Introduction

Phosphorus is a mineral present in every cell of an organism. Most phosphorus is found in the bones and teeth, with a smaller portion located in genetic material. Organisms need phosphorus to produce energy and to carry out essential chemical processes [1]. It is also a vital nutrient for both plants and animals. The appropriate and efficient use of phosphate rock as a phosphorus source can help strengthen sustainable agricultural practices in developing countries, particularly those with phosphate rock deposits [2].

The term phosphate rock (or phosphorite) refers to any geological material with a high concentration of phosphorus. The most abundant and cost-effective source of phosphorus is obtained through mining and beneficiation of phosphate rock from deposits worldwide [3]. Phosphate rock (PR) is a valuable mineral resource with a wide range of agricultural and environmental applications. It is used in the production of detergents, animal feed, and phosphate (P) fertilizers. While the direct application of PR reduces pollution by serving as a slow-release fertilizer, its effectiveness is constrained by several factors. The primary limitation of direct PR use is its low solubility, which reduces its availability for soil reactions and plant uptake [4].

In 2023, global phosphate rock (PR) production reached 220 million metric tons [5]. Of this total, 41% was concentrated in China, followed by Morocco (16%), the USA (9%), Russia (6%), and Jordan (5%). Together, these countries accounted for 77% of global PR mining [6]. On the American continent, Colombia ranked as the fifth-largest producer, after the USA, Brazil, Peru, and Mexico, with an annual output exceeding 65,000 tons [7]. The average value of phosphate rock in 2023 was USD 147.32 per metric ton (f.o.b. mine), representing an 8.3% increase compared to the 2022 average of USD 136.00 per ton [8][9].

The acidulation of phosphate rock is a hydrometallurgical process used to produce phosphoric acid [10][11], a key intermediate in fertilizer production [12][13]. In Colombia, 75% of the phosphate rock extracted is directed to phosphoric acid production [12]. During this process, various acids—including sulfuric, nitric, and hydrochloric—can be used to obtain P-rich solutions [10][11]. However, due to the composition of phosphate rock, the leaching process also dissolves impurities such as Ca compounds, thereby releasing both P and Ca ions into the resulting solution [15].

Regarding the thermodynamics of phosphate rock processing and the formation of calcium phosphate, several studies stand out. In 2004, one study examined brushite, a crystalline hydrated calcium phosphate, to better understand the crystal growth mechanism and the mineralization behavior of calcium phosphate compounds. This analysis was carried out using a quantum mechanical model [16]. Later, in 2008, another study investigated the relationship between hydroxyapatite and mullite extraction processes, focusing on the stability of different stages and the development of structures. Based on chemical and morphological characterization, the study discussed the sintering reactions that occurred [17].

In 2013, the decomposition of apatite into tricalcium phosphates made it possible to better understand the synthesis, sintering, and mechanical properties of the hydroxyapatite phase. This, in turn, facilitated further studies evaluating the applicability of sintering techniques to apatite-containing varieties [18]. That same year, monetite was obtained from the decomposition of brushite through sonication tests, where ultrasonic energy was applied to induce and accelerate reactions. The study showed that phase transformations can be achieved using sonication and that such transformations involve changes at the single-cell level of the material [19].

In 2008, different calcium sources were used to synthesize various calcium phosphate compounds. The study concluded that natural sources were more economical due to the abundance of ores. Within this framework, the CaCO.–H.O– P.O. ternary system was investigated to determine stability zones for hydroxyapatite and other phases at temperatures of 70 °C [20].

In 2020, thermodynamic models were developed for several processes aimed at enriching phosphorus and calcium solutions. One example involved evaporating chemical phosphorus species under controlled atmospheric conditions to evaluate phosphate layer formation and predict surface modifications. These experiments led to the production of hydroxyapatite, tricalcium phosphate, and other phases [21].

Most recently, in 2024, thermodynamic models were used to prepare highly pure tricalcium phosphate powders via solid-state synthesis. The models guided experimental determination of the optimal synthesis temperature, established at 1000 °C. Notably, this synthesis route improves the quality of the products generated [22].

A review of the available literature shows that relatively few studies have successfully addressed the relationship between thermodynamics and the stability of aqueous systems involved in phosphate mineral decomposition. In light of this gap, the objective of the present study is to evaluate the behavior and stability of the phases obtained through hydrometallurgical treatment of phosphate rock. The aim is to generate chemical stability diagrams that define operational ranges for producing phosphate compounds, which may subsequently be applied in fertilizers and potentially in biomaterials.

Materials and Methods

Materials and Characterization

Ore samples were collected from a phosphate rock (PR) mining company located in the Department of Boyacá, Colombia, and were subsequently crushed and ground to a particle size of less than 103 µm. These samples were chemically and mineralogically characterized using an Epsilon 13V 1.5 Malvern Panalytical X-ray fluorescence spectrometer and a Panalytical X’Pert Pro MPD X-ray diffractometer, respectively. For XRD analysis, the operating conditions were set to scan the 2θ axis from 5° to 70° with a step size of 0.02° and a counting time of 0.5 s per step, employing Cu Kα radiation with a wavelength -λ- of 1.5406 Å, while the X'pert High Score Plus software was used for data processing.

Leaching Tests

The objective of phosphate rock (PR) leaching is to obtain solutions with a predominant presence of phosphate (PO4)-3 and calcium (Ca2+) ions. For this purpose, the PR sample was subjected to laboratory-scale leaching in nitric acid (HNO3) solutions at concentrations of 2, 3, 4, and 5 M for 24 h, to analyze the dissolution behavior of P and Ca as a function of acid concentration. The process was carried out in beakers with mechanical agitation at a fixed speed, maintaining a constant solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:3. The concentrations of P and Ca in the resulting acid leach solutions were analyzed using semiquantitative XRF characterization.

Variety, Precipitation, and Characterization

The solutions containing P and Ca ions were separated by filtration and used as raw materials for this study. A volume of 10 mL from the acid leaching solutions (4 M HNO3) was transferred to a beaker under constant magnetic agitation and reacted with a 0.5 M NaOH solution to adjust the pH to three target values: 3, 5, and 10, measured with an Apera Instruments Premium Series PH8500-SA pH meter. Once the desired pH was reached, agitation was stopped, and from each pH condition, three solid precipitates were obtained. The solids were washed to remove soluble residues and dried on heating plates at 100 °C. Each precipitate was then analyzed by XRD using a Panalytical X’Pert Pro MPD diffractometer, and by SEM using a JEOL JSM-5910LV microscope.

Results

Elemental and Mineralogical Composition of the PR Sample

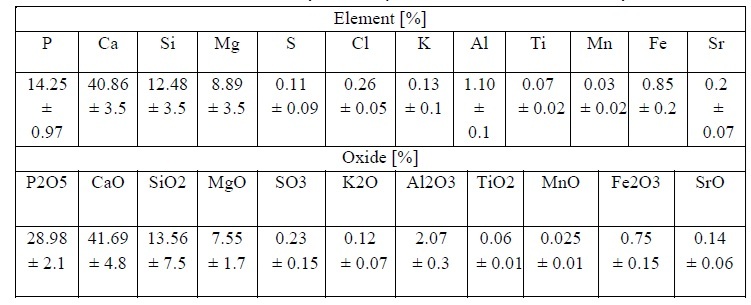

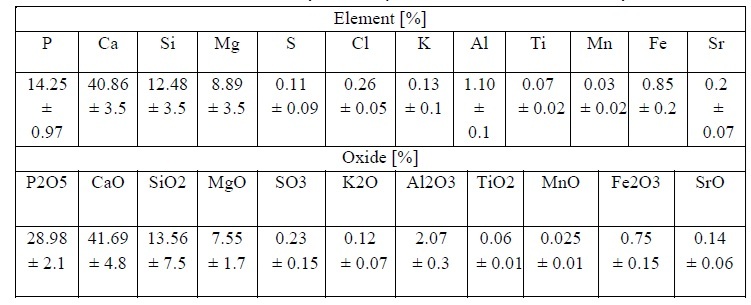

Table 1 presents the XRF results for the elemental composition of the phosphate rock (PR) mineral samples. The analysis indicates that the major elements in PR are Ca, P, Si, and Mg; however, the XRF software also provides a quantitative assessment expressed as oxides derived from these metals, which are likewise reported in Table 1. Both the elemental concentrations and the corresponding oxide values fall within the ranges reported by other researchers for PR minerals worldwide [23][24].

Table 1.

Elemental

chemical composition analysis and stoichiometric oxides in the PR sample

Source: Author.

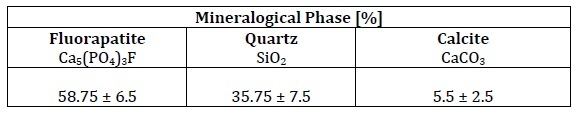

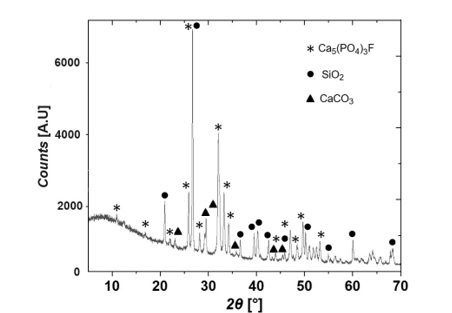

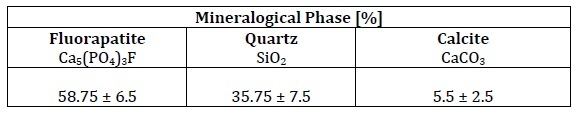

Table 2 presents the quantification of the predominant mineral phases identified in the phosphate rock (PR) samples, with fluorapatite accounting for an average of more than 58%. Figure 1 shows a diffractogram highlighting the main peaks of the predominant minerals present in a PR sample: fluorapatite, quartz, and calcite. Based on the identified patterns, the following characteristic positions and planes were determined: 31.94(4)° (2 1 1) for fluorapatite (⁕), 26.64(6)° (0 1 1) for quartz (●), and 29.45(2)° (1 0 4) for calcite (▲). The principal peaks of the fluorapatite phase are consistent with results reported in previous studies [24][25].

Table 2.

Mineralogical phases present in the PR samples

Source: Author.

Figure 1.

X-ray

Diffraction Diagram of a Sample of PR

Figure 1.

X-ray

Diffraction Diagram of a Sample of PR

Source: Author.

Leaching Tests

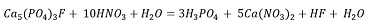

Solutions containing phosphate and calcium ions are required for the formation of calcium phosphates. Equation 1 represents the leaching reaction of fluorapatite with nitric acid, which produces phosphoric acid and calcium nitrate, while Equation 2 shows the leaching reaction of calcite, which also yields calcium nitrate.

Both reactions generate a solution containing calcium; however, mass balance shows that the largest calcium contribution comes from fluorapatite (Ec.1).

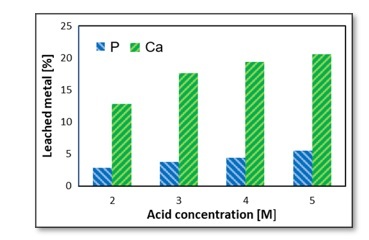

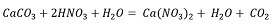

Figure 2 illustrates the percentages of P and Ca present in the leachate, revealing a directly proportional relationship between the concentrations of P and Ca ions and the nitric acid concentration.

Figure 2.

P and Ca

Extraction in the Leaching Process

Figure 2.

P and Ca

Extraction in the Leaching Process

Source: Author.

The extraction of P and Ca ions is limited by the concentration of HNO. in the solution. For example, a 75 g sample of PR contains approximately 10.08 g of phosphorus, equivalent to 0.325 moles. In an acid solution with a concentration of 3 M, there are 0.675 moles of HNO3 available.

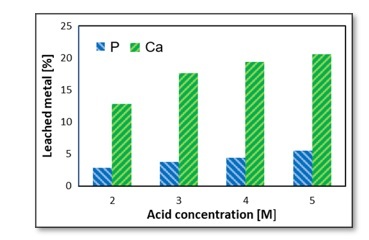

According to the stoichiometric relationship in Equation 1 (10 HNO3 / Ca5 (PO4)3F), this amount of HNO3 is insufficient to completely react with the calcium phosphate, indicating that HNO3 is the limiting reagent and, consequently, the extraction of P and Ca ions is restricted by its availability. When the pH of the leaching solutions is adjusted to different values (3, 5, and 10), the effect of NaOH addition is represented by the reaction in Equation 3:

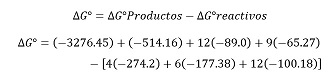

∆G°=-2533.31 Kcal/mol

The previous calculations indicate that with a negative ΔG, the reaction proceeds spontaneously, leading to the simultaneous precipitation of hydroxyapatite and brushite. In this case, NaOH acts as the limiting reagent, being fully consumed as new calcium phosphate phases, favored by the presence of P and Ca, are generated. Studies have demonstrated that various calcium phosphates can be obtained from solutions enriched with Ca2+ and PO43-[26].

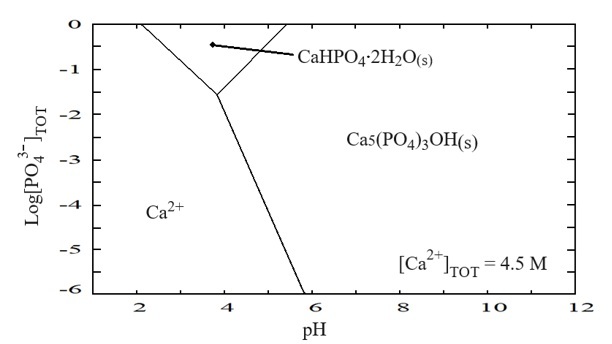

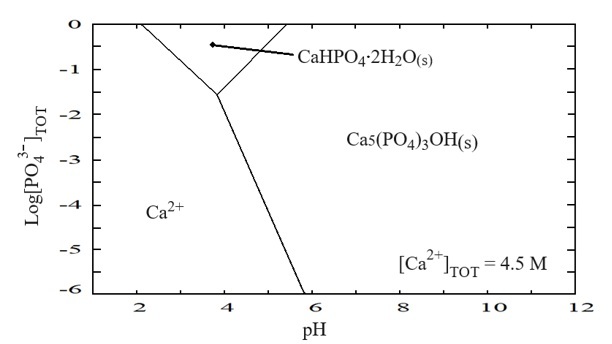

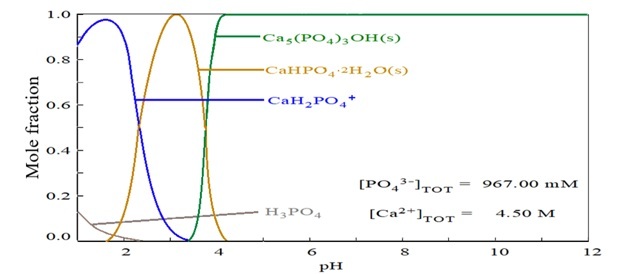

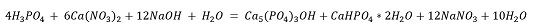

The pH plays a crucial role in determining which calcium phosphate phase predominates, as illustrated in the thermodynamic stability diagram P–Ca–H2O (Figure 3). Two distinct solid phases are shown: dihydrated calcium phosphate (brushite (CaHPO4) ·2H2O) and hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3OH). Brushite is stable at 0.3 M concentration of P, 4.5 M of Ca, 3M of HNO3, and pH values between 2 and 5, whereas hydroxyapatite is stable at concentrations up to 1 M of P, 4.5 M of Ca, 3 M of HNO3, and pH values over 6. The higher the pH, the greater the stability of the hydroxyapatite phase.

Figure 3.

Diagram of

species predominance for phosphorus - calcium - water system at 25 °C and 3 M

HNO3

Figure 3.

Diagram of

species predominance for phosphorus - calcium - water system at 25 °C and 3 M

HNO3

Source: Author.

The type of calcium phosphate obtained depends largely on factors such as the Ca/P ratio resulting from the phosphate rock leaching process, the reaction pH, and the rate at which the pH modifier is added. Although this study did not specifically analyze precipitation kinetics, the literature and the experimental conditions suggest that kinetics may have significantly influenced the phases formed. In general, the precipitation rate directly affects nucleation and crystal growth: rapid precipitation, particularly under certain concentration and agitation conditions, tends to favor the formation of amorphous or metastable phases, while slower precipitation allows greater structural reorganization, promoting the formation of more stable crystalline phases such as hydroxyapatite. Thus, precipitation kinetics can play a decisive role in the morphology, crystallinity, and phase of the products obtained [27][28].

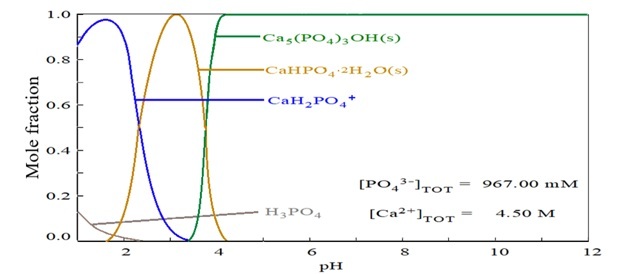

Figure 4 shows the distribution of calcium phosphate species as a function of pH. At the intersections of the curves, the molar fractions of the predominant species are equal. Phosphoric acid (H3PO4) is present in P- and Ca-containing solutions at pH values below 3, while aqueous calcium phosphate (CaH2PO4

+) predominates between pH 0 and 2. Solid phases emerge at higher pH: brushite (CaHPO4·2H2O), the most common in this range, occurs between pH 2 and 4, whereas hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3OH) becomes the dominant phase above pH 4. Hydroxyapatite is widely reported in the biomedical and bioceramics fields [29-34].

Figure 4.

Distribution diagram of calcium and phosphorus species as a function of pH

Figure 4.

Distribution diagram of calcium and phosphorus species as a function of pH

Source: Author.

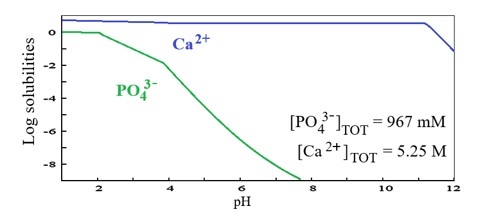

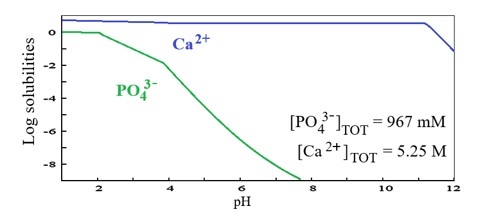

Figure 5 is a speciation diagram for the binary P – Ca system, where the high stability of the Ca 2+ ion is evident across the entire pH scale. In contrast, the phosphate ion becomes increasingly negative as the average pH rises, which explains the phase transitions shown in Figure 4. Notably, gradient changes occur between pH 2 and 4 with the formation of brushite (Figure 4), and again above pH 4 as brushite transforms into hydroxyapatite (Figure 4).

Figure 5.

Speciation

diagram for the binary (PO43–) – (Ca2+) system

Figure 5.

Speciation

diagram for the binary (PO43–) – (Ca2+) system

Source: Author.

Precipitation of Solid Varieties

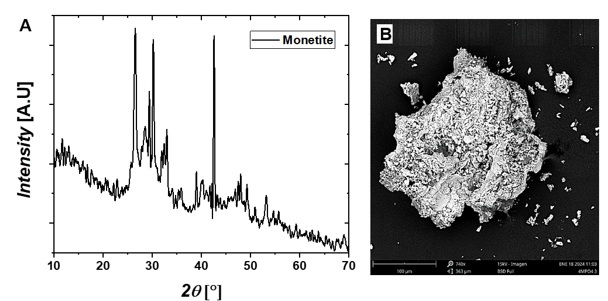

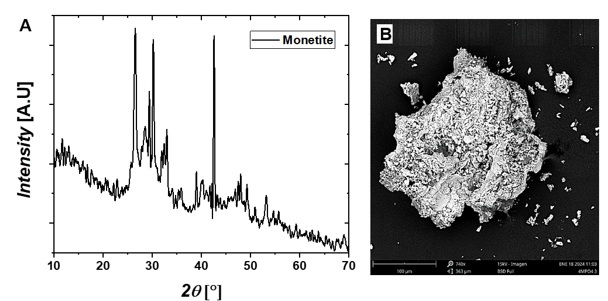

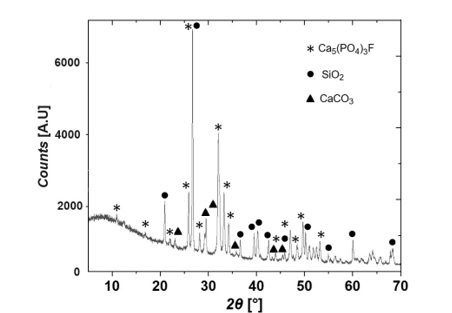

The solids obtained by precipitation at pH values of 3, 5, and 10 were characterized using XRD and SEM. Figure 6A shows the diffractogram of the solid precipitated at pH 3, where a single phase identified as monetite (CaHPO4) was observed. This phase corresponds to brushite once the water is eliminated from the composition by heating the precipitated sample at pH 3 to 100 °C. The crystalline monetite phase exhibits characteristic peaks at 26.36(0) °, 26.54(7) ° and 30.24(1) °, corresponding to diffraction planes (002), (200), (-120), with lattice parameters a = 6.9100 Å, b = 6.6270 Å and c = 6.9980 Å, α = 96.34 ◦, β = 103.82 ◦, and γ = 88.33 °.

Figure 6.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated monetite

at pH 3

Figure 6.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated monetite

at pH 3

Source: Author.

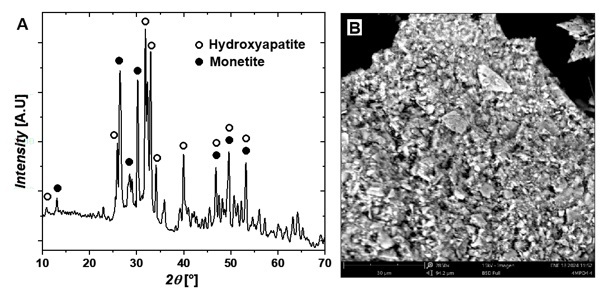

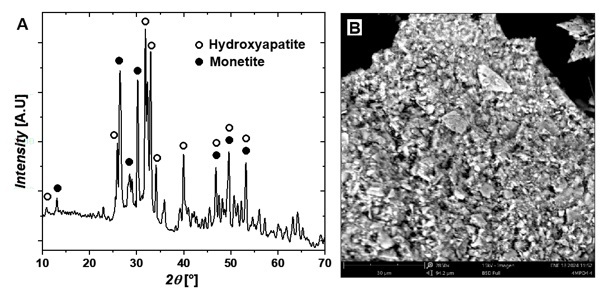

Figure 7A presents the diffractogram of solids precipitated at pH 5. According to the stability diagram in Figure 3, these solids correspond to two phases in similar proportions, identified as 56% hydroxyapatite and 44% monetite. The diffractogram displays the characteristic peaks of each phase, consistent with results reported by other researchers [35-37].

Figure 7.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated monetite

and hydroxyapatite at pH 5

Figure 7.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated monetite

and hydroxyapatite at pH 5

Source: Author.

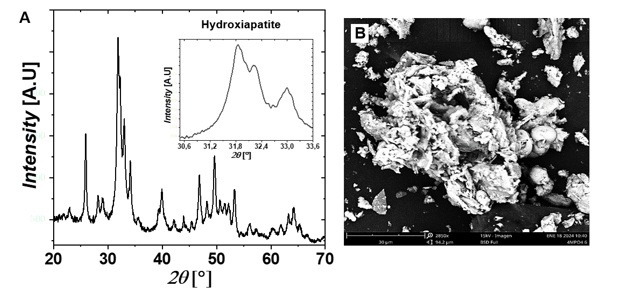

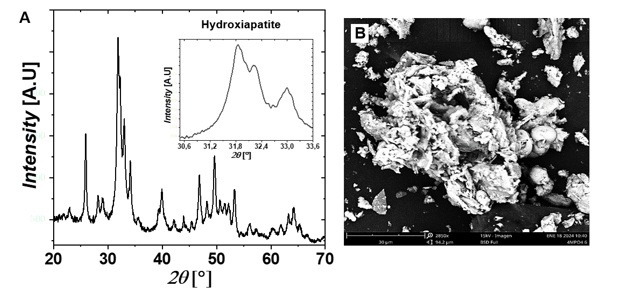

Figure 8A shows the diffraction pattern of a phase identified as hydroxyapatite. This monoclinic phase is characterized by lattice parameters a = 9.4214 Å, b = 18.8428 Å, and c = 6.8814 Å, with α = 90°, β = 90°, and γ = 120°. The characteristic triad of monoclinic hydroxyapatite is also clearly visible in the range 2θ = 30°–35°, corresponding to the Miller indices (221), (−222), and (−360).

Figure 8.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated hydroxyapatite at pH 10

Figure 8.

XRD

patterns plot and B. SEM images of the precipitated hydroxyapatite at pH 10

Source: Author.

Figures 6B,

7B, and 8B present microphotographs of the solids precipitated at pH 3, 5, and 10, respectively. The crystals obtained exhibit plate-like structures with flat surfaces, and their growth at different granulometries reflects the production parameters established during the precipitation process.

Conclusions

Leaching phosphate rock with nitric acid makes it possible to obtain solutions containing up to 5% P ions and 20% Ca ions, with the quantity of leached metals being directly proportional to the acid concentration in the range of 2–5 molars.

The pH plays a decisive role in the precipitation of calcium phosphates when sodium hydroxide is added to acid solutions containing phosphate and calcium ions. Brushite ((CaHPO4) ·2H2O is the dominant phase at pH 2–3, but it gradually transforms into hydroxyapatite (Ca5(PO4)3OH) as the pH rises above 4, a process driven by a ΔG° of −2533.31 kcal/mol. This behavior is illustrated in the species predominance diagram and the distribution diagram, which show the transition of calcium phosphate into brushite at pH 2–3 and its subsequent transformation into hydroxyapatite at pH 3–4.

These conclusions are supported by XRD analysis and SEM images of solids precipitated at pH 3, 5, and 10, which identified 100% monetite, a mixture of monetite and hydroxyapatite, and 100% hydroxyapatite, respectively.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, the

Universidad Santo Tomás, Tunja, and MinCiencias

project SGR - CTI call 006-2019, BPIN 2020000100507, internal code 74957.

References

[1] Heaney R.P. Phosphorus. In: Erdman JW, Macdonald IA, Zeisel SH, eds. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 10th ed. Washington, DC: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:447-58.

[2] Zapata, F.; Roy, R. N. 2007. Utilización de las Rocas Fosfóricas para una Agricultura Sostenible. Boletín FAO No. 13. OIEA-FAO. Roma, Italia. 94 p.

[3] Minerals Education Coalition, SME Foundation, https://mineralseducationcoalition.org/minerals-database/phosphate-rock

[4] Abioye O. Fayiga and O.C. Nwoke. 2016. Phosphate rock: origin, importance, environmental impacts, and future roles. Environmental Reviews. 24(4): 403-415. https://doi.org/10.1139/er-2016-0003

[5] Mineral Commodity Summaries 2024. Obtenido de https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/mcs2024

[6] Sánchez Guevara, C. (2024, March 11). LA PRODUCCIÓN DE ROCA FOSFÓRICA EN EL MUNDO. https://alimentosypoder.com/2024/03/11/la-produccion-de-roca-fosforica-en-el-mundo-2023/

[7] Agencia Nacional de Minería – ANM. Boletín estadístico informativo, minería en cifras. Enero de 2024. Sitio web: https://mineriaencolombia.anm.gov.co/sites/default/files/docupromocion/Bolet%C3%ADn%20Miner%C3%ADa%20en%20Cifras%20-%20enero%202024%20%283%29.pdf

[8] Jasinski S. M., Mineral Industry Surveys: Annual Phosphate Rock Review 2023, United States Geological Survey, 2024.

[9] The Global Economy / World Bank, “Phosphate rock price (USD per metric ton),” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://ycharts.com/indicators/morocco_phosphate_rock_price

[10] Avşar C. & Gezerman A.O., “An evaluation of phosphogypsum (PG)-derived nanohydroxyapatite (HAP) synthesis methods and waste management as a phosphorus source in the agricultural industry,” Medziagotyra, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 247–254, 2023. https://doi.org/10.5755/j02.ms.31695

[11] I. Bouchkira, A.M. Latifi, L. Khamar & S. Benjelloun, “Modeling and multi-objective optimization of the digestion tank of an industrial process for manufacturing phosphoric acid by wet process,” Computers and Chemical Engineering, vol. 156, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2021.107536

[12] Ryszko, U.; Rusek, P.; Kołodyńska, D. Quality of Phosphate Rocks from Various Deposits Used in Wet Phosphoric Acid and P-Fertilizer Production. Materials 2023, 16, 793. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16020793

[13] Zhang P., Comprehensive Recovery and Sustainable Development of Phosphate Resources, Procedia Engineering, Volume 83, 2014, Pages 37-51, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.09.010.

[14] Espinel Pérez N.M., “Synthesis of thermophosphate fertilizers by a plasma torch,” Organic Fertilizers - New Advances and Applications, Mar. 28, 2023. https://doi:10.5772/intechopen.1001352

[15] Benataya, K.; Lakrat, M.; Hammani, O.; Aaddouz, M.; Ait Yassine, Y.; Abuelizz, H.A.; Zarrouk, A.; Karrouchi, K.; Mejdoubi, E. Synthesis of High-Purity Hydroxyapatite and Phosphoric Acid Derived from Moroccan Natural Phosphate Rocks by Minimizing Cation Content Using Dissolution–Precipitation Technique. Molecules 2024, 29, 3854. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29163854

[16] Sainz Díaz, C. I., Villacampa, A., & Otálora, F. (2004). Crystallographic properties of the calcium phosphate mineral, brushite, by means of first principles calculations. American Mineralogist, 89, 307–313. https://doi.org/10.2138/am-2004-2-308

[17] Nath, S., Biswas, K., & Basu, B. (2008). Phase stability and microstructure development in hydroxyapatite-mullite system. Scripta Materialia, 58(12), 1054–1057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2008.01.045

[18] Aminzare, M., Eskandari, A., Baroonian, M. H., Berenov, A., Razavi Hesabi, Z., Taheri, M., & Sadrnezhaad, S. K. (2013). Hydroxyapatite nanocomposites: Synthesis, sintering and mechanical properties. In Ceramics International (Vol. 39, Issue 3, pp. 2197–2206). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.09.023

[19] Sánchez-Enríquez, J., & Reyes-Gasga, J. (2013). Obtaining Ca(H2PO4)2·H 2O, monocalcium phosphate monohydrate, via monetite from brushite by using sonication. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry, 20(3), 948–954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.10.019

[20] Bakher, Z., & Kaddami, M. (2018). Thermodynamic equilibrium in the system H2O+P2O5+CaCO3 at 25 and 70 °C: Application for synthesis of calcium phosphate products based on calcium carbonate decomposition. Fluid Phase Equilibria, 456, 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fluid.2017.10.005

[21] Döbelin, N., Maazouz, Y., Heuberger, R., Bohner, M., Armstrong, A. A., Wagoner Johnson, A. J., & Wanner, C. (2020). A thermodynamic approach to surface modification of calcium phosphate implants by phosphate evaporation and condensation. Journal of the European Ceramic Society, 40(15), 6095–6106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.07.028

[22] Elbashir, S., Broström, M., & Skoglund, N. (2024). Thermodynamic modelling assisted three-stage solid state synthesis of high purity β-Ca3(PO4)2. Materials and Design, 238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2024.112679

[23] Hasikovaa J. *, Sokolov A., Titov V., Dirba A. “SYMPHOS 2013”, 2nd International Symposium on Innovation and Technology in the Phosphate Industry. On-Line XRF Analysis of Phosphate Materials at Various Stages of Processing. Procedia Engineering 83 (2014) 455 – 461. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2014.09.078

[24] Jamil Safi M., M. Bhagwanth Rao, K. Surya Prakash Rao, and Pradip K. Govil. X-RAY SPECTROMETRY. X-Ray Spectrom. 2006; 35: 154–158. Published online 7 April 2006 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com).Chemical analysis of phosphate rock using different methods—advantages and disadvantages. https://doi.org/10.1002/xrs.886.

[25] Cevik U., Baltas H., Tabak A., Damla N., Radiological and chemical assessment of phosphate rocks in some countries, Journal of Hazardous Materials, Volume 182, Issues 1–3, 2010, Pages 531-535, ISSN 0304-3894, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.06.064.

[26] Aboudzadeh, N., Dehghanian, C., & Shokrgozar, M. A. (2019). Effect of electrodeposition parameters and substrate on morphology of Si-HA coating. Surface and Coatings Technology, 375, 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surfcoat.2019.07.016

[27] Sadat-Shojai M., Khorasani M.T., Dinpanah-Khoshdargi E., and Jamshidi A., “Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite with diverse structures,” 2013, Elsevier Ltd. doi: https://10.1016/j.actbio.2013.04.012

[28] A. Pedro, “Estudio para la obtención de hidroxiapatita a partir de roca fosfórica, para la remoción de flúor en aguas de pozo”, 2015. https://cideteq.repositorioinstitucional.mx/jspui/bitstream/1021/338/1/Estudio%20para%20la%20obtención%20de%20hidroxiapatita%20a%20partir%20de%20roca%20fosfórica%2c%20para%20la%20remoción%20de%20flúor%20en%20aguas%20de%20pozo_rees.pdf

[29] Pandayil JT, Boetti NG, Janner D. Advancements in Biomedical Applications of Calcium Phosphate Glass and Glass-Based Devices—A Review. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2024; 15(3):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/jfb15030079

[30] Canillas M., Pena P., Antonio H. de Aza, Rodríguez M. A. Calcium phosphates for biomedical applications. Vol. 56. Issue 3. Pages 91-112 (May - June 2017). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bsecv.2017.05.001

[31] Habraken W., Habibovic P., Epple M., Bohner M., Calcium phosphates in biomedical applications: materials for the future?, Materials Today, Volume 19, Issue 2, 2016, Pages 69-87, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mattod.2015.10.008

[32] Magnaudeix A. Calcium phosphate bioceramics: From cell behavior to chemical-physical properties. Front. Biomater. Sci., 29 August 2022. Sec. Bio-interactions and Bio-compatibility. Volume 1 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fbiom.2022.942104

[33] Nathan W. Kucko, Ralf-Peter Herber, Sander C.G. Leeuwenburgh, John A. Jansen. Chapter 34 - Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics and Cements, Editor(s): Anthony Atala, Robert Lanza, Antonios G. Mikos, Robert Nerem, Principles of Regenerative Medicine (Third Edition), Academic Press, 2019, Pages 591-611, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809880-6.00034-5

[34] Eliaz N, Metoki N. Calcium Phosphate Bioceramics: A Review of Their History, Structure, Properties, Coating Technologies and Biomedical Applications. Materials. 2017; 10(4):334. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10040334

[35] Jokić B., Mitrić M., Radmilović V., Sasa Drmanić, Petrović R., Janaćković D., Synthesis and characterization of monetite and hydroxyapatite whiskers obtained by a hydrothermal method, Ceramics International, Volume 37, Issue 1, 2011, Pages 167-173, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceramint.2010.08.032

[36] Rauf Khan S., Ali S., Zahra G., Jamil S., Saeed M., Synthesis of monetite micro particles from egg shell waste and study of its environmental applications: Fuel additive and catalyst, Chemical Physics Letters, Volume 755, 2020, 137804, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137804.

[37] Prado Da Silva M.H., Lima J.H.C., Soares G.A., Elias C.N., de Andrade M.C., Best S.M., Gibson I.R., Transformation of monetite to hydroxyapatite in bioactive coatings on titanium, Surface and Coatings Technology, Volume 137, Issues 2–3, 2001, Pages 270-276, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0257-8972(00)01125-7.

Notes

*

Research article

Author notes

a Corresponding author. E-mail: sandra.diazb@usantoto.edu.co

Additional information

How to cite this article: S C Diaz Bello, N R Rojas Reyes, G M Soto Calle, A A Gómez Zapata, “Thermodynamic Analysis in the Obtention of

Calcium Phosphates from Phosphate Rock” Ing. Univ. vol. 29, 2025. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.iued29.taoc

[ Ec. 1]

[ Ec. 1] [Ec. 2]

[Ec. 2]

[ Ec. 3]

[ Ec. 3]