Introduction

The intellectual and practice-oriented experiences of public participation in (collaborative) urban planning has today an established legacy over time, with wealth and varieties in terms of methodologies for public engagement, tools, approaches and process of formalisation and in some cases, institutionalisation in different localities (Lane, 2005; Hofer & Kaufmann, 2023; Charland, 2024). In the last years, the attention to multi-level participatory framework has been diverted to analyze sustainability transitions as a means to tackle interconnected polycrises encompassing climate, societal, and economic challenges adversely affecting the liveability of contemporary cities (Siirilä & Salonen,2024).

In particular, increasingly participative and co-creative nature-based solutions (NBS) are considered a fundamental approach for urban contexts to reverse the trend of natural resources’ depletion adversely affecting biodiversity, health and wellbeing, to the detriment of the most vulnerable in societies. As a result of this pressing situation calling for a broad spectrum of stakeholders to take responsibility for these crises across various governmental levels and territorial scales, public participation has taken on new significance, encouraging cooperation and co-creation towards alternative systems of production and consumption that restore ecological balance. According to this line of thought, the promise of co-creation and participation helps to identify opportunities to address specific needs and urban transformation imaginaries of various citizen segments and to match engagement strategies to cities’ participatory cultures (Nunes et al., 2024; Wamsler et al., 2020), emphasize the reconnection of people and nature (Kronenberg et al., 2024) with the ultimate scope of creating collaborative processes to develop more socially just cities.

However, co-creation and participatory approaches, with the novel interpretation of building better environmentally conscious solutions to achieve health and wellbeing, still entail the risks addressed in the seminal work on public participation (Arnstein, 1969). These include power imbalances reinforcing existing economic power structures as much as the risks of tokenism, co-optation and instrumentalization. Despite literature critically highlighting these and other pitfalls and limitations (Kiss et al., 2022), a growing depoliticised push from international institutions incentivising co-creative approaches for NBS in cities can be seen in many funded research projects (Mahmoud & Morello, E. 2021) including the one analysed in this paper, together with the designs of guidelines for effective co-creation with inclusive collaboration (Nunes et al., 2024). Yet, there is no one single participatory design that ensures delivery of better results in terms of inclusivity and sustainability (Dushkova & Haase, 2023). Ultimately, the question pertains to the effective potential of collaborative, environmentally sensitive methodologies for health and wellbeing to catalyse significant societal transformation, directly tangible at the urban scale (Leino & Puumala, 2021; Van Eijk, et al., 2023). Given the intricacy of the issues and variables involved, social transformation cannot be accomplished solely by the implementation of advanced participatory tools and procedures. Nevertheless, different participatory tools might be more effective than others in integrating public values into decision-making, facilitating dispute resolution, fostering trust among stakeholders, and ultimately inducing transformative change. In order to understand that, the paper analyses the design and adoption of participatory tools, in the process of co-creation for transnational learning in four small and medium size European cities, with the scope to get insights and knowledge on the cocreation engagement and the power dynamics affecting the democratic self-determination of stakeholders in newly established governance frameworks.

Supported by EU Horizon 2020 grant through the IN-HABIT project, the four cities are enabled to co-design solutions in four distinct fields, focussing namely on culture and heritage as a trigger to activate the neighbourhood in Cordoba (Spain); food to nurture daily healthier lifestyles in Riga (Latvia); human-animal bonds as a new relational urban value in Lucca (Italy); art, greening environment to reconnect places and people in Nitra (Slovakia), while addressing context-dependent vulnerable groups such as children, elderly, women, persons with disability, ethnic minorities and migrants. The scope of the co-creation participatory design was to expand the capacity of the project partners to engage stakeholders with a strong Gender, Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (GDEI) approach, and improve the polycentric governance towards Visionary Inclusive Solutions (VIS). The challenge was to design a coherent methodology able to set procedures and tools for all the different contextual situations, social ecosystems and articulated phases of the project.

This paper presents the main elements of the set of tools supporting the co-creation process, which were established at the inception of the IN-HABIT project and subsequently refined over the five-year implementation period. First, grounded in and elaborated upon the theory of co-production, the engagement framework of IN-HABIT draws from the work of Elinor Ostrom and her workshop at Indiana University (Ostrom 1990; Parks et al. 1981), which posits the essentiality of active beneficiary participation for the effective provision of services. A conceptual scheme for the coproduction process, termed Frame for Change (F4C), has been designed as a chart illustrating the essential components of a general transformational process (Tripodi, 2024). F4C is employed to map the distinctive features of each of the four projects and to structure them into a comparable format. Second, the participatory design required specific tools for engagement and for documenting the participatory process throughout the years. The tools adopted were inspired by knowledge exchange in transnational programs for European cities and programmes (Medeiros & Van der Zwet, 2020; Hurtado, 2024; Domínguez-González & Navarro Yáñez, 2023). Particular emphasis was placed on mapping the social ecosystems of stakeholders. The tools were designed to allow everyone access to participation but a specific attention has been devoted to vulnerable groups and individuals excluded, marginalised, usually left out in the decision making process of the localities of the project. Disenfranchised and vulnerable people are indeed the main beneficiaries of INHABIT and tools have been designed to facilitate their untapped capacities to achieve real impacts and future sustainability of the project. Third, INHABIT work has been inspired by the adoption of the Participated Integrated Sustainable Urban Development (SUD) approach. promoted by the EUCOM to assist cities and governing authorities in designing and implementing integrated urban strategies in accordance with the EU’s cohesion policy (Fioretti et al., 2020). This approach has guided the drafting and definition of the local action plans of the cities, through a self - assessment grid adopted to allow the monitoring of the project’s advancements. Fourth, to enhance the capabilities of local institutions to act in coproduction new local governance structures were established through stakeholder boards called IN-HUBs. The IN-HUB has the mandate of coordinating different participatory arenas with the scope of reaching consensus in designing and implementation of integrated local policies through local pacts and agreements. This required the design of a set of specific tools for drafting and sharing pacts, agreements in a transparent way. Fifth, a comprehensive tool called INHABIT Inclusive Transition Pathway (ITPath) was designed to overlook the participatory lay-out. It represents the parallel co-evolution of the four cities’ stakeholder ecosystem and the effects produced on the territories. The four ITPaths, one for each city, document both formal and informal agreements established during the process in a unified format.

In conclusion, while public participation and co-creation in urban planning have advanced significantly, their capacity to drive systemic societal transformation remains deeply contingent on context-specific factors. This paper demonstrates that the effectiveness of participatory tools is shaped by local dynamics, stakeholder engagement, and governance structures. By examining the IN-HABIT project’s participatory tools and approaches to monitor their adoption, the study offers critical insights into how tailored coproduction designs can foster inclusive health and wellbeing, highlighting both the progress made and the persistent challenges in realizing transformative urban change.

Frame for Change

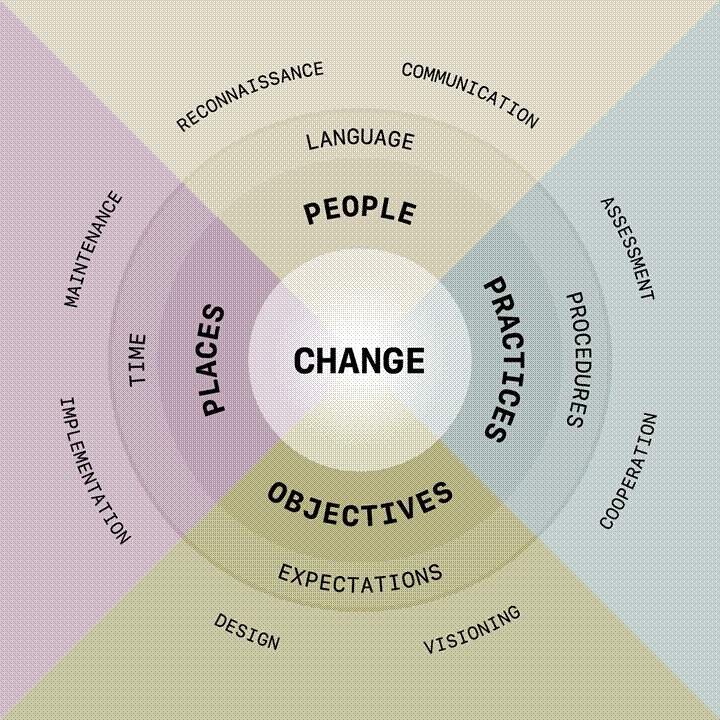

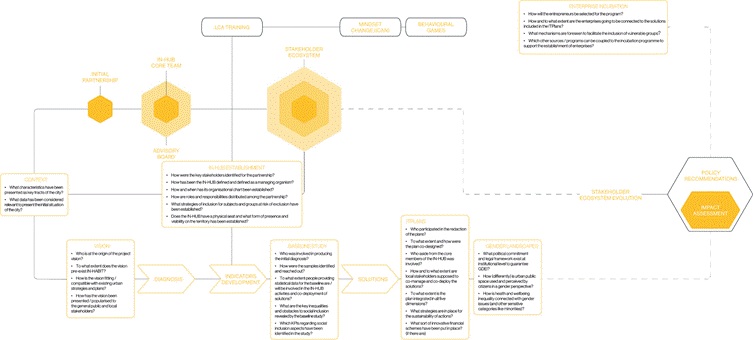

The IN-HABIT project started its co-creation path with defining a framework for stakeholder engagement named Frame4Change (F4C). The Theory of Change (Taplin & Clark 2012) posits that the process is directed towards the anticipated change (outputs) by examining the necessary preconditions to facilitate that change. The framework was designed to synthetically schematise the essential components of a generic transformative process, and puts at its centre the concept of change, around which are presented concentrically, in form of loops, three main analytical layers: the dimensions of transformation, the variables regulating the process, and the categories of action, as illustrated in figure 1.

1

Figure

1.

Frame4Change

Figure

1.

Frame4Change

Source:

Own elaboration.

The first category, identifying main fields of transformation, pertains to the primary phenomenological shift brought about by the process. Places relate to the spatial dimension, people to the social dimension, practices to the realm of production or the economies, objectives to the strategic or normative aspect. The premise is that every transformative process begins with a definite purpose: it may be focused on spatial development or on improving the welfare of a community, on promoting economic growth locally rather than modifying the planning instruments of a territory. Any transformative process engages to a certain extent with all these dimensions, but the original perspective triggering the initiative plays a crucial role in shaping the form and organisation of the process. For instance, architectural disciplinary perspectives may strongly influence the way in which we tackle an urban regeneration initiative, but we need to enquire how the solutions envisaged affect the local community, its economy and the planning and policy framework applied to that context; the same can be said from each original entry point we consider. The first loop of the Frame4Change enhances a reflection on how the initial disciplinary perspective from which a project is designed influences its impacts in other related fields, or its integration.

The second loop presents four key variables that determine the conditions to which the process needs to be adapted to achieve positive effects. The first factor is language, which encompasses aspects such as the natural languages used in the partnership (e.g., translating transnational projects and EU policies into local contexts, including minorities and migrant groups as beneficiaries or stakeholders), as well as the collision of different disciplinary languages and technical jargons within a large multidisciplinary partnership. Likewise, it involves translating policy and legal language from programmes, agreements, and contracts into easily comprehensible formulations for the public. Indeed, a crucial part of managing complex integrated projects is about translation, ensuring that the goal, agreements, and implementations of the initiative are easily understood and apparent to both partners and beneficiaries in a clear and open manner. Once a common language is set, we can move to assess or set the expectations. A comprehensive understanding of the expectations held by all stakeholders involved in the process is vital, especially when dealing with ambitious participatory procedures that require the involvement and support of citizens in a collaborative endeavour. Properly managing expectations and being prepared to reassess project objectives and procedures when the participants’ expectations change is crucial and should be considered throughout the entire process. The third essential variable is that of procedures, referring to the variety of methods by which “things are done”. This includes how responsibilities and tasks are distributed among the partners and how the partnership is established. Procedures play a crucial role in the framework by providing evidence to assess, analyse and report the engagement process. They are documented in official documents, contracts, and formal and informal agreements that are established and implemented throughout the effort. Finally, the fourth essential variable of the transformative process is time. The succession, interplay and dependencies of different activities and contributions determines critically the quality of the results, and the correct timing of singular actions makes them result in larger impacts than their sum. Time is of course the dimension that defines the processual nature of the project and is necessary to represent and evaluate its capacity to produce future impacts and its sustainability and permanence.

The third loop in the F4C scheme encompasses eight different types of activities required to advance the process. It starts ideally from reconnaissance, indicating the natural and direct process of understanding a socio-spatial situation through sensory experiences such as observation, spatial exploration, listening and reading. Communication involves the creation of guidelines, channels and codifications for sharing information about the project and its findings with partners, beneficiaries, and larger audiences. Assessment means the various actions that involve organising, systematising, evaluating and representing knowledge that has been created. This includes arranging data in formats that can be shared and made use of, such as databases, maps, surveys, baselines, evaluations, etc. Cooperation is about defining tasks, roles and procedures for the collaborative implementation of the project, including all management activities. Visioning refers to the activities aimed at imagining solutions, formulating hypotheses and outlining future scenarios. Design includes all the operations linked with developing ideas and plans into specific solutions necessary to generate the results of the project. Implementation regards the concrete execution of such ideas, plans and solutions into actual deliveries. Maintenance means the ongoing and long-term preservation of the project’s outcomes, both during and after its completion.

The circular shape implies a perfect cycle that starts with the initial reconnaissance and concludes with the maintenance of project outcomes. However, the causality of the phases in a transformative process is a lofty abstraction that does not align with reality. Activities occur simultaneously, irregularly intersecting and blending together. Any one of them can serve as the entry point in the process. Conversely, any of these action types can be analysed as a loop in itself, a trajectory that comes back to an initial point just be repeated and repeated again in order to advance the general process. The ability to go back and evaluate the outcomes of a single action, as well as its resonance with other elements of the process, develop reflexive practice, and act to improve synchronisation and synergy is critical. Consequently, the process of achieving the intended signifier “change” at the core of the scheme can be analysed in two ways: from the centre, where the anticipated change resides, one can navigate backward and in various directions through the primary domains of its expected effects—social, spatial, economic, or strategic—through the essential variables that the process must regulate—language, procedures, expectations, and time—ultimately arriving at the diverse activities necessary to guide the transformative process, which are here distilled into eight principal categories of action. Alternatively, the chart may be navigated in reverse, starting with a particular action, moment, or entrance point in the project’s implementation, progressing towards the overarching objective of achieving the intended change. Starting from the initial question formulated as “what change do we want / expect to realise?”, the goal of the chart is to facilitate the development of a comprehensive and logical set of questions related to the process we are involved in. This facilitates the adoption of a reflective methodology, allowing for ongoing learning, evaluation, and adaptation during multiple cycles, akin to “cognitive loops.”

Engaging the Stakeholders and Documenting the Participatory Process

To ensure the involvement of relevant parties in the project, IN-HABIT employs Local Community Activators into its process. The LCA is someone with expertise in the project’s target area, whilst serving as an animator and facilitator of local participatory processes. A Toolkit for Stakeholder Engagement including a Gender, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (GDEI) perspective has been designed to ensure a consistent fundamental understanding throughout all LCAs in different locations of IN-HABIT. This Toolkit serves as the foundation for the training of LCAs and provides the reference set for managing the four local IN-HUBs established in Córdoba, Lucca, Nitra, and Riga. Two tools have been particularly relevant to support the engagement process in this phase, namely the Stakeholder Maps and Engagement Diaries. Together with the self-assessment grid and the Co-management schemes (further explained in sections 3 and 4), the use of these tools enabled documenting the evolution of Public-Private-People Partnerships (PPPPs), assessing their capacity for co-designing and co-implementing solutions, as well as evaluating the formalisation and adaptability of each partnership.

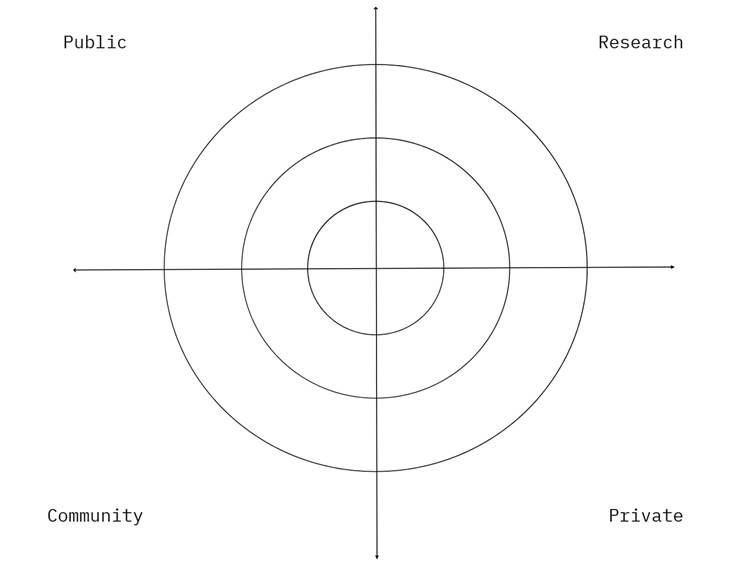

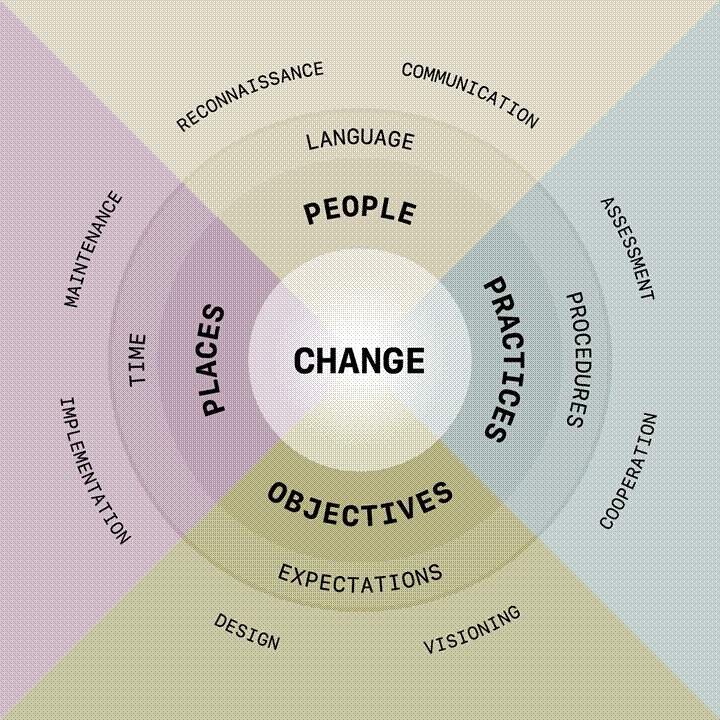

Stakeholder maps serve as a tool to facilitate the development and oversight of local PPPPs, monitoring the partnership’s progression throughout the project duration, and emphasising the engagement process of marginalised groups. The mapping serves to analyse stakeholders’ roles and interests, assess power relations within the social ecosystem, identify absent and vulnerable groups, and help formulate customised engagement strategies. The mapping process was designed making use of the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix models of innovation (Carayannis et al., 2013), categorising participants into public, private, research, and civil society sectors. These models emphasize balanced collaboration between different social actors (Quadruple Helix) while also considering the broader socio-environmental ecosystem (Quintuple Helix) (Figure 2).

Figure

2.

Stakeholder map template

Figure

2.

Stakeholder map template

Source:

Own elaboration.

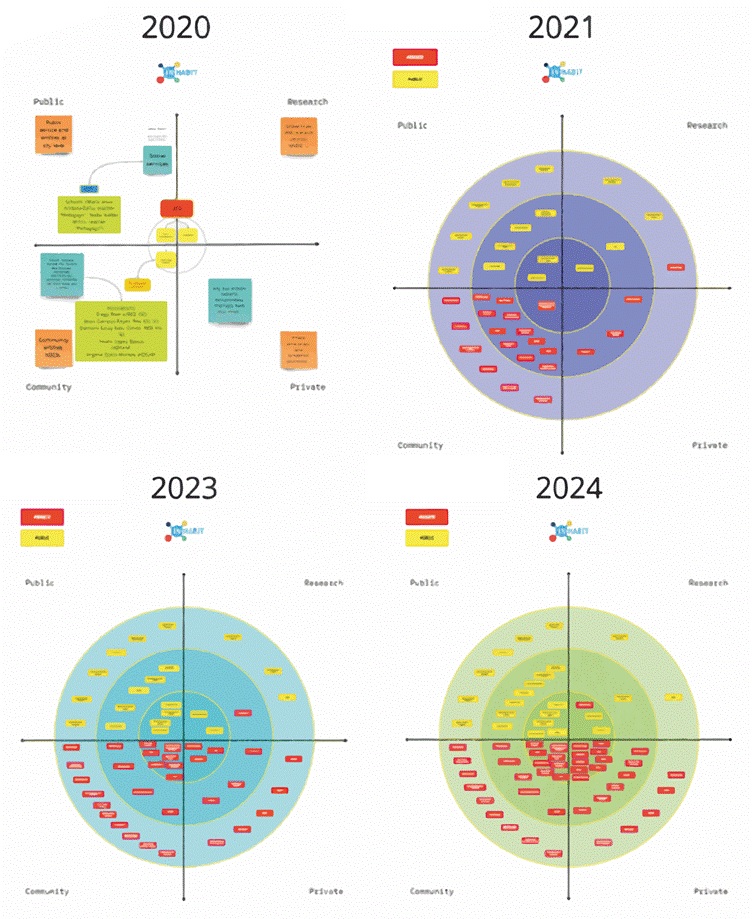

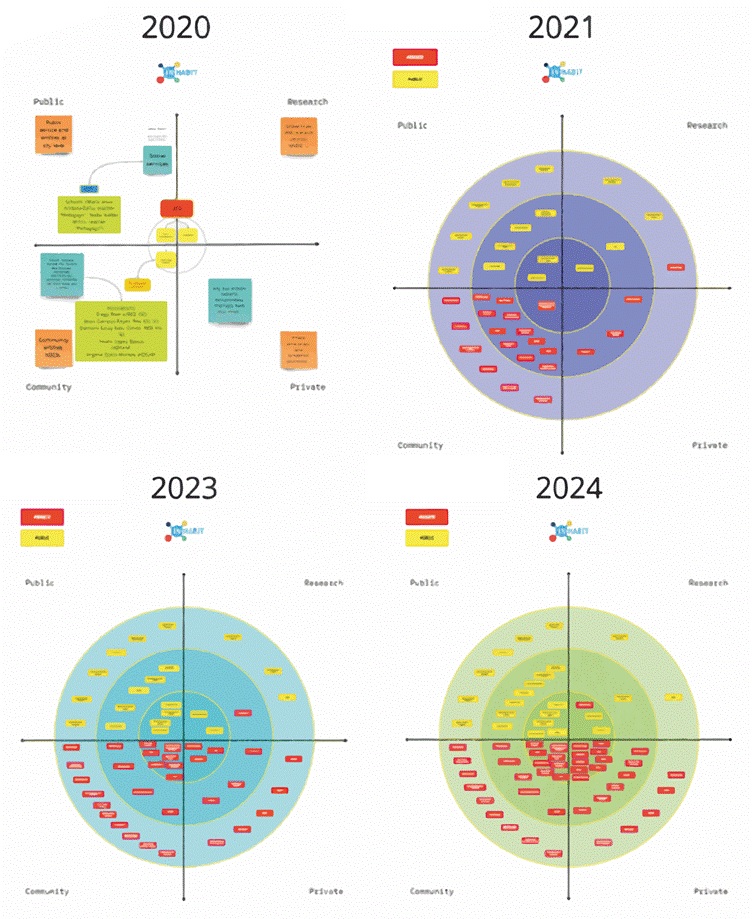

Figure 2 shows how the stakeholder map template employs a target diagram to locate actors according to four stakeholder typologies: public, research, community, and private. Stakeholders are placed in one of the four sectors based on how they operate (e.g., the statutory mission they declare) rather than how they are legally or informally established as subjects. The three concentric rings define four sectors which allow the positioning of stakeholders based on their level of engagement in the project. Typically, the core group of project partners steering the process is closest to the center. The second ring includes stakeholders directly engaged in or affected by the project (primary stakeholders). The external area is used either to map missing stakeholders that should/may be reached out for engagement or that act at a different territorial scale but may be relevant in the process (national institutions or transnational networks, global media, etc.). In IN-HABIT, the stakeholder map has been conceived as a living document, accessible via an online board and supplemented by a collaborative spreadsheet, that allows the continuous monitoring of the evolving stakeholders ecosystem in each of the four cities. The stakeholder mapping started with a targeted list of organisations and actors directly engaged in INHABIT and gradually expanded to include an extensive overview of the social innovation ecosystem in each city. Figure 3, for example, shows the evolution of this mapping process in the city of Córdoba.

Figure

3.

Stakeholder mapping evolution in Córdoba

Figure

3.

Stakeholder mapping evolution in Córdoba

Source:

Deliverable D1.3 of Córdoba - Monitoring and evaluation VIS for IHW in Cordoba. Midterm report. María del Mar Delgado-Serrano (UCO), Catalina Cruz-Piedrahita (UCO), Francisco-Javier Martínez-Carranza (UCO), 2024.

Stakeholder maps have played a fundamental role in identifying and visualizing all relevant forces involved—or expected to be involved—in the creation and management of local Public-Private-People Partnerships (PPPPs). One key insight from the stakeholder mapping process has been the push to move beyond broad categories (e.g., “businesses in the neighborhood”) and focus on specific individuals and groups within the intervention areas. A particularly valuable aspect has been unpacking the category of “community”. The PPPP model emphasises the engagement of “People” as active agents of change in the co-creation of solutions. This broad category includes both formalized and informal actors spanning multiple subgroups—some of which may be disconnected from one another or even in conflict. In some cases, there might not even exist a community recognised as such, but rather a set of individual neighbours and spontaneous assemblages whose participation can be nonetheless crucial to PPPP activities. In each case study, this has helped refine intervention strategies and establish indicators to assess the impact of actions in collaboration with local actors.

Stakeholder maps have been instrumental in visualizing how communities function—whether as cohesive groups with shared goals or as dispersed individuals with diverse needs, expectations, and capacities. Furthermore, they have helped identify tensions and conflicts within different sections of the PPPPs, offering crucial insights into their evolution.

However, stakeholder mapping has posed two significant challenges:

-

- Defining actor categories and

boundaries: classifying stakeholders and delineating their roles has proven

complex. Some public actors, for example, operate similarly to businesses,

while others, such as municipal social services, function more like civil

society actors. In other cases, the same organization can assume multiple roles

depending on the occasion which further complicates categorizing.

-

- Capturing stakeholder engagement

over time: stakeholder involvement has been highly dynamic, particularly during

the co-design phase, when interactions were more fluid and stakeholder maps

became more populated. However, during the co-implementation phase, engagement

often shifted toward bilateral or trilateral interactions mediated by LCA and

project partners. As a result, the stakeholder ecosystem became less dynamic,

though this shift was not always fully captured by the stakeholder map. In some

cases, participation declined rapidly, and stakeholder involvement in formal

platforms like user advisory boards or similar structures did not translate

into concrete actions.

To better delineate the scope and depth of stakeholder engagement, stakeholder maps should be complemented with additional data sources such as co-management scheme templates and engagement diaries, which provide a richer understanding of participation patterns and the evolving nature of partnerships.

Drawing on insights from the EU URBACT programme (URBACT, 2017), which trains cities in developing local plans through transnational exchange and mutual support, the Engagement Diaries (ED) further developed within IN-HABIT seek to provide a personalised, contextualised account of stakeholders’ engagement activities at the local level. The document challenges, solutions, inspirations, and innovative aspects of the engagement process among local stakeholders, while also promoting transnational exchange. Adopting a journalistic narrative format, EDs complement the impersonal reporting with a situated perspective derived from the personal experience of activators and managers doing fieldwork. Engagement Diaries derive from the consideration that managing a complex participative process as those foreseen by IN-HABIT requires a great capacity for developing personal relations and empathy. These aspects tend to be overlooked in conventional reporting forms, while EDs draw on personal narratives as an essential means of comprehension for the on-the-ground process. Local Community Activators had the autonomy to choose the format for their diary entries that best met their demands, including text, slide presentations, interviews, visual mind maps, short podcasts, or videos. The Engagement Diaries have been an essential tool for reconstructing the sequence of actions in the field and the intricate interactions unfolding within the stakeholder ecosystem. Nonetheless, analysing the data collected has posed issues owing to considerable heterogeneity in content and structure among cities. In many instances, journal entries were derived from field notes recorded during meetings and engagement activities, but in others, they constituted retrospective reports of specific obstacles encountered during project implementation. To facilitate comparison, a series of key queries derived from the Framework for Change were formulated, assisting in the assessment of critical action areas, variables, and key instances in the engagement process. This approach offered clearer insights into the different stages of the engagement process and improved data homogenisation, although it also reduced the personal, situated perspectives of local community activators. Consequently, Engagement Diaries evolved more into a systematic reporting tool rather than a narrative account of PPPP development. In the future, it may be beneficial to establish reporting protocols—such as field note guidelines and specific field recording techniques—that can be directly aligned with the key questions posed in the Engagement Diaries.

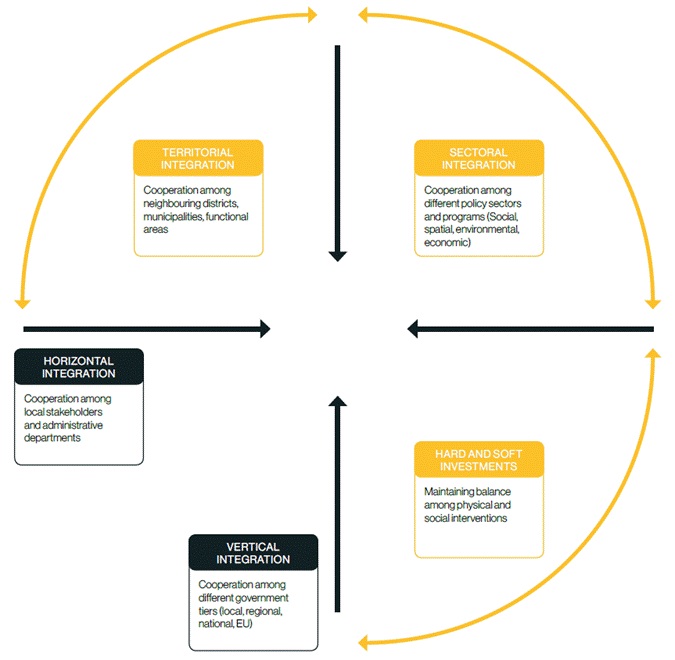

Self Monitoring: Integration Assessment Grid

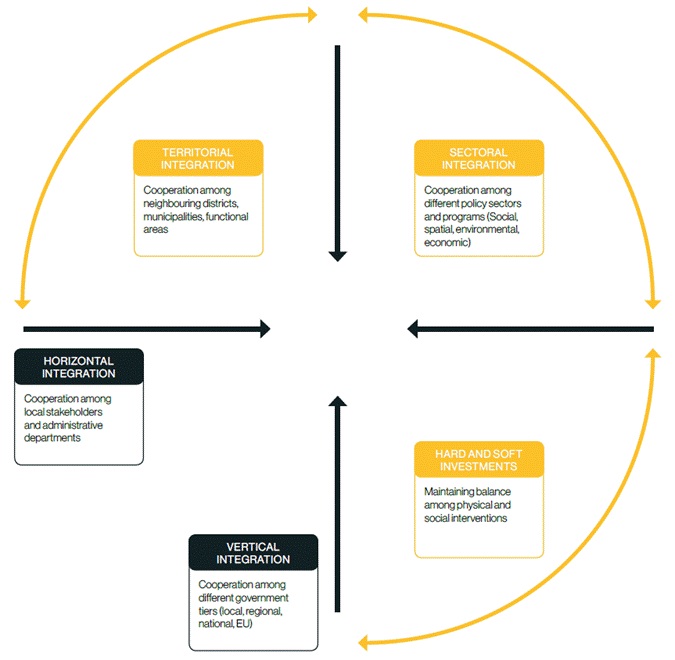

Along with the engagement process, a distinct tool to assess the collaboration of stakeholders for integrated policies was put in place to prevent the risks of isolated interventions, site-neutral approaches, and coordination-blind activities, which may yield only limited gains. (Faludi, 2009; Barca et al., 2012; Zaucha et al., 2012; Böhme & Redlich, 2023). Traditional urban planning approaches, such as rational planning, do not adequately integrate sustainability principles and show that to attain transformative change towards sustainable development, a coral and holistic approach to policy thinking, designing and implementation is advisable (Yigitcanlar & Teriman, 2014; Milojevic 2018). This approach, broadly referred to as “Integrated Approach” to Sustainable Urban Development calls for “multi-sectoral policy, multi-level and multi-stakeholder governance, and multi-territorial and community-led strategy” (Pertoldi et al., 2020). In practice, cities addressing sustainable urban development in their territories are asked to think about their interventions across a range of main “dimensions”. Figure 4 outlines five key dimensions of integration (Source: IN-HABIT Inclusive Transition Pathways).

-

Integration across the variety of

stakeholders involved in the territories and in the social and economic

ecosystems affected by the project locally (horizontal integration).

-

Integration across multiple scales

of intervention to incorporate the largest engagement of stakeholders,

including vulnerable groups across age, gender, income etc., at local, regional

and national levels (vertical dimension).

-

Integration across departments in

public administrations and policy areas (policy sector).

-

Integration across territorial

scales, considering impacts from districts and neighbourhoods

to wider territories and promoting a concerted and strategic vision of

development (territorial dimension).

-

Finally, the balanced integration

between hard interventions (physical development, i.e., European Regional

Development Fund - ERDF funded actions) and soft interventions (social type of

actions, i.e., European Social Fund - ESF funded action) can be considered as a

fifth dimension of integration.

While there is broad consensus on the strategic importance of an integrated planning approach, there is no single formula for achieving it. The implementation of integrated urban planning is inherently shaped by the context in which it is applied—including socio-economic conditions, legal frameworks, organizational and institutional support, and education.

Figure

4.

The five dimensions of integration. (Source: IN-HABIT D.5.2 Inclusive

Transition Pathways, 08-2022)

Figure

4.

The five dimensions of integration. (Source: IN-HABIT D.5.2 Inclusive

Transition Pathways, 08-2022)

Source:

Own elaboration.

In the context of IN-HABIT, the Integration Assessment Grid was proposed to help verify and self-assess the state of the art of the cities’ actions and their integrated approach in all five dimensions. Because of the nature of the partnership that IN-HABIT seeks to develop, each plan is integrated at different tiers, and activities must be synergically organised to achieve the plans’ objectives in practice. The Integration Assessment Grid enables the establishment of a common framework for comparing cities as well as keeping track of issues, solutions, inspirations, and innovative elements of the local stakeholder and community involvement process. Integration assessment exercises were carried out during city visits, with different degrees of participation. A major challenge was translating intricate technical jargon, notably European Commission terminology, into comprehensible language for local stakeholders. Moreover, convening key stakeholders at the same time proved a persistent difficulty throughout the partnership development process, and the integration assessment procedures were similarly affected. Nonetheless, the Integration Assessment Grid succeeded in creating a structured framework for discussion—going beyond the immediacy of delivering an action plan to reassess priorities, identify gaps, and clarify roles. It also assisted highlighting stakeholders who continued to work isolated. Figure 5 offers a glimpse into one of these exercises held in Nitra, capturing participants engaged in a real-time effort to navigate language, institutional roles, and expectations within a workshop setting.

Figure

5.

Integration Assessment Grid exercise in Nitra

Figure

5.

Integration Assessment Grid exercise in Nitra

Source:

Picture taken by the Nitra Team.

Partnership Agreements: Co-Management Scheme Template

Understanding the implementation of innovative decentralized governance models requires a thorough examination of the pacts and agreements developed during participatory processes. In this context, we employ the notion of co-management schemes, defined as “power sharing and participatory decision-making (formal or informal) arrangements among stakeholders such as inhabitants, governments, research institutions, private and non-governmental sectors”.

2

Specific co-management schemes templates have been designed to facilitate IN-HABIT partnerships. These documents are key to granting transparency in decision-making and the allocation of resources within participatory processes. They may also be regarded as the foundation upon which partnership is established. In the case of a formal agreement, a CMS defines clear boundaries of responsibility and liability, and in the case of an informal agreement it might delineate the flexible codes that underlie the collaboration. Similarly, the scale of the agreement recorded in the co-management scheme template is flexible: it can focus on individual actions/solutions, or it can refer to a whole plan. Moreover, co-management schemes have the purpose of supporting the development of forms of financial innovation, improving the sustainability of the solutions devised by the project, like in the case of social public procurement that includes green clauses and/or takes gender into consideration; community bartering, meaning the provision of voluntary work in return for non-monetary incentives such as educational and leisure opportunities, discounts on mobility services or food provision; or the promotion of business models around health and wellbeing together with residents and/or key stakeholders.

Co-management scheme templates have been adapted from primarily legal and business-oriented terminologies to emphasize the modes of cooperation that Public-Private-People Partnerships (PPPPs) can adopt. They are divided into 6 sections: (1) Agreement description; (2) transformative dimensions; (3) partnership for co-production; (4) resources; (5) clauses/rights and caveats, and (6) schedule. The first section describes the type of agreement, defines the collaboration’s scope, and explains why the pact is necessary or innovative. The second section draws directly from the four dimensions of change outlined in the Framework for Change: spatial, strategic, social, and economic dimensions, explaining the main type of change the agreement aims to achieve. The third section regards the partners, the distribution of tasks and roles, as well as the responsibilities, liabilities and conflict resolution mechanisms. The fourth section pertains to funding and other types of resources at the disposal of the partnership, such as voluntary work or in-kind contributions. The fifth section contains clauses for revision and performance, which, for example, could include gender-responsive clauses in social public procurement. This section also provides space to clarify intellectual property and copyright matters. The sixth and final section outlines the collaboration’s calendar, including milestones and deliveries.

The template can be employed as a tool to guide the design of co-management schemes, as well as their documentation and analysis ex-post. Its purpose is inherently functional, and the categories outlined above should be seen as a flexible framework rather than a rigid checklist. Similarly to the Integration Assessment Grid, co-management scheme templates have faced challenges in ensuring transparency in the implementation of plans. Existing legal frameworks frequently conflict with the strict interpretations and operating protocols of institutions in practice. In some cases, political representatives and public servants did not function as a single entity, further complicating the process. Some agreements took months or even years to finalize, delaying formal reporting until contracts, leases, and different legal documents were signed, which in turn hindered transparency. Local elections also significantly impacted these processes, affecting and changing institutional procedures during the project’s lifespan. In some cases, national laws imposed rigid frameworks for agreements, and institutions lacked the expertise to develop procurement guidelines that aligned with the project’s needs. All these factors forced partners to develop a very flexible and fluctuating approach to create agreements that were not always easily translated into a co-management scheme template.

A crucial insight gained from the analysis of co-management schemes has been the importance of identifying the specific needs each scheme addresses. Whether the goal is to formalize an unconventional partnership, resolve a concrete problem, or update an outdated agreement, making these distinctions explicit has been essential for providing clarity to the engagement process and enabling comparative analysis across cities.

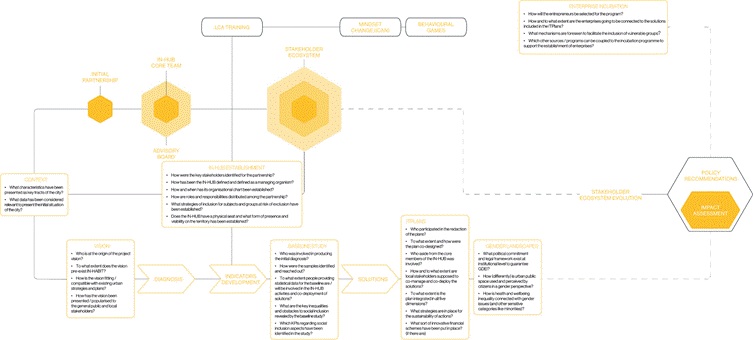

Co-Designing and Co-Implementing Solutions: ITPath

Data and narratives collected through the above-presented instruments converged into the Inclusive Transition Pathways (ITPaths), a delivery required to document and analyze the overall stakeholder engagement process of each city. Transition Pathways are a concept used to think about change in a systemic perspective. In academic and policy work, Transition Pathways are a framework for thinking about how change happens in economic terms. Pathways help outline the timing, scope, and scale of change necessary throughout the whole landscape for a region, industry, or economy to get from Point A to Point B, namely, to transition from a current state of things to a desired one (McNally, 2021). Transition Pathways are not plans, nor strategies. Pathways complement the strategy, assessing whether some solutions or ideas will be effective in getting from A to B and identifying what factors need to be considered or addressed to achieve a particular goal. Transition Pathways look at how some ideas and specific solutions can work in changing the world we live in. Transition pathways are a useful framework for decision-makers because they can help outline how each of these ideas might influence the way change happens at a system-level. The term Transition Pathway emerged in recent years particularly in connection with environmental issues (Droege, 2011) and sustainable cities (Nevens et al., 2013; Grossmann & Creamer, 2017; Zhang et al., 2018; Crowley et al., 2021). In particular they are developed to represent paradigmatic transitions towards low carbon models of production and consumption as a response to the climate change crisis. The environmental sustainability objective, as a matter of fact, is deeply connected with the engagement aspect, highlighting how only transitions models based on wide participation and the responsibilisation of all the social components and economic actors may succeed (Marat-Mendes et al., 2022) This is for instance the approach of the transition movement, born in the early 2000 around the notion of transition towns, leading to the establishment of the Transition Network in 2006 to inspire, encourage, connect, support communities on their transition (Connors & McDonald, 2011). This grassroots movement aims at effectively developing a low carbon model responding to peak oil and climate change through an incremental grassroots strategy steered by local communities. Transition towns are connected in a network and share a roadmap for a low carbon future to be implemented through a polycentric governance model.

With a similar scope, Inclusive Transition Pathways in INHABIT create a shared roadmap towards Health and Well-being in the four cities. Combining both the storyline and the documentary record (protocols and agreements) to report and visualize the engagement process, the ITPath is designed to foster the inclusion aspect of the IN-HABIT project’s overall strategy and to guide the development of a polycentric governance model in the four cities. Complementing the delivery of the four Integrated Transformation Plans (ITPlans), with their set of Visionary Integrated Solutions (VIS) for each city, the Inclusive Transition Pathways retrace actions, procedures and agreements created among the stakeholders to make them happen. According to the definition in the grant agreement, the four Inclusive Transition Pathways should be the basis of the innovative governance mechanisms that each city will test. Moreover, the ITPaths contribute to the delivery of the final Policy Recommendations. The three key features leading to the elaboration of the Inclusive Transition Pathway were derived from the literal interpretation of its name:

-

It is a pathway, in the sense that

it visualizes the journey from the initial moment of the project to the final

situation foreseen at its end, recording its key operational moments and

milestones.

-

It regards the expected transition

towards a more innovative, polycentric and sustainable governance model,

documenting agreements, pacts and protocols created along the process.

-

It

is inclusive, as it aims at supporting and measuring the larger engagement of

stakeholders in the process, with specific attention to gender, diversity,

equity and inclusion (GDEI).

The IN-HABIT ITPath is a scheme representing in a synthetic form two intertwined components of the process: on one side the evolution of the local partnership and its active positioning within the local social ecosystem; on the other, the field activity produced through the co-design, co-deployment and co-monitoring of solutions in the given territories. It identifies a set of key moments, each one of them accompanied by a set of key questions to record the engagement process and support its improvement in terms of inclusivity, integration and governance. These questions—presented in figure 6—form the backbone of the Inclusive Transition framework, enabling structured reflection on how partnerships evolve and how decisions are made and implemented across the project cycle. The ITPath documents the evolution of the partnership including adopted formal and informal protocols and signed contracts, which may assume very different forms such as employment and procurement contracts, memoranda of understanding, collaboration pacts, charters and manifestos, etc.

Figure

6.

Inclusive Transition Framework: key questions (authors’ elaboration)

Figure

6.

Inclusive Transition Framework: key questions (authors’ elaboration)

Source:

Own elaboration.

The ITPaths first delivery happened after the first two years of the project. Combined in a single report, they included a diagnostic section, documenting the process of establishing a common vision for local health and wellbeing, and detailing objectives and partnership agreements for its achievement; and a prognostic section, conceived as a road map for the co-deployment and co-monitoring of the solutions, with the focus on the establishment of innovative polycentric governance schemes. They have been reviewed after 18 months to include the first comparative reflections on the formation of the partnerships and are now leading the elaboration of the final policy recommendations.

Conclusions

This paper presents the adoption of stakeholder engagement tools across four distinct contexts, supporting the development of Public-Private-People Partnerships (PPPPs) within the IN-HABIT project. Drawing on initial reflections from a comparative analysis of the Inclusive Transition Pathways (ITPaths), these tools proved essential in several respects: disentangling the complexity of processes unfolding in each context through visualization of their constituent elements and phases; depicting local social ecosystems not merely as static backdrops but as evolving stakeholder constellations mobilized by the project; fostering agency, capacity building, and leadership necessary for transitions toward distributed governance models; and facilitating a “learning by doing” approach that enabled rapid extraction of lessons learned and promoted adaptive knowledge exchange among partners. While IN-HABIT developed a comprehensive framework encompassing stakeholder engagement, participatory documentation, and integrated assessment, the practical implementation of these methodologies revealed significant complexities that challenge the idealized, linear models often portrayed in the literature.

The circular conceptualization of transformative processes ‒which implies a seamless progression from reconnaissance to maintenance‒ fails to capture the inherently non-linear, iterative, and frequently chaotic nature of urban change. In practice, project activities intersect, overlap, and recur unpredictably, complicating attempts to delineate clear causal relationships or discrete entry points within the process. This observation problematizes the utility of rigid, phase-based models for guiding real-world interventions and instead advocates for more adaptive, reflexive frameworks capable of accommodating the dynamic interplay among actors, actions, and contexts.

A primary objective of IN-HABIT’s toolkit was to support a holistic understanding and shared management of complex processes, responding to the imperative for sustainable and integrated urban projects. Complexity manifested across multiple dimensions: the diverse territorial identities, scales of intervention, policy frameworks, and social ecosystems implicated in the four projects; as well as the multifaceted concept of inclusive health and wellbeing, which encompasses varied factors, agencies, and indicators. The toolkit emphasized visualization as a critical technique for mastering processual complexity, cultivating systemic thinking, and designing co-created interventions. Both the F4C and ITPaths schemes highlighted the importance of tracking associations as dynamic phenomena, focusing on relational assemblages rather than reified social components (Latour 2005). Concurrently, these tools facilitated critical reflection and real-time comparison of divergent partnership trajectories.

Despite the indispensable role of participatory tools in elucidating process intricacies, methods and procedures alone are insufficient to drive social transformation or ensure the long-term adoption of innovative governance models. The thorough analysis of IN-HABIT’s engagement processes illuminated the positive effects of such tools in fostering broader and deeper stakeholder responsibilization. However, it also exposed the fragility of governance architectures established through isolated projects, particularly when participatory culture is not well-rooted locally or when leading stakeholders lack experience or political will in synergistic territorial governance. A paradigmatic finding was the influence of the leading stakeholders’ institutional nature and form within each PPPP on the capacity of engagement processes to generate collaborative environments.

The stakeholder mapping and engagement tools, grounded in the Quadruple and Quintuple Helix models, were instrumental in visualizing and managing the evolving PPPP ecosystems. Nevertheless, categorizing stakeholders and capturing their shifting roles over time proved problematic. The fluidity of actor identities -whereby public entities may function alternately as entrepreneurs or civil society actors depending on context- undermines the stability of stakeholder categories and complicates analyses of power relations and engagement strategies. Moreover, the observed decline in stakeholder participation during later project phases, coupled with the limited translation of formal engagement into concrete action, underscores persistent challenges in sustaining meaningful involvement, especially among marginalized groups.

The Engagement Diaries, designed to provide nuanced, context-rich accounts of participatory processes, confronted issues of heterogeneity and comparability. Over time, they evolved toward more standardized reporting formats, sacrificing personal narrative depth. This shift raises concerns about the erosion of situated knowledge and the privileging of procedural uniformity over the rich experiential insights that underpin authentic co-creation and collective learning.

Similarly, the Integration Assessment Grid, while valuable for promoting structured reflection and facilitating cross-city comparison, encountered obstacles related to technical language barriers and was not utilised as initially foreseen. These challenges resonate with broader critiques in the literature regarding integrated planning approaches (Galego et al., 2004; Medeiros & Van der Zwet, 2020) which, despite their strategic appeal, often falter amid contextual constraints, institutional inertia, and entrenched siloed practices.

In sum, the IN-HABIT experience underscores the imperative to transcend prescriptive models and embrace more flexible, context-sensitive methodologies that acknowledge the messy, contested, and emergent character of urban transformation. Future research and practice should prioritize the development of tools that not only facilitate monitoring and evaluation but also foster critical reflexivity, adaptive learning, and genuine empowerment among all stakeholders-particularly those whose voices are frequently marginalized in formal processes.

References

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A Ladder of Citizen Participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216-224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

Barca, F., McCann, P., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2012). The Case for Regional Development Intervention: Place-Based versus Place-Neutral Approaches. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 134-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

Böhme, K., & Redlich, S. (2023). The Territorial Agenda 2030 for Places and a More Cohesive European Territory? Planning Practice & Research, 38(5), 729-747. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2023.2258029

Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2013). Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems: Quintuple Helix and Social Ecology. In E. G. Carayannis (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (pp 1293-1300). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3858-8_310

Charland, S. (2024). Public Engagement Made Easy: A Guide for Planners and Policymakers. Taylor & Francis.

Connors, P., & McDonald, P. (2011). Transitioning Communities: Community, Participation and the Transition Town Movement. Community Development Journal, 46(4), 558-572. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44258308

Crowley, D., Marat-Mendes, T., Falanga, R., Henfrey, T., & Penha-Lopes, G. (2021). Towards a Necessary Regenerative Urban Planning: Insights from Community-Led Initiatives for Ecocity Transformation. Cidades, Comunidades e Territórios, 83-104 https://doi.org/10.15847/cct.20505

Domínguez-González, A., & Navarro Yáñez, C. J. (2023). The Impact of EU-Integrated Urban Development Initiatives: Research Strategies beyond ‘Good Practices’. In EU Integrated Urban Initiatives: Policy Learning and Quality of life impacts in Spain (pp. 111-130). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-20885-0_7

Dushkova, D., & Haase, D. (2023). Resilient Cities, Healthy Communities, and Sustainable Future: How Do Nature-Based Solutions Contribute? In Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health (pp. 1-24). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-25110-8_133

Droege, P. (2011). Urban Energy Transition: From Fossil Fuels to Renewable Power. Elsevier.

Faludi, A. (2009). A Turning Point in the Development of European Spatial Planning? The ‘Territorial Agenda of the European Union’ and the ‘First Action Programme’. Progress in Planning, 71(1), 1-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2008.09.001

Fioretti, C., Pertoldi, M., Busti, M., & Van Heerden, S. (2020). Handbook of Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (No. JRC118841). Joint Research Centre.

Galego, D., Esposito, G., & Crutzen, N. (2024). Sustainable Urban Development: A Scoping Review of Barriers to the Public Policy and Administration. Public Policy and Administration, 0(0), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/09520767241266410

Grossmann, M., & Creamer, E. (2017). Assessing Diversity and Inclusivity within the Transition Movement: An Urban Case Study. Environmental Politics, 26(1), 161-182. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2016.1232522

Hofer, K., & Kaufmann, D. (2023). Actors, Arenas and Aims: A Conceptual Framework for Public Participation. Planning Theory, 22(4), 357-379. https://doi.org/10.1177/14730952221139587

Hurtado, S. D. G. (2024). The Regeneration of Urban Vulnerable Neighbourhoods: An EU Policy that Matters? In Urban regeneration in Europe (pp. 267-291). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-64773-4_11

Kiss, B., Sekulova, F., Hörschelmann, K., Salk, C. F., Takahashi, W., & Wamsler, C. (2022). Citizen Participation in the Governance of Nature-Based Solutions. Environmental Policy and Governance, 32(3), 247-272. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1987

Kronenberg, J., Andersson, E., Elmqvist, T., Łaszkiewicz, E., Xue, J., & Khmara, Y. (2024). Cities, Planetary Boundaries, and Degrowth. The Lancet Planetary Health, 8(4), e234-e241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00025-1

Lane, M. B. (2005). Public Participation in Planning: An Intellectual History. Australian Geographer, 36(3), 283-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049180500325694

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford University Press.

Leino, H., & Puumala, E. (2021). What Can Co-Creation Do for the Citizens? Applying Co-Creation for the Promotion of Participation in Cities. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 39(4), 781-799. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420957337

Mahmoud, I., & Morello, E. (2021). Co-Creation Pathway for Urban Nature-Based Solutions: Testing a Shared-Governance Approach in Three Cities and Nine Action Labs. In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions: Results of SSPCR 2019—Open Access Contributions 3 (pp. 259-276). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57764-3_17

Marat-Mendes, T., d’Almeida, P. B., & Borges, J. C. (2022). Concepts and Definitions for a Sustainable Planning Transition: Lessons from Moments of Change. European Planning Studies, 30(8), 1421-1443. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1894095

McNally, J. (2021, January 29). What is a Pathway? A Conceptual Overview of Transition Pathways. Energy Futures Lab. https://energyfutureslab.com/what-is-a-pathway-a-conceptual-overview-of-transition-pathways/

Medeiros, E., & van der Zwet, A. (2020). Sustainable and Integrated Urban Planning and Governance in Metropolitan and Medium-Sized Cities. Sustainability, 12(15), 5976. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155976

Milojevic, B. (2018). Integrated urban planning in theory and practice. САВРЕМЕНА ТЕОРИЈА И ПРАКСА У ГРАДИТЕЉСТВУ, 13.

https://doi.org/10.7251/STP1813323M

Nevens, F., Frantzeskaki, N., Gorissen, L., & Loorbach, D. (2013). Urban Transition Labs: Co-Creating Transformative Action for Sustainable Cities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 50, 111-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.001

Nunes, N., Hilding-Hamann, K. E., & Ferreira, I. (2024). Co-creation of Nature-Based Solutions: Guidelines for Citizen Engagement. In Social Work and Social Innovation: Emerging Trends and Challenges for Practice, Policy and Education in Europe (p. 208). https://doi.org/10.3390/su132313378

Ostrom, E. (1990). Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press.

Parks, R. B., Baker, P. C., Kiser, L., Oakerson, R., Ostrom, E., Ostrom, V., Percy, S. L., Vandivort, M. B., Whitaker, G. P., & Wilson, R. (1981). Consumers as Coproducers of Public Services: Some Economic and Institutional Considerations. Policy Studies Journal, 9(7), 1001-1011. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.1981.tb01208.x

Pertoldi, M., Fioretti, C., Guzzo, F., Testori, G., De Bruijn, M., Ferry, M., Kah, S., Servillo, L. A., & Windisch, S. (2020). Handbook of Territorial and Local Development

Siirilä, J.,

& Salonen, A. O. (2024). Towards

a Sustainable Future in the Age of Polycrisis. Frontiers in Sustainability, 5,

1436740.

Taplin, D., & Clark, H. (2012). Theory of Change Basics: A Primer on Theory of Change. ActKnowledge.

Tripodi, L. (2024). Loops of Change. Lo Squaderno, 68, 57-60

URBACT. (2017). URBACT Toolbox: A Set of Tools and Resources to Help You Shape Better Cities. Author. https://urbact.eu/toolbox-home

Van Eijk, C., Van der Vlegel-Brouwer, W., & Bussemaker, J. (2023). Healthy and Happy Citizens: The Opportunities and Challenges of co-Producing Citizens’ Health and Well-Being in Vulnerable Neighbourhoods. Administrative Sciences, 13(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13020046

Voorberg, W. H., Bekkers, V. J. J. M., & Tummers, L. G. (2014). A Systematic Review of Co-Creation and co-Production: Embarking on the Social Innovation Journey. Public Management Review, 17(9), 1333-1357. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2014.930505

Wamsler, C., Alkan-Olsson, J., Björn, H., Falck, H., Hanson, H., Oskarsson, T., Simonsson, E., & Zelmerlow, F. (2020). Beyond Participation: When Citizen Engagement Leads to Undesirable Outcomes for Nature-Based Solutions and Climate Change Adaptation. Climatic Change, 158(2), 235-254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-019-02557-9

Yigitcanlar, T., & Teriman, S. (2014). Rethinking Sustainable Urban Development: Towards an Integrated Planning and Development Process. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, 12(1), 341-352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13762-013-0491-x

Zaucha, J., Komornicki, T., Böhme, K., Świątek, D., & Żuber, P. (2012). Territorial Keys for Bringing Closer the Territorial Agenda of the EU and Europe 2020. European Planning Studies, 22(2), 246-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722976

Zhang, X., Bayulken, B., Skitmore, M., Lu, W., & Huisingh, D. (2018). Sustainable Urban Transformations Towards Smarter, Healthier Cities: Theories, Agendas and Pathways. Journal of Cleaner Production, 173, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.10.345

Notes

*

Artículo de

investigación / Research article

1

While the differences between the two terms change and

transformation are disputed (Voorberg et al., 2014), here the term change is understood as significantly different from that of transformation. While the transformation is

approached as an inevitable, ontological condition that inescapably affects

physical reality, change implies the determination to produce positive

transformations envisioned and agreed upon with and within the affected communities

2

From the IN-HABIT H2020 project grant agreement.

Author notes

a Autor de

correspondencia / Correspondence author. E-mail: lorenzo@tesserae.eu

Origin of this Research

This research has been funded under the IN-HABIT (Incluside Health and Well-being in Small and Medium-sized Cities) project as a part of the Horizon 2020 Program (Grant Agreement No. 869227). The contents of this document do not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. The responsibility for information and opinions expressed herein lies solely with the authors.

Additional information

Cómo citar / How

to cite: Tripodi, L., Colini, L., & Benavides, L. M. (2025).

Coproduction

for Change: Participatory Tools for Inclusive Health and Wellbeing in European

Small and Medium Size Cities. Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 18. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.cvu18.ccpt