users.

Multifunctionality is also linked to the topographic nature of a marketplace. Market processes – the negotiation and exchange of commodities – are place-based (Coles, 2021). This means that economic interactions taking place at the market are embedded in the rich materiality, sociality, sensuality and meanings associated with place. Seale (2016) views urban markets as places of material and symbolic economies. De Backer & Pavoni (2018) suggest that urban markets are places susceptible to aggregation of people and ‘thickening’ of their relationships. Āgenskalns Market provides an example of such a multifunctional food hub which is co-created in a participatory and collaborative process in IN-HABIT.

Finally, the multifunctionality of Āgenskalns Market was inherently linked to diversity and inclusion. Multifunctionality acts against economic, social and cultural exclusion, with the inclusivity of cultural events and opportunities for socialisation in the neighbourhood offsetting the potential exclusion or crowding out effects of other developments enabled by the market (cf. Morales, 2009). The team worked closely with market managers, private investors, other businesses, architects, urban planners, NGOs, research organisations and neighbourhood communities to openly design and develop solutions that meet the needs of various publics.

In conclusion, as pointed out by Woźniczka (2023), recently there has been a shift in the way public spaces are categorised and discussed in the academic community and beyond: “Instead of classifying them based solely on their functions, they are considered nowadays in terms of the aspirations and values held by those who manage them and those who use them” (Woźniczka, 2023). This aligns with the stated goals of Āgenskalns Market team and their alignment with NEB initiative. The overarching goal of NEB (led by the European Commission) is to foster a sustainable, inclusive, and aesthetically pleasing transformation of living spaces and communities across Europe (European Comission, n.d.). Furthermore, NEB emphasises the need for continuous improvement in the quality of urban planning. (Bilić & Šmit, 2024; Woźniczka, 2023). Āgenskalns Market serves as a real-life example of a public space striving to embody NEB priorities, including through the interventions deployed as part of IN-HABIT that aimed to strengthen the multifunctionality and inclusivity of the market.

Interventions

The interventions focused on: (i) improvements to physical public infrastructure in and around the territory of Āgenskalns Market in Riga, and (ii) the promotion of food related educational and consumption practices. This approach coalesced into four main directions of work: (i) transformation of the outdoor marketplace, (ii) community kitchen, (iii) minimisation of waste at the market, and (iv) an online food purchasing system. Over time, however, the fourth direction (online market) lost its relevance, and a decision was made to focus on a variety of social and cultural events (described in more detail below).

To achieve the vision described above, several activities were planned and implemented. The Riga team developed several “soft” (social and cultural) and “hard” (infrastructural, tangible) solutions.

1

In practice they have taken shape together and there is an inherent relationship between hard and soft solutions as infrastructural changes were the foundation for many cultural activities, while the latter allowed for the identification of further infrastructural needs that ensure that the market is both multifunctional inclusive.

Soft VIS

Soft VIS are aimed at achieving the IN-HABIT objectives of inclusion, well-being and sustainability and targeted at the general public as well as specific groups. In terms of thematic focus and means of intervention, the event can be classified as economic (trade), social, cultural, environmental and educational events.

Economic/trade events are the most frequent at the market. These are weekly flea and monthly vintage markets which bring together traders and customers interested in second-hand goods and reuse and repair practices. Trade events frequently relate to the minimisation of waste direction of the Riga project. They promote the ideas of sustainable lifestyles and circular resource use and potentially contribute to economic well-being.

Social events organised at the market take different forms: celebrations, competitions, creative workshops, sport activities, community sharing and gifting events, reading sessions, meal preparation, ethnic celebrations and others. They are oriented towards the general public. A common characteristic of social events is their interactive nature, thereby facilitating community engagement and skill development. They also act against discrimination and foster inclusion. Thematically speaking, social events may be related to different topics from festivals to food, different cultures, crafts and sports.

Cultural events have professional and amateur arts in their background. They include concerts, artistic performances, theatrical shows, dances, musical performances and more. Folk, jazz and choir music concerts are frequent at the market. Like social events, cultural events are offered free of charge and are aimed at the general public. Most of them take place in the transformed outdoor marketplace (community stage, community greenhouse). Cultural events are co-organised by the market team together with artistic collectives, such as musical groups, literary associations and cultural education establishments.

Educational events include activities such as cooking masterclasses, meal preparations, food recipe demonstrations, craftmanship training, bicycle repair sessions, gardening classes and more. These events usually take place at the community kitchen and transformed outdoor marketplace. Many educational events are food related as they address various aspects of sustainable consumption (e.g., food waste avoidance) and a focus on local and seasonal products. Teaching, demonstrating, learning and sharing knowledge about healthy nutrition and sustainable food consumption is essential to these events. Other topics of educational events may involve language training for the migrant population, entrepreneurship courses for Ukrainian war refugees, craftmanship classes, and physical health related workshops.

Hard VIS

Transformation of the Outdoor Marketplace

This VIS entailed the restoration of the area outside the market pavilion into an inclusive multifunctional space for social gatherings that combines food provision with cultural and educational opportunities. This involved renovating the market square and a community greenhouse, creating a community stage and community garden and installing an accessibility ramp. The primary actor is KQ, but the outdoor marketplace (both in form and in function) is envisaged as dynamically changing in response to demand.

Community (Co-Creation) Kitchen

This VIS entailed the creation of a dedicated area on the first floor of the market pavilion equipped with the necessary appliances to host community cooking and co-creation events targeted at different audiences. Most events are organised for free or at cost. The initial phase involved the clarification of the purpose of the community kitchen to potential users and ensuring health and safety standards for cooking in public spaces. The primary actor is the market team, but events are planned in cooperation with local NGOs, scientific organisations and public institutions to ensure that a wide range of people (including those at risk of discrimination) are involved in events organised in the community kitchen.

Lift to First Floor

This VIS entailed the installation of a lift in the historic neighbourhood market building to ensure accessibility and inclusivity. This addition will allow individuals with mobility impairments, including elderly residents, people with disabilities, and parents with young children, to fully enjoy all the market has to offer. By removing the physical barrier of stairs, the market can cater to a wider range of customers, promoting community engagement and supporting the needs of a diverse population. No specific co-design activities were needed as various members of the community continually voiced their concerns about the lack of a lift. The lift was procured via a procurement procedure.

Eco Island

This VIS entailed the establishment of an “eco-island” in the outdoor area of the market with the aim of improving waste sorting practices and reducing the volume of waste generated at the market. An internal audit of waste management at the market revealed that the biggest issue with waste sorting was among the vendors. As a result, a dedicated area for waste sorting was created, along with the appointment of a person responsible for educational outreach and assistance. Within just a few months, a reduction in waste management costs by an average of 600 euros per month was observed. Additionally, the environment and safety were improved, and access to the containers by local residents was restricted. Currently, a sorting system is being developed to meet the needs of market visitors. No specific co-design activities were organised, but various stakeholders, including environmental NGOs and waste management companies, were consulted.

However, these interventions presented a unique challenge when it came to examining their impact on social interaction, health and well-being. The next parts of the article summarises the methodologies used to capture and understand impact and the main findings of this exercise.

Methodology

Impact was assessed in a participatory and evolving way, bound by the timeline and deliverables of the IN-HABIT project. Data from 2021 and early 2022 serve as the baseline and point of departure for the analysis. The data were collected following a co-design process with stakeholders in which research partners determined the most plausible avenues of impact and main indicators of health and well-being to be employed in the project. Subsequently, the Riga team relied on qualitative and non-intrusive monitoring and evaluation methods, such as the expert judgement of valued partners and active stakeholders, regular site visits to conduct observations of activity at the market on different days of the week, and a storytelling exercise (20 stories recorded in 2023). The stories were told by residents who had been living in the neighbourhood for significant time and had experienced the transformation of the neighbourhood and the market. In parallel, a continuous monitoring of events took place between May 2022 and May 2024, documenting the number of different types of events and their impact dimensions according to the IN-HABIT framework outlined above.

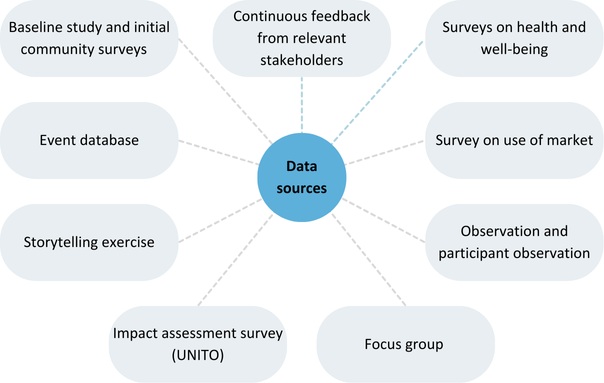

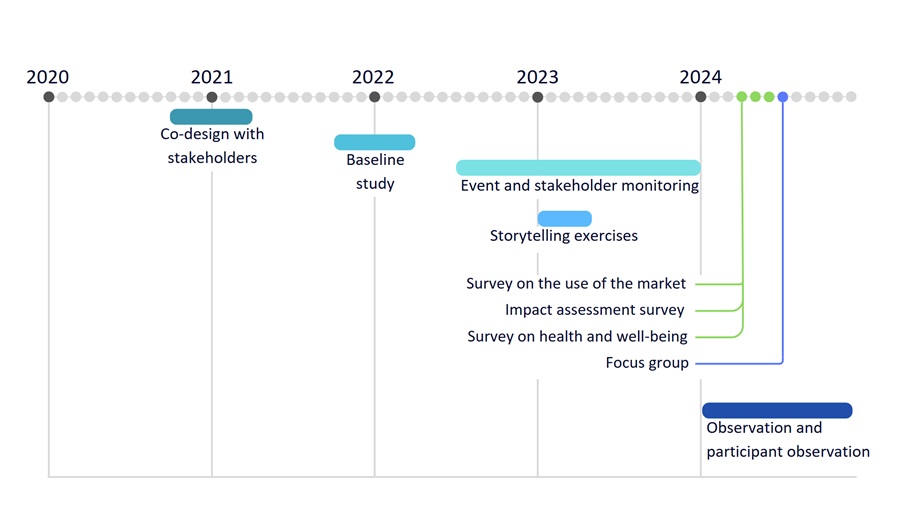

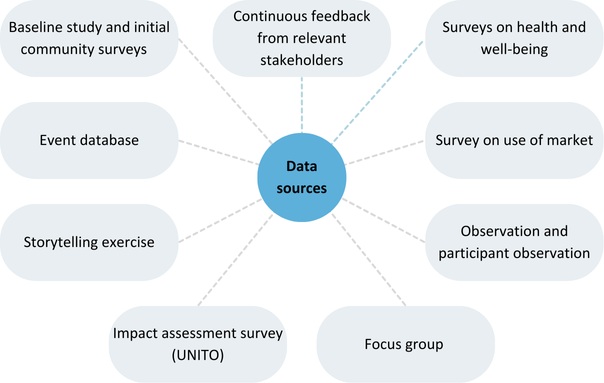

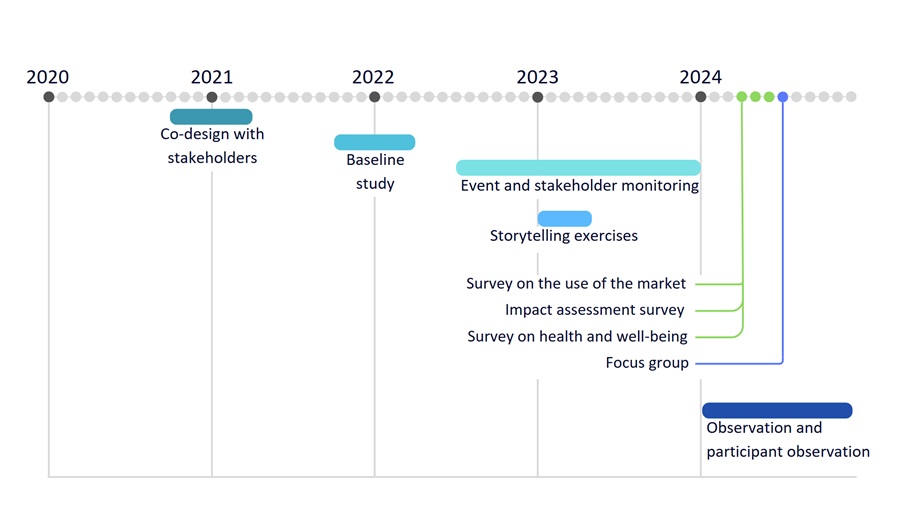

A more systematic data gathering exercise aimed at obtaining quantitative data for monitoring and evaluation purposes was carried out in the spring and summer of 2024. The gap is justified by the fact that the activities in the intervening period focused on establishing foundational elements and piloting interventions during the first two years since the market’s reopening (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Data sources

Figure 2.

Data sources

The initial step was a survey to understand how people make use of the market. It was launched in April 2024. It was an online survey, advertised at the market (QR codes) and on the social media profiles of the market and neighbourhood. A total of 963 responses were collected. The second and third surveys were explicitly designed to cover different aspects of health and well-being that formed the core of the baseline study in 2021. Building on the previous experience of the researchers, it was decided that the questionnaires must be shorter to ensure a reasonably high number of responses. Consequently, we decided to divide the baseline questionnaire into two parts – the first was primarily dedicated to physical and mental well-being, while the second focused on social and cultural well-being (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Research activity

timeline

Figure 3.

Research activity

timeline

Source: Own elaboration.

A focus group discussion was organised on 18 July 2024. It ran for approximately 90 minutes. The aim of the focus group was to discuss (i) the initial findings of the monitoring and evaluation exercise and (ii) the impact of the market with representatives of groups hitherto underrepresented in the data (the surveys in particular). Consequently, an effort was made of invite people who were 50 years or older and men. The discussion was held at Āgenskalns Market with 10 participants (five men, five women – four participants over the age of 50). In addition, BSC researchers made regular site visits to carry out observation and participant observation. An observation protocol was developed to ensure consistency and continuity between observers (four researchers from BSC), and 12 observation visits were made in 2024.

In summary, the fourth year of the project marked the full implementation of planned interventions and the design and implementation of data collection activities, which had not been systematic since the baseline study. The project’s focus on community engagement and phased implementation laid a strong foundation for and guided the methodology devised to measure the overall impact on the health and well-being of residents in Āgenskalns. It also meant that the methodology was adapted in response to emerging insights (see below).

Limitations

Monitoring and evaluation are essential to understanding the project’s true contribution, but it is crucial to acknowledge the methodological issues and limitations imposed by the challenging context in which it was implemented. Establishing a compelling link between the project’s activities and specific IHW outcomes, and extracting this from the influence of confounding contextual variables is challenging. Furthermore, the task of assessing the impact of Āgenskalns Market is rendered even more challenging by the turbulent political and economic climate of the period in which it was renovated, completed and opened to the public (e.g., pandemic, Russian invasion in Ukraine).

The study’s reliance on a non-random sampling strategy, primarily relying on visitors to the market and users of social media, introduces the potential for self-selection bias. Individuals who frequent the market may have particular interests or demographics that do not accurately represent the broader community (e.g., over 80 % of survey respondents were female). Consequently, the findings may not be generalisable to the entire population affected by the project. Additionally, the sample size of the study and the differences between the baseline and subsequent surveys may limit the statistical power to detect significant differences in outcomes.

Results

Changing Understanding of Impact

The team started the project with several general assumptions about the impact of VIS in the neighbourhood and beyond (see Appendix 1). However, the methodological approach of IN-HABIT required the involvement of the community in the monitoring and evaluation exercise. Consequently, a co-articulation of key indicators to focus upon was done via a participative and co-creative approach in 2020-2021, which relied on the perspective of local residents.

However, the research team had to refine this initial co-articulated framework during the course of the project, primarily due to significant political (e.g. Russian invasion in Ukraine) and economic (e.g., high inflation) changes in the intervening years. Practical considerations, such as research fatigue and data collection feasibility, also played a role in shaping the final selection of indicators. Finally, we prioritised those indicators where we could most plausibly attribute changes to the interventions implemented as part of our project. For example, initially, the monitoring and evaluation framework also considered various indicators of economic well-being (e.g., satisfaction with one’s personal financial situation), but it became apparent that many of these sub-dimensions were not meaningfully linked to project activities. Consequently, for the research and monitoring activities in 2024, we revised the initial list of assumptions about impact to focus on ones that could be captured by the methods we had at our disposal (see below). Our approach was further developed with focus group participants (July 2024), who were asked to provide their understanding of how the impact of the market should be approached and conceptualised now that it has been open for just over two years. The following themes were generated from an overview of the discussion transcript:

-

Increased activity in the market and neighbourhood overall.

-

Economic growth stimulated in the neighbourhood by the

market’s development.

-

Changing demographic profile of market visitors.

-

Inclusivity and representation of different age and interest

groups.

-

Expansion of the market’s functions.

-

Increased sense of agency in influencing the market’s

development.

-

Well-maintained and safe environment.

The latter were not, unfortunately, fully integrated into the monitoring framework that forms the basis of this paper but will be implemented in 2025. However, the data we have, while based on an evolving framework of indicators, paint a nuanced picture.

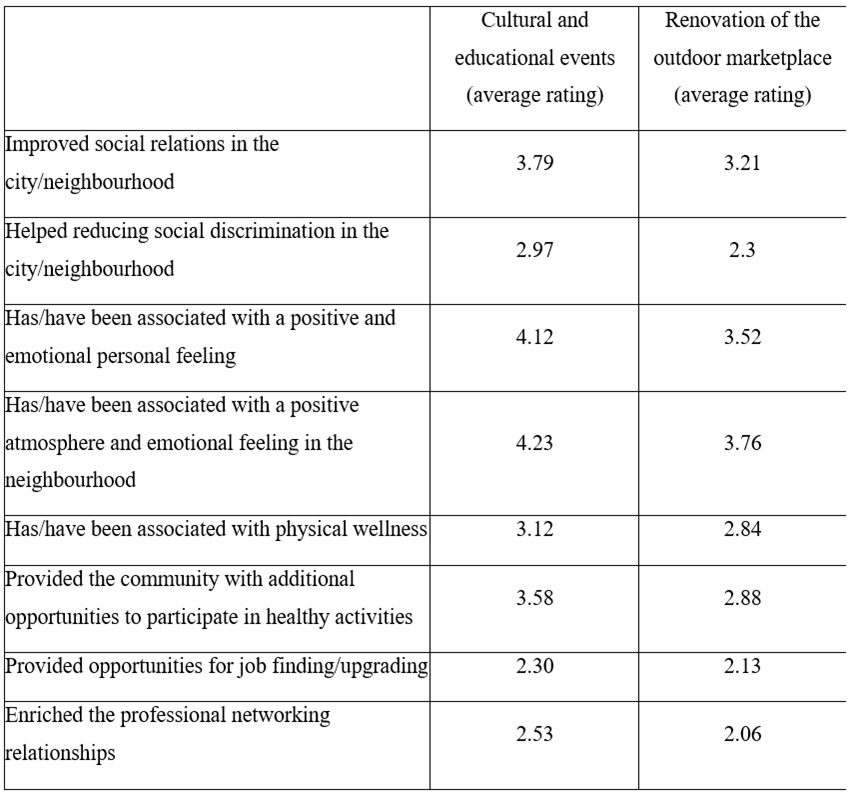

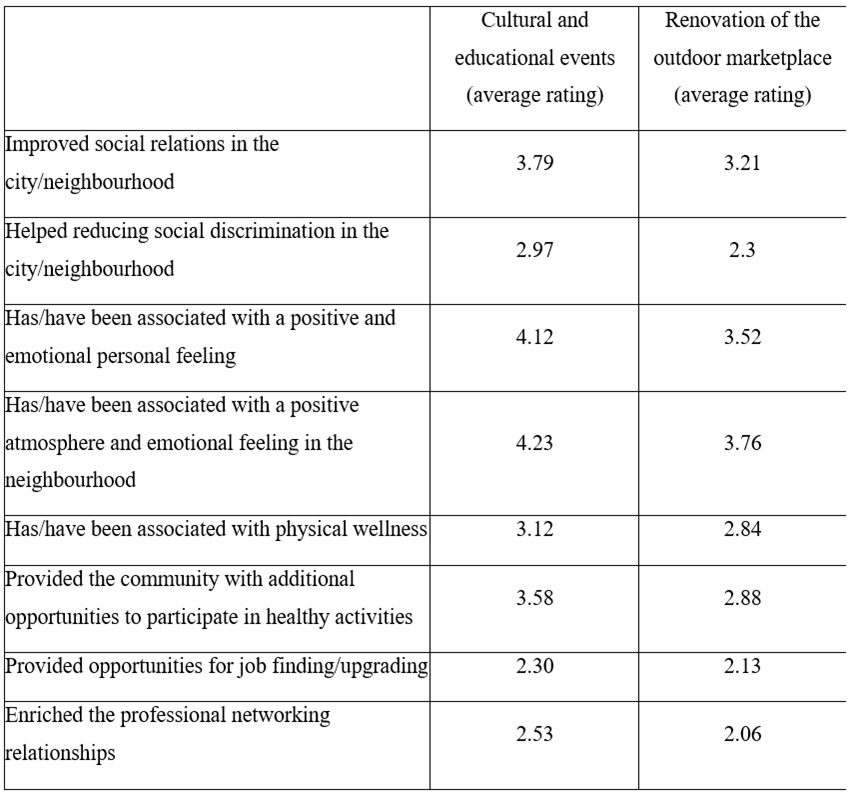

Surveys

In the surveys conducted to assess the impact of Āgenskalns Market on various dimensions of health and well-being, respondents were asked to evaluate one of the four directions of work using a six-point scale (0-5, with 5 being high positive impact) based on statements prepared by IN-HABIT project partners from the University of Turin (UNITO). The vast majority of respondents selected only two options. The results are summarised below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey on mental and

physical well-being (six-point scale (0-5))

Source: Own elaboration.

Generally, the two chosen directions of work appear to have contributed to emotional (subjective) well-being at both the individual and neighbourhood levels, with a positive impact (3 or higher) on social relations in the neighbourhood, though to different extents. A positive impact (3 or higher) can also be observed with regard to the provision of additional opportunities to participate in healthy activities, with cultural and educational events having a notably higher perceived impact. Notably, the reduction of social discrimination is lower than was initially anticipated (Table 2).

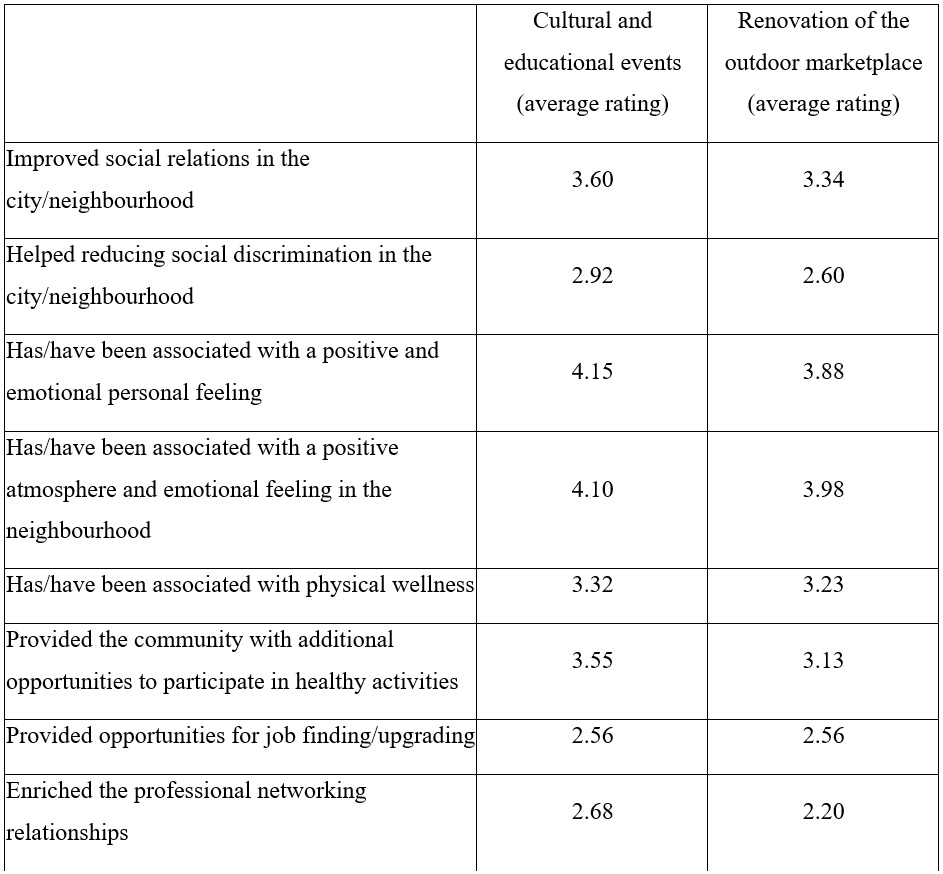

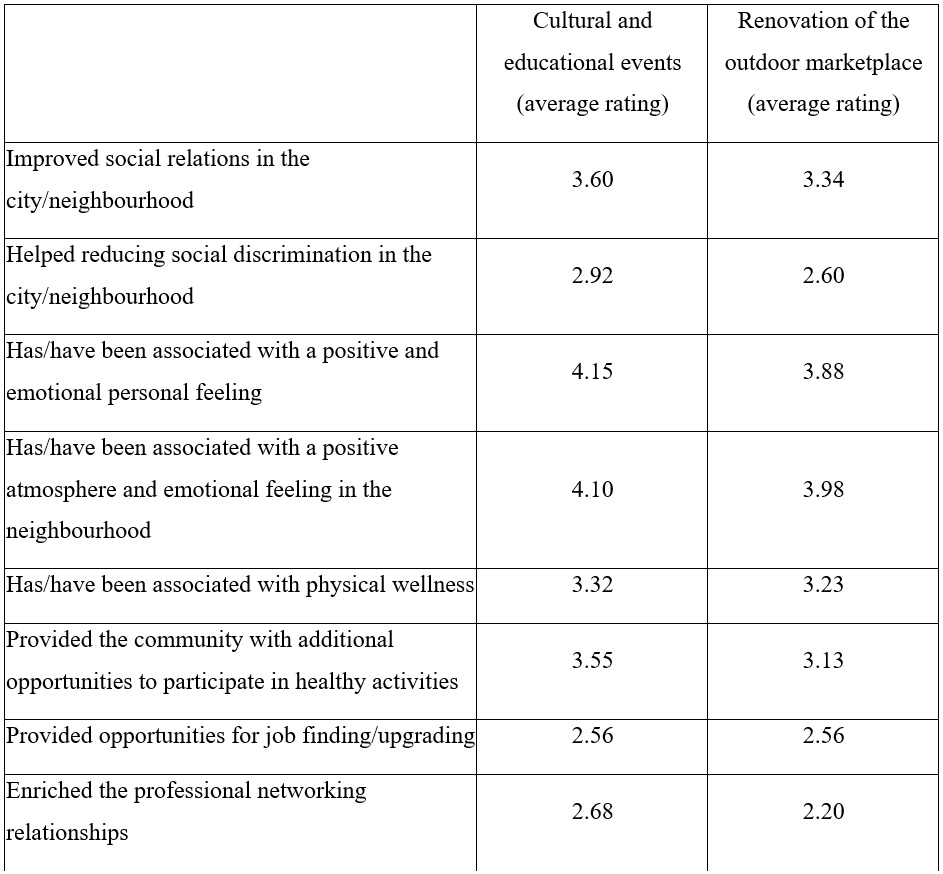

Table 2.

Survey on social and

cultural well-being (six-point scale (0-5))

Source: Own elaboration.

The results are broadly similar in the sense that the same statements have received a score above 3, with cultural and educational events scoring higher across the board. On the whole, the surveys indicated that the VIS in question scored well in terms of their impact on social, subjective and, to some extent, physical well-being, with economic well-being scoring lower. Environmental well-being was not explicitly addressed.

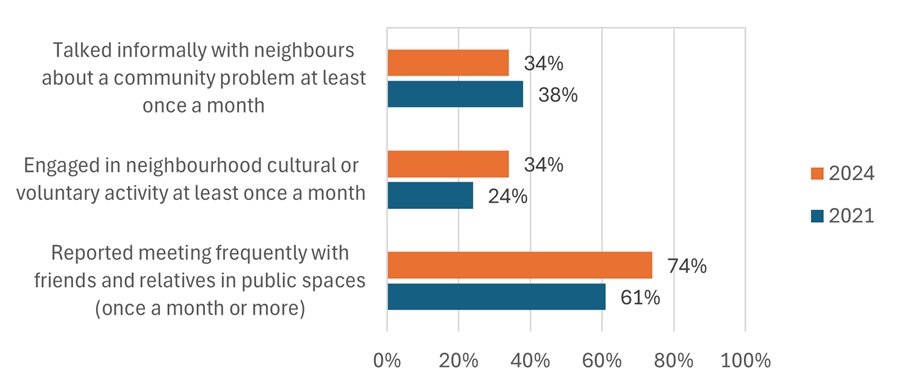

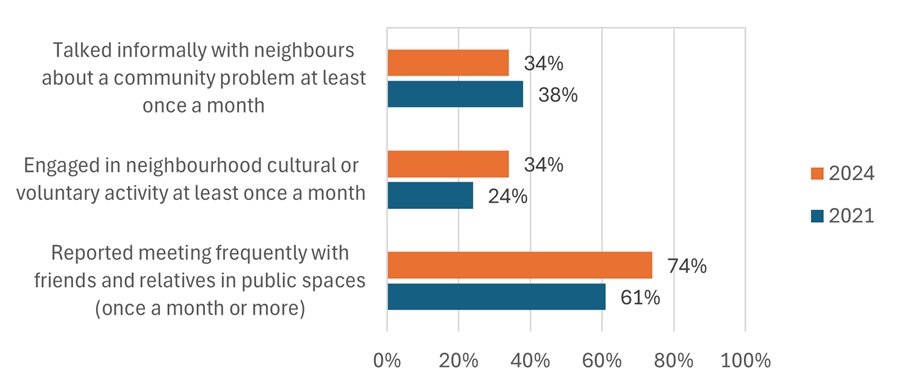

The chosen proxies for changes in social well-being (used in both the baseline study and the surveys in 2024) indicate moderate increases throughout.

In particular, in 2021, 61 % of the respondents reported meeting frequently with friends and relatives in public spaces (once a month or more). In 2024, this number has grown to 74 %. This suggests that the overall level of social engagement has increased in the intervening years, indicating that the market has become a place where people socialise (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Changes in social

well-being

Figure 4.

Changes in social

well-being

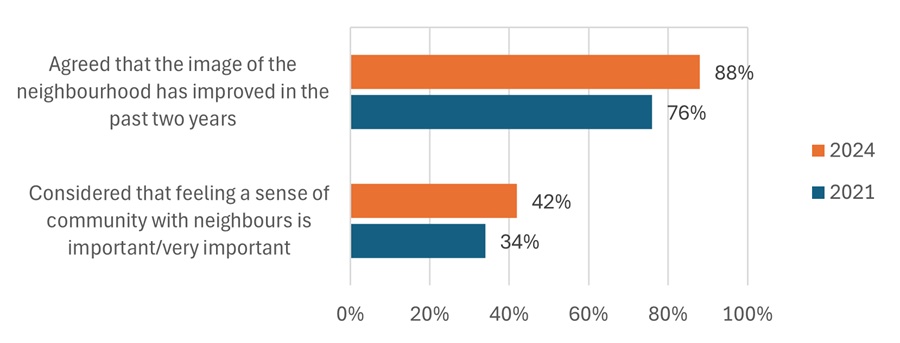

Source: Own elaboration.

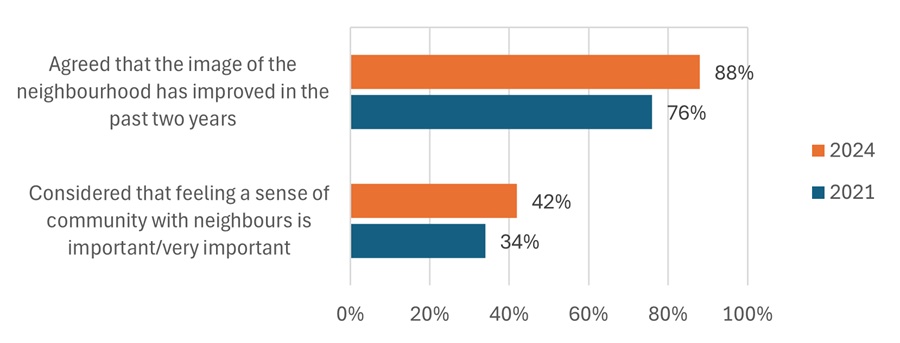

In 2021, 76 % of respondents agreed that the neighbourhood’s image had improved over two years. In 2024, the percentage had risen to 88 %, and the market was suggested as a key contributor. Responses to open-ended question further support this, with 19 respondents stating that the market has become more socially significant and that they regard it as the neighbourhood’s centre. Likewise, the percentage of respondents who replied that feeling a sense of community with people in one’s neighbourhood is important or very important to them had grown to 42 %. Furthermore, 31 % noted that the sense of community had become stronger over the last two years (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Changes in social

engagement

Figure 5.

Changes in social

engagement

Source: Own elaboration.

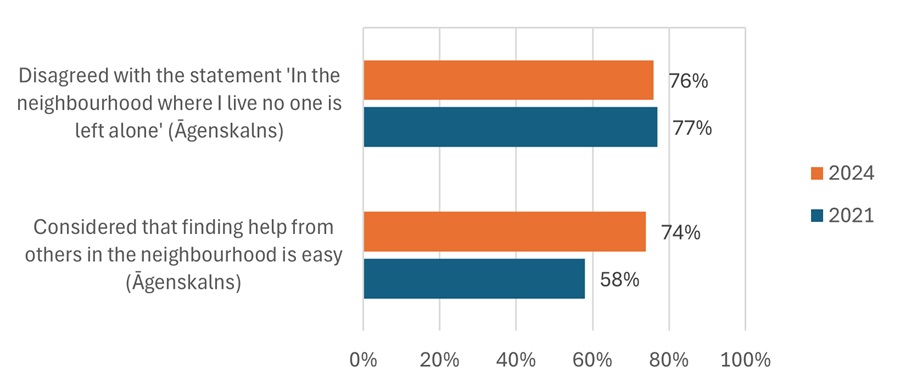

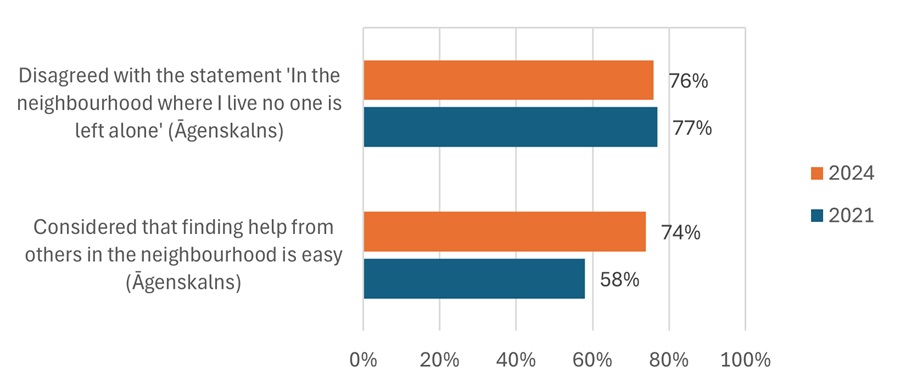

In regard to social inclusion, the picture is slightly more complicated (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Changes in

social inclusion

Figure 6.

Changes in

social inclusion

Source: Own elaboration.

The percentage of respondents who disagreed with the statement “In the neighbourhood where I live no one is left alone” remained largely the same. Nonetheless, in 2021, 58 % reported that finding help in their neighbourhood is easy. In 2024, this number had grown to 74 %.

Furthermore, the market is seen as an inclusive place, as suggested by the results from 2024:

-

94 % agree that Āgenskalns market is frequented by

people of all ages.

-

80 % agree that Āgenskalns market is accessible to

people with disabilities.

-

86 % agree that the market is a pleasant and beautiful

place to spend their free time.

In open-ended responses on factors that contribute to neighbourhood well-being, thirteen respondents replied the market promotes inclusivity. By contrast, ten respondents did not find the market inclusive. They felt it benefits only a subset of people, generally identifying affordability as a barrier, which ties into concerns regarding the market’s impact on economic well-being. Notably, some indicated that high prices have led them to visit the market less frequently, avoid purchasing general food items, or seek alternative shopping venues. Importantly, a few viewed the market primarily as a place that provides affordable shopping, with one positing that the shift to a multifunctional format has diminished this role to an extent.

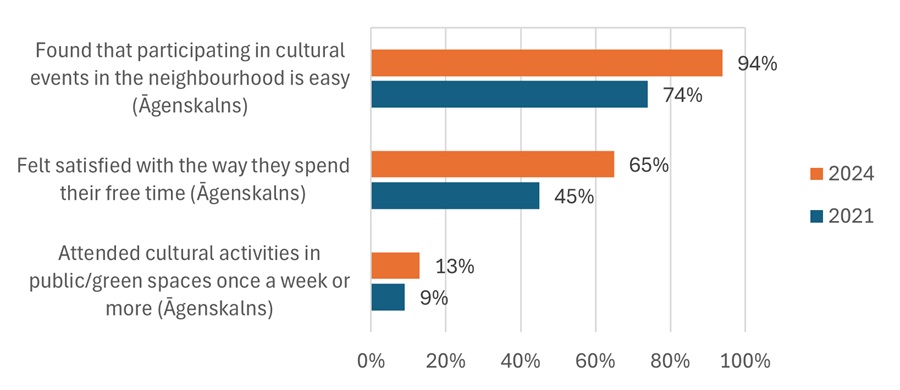

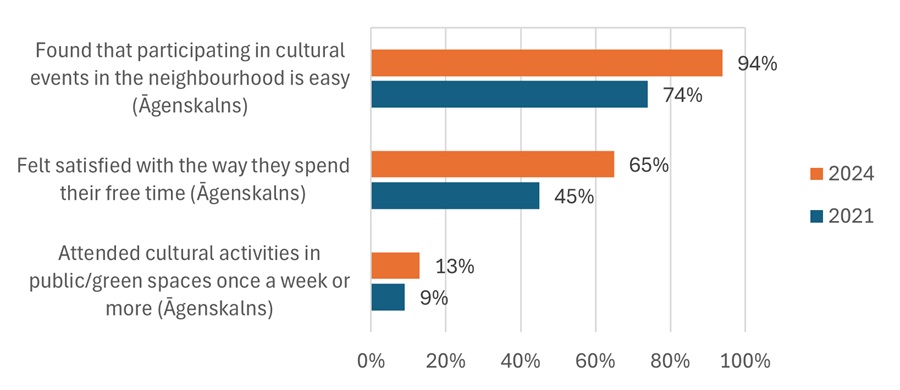

As regards the cultural offer and recreational opportunities in Āgenskalns, the results indicate a positive trend (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Changes in

recreational opportunities and attendance of cultural events

Figure 7.

Changes in

recreational opportunities and attendance of cultural events

Source: Own elaboration.

Ther percentage of respondents who replied that (i) it was easy to participate in cultural events and (ii) they were satisfied with the way they spend their free time had increased. In particular, 81 % of those who felt satisfied with the way they spend their free time noted that the market is at least partially responsible for these changes, with 37 % noting that the impact has been significant. The percentage of respondents who reported attending cultural activities in public and green spaces increased slightly, from 9 % in 2021 to 13 % in 2024. Of note is that in open-ended responses on aspects that contribute to neighbourhood well-being 75 respondents listed specific market functions, with the majority (65) citing various recreational activities such as attending events or socialising in the market’s dining areas. Overall, the market appears to have positively influenced the cultural offer and quality of leisure in the neighbourhood.

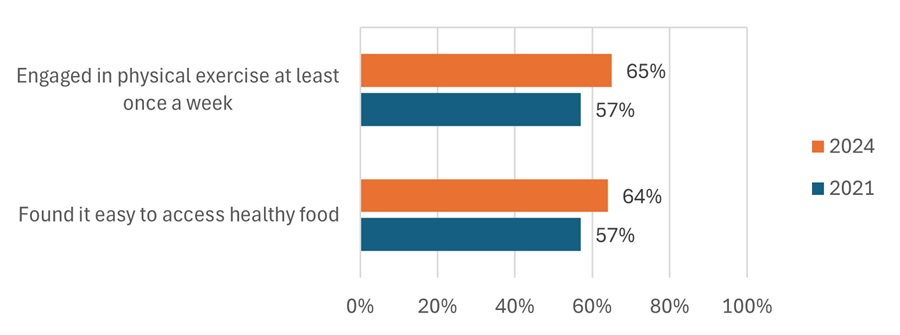

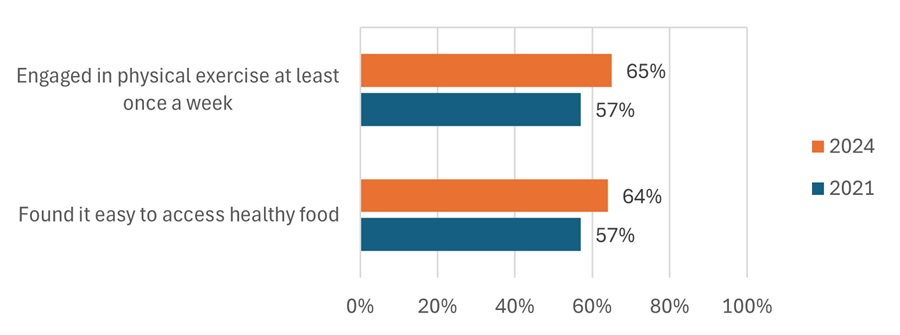

The table in the above section on VIS suggests that the activities at Āgenskalns market have made a moderately positive contribution to physical wellness (Figure 8). Survey responses to other questions seem to paint a similarly moderate picture. Crucially, however, 41 % of respondents noted that Āgenskalns market has positively affected the accessibility of healthy food.

Figure 8.

Contribution to

physical wellness

Figure 8.

Contribution to

physical wellness

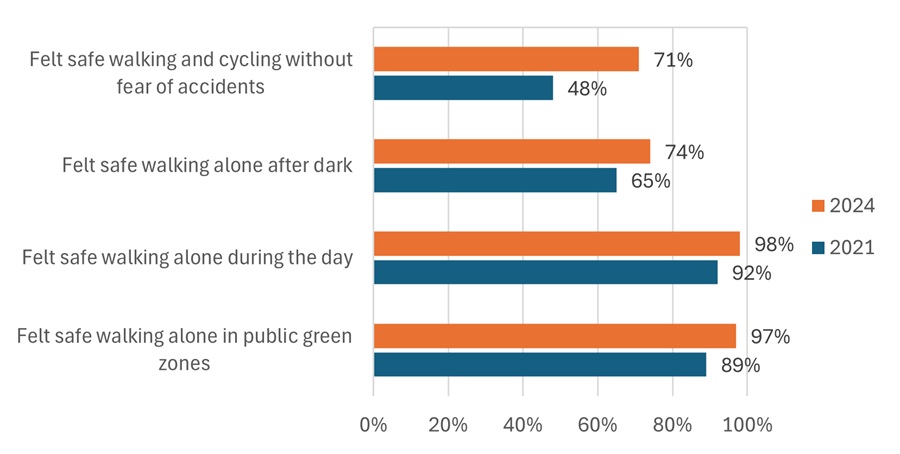

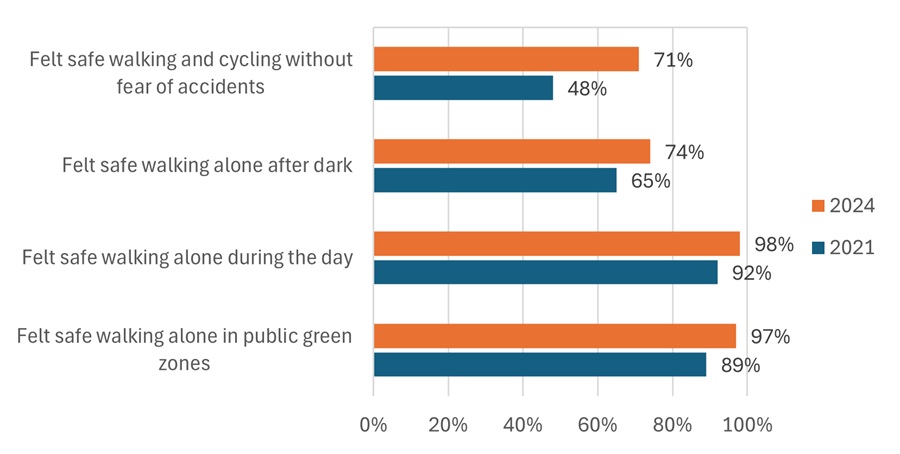

As for spatial well-being, survey results indicate that the perception of safety in the neighbourhood has moderately improved (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Changes in

the perception of safety in the neighbourhood

Figure 9.

Changes in

the perception of safety in the neighbourhood

A higher percentage of people feel safe walking and cycling without being afraid of becoming a victim of an accident, and people feel safer walking alone after dark. Responses to open-ended questions suggest a close connection between subjective and environmental/spatial well-being. Environmental aspects were noted by 45 survey respondents, with 28 reporting positive emotional responses such as joy, an uplifted mood, and a sense of comfort. Specific factors highlighted include a positive atmosphere (20 respondents), a well-maintained and clean environment (15), aesthetic appeal (9), and convenience (4). Respondents also noted a significant improvement in the market’s appearance compared to its pre-renovation state and appreciated the addition of various amenities that enhance accessibility (lift, street curbs, ramp, drinking fountain).

Focus Groups

Overall, all focus group participants regarded the revitalisation of Āgenskalns Market and its development into a multifunctional hub favourably. They noted that the market and neighbourhood have become livelier, drawing both locals and visitors from other parts of the city. Changes in visitor demographics were seen as an indicator that the market has become more attractive to people from various backgrounds, notably young people and families with children. The multifunctional format, a diverse range of activities, aesthetic appeal and accessible infrastructure were regarded as key contributing factors.

Focus group participants suggested that the revitalisation process could have a broader impact, such as the potential to stimulate the local economy and inspire greater social engagement, including more active participation in neighbourhood associations and community decisions. Moreover, as one participant noted, the expanding range of amenities helps foster satisfaction with one’s neighbourhood and increases the motivation to stay. Perceived reduction in individuals experiencing homelessness and substance abuse issues in the neighbourhood was also attributed to the market’s efforts.

However, participants also highlighted areas that require further improvement. Seniors highlighted the need for additional activities and spaces within the market tailored specifically to the needs of the elderly. Additionally, focus group participants expressed an overall concern that the new market format may alienate older adults and lower-income groups.

Storytelling Exercise

While the focus group discussions concentrated mainly on the impact of the current re-opened market, the stories told by local residents offered a glimpse into the past, describing the historic market and often comparing it to the revitalised one. The stories reveal that, compared to the past, the current vision of the market and its surroundings is seen as less fragmented. The storytellers are aware that the new concept of the market is broader, with a greater range of functions, and they also attend different cultural events, corroborating the claim that the perceived functions of the market have become more diverse, due, at least in part, to the VIS implemented at the market. Finally, it can be observed that market visits, both in the past and the present, often function as part of the weekly routine of residents. The regularity of the visits underlines the potential of the market to contribute to local inhabitants’ subjective and social well-being.

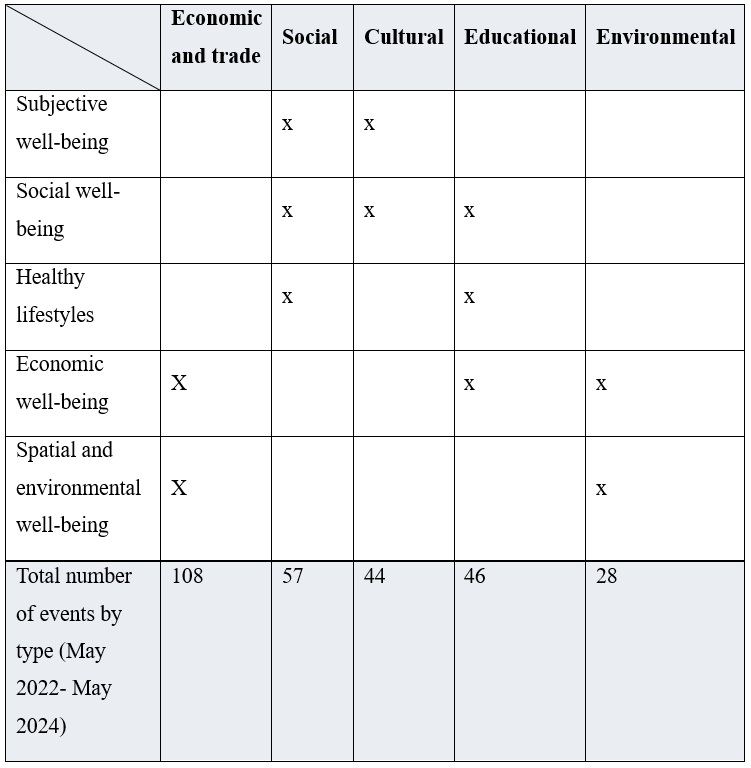

Observations and Event Monitoring

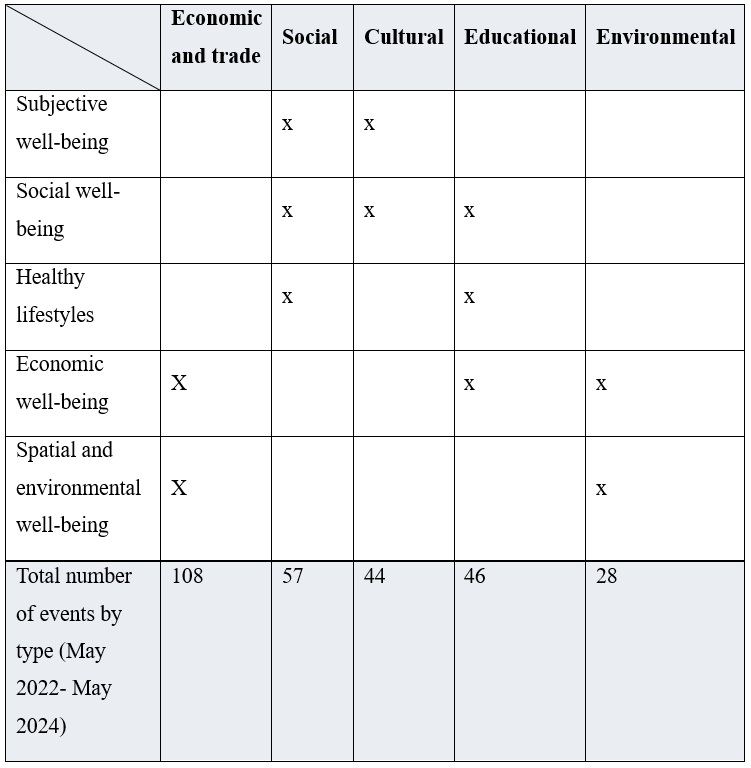

Regular observations and event monitoring allowed us to categorise different types of events taking place at the market, including trade, social, cultural, educational, and environmental events. All event types share a common goal of enhancing local residents’ well-being across different impact dimensions. It must be noted, however, that different event types may have varying frequency and attendance, therefore it is beneficial to describe the impact of each event type separately (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main impact

dimensions of different types of events

Source: Own

elaboration.

Economic and trade events (most frequent) may also seem the most “traditional” for a marketplace; however, in Āgenskalns Market, they are often advertised with certain seasonal and sustainability themes, making them potentially more appealing to different target audiences. For instance, in autumn 2024, the market had “Mushroom Day”, “Potato Festival”, “Apple Celebration”, and “Pumpkin Day”, as well as monthly Vintage Market Sundays. The market team has sought ways to promote economic well-being through this type of event; for instance, by giving a chance to people to save by taking advantage of special promotions. Some events also improve environmental well-being by offering the reuse and exchange of things and promoting circular practices.

Social events are less frequent, and their main impact dimensions are subjective and social well-being (inclusion, social cohesion, participation and social engagement, acting against discrimination, and promoting equal opportunities). However, a substantial contribution was also observed with regard to the promotion of healthy lifestyles (leisure and free time, cultural consumption and production, physical health) and subjective well-being (sense of belonging, psychological well-being, experiencing togetherness with others).

Cultural events are aimed primarily at social well-being (inclusion, civic and social engagement) and subjective well-being (sense of belonging, psychological well-being). They contribute to healthy lifestyles (in terms of cultural consumption and production, leisure and free time), although the cultural offer at the market is seldom framed in the same way as the offer of cultural institutions and art establishments. Some cultural events may have a pedagogical intention, for example, artistic performances aimed at improving the participants’ critical thinking.

Educational events are related to food and sustainable consumption; therefore, the primary impact pathway is the popularisation of healthy lifestyles (healthy food habits, knowledge and skills of meal preparation, food saving, food planning, healthy nutrition, local and seasonal products, etc.). Learning to cook, sharing food knowledge, and practising meal preparation together can be considered a contribution to the physical well-being of participants as these activities enhance skills and competencies and eventually may result in more healthy nutrition and consumption habits. This is particularly important in the case of young people and children. In the meantime, educational events as a form of joint learning and group activity contribute also to social well-being (inclusion, engagement), subjective well-being and spatial and environmental well-being.

The impact of environmental events relates mainly spatial and environmental well-being of people participating in activities such as tree planting at the market, growing in the community garden, plant and seed exchange, and gardening workshops. Environmental events also relate to economic well-being as activities usually involve DIY-style workshops and practical learning of environmental solutions. Environmental events aim to develop the skills of participants and result in improved green territories and solutions for the entire Āgenskalns community.

For the regular observations that we conducted in the market, we visited the market during regular days and events. However, when analysing the event observations, we noticed a challenge to identify which observed characteristics would most relate to the impact of an event on the individuals and the community. One of the observed characteristics was the increased flow of market visitors during the events. The observation was also supported by the preliminary data collected by people counters that were installed in the market. Nevertheless, the increase in the number of visitors did not suggest a straightforward conclusion about the expected impact.

We also took note of the visitor groups and types of interactions between the visitors. As a result, while not entirely sufficient as a stand-alone method, the observations helped to corroborate the results from other methods such as surveys and focus groups. For instance, they supported the finding that the multifunctional market has positively influenced the cultural offer and quality of leisure time in the neighbourhood.

Discussion

Taking our research question and the main dimensions of the IN-HABIT IHW framework as our point of departure, several observations can be made. Overall, our findings suggest that the project has had a positive influence on subjective and social well-being in Āgenskalns and improved the perception of and opportunities for socialisation in the neighbourhood. Data indicate that several hard VIS developed as part of IN-HABIT have enabled crucial attributes of place formation that contribute to spatial well-being in the market itself and the neighbourhood. As a “place” (both social and physical), the relative importance and impact of the market as an urban landmark and cultural centre extends beyond the neighbourhood.

The formation of a hybrid and multifunctional public space has an impact on IHW that exceeds the specific contributions of each VIS developed and implemented as part of the project, aligned with the project’s idea that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. The multifunctionality of the market appears to be generally appreciated by local residents and visitors and this has allowed Āgenskalns Market to live up to the NEB promise of reinvigorating underutilised public spaces and revitalising social life in the neighbourhood. Indeed, it has allowed social relationships to “thicken” (De Backer & Pavoni, 2018). Nonetheless, the impact of the multifunctional market in terms of physical and spatial well-being requires further exploration to uncover underlying complexities that complicate the narrative and suggest competing visions for the market. What is more, economic well-being is a contentious topic, as evidenced by the perception of the market as a place for comparatively well-off individuals.

The ambivalence surrounding the economic aspects has significant implications for the market’s role in community life. While the VIS are dedicated to promoting various forms of inclusion, the research efforts have uncovered potential forms of exclusion suspected and acknowledged by the Riga team. However, respondents also acknowledged that many activities and services, such as cultural and social events, the green areas and outdoor facilities are accessible free of charge and are appreciated. This, to a certain extent, counteracts the exclusionary effects of higher market prices and perceived gentrification. Overall, therefore, the intended multifunctionality of the space has had a multifaceted effect, with primarily positive, but also some negative, externalities, such as alienating older adults and lower-income groups. Indeed, integrating ageing communities, as well as competition with wholesalers are common challenges faced by modern urban markets, as cities undergo significant changes impacting local communities and social cohesion (Vaivadaite & Navickiene, 2024), and Āgenskalns Market has to deal with similar issues.

Overall, the presence of self-selection bias is a serious issue with the data at our disposal, which may conceal certain aspects of how the market is perceived. For instance, while certain potentially problematic aspects were identified, we note that a more targeted research effort is necessary to ensure that a full account of negative impacts and externalities can be made at the end of the project. Fundamentally, our paper highlights the challenges of measuring the intangible yet significant aspects of the project’s impact, such as changes in community dynamics and social cohesion. What is more, our data only hint at the potential ripple effects of the market on the surrounding area.

It is a somewhat paradoxical admission that a central challenge that we encountered in our research activities was identifying and delineating the impact of project interventions on Āgenskalns. There is an inherent difficulty in isolating the specific effects of VIS from the broader influence of the market revitalisation project and concurrent transformations in the city. Furthermore, this was not a problem that only affected the research team and its attempts to track and trace impact. Our data suggest that our respondents also had difficulty associating particular impacts with the actions made possible by IN-HABIT. Indeed, this is why we often chose to discuss the impact of the market. Finally, our understanding of how the interventions could impact IHW evolved during the course of the project, in response to feedback from various stakeholders and changing circumstances. Thus, to answer our research question – the impact of co-created interventions can be significant, but co-created metrics and assessment frameworks present challenges for researchers.

The above has interesting implications when considered from the perspective of social impact assessment research (SIA), especially in the context of project-based research. Our attempts to capture impact are a combination of activity-based and outcome-based approaches. We have events and activities (activity-based) and impacts captured via questionnaires (outcome-based). Each is assumed to demonstrate impact, while only the latter captures it. Secondly, we have a combination of standardised and contextual metrics built into the research design. In the project, this is evidenced by the intersection of top-down (IN-HABIT framework) and bottom-up approaches (co-created indicators). However, the latter in particular presented methodological challenges as the forms of and avenues of impact suggested by the stakeholders forced researchers to continuously refine the framework and experiment with methodologies that would be able to capture them.

Indeed, the final point summarises the main experience of this process and highlights numerous challenges when it comes to thinking about impact. Impact requires evidence, but it also requires conceptualisation. In a participatory and transdisciplinary approach that simultaneously (i) develops multifaceted VIS and (ii) attempts to understand how these impact a neighbourhood, researchers and practitioners must deal with uncertainty both with regard to how impact can be described and how it can be demonstrated. Without the clarity of a pre-defined methodological toolkit that is tailored to a clear notion of what kind of effect (and in what way) project interventions will have, teams must rely upon and train their methodological creativity to show impact without imposing ill-fitting metrics upon situations that do net lend themselves easily to simple methodological solutions. However, this may not always be possible as the deadlines and deliverables associated with project-based research may force researchers to simplify their approaches and accounts.

From a more practical point of view, our process and results illustrate the potential for synergies between the IN-HABIT framework and recent work on restorative cities (Roe & McCay, 2021). The project’s impact assessment framework developed city-specific metrics for restorative urban projects by tracking indicators relevant to various communities and dimensions of well-being. The restorative cities approach encourages community engagement and ownership of urban spaces, fostering belonging and social resilience, while the IN-HABIT impact assessment framework was predicated upon participatory approaches that involved stakeholders in defining goals, indicators, and evaluation criteria. Explicitly relating specific questions and indicators to the core pillars of restorative cities in the next iteration can allow for an evaluation of how the design of urban spaces impacts social dynamics and individual well-being and contribute to the broader agenda of restorative cities.

Furthermore, a participatory impact assessment framework can theoretically empower residents to be active in the assessment process, making them partners in both the design and evaluation of restorative spaces. Engaging communities in both restorative city initiatives and their impact assessments could make for more accurate and relevant measurements of social value added, and greater alignment between project goals and community needs. This would also have benefits from an urban planning perspective. By incorporating participatory impact assessment into the planning and ongoing evaluation of projects, cities can track how well restorative interventions sustain their benefits over time.

Conclusions

The renovation of urban neighbourhood markets represents an attempt to create spaces and places that serve multiple functions beyond their primary intended purpose. Our paper looked at the example of Āgenskalns Market to explore how transformations of neighbourhoods can impact community well-being and social inclusion. The case study that formed the basis of this paper was developed and explored as part of the Horizon 2020 project IN-HABIT. What is more, our understanding of health and well-being is fundamentally shaped by the projects’ conceptual framework and participatory approach.

In our case, it is not always possible to claim with certainty whether a particular effect can be directly attributed to the market and the interventions made possible by IN-HABIT. Nonetheless, we noted that, despite their limitations, our data suggest that a multitude of changes have taken place and that, as a “place” (both social and physical), the relative importance and impact of the market appears to be significant for the health and well-being of local residents. We also noted that some dimensions of well-being have benefited more than others, and the relationship between the market and economic well-being in particular remains contentious.

Finally, we noted the potential synergies between the approach taken in IN-HABIT and the broader agenda of restorative cities. Indeed, the possibilities for cross-fertilisation are both practical and scientific. The key point, however, is that we must be careful to recognise unexpected and novel forms of impact, while simultaneously being prepared to adjust our methodological repertoire to avoid imposing an ill-fitting metric upon a complex situation.

References

Affre, L., Guillaumie, L., Dupéré, S., Mercille, G. & Fortin-Guay, M. (2024). Citizen Participation Practices in the Governance of Local Food Systems: A Literature Review. Sustainability, 16(14), 5990. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16145990

Alomoto, W., Niñerola, A., & Pié, L. (2022). Social impact assessment: A systematic review of literature. Social Indicators Research, 161, 225-250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02809-1

Alvarez-Galvez, J., & Salvador-Carulla, L. (2013). Perceived Discrimination and Self-Rated Health in Europe: Evidence from the European Social Survey (2010). PLoS ONE, 8(9), e74252. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0074252

Béjaoui, F. (2022). The Central Market in Tunis: Fondouk Al-Ghalla. In H. Neveen (Ed.), Architecture and Urban Transformation of Historical Markets: Cases from the Middle East and North Africa (1st ed., pp. 52-66). Routledge.

Bilić, B., & Šmit, K. (2024). Evaluation of the New European Bauhaus in urban plans by land use occurrence indicators: A case study in Rijeka, Croatia. Buildings, 14(4), 1058. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings14041058

Cheung, S. Y. S., Lei, D., Chan, F. Y. F., & Tieben, H. (2022). Public Space Usage and Well-Being: Participatory Action Research with Vulnerable Groups in Hyper-Dense Environments. Urban Planning, 7(4), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v7i4.5764

Coles, B. (2021). Making Markets Making Place. Geography, Topo/graphy and the Reproduction of an Urban Marketplace. Palgrave Pivot Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72865-6

Corburn, J. (2005). Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6494.001.0001

Davila, F., Maughan, N., Rixen, T., & Visser, M. (2022). The Multifunctionality of Urban Agriculture Projects in Brussels. Acta Horticulturae, 1356, 219-232.

De Backer, M., & Pavoni, A. (2018). Through Thick and Thin: Young People’s Affective Geographies in Brussels’ Public Space. Emotion, Space and Society, 27, 9-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2018.02.005

European Commission: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion & Clifford, J. (2014). Proposed Approaches to Social Impact Measurement in European Commission Legislation and in Practice Relating to EuSEFs and the EaSI : GECES Sub-Group on Impact Measurement 2014. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/28855

European Commission: Joint Research Centre, Lourenço, P. B., Maloutas, T., Romano, E., Santamouris, M., Negro, P., Widera, B., Ansaloni, F., Balaras, C., Katurić, I., Kolokotsa, D., Rossetto, T., Senatore, G., Tomaszewicz, A., Medeiros, E., Gkatzogias, K., Pohoryles, D., Acri, M., Becerik-Gerber, B., … Vecco, M. (2024). A practical Guide to the New European Bauhaus self-assessment method and tool (Romano, E., Negro, P., Gkatzogias, K., Eds.). Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/9581060

European Commission. (n.d.). About the initiative. New European Bauhaus. Author. https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/about/about-initiative_en

Fuertes, P., & Gomez-Escoda, E. M. (2022). Supplying Barcelona: The Role of Public Market Halls in the Construction of the Urban Food System. Journal of Urban History, 48(5), 1121-1139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144220971821

Greenwood, D. J., Whyte, W. F., & Harkavy, I. (1993). Participatory Action Research as a Process and as a Goal. Human Relations, 46(2), 175-192. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600203

Grivins, M., Keech, D., Kunda, I., Tisenkopfs, T. (2017). Bricolage for Self-Sufficiency: An Analysis of Alternative Food Networks. Sociologia Ruralis, 57(3), 340-356. https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12171

Hazenberg, R., & Paterson-Young, C. (Eds.). (2021). Social Impact Measurement for a Sustainable Future: The Power of Aesthetics and Practical Implications. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-83152-3

Koopmans, M. E., Mettepenningen, E., Kunda, I., Keech, D., & Tisenkopfs, T. (2017). Creating Spatial Synergies around Food in Cities. Urban Agriculture & Regional Food Systems, 2(1), 1-9. https//doi.org/10.2134/urbanag2016.06.0003

MacDonald, C. (2012). Understanding Participatory Action Research: A Qualitative Research Methodology Option. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 13(2), 34-50. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v13i2.37

Miller, N. (1994). Participatory action Research: Principles, Politics, and Possibilities. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 1994(63), 69-80. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.36719946308

Morales, A. (2009). Public Markets as Community Development Tools. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 28(4), 426-440. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X08329471

Richmond, A. R., Harrell, K. N., Ridgeway, J. R., & M. Ware, A. (2024). Food for Thought: Unveiling Urban Transitions in a Small US City through the Lens of Foodscape Typologies. Landscape Research, 50(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2024.2377163

Roe, J., & McCay, L. (2021). Restorative Cities: Urban Design for Mental Health and Well-being. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Roe, M., Sarlöv Herlin, I., & Speak, S. (2016). Identity, Food and Landscape Character in the Urban Context. Landscape Research, 41(7), 757-772. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1212324

Seale, K. (2016). Markets, Places, Cities. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315733234

Vaivadaite, S., & Navickiene, E. (2024). The Potential of Food Markets in the Contemporary City: A Systematic Literature Review. Architecture and Urban Planning, 20(1), 112-123.

Warsaw, P., Archambault, S., He, A., & Miller, S. (2021). The Economic, Social, and Environmental Impacts of Farmers Markets: Recent Evidence from the US. Sustainability, 13(6), 3423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13063423

Woźniczka, A. (2023). The Impact of Policy Initiatives on the Design of Public Spaces on the Example of the New European Bauhaus. Architectus, 3(75), 539-549. https://doi.org/10.37190/arc230308

Appendix

1. Initial assumptions about potential impact

Assumption 1: The multifunctional hub can improve physical health

-

Increased physical activity: The renovated market (more

accessible design and potential for hosting community events) may encourage

residents to walk or cycle to the market, leading to increased physical

activity.

-

Improved nutrition: A more diverse and accessible market could provide

residents with healthier food options and courses about the importance healthy

nutrition, potentially improving their overall diet.

Assumption 2: The multifunctional hub can improve mental health

-

Social connection: The market’s role as a community hub can foster social

interaction in the neighbourhood.

-

Reduced isolation: The market’s accessibility and cultural offer can help

reduce feelings of isolation, particularly among disadvantaged or vulnerable

groups.

-

Stress reduction: Engaging in community activities and enjoying cultural

events can contribute to emotional well-being.

Assumption 3: The multifunctional hub can increase social cohesion

-

Community hub: The renovated market’s role as a community hub can foster a

sense of belonging and connection among residents.

-

Shared spaces: The market’s public spaces can provide opportunities for

people to interact, socialise, and build relationships.

-

Cultural exchange: The market’s diverse programming can promote cultural

exchange and understanding.

Assumption 4: The multifunctional hub contributes to spatial

well-being

-

Enhanced public space: The renovation of the market

can create or improve public spaces that are inviting, accessible, and

aesthetically pleasing, remaking the “face” of the neighbourhood.

-

Sense of place: The market’s revitalisation can strengthen the

neighbourhood’s sense of place and identity.

-

Reduced social isolation: The market’s accessibility and

public spaces can help reduce feelings of isolation, particularly among

marginalised groups.

Assumption 5: The multifunctional hub has spillover effects on

quality of life in the neighbourhood.

-

Increased community pride: A renovated market can enhance

the neighbourhood’s aesthetic appeal and contribute to a sense of community

pride.

-

Economic benefits: The market’s revitalisation may attract new businesses to

the neighbourhood and create jobs, leading to improved economic opportunities

for residents.

-

Educational opportunities: The market’s function as a

cultural and educational venue can provide residents with access to learning

activities.

Assumption 6: Turning a neighbourhood market into a multifunctional

hub presents potential challenges that need to be addressed.

-

Gentrification: The increased accessibility and potential for higher

property values could lead to displacement of long-time residents.

-

Economic inequality: The market’s focus on inclusivity must be balanced with the

need to generate revenue to sustain operations.

-

Cultural sensitivity: The renovation should be mindful of the neighbourhood’s

cultural heritage and avoid erasing its unique character.

Notes

*

Research paper / Artículo de investigación científica

1

IN-HABIT

employs the distinction between between “soft” and “hard” solutions for the

purposes of simplicity.

Author notes

a Corresponding author / Autor de

correspondencia. E-mail / Correo electrónico: emils.kilis@bscresearch.lv

Origin of this Research

This research has been funded under the IN-HABIT (Incluside Health and Well-being in Small and Medium-sized Cities) project as a part of the Horizon 2020 Program (Grant Agreement No. 869227). The contents of this document do not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. The responsibility for information and opinions expressed herein lies solely with the authors.

Additional information

Cómo citar / How to cite: Kilis, E., Mileiko, I., Braslins, M., Tisenkopfs, T., Meiberga, U., Trizna,

D., & Cimdins, R. (2025). Tracing and Tracking the Impact of a Contemporary Marketplace:

The Case of Āgenskalns Market. Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 18. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cvu18.ttic