The interpretation of the Church model in Eph 5:21-33 continues to raise significant questions among Pauline scholars. The use of the term σῶμα (body), to describe the Church in Pauline literature may suggest a conceptual continuity between the organic understanding of the Christian community found in 1Cor 12:12-27 and the ecclesiology in Eph 5:21-33. Accordingly, the assertion in Eph 5:30—“we are members (μέλη) of his body (σῶμα)”—can be viewed as an extension of the formulation in 1Cor 12:27: “You are the body (σῶμα) of Christ, and individually members (μέλη) of it” (NRSV).

Some scholars argue that the notion of σῶμα reflects the structure of the Christian assemblies in Asia Minor. Others, however, emphasize the discontinuity between the ecclesiological models of the Pauline and deutero-Pauline letters, specifically the shift from local communities’ structures to the ideal of a universal Church. More recently, some authors have proposed that the understanding of the Church as a body in the deutero-Pauline letters marks a transition to the household model. In this view, Ephesians and Colossians integrate the structure of the οἶκος-Church with that of the ἐκκλησία-Church to mediate internal conflicts stemming from diverse social identities.

1

A proper understanding of the model of the Church in Eph 5:21-33 begins with an accurate interpretation of the metaphor according to which the Church is a body (σῶμα), but must also account for the metaphor in this passage according to which Christ is the head (κεφαλή), a concept predominantly associated with the deuteroPauline epistles (Col 1:18; 2:10; Eph 1:22; 4:15; 5:23). This paper seeks to analyze the interplay between the metaphors of κεφαλή and σῶμα in Eph 5:21-33. It reviews the feminist and emancipatory interpretations of the head-body metaphor, proposed by Schüssler Fiorenza, Gil Arbiol, and Mollenkott.

2

These scholars rightly argue that a nuanced understanding of the head-body metaphor is essential for interpreting the ecclesial model in Ephesians, but also for understanding its implications for the marital relationship. At the same time, they emphasize the hierarchical relationship implied by the κεφαλή metaphor, raising concerns about how this passage has been received and applied within Christian communities.

In contrast to scholars who emphasize the singular σῶμα metaphor and its association with “the imperial-kyriarchal pattern of subjection and subordination,”

3

those focusing on the rhetorical structure of Eph 5:21-33 argue that the κεφαλή and σῶμα metaphors should be understood as a dual metaphor, in which the image of the body is intrinsically linked to that of the head.

4

In Ephesians, these metaphors are further connected to the theological concepts of πλήρωμα

5

and μυστήριον.

6

This paper uses three methodological approaches: classical rhetoric, modern rhetoric, and Cognitive Linguistics. The first framework elucidates the metaphorical or figurative meaning of the metaphors, the second examines their heuristic capacity, and the third investigates their illocutionary force. Together, these approaches reveal an ecclesial model that embodies a distinct Christological and eschatological reality, characterized by the unity of its members and their comprehension of the μυστήριον. The mystery of Christ (Eph 3:4; 5:32) refers to the risen Christ, who not only facilitates the growth and edification of the entire body (Eph 4:15-16), but also confers upon the Church a new status: that of a resurrected body.

7

Indeed, the mystery of the Church (Eph 5:32) reveals the true nature of the universal Church.

The Function of ὑποτάσσω in Eph 5:21

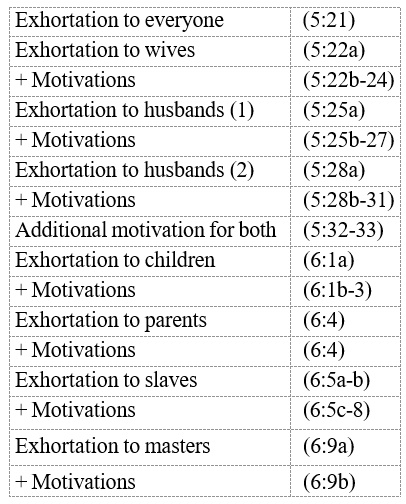

Ephesians 5:21–6:9 follows the characteristic structure of Pauline exhortations: imperative, rationale, and further imperative. Although the initial exhortation in Eph 5:21 applies universally, calling all believers to “be subject to one another” (ἀλλήλοις), which includes husbands and wives, children and parents, and slaves and masters,

8

the rationale for this mutual submission varies for each respective group.

The exhortation to wives (Eph 5:22-24) is underpinned by Christological and ecclesiological motivations while the exhortation to husbands (Eph 5:25-31) draws upon both Christological and anthropological grounds. The exhortation to husbands includes two imperatives to love their wives (vv. 25 and 28). The second imperative (v. 28) reiterates the command to love from v. 25 but introduces an additional rationale: “as their own bodies,” a motivation not previously articulated in vv. 25b-27. Additionally, this section incorporates a biblical argument based on Gen 2:24, which is absent in the earlier exhortation and the instructions to slaves and masters.

The motivations presented in vv. 32-33 incorporate both Christological and ecclesiological themes, particularly through the notion of μυστήριον, serving as a summary of the exhortations directed at both husbands and wives. The exhortation to children (Eph 6:1-3) includes a biblical rationale (cfr. Ex 20:12; Deut 5:16) and includes a promise of blessing. Instruction to parents (Eph 6:4), however, is limited to a kuriological basis. The exhortation to slaves (Eph 6:5-8) alternates between Christological, anthropological, and kuriological motivations, whereas the instruction to masters (6:9) draws upon both anthropological and kuriological reasoning.

Pauline scholars have long debated the interpretation of the opening exhortation in Eph 5:21. It remains unclear whether, in this context, the exhortation denotes unilateral submission or reciprocal subordination, whether it exclusively refers to the submission of wives to the head (κεφαλή) or also applies to husbands.

Armstrong proposes a linguistic approach to clarify the concept of submission.

9

His analysis elucidates both the syntax of the passage and the verbal aspects of ὑποτάσσω. His syntactical study indicates that Eph 5:21 can be understood as a transitional statement. First, the participle ὑποτασσόμενοι—functioning adverbially—is linked to the previous participles in vv. 19-20 (λαλοῦντες [...] ᾄδοντες καὶ ψάλλοντες [...] εὐχαριστοῦντες) and is subordinate to the imperative πληροῦσθε in v. 18b. Second, the participle ὑποτασσόμενοι also introduces the relationships between wife and husband and between the Church and Christ, as articulated in the following verses (22-24). Moreover, Armstrong’s study of the verbal aspect of ὑποτασσόμενοι in Eph 5:21 reveals that the middle voice of the participle highlights, first, the “direct participation” and “specific involvement” of the subjects,

10

and second, the imperfective aspect of the present action, indicating that it is ongoing.

11

Armstrong makes two further remarks in his syntactic and verbal analysis of Eph 5:21-33. First, he notes that the “reciprocal” middle voice of ὑποτασσόμενοι is paired with the reciprocal pronoun ἀλλήλοις. Second, he points out that the use of the subjunctive φοβῆται (instead of ὑποτάσσω) in Eph 5:33 affirms the mutual need between husbands and wives. Armstrong correctly concludes that “the verbal aspect, voice, mood, and agency of ὑποτάσσω in Eph 5:21 suggest a voluntary, mutual interchange and direct participation of both husbands and wives in relation to the verb.”

12

Aletti also emphasizes the reciprocal interpretation of ὑποτάσσω in Eph 5:21.

Aletti also emphasizes the reciprocal interpretation of ὑποτάσσω in Eph 5:21. He notes that although the verb ὑποτάσσω is typically associated with subordination, often understood as inferiority in rank or obedience, the author of the letter clearly distinguishes ὑποτάσσω from ὑπακούω in this context. Aletti clarifies that the submission required of the wife does not imply an attitude of obedience, as is required of children or young people. Instead, her acknowledgment of the husband’s juridical—superior—status does not entail a servile or childish demeanor. Thus, the submission required of one another—rather than obedience—means regarding others as superior to oneself.

13

The rhetorical and linguistic analysis of ὑποτάσσω in Eph 5:21 emphasizes its reciprocal meaning, suggesting that the submission in this verse applies to wives and husbands but also to children and parents as well as to slaves and masters. However, scholars approaching the text from a feminist perspective cast doubt on the reciprocal relationship described in the passage and the derived non-reciprocal ecclesial model. Instead, they argue that the household code in Ephesians presents “theologized” models aimed at reinforcing the submission of wives.

14

This critique calls for a careful study of both the imperatives and their corresponding rationales in the passage.

Feminist and Emancipatory Interpretations

Both feminist and emancipatory approaches to Eph 5:21-33 challenge its reception within the Christian tradition, though they do so in distinct ways. The feminist approach critiques the use of kuriological arguments to uphold a model of male authority and subordination in the Church. In contrast, the emancipatory reading questions the application of Eph 5:21-33 as a justification for abuse and violence by husbands in Christian communities and churches of various denominations. Despite their differing interpretations, both approaches acknowledge the significance of the head-body metaphor for understanding relationships within the Church.

Schüssler Fiorenza interprets the “head” and “body” metaphor in Eph 5:21-33 as reciprocal. She argues that while the relationship between Christ and the Church functions as a paradigm for marriage,

15

the marital relationship also becomes a paradigm for understanding the relationship between Christ and the Church.

16

Schüssler Fiorenza primarily focuses on the σῶμα metaphor, which she sees as subordinated to the κεφαλή). She emphasizes “the imperial-kyriarchal pattern of subjection and subordination, […] since the ekklesia-bride is totally dependent on or subject to her head or bridegroom.”

17

The interpretation that emphasizes the Church as the wife, subject to the head, understands the metaphor as reciprocal but applies it as if it were bidirectional, i.e., valid for the marital relationship in the same way it is for the relationship between Christ and the Church. This reading further treats the metaphor as though it had anthropological significance and were justified by considerations of power. Do the motivations in Eph 5:22-24 support this interpretation? Do the rationales provided for women suggest that the marital relationship may serve as a paradigm for the relationship between Christ and the Church?

Schüssler Fiorenza’s interpretation of the Church as bride suggests an imperialkyriarchal structure within the Church. However, this structure may not accurately capture the model of the Church conveyed by the metaphor when interpreted as a double metaphor. Furthermore, this interpretation may be misleading—if not contradictory—as it overemphasizes the metaphor’s explanatory function, despite the Schüssler Fiorenza’s acknowledgment that in Eph 5:21-33 the metaphor’s primary function is prescriptive rather than merely descriptive.

18

In line with Schüssler Fiorenza, Gil Arbiol interprets the σῶμα metaphor— understood as subordinate to the κεφαλή—by highlighting its hierarchical implications. The author situates the use of σῶμα metaphor in the deutero-Pauline letters as an extension of its earlier application in the Pauline epistles. In Ephesians and Colossians, the metaphor of the body undergoes a process of masculinization, significantly impacting the interpretation of Christology, ecclesiology, and the ethical values promoted in these letters.

19

Gil Arbiol argues that the metaphorical connection between Christ and the husband in Eph 5:21-33, mirrored by the connection between the Church and the wife, is constructed through the concept of “head,” a term attributed to both the husband and Christ, denoting their shared authority. As a result, the husband assumes the same authority over his wife that Christ holds over the Church.

20

Like Schüssler Fiorenza, Gil Arbiol interprets the submission of wives to their husbands within the framework of a patriarchal model.

21

According to Gil Arbiol, this model reflects the assimilation of Greco-Roman domestic roles into Christian communities. Both Ephesians and Colossians appear to have introduced this model to mitigate the conflicts provoked by the Pauline model in Christian communities—specifically, the challenges arising from a model that granted autonomy and prominence to subordinate individuals. Furthermore, the deutero-Pauline letters offer a theological justification for this model, elucidating how the second generation of Christians adapted to their evolving social circumstances in Asia Minor.

22

Gil Arbiol observes that Ephesians modifies this patriarchal model by introducing “the ‘self-sacrificial love’ (παραδίδωμι, Eph 5:25) of Christ for the Church as a model for the self-giving of husbands to their wives.”

23

Although Gil Arbiol does not explicitly state this, such a correction underscores the prescriptive, rather than descriptive, function of the metaphor. This observation, in turn, invites a reconsideration of the metaphor’s anthropological dimensions.

Mollenkott assesses various scholarly interpretations of the marital relationship in Ephesians, identifying both misinterpretations of its metaphors and overly expansive conclusions derived from feminist readings. In particular, the author scrutinizes interpretations by Thistlethwaite,

24

Schüssler Fiorenza, and Johnson. Rather than dismissing feminist perspectives wholesale, Mollenkott highlights emancipatory aspects within Eph 5:21-33 that offer “liberating alternative interpretations of Scripture” for abused women, while avoiding a direct challenge to the authority of the text.

25

Mollenkott argues that the analogy of the husband to Christ is inherently circumscribed by the text, as “the husband is compared to Christ only in Christ’s self-giving, self-humbling capacity.”

26

Mollenkott’s interpretation is largely accurate, as it (1) underscores the unilateral nature of the κεφαλή metaphor, applying it to the husband only insofar as he embodies Christ’s self-giving attitude, and (2) highlights its prescriptive, rather than descriptive, function. Although Mollenkott perceives the illocutionary force of the metaphor between the lines, arguing that a proper understanding brings to light the prophetic and liberating dimensions of Scripture, this interpretation does not fully address the complementary σῶμα metaphor (Church as the body of Christ) and overlooks the heuristic potential of the dual metaphor, which offers a creative model of the Church as μυστήριον.

The interpretations of the three mentioned authors focus on the translated meanings of the κεφαλή and σῶμα metaphors, seeking to clarify the comparisons they evoke, much like the approach of classical rhetoricians. However, their analyses neither fully explore the heuristic (or creative) potential of the metaphors, as modern rhetorical theory recommends, nor do they adequately account for the illocutionary force conveyed by the metaphors, as insights from Cognitive Linguistics indicate.

Imperatives and Rationales in Eph 5:22-24.25-30

Ephesians 5:22-24

The exhortation to wives in Eph 5:22 lacks a main verb; the reader must supply it from the participle of ὑποτάσσω in v. 21. This exhortation is further justified by the abbreviated expression “as to the Lord” (ὡς τῷ κυρίῳ). Additionally, the rationale proposed in Eph 5:23 for the subjection of wives to their husbands is notably ambiguous:

23For the husband is head of his wife

(ὅτι ἀνήρ ἐστιν κεφαλὴ τῆς γυναικὸς) [Socio-anthropological rationale]

just as Christ is the head of the Church

(ὡς καὶ ὁ Χριστὸς κεφαλὴ τῆς ἐκκλησίας), [Christological comparison]

he himself the savior of the body

(αὐτὸς σωτὴρ τοῦ σώματος). [Christological/soteriological rationale]

The statement regarding the husband as the head (κεφαλή) of the wife reflects a socio-anthropological perspective rather than a physical description. In the GrecoRoman familial structure, the pater familias is regarded as the head or chief of the household. However, the second statement, which includes a Christological comparison, does not confirm this socio-anthropological view but introduces a different meaning for “head” (κεφαλή), specifically as “head of the Church.” The interpretation of the comparison (ὡς) in Eph 5:23 is crucial for understanding the metaphor. One might assume that the Christological comparison carries a socio-anthropological meaning in which Christ would be the “head of the Church” as its chief. However, the third statement refutes this interpretation: Christ is the “head of the Church” insofar as he is its savior, the savior of the body. This third part of the rationale excludes both the physical and socio-anthropological meanings of the κεφαλή metaphor. Therefore, one cannot assume that the submission of wives to the “head” (κεφαλή) in Eph 5:23a is based on the physical or socio-cultural status of the husband. The husband is neither the wife’s physical head nor is he her savior, and even though he may be the chief of the Greco-Roman household, Ephesians does not ground the prescriptive function of the metaphor in this socio-anthropological status.

Although the metaphor of the head could apply to the husband insofar as he is like Christ,

27

loving his wife as Christ loves the Church, this direction of the metaphor only becomes evident in the rationale directed toward husbands in Eph 5:25-30.

28

What, then, is the meaning and significance of the κεφαλή metaphor? The sense of the expression seems to apply in only one direction: the relationship of Christ (head/κεφαλή) to the Church (body/σῶμα) serves as the paradigm or model for the marital relationship, but not the reverse. Moreover, the illocutionary force of the metaphor neither depends on a socio-anthropological description of the head/chief of the head/chief of thehousehold nor promotes a kyriological pattern of subjection, but rather a Christological model of self-emptying love. The Christological scope of the metaphor and its unilateral direction becomes clear in Eph 5:24:

24Just as the church is subject to Christ

(ἀλλ᾽ ὡς ἡ ἐκκλησία ὑποτάσσεται τῷ Χριστῷ), [Christological comparison]

so also, wives (οὕτως καὶ αἱ γυναῖκες) ought to be, [Exhortation]

to their husbands, in everything (τοῖς ἀνδράσιν ἐν παντί).

Ephesians 5:24, in fact, introduces a correctio or restriction to the argument: submission applies only to the extent that the Church body (ἐκκλησία σῶμα) submits to Christ, that is, out of respect and love for its Savior. However, one must acknowledge that the phrase “being subject in everything” (ἐν παντί) introduces further ambiguity into the reasoning, without clarifying the meaning of being subject to the Lord (ὡς τῷ κυρίῳ). The subsequent Christological argument in Eph 5:25-30 will need to clarify both the comparison with Christ (ὡς […] τῷ Χριστῷ) and the type of submission (ὑποτάσσω) promoted by the dual metaphor.

Ephesians 5:25-30

The exhortation to husbands in Eph 5:25-30 includes two instructions: “love (ἀγαπᾶτε) your wives” in v. 25 and “husbands should love (ὀφείλουσιν [καὶ] οἱ ἄνδρες ἀγαπᾶν) their wives” in v. 28. Each one of these exhortations to love are followed by a different set of rationales.

25Husbands, love your wives

(Οἱ ἄνδρες, ἀγαπᾶτε τὰς γυναῖκας), [Exhortation + Christological motivation]

just as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her,

(καθὼς καὶ ὁ Χριστὸς ἠγάπησεν τὴν ἐκκλησίαν καὶ ἑαυτὸν παρέδωκεν ὑπὲρ αὐτῆς),

26to make her holy by cleansing her with the washing of water by the word,

(ἵνα αὐτὴν ἁγιάσῃ καθαρίσας τῷ λουτρῷ τοῦ ὕδατος ἐν ῥήματι),

27to present the church to himself in splendor, without a spot or wrinkle or anything

of the kind, so that she may be holy and without blemish

(ἵνα παραστήσῃ αὐτὸς ἑαυτῷ ἔνδοξον τὴν ἐκκλησίαν, μὴ ἔχουσαν σπίλον ἢ ῥυτίδα ἤ τι

τῶν τοιούτων, ἀλλ᾽ ἵνα ᾖ ἁγία καὶ ἄμωμος). [Rationales x 3 purpose (ἵνα) clauses]

The exhortation to love one’s wife in Eph 5:25a reflects the language of ἀγάπη found in the preceding chapters (3:17, 19; 4:2, 15, 16; 5:2), where ἀγάπη/ἀγαπάω signify both Christ’s love and the bond of unity within the community. The Christological motivation in Eph 5:25b, introduced by the comparative phrase καθὼς καί, comprises two parallel clauses: “Christ loved the Church” and “gave himself up for her.” This act of self-sacrifice elucidates the nature of Christ’s love for the Church.

29

The rationale in Eph 5:26-27 is articulated through three purpose (ἵνα) clauses. The theme of holiness creates an inclusio between the first and third clauses, likely evoking Israel’s call to sanctification (Lev 11:44; 19:2).

30

The interpretation of the passive participle καθαρίσας in Eph 5:26 has been the subject of scholarly debate. The imagery of the purifying bath may invoke three potential references: (1) Baptism. (2) The Jewish liturgical preparation and presentation for marriage. (3) Moral purification. This image is further specified in the text by the dative ἐν ῥήματι, which could plausibly refer either to the proclamation of the gospel or to a confession of faith. Within the broader context, the image seems to evoke God’s unilateral initiative, akin to the depiction in Ezek 16:8–14, now applied to Christ.

31

While Christ’s presentation of the glorious Church in Eph 5:27ab may be understood through the lens of the spousal metaphor,

32

emphasizing the bride’s beauty or moral dignity, the third purpose clause in v. 27c underscores the Church’s moral vocation and call to sanctification.

Both the Christological motivation (sacrificial motive) in Eph 5:25 and the sequence of purpose clauses in Eph 5:25-27 highlight Christ’s initiative and the Old Testament motif of holiness. The Christological motivation further suggests that the marriage allegory functions in only one direction: Christ is presented as the example of love for husbands toward their wives, but not vice versa. Moreover, although the rationale may be interpreted through spousal imagery, neither the justification for loving wives nor the further purpose of this love explicitly identifies them with the

Church. This rationale does not, strictly speaking, involve either the σῶμα metaphor or the κεφαλή metaphor.

28In the same way, husbands should love their wives

(οὕτως ὀφείλουσιν [καὶ] οἱ ἄνδρες ἀγαπᾶν τὰς ἑαυτῶν [Exhortation]

γυναῖκας)

as they do their own bodies. (ὡς τὰ ἑαυτῶν σώματα). [Anthropological comparison]

He who loves his wife loves himself.

(ὁ ἀγαπῶν τὴν ἑαυτοῦ γυναῖκα ἑαυτὸν ἀγαπᾷ). [Anthropological rationales x 3]

29For no one ever hates his own body, but he nourishes

and cares for it,

(Οὐδεὶς γάρ ποτε τὴν ἑαυτοῦ σάρκα ἐμίσησεν ἀλλ᾽ ἐκτρέφει [dissuasion/ persuasion]

καὶ θάλπει αὐτήν),

just as Christ does for the Church, [Christological

(καθὼς καὶ ὁ Χριστὸς τὴν ἐκκλησίαν), rationale/comparison]

30for we are members of his body [Ecclesiological rationale]

(ὅτι μέλη ἐσμὲν τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ). [σῶμα metaphor]

The exhortation to love one’s wife in Eph 5:28 is substantiated by several anthropological arguments, both affirmative and preventative. These arguments justify love for one’s wife, first, by appealing to self-love (“he who loves his own wife loves himself”), and second, by discouraging self-hatred (“no one hates his own body [σάρξ]”). The second argument, therefore, further elucidates the anthropological analogy, explaining why love for one’s wife is compared to love for one’s own body—without conflating the wife with the body.

The concept of the body (σῶμα) plays a central role in this reasoning (vv. 28b-29a),

33

though here it does not function as a metaphor, as it does in Eph 1:22-23; 2:16; 4:12; 5:30. While the comparison introduced by “as” (ὡς) in v. 28b emphasizes the literal, anatomical sense of the body (σῶμα; see also σάρξ in v. 29a), the subsequent comparison in v. 29b,

34

“just as Christ” (καθὼς καί), is further substantiated in v. 30 by the metaphorical meaning of the body (σῶμα). This ecclesiological argument introduces a figurative sense of the body (σῶμα), suggesting that human care for the body (σάρξ) serves as an analogy for the relationship between Christ and the Church, the body of Christ (τοῦ σώματος αὐτοῦ).

35

The Christological rationale in Eph 5:29b-30 consists of both a Christological comparison (v. 29b) and an ecclesiological explanation (v. 30). While the Christological comparison in v. 29b echoes the imagery of the husband’s body (σῶμα) and flesh (σάρξ) from vv. 28b-29a, the ecclesiological explanation in v. 30 introduces the metaphor of the σῶμα. Indeed, the analogy in v. 29b cannot be separated from its explanatory formulation in v. 30. This ecclesiological justification in v. 30 recalls the concept of the ecclesial σῶμα—developed throughout the letter—while also foreshadowing the biblical argument in v. 31 (Gen 2:24).

36

The anthropological and Christological motivations in 5:28c-30 are, in fact, rooted in the broader context of the biblical creation narrative.

The exhortation, comparisons, and rationales in Eph 5:28-30 employ the notion of “body” with distinct yet complementary meanings: literal (σάρξ) and metaphorical (ἐκκλησία).

37

This imagery clarifies the nature of the love to which husbands are called. In Eph 5:25, this love may be described as “sacrificial,” whereas in Eph 5:29, it can be characterized as “somatic.” Both forms of love are grounded in Christology: sacrificial love reflects Christ’s self-giving for the Church, while somatic love illustrates Christ’s love for the Church. The combined use of these concepts is fully elucidated when considering the subsequent biblical rationale in v. 31 (Gen 2:24). Indeed, the justification for somatic love in Eph 5:31-33 extends beyond self-care for the body (σάρξ) and is substantiated by God’s initiative to create a bond of unity (εἰς σάρκα μίαν) between husband and wife.

The Mystery about Christ and the Church

The unity bond is illustrated in Eph 5:31 through the citation of Gen 2:24 and the introduction of the notion of μυστήριον. Aletti rightly observes that Gen 2:24 only partially reflects the relationship between Christ and the Church, as the expression “the two will become one flesh” does not entirely apply to them.

38

Eph 5:21-33 demonstrates that when a husband loves his wife as his own body, he effectively makes her his body—they become one flesh (σάρξ)—just as Christ made the Church his body, thereby creating a bond of unity. Thus, the husband’s love, rooted in Christ’s love, establishes a relationship that is divinely ordained from the beginning, but now reinterpreted in light of the Christ/Church relationship. This new understanding also clarifies the introduction of the term μυστήριον.

39

The notion of μυστήριον in Eph 5:32 could be interpreted in various ways: sacramental, typological, and analogical. The sacramental reading interprets Gen 2:24 as the justification for Christian marriage. The typological reading views marriage as a preparation—a τύπος—for the spousal relationship between Christ and the Church. The analogical reading emphasizes the union between Christ and the Church. While the quotation from Gen 2:24 may prefigure Christian marriage in a certain sense,

40

in the immediate context of Eph 5:31-32, it primarily highlights the close bond between Christ and the Church.

41

The expression τὸ μυστήριον τοῦτο μέγα ἐστίν in Eph 5:32 has historically been interpreted through at least three hermeneutical frameworks.

42

(1) In the spousal interpretation, the demonstrative pronoun τοῦτο carries an anaphoric function. Thus, the mystery (μυστήριον) refers to the relationship between husband and wife outlined in the preceding verse (Eph 5:31). (2) In the ecclesial interpretation, the pronoun τοῦτο points forward to the Church (ἐκκλησία) as mentioned in 5:32b.

43

(3) In the analogical interpretation, the mystery (μυστήριον) encompasses both unions—the marriage of man and woman, and the union between Christ and the Church. This third interpretation seems to more accurately reflect both the argumentative progression of the passage and the author’s reinterpretation of Genesis.

The μυστήριον referring to Christ and the Church (εἰς Χριστὸν καὶ εἰς τὴν ἐκκλησίαν) suggests an unparalleled novelty in understanding the coherence of God’s saving plan.

44

Its formulation in Eph 5:32 links both to the exhortations directed at the bridegroom and to the reinterpretation of Gen 2:24. Thus, this μυστήριον—the bond of unity between Christ and the Church—encapsulates in this passage the nature of God’s new act of salvation/creation, already suggested in Genesis and now manifested in the Church, understood as the body of Christ.

The double metaphor and the model of the Church

Some scholars trace the Old Testament roots of the notion of μυστήριον to the book of Daniel (2:19, 28-30, 47),

45

where God’s plan of salvation is referred to as “mysteries” (μυστήρια). Daniel 2:28-29 also describes humanity’s inability to know these mysteries. Although God reveals His purpose, the understanding of these revelations remains beyond human comprehension. Only God can disclose to humans “what will happen at the end of days” (Dan 2:28). Ephesians and Colossians identify the future comprehension—the full understanding—of these “mysteries” (μυστήρια) on the final day with the event of Jesus Christ. Ephesians, in particular, uses the biblical concept of μυστήριον to substantiate (1) a new understanding of God’s plan of salvation, specifically the proclamation of Jesus Christ crucified, dead, and resurrected; (2) the association of this message with the Church itself, mainly the bond of unity between Christ (κεφαλή) and the Church (σῶμα); and (3) the knowledge conveyed by the dual metaphor of κεφαλή (head) and σῶμα (body).

46

The rhetorical analysis of the arrangement of the exhortations and their rationales in Eph 5:21-33 underscores the importance of interpreting the κεφαλή and σῶμα metaphors as dual or correlated metaphors. The images of head and body are employed not to formulate the exhortations themselves, but to provide their underlying rationales. This analysis reveals that the figurative meaning of κεφαλή (head) applies unidirectionally (cf. vv. 22-24), while the figurative meaning of σῶμα (body) alternates with its anatomical sense (σῶμα/σάρξ) (cf. vv. 28-30). Furthermore, a classical rhetorical study of the κεφαλή and σῶμα imagery,

47

when considered alongside the rhetorical analysis of this passage, demonstrates that these metaphors (1) convey a dual analogy (between Christ and the head, and between the Church and the body); (2) encapsulate the notion of unity (since a body cannot exist without a head); and (3) introduce a paradoxical relationship, wherein the union of head and body is understood as μυστήριον, as is Jesus Christ. Nevertheless, recent scholarship on Pauline metaphors has emphasized that modern rhetorical theories and Cognitive Linguistics offer a more comprehensive understanding than what ancient rhetoric alone can provide.

Regarding metaphor, several key observations can be made: (1) A metaphor cannot be reduced to a simple comparison; it goes beyond substitution or embellishment.

48

(2) The heuristic function of metaphor reveals new relationships, much like a model uncovers new relationships in scientific discourse.

49

(3) Cognitive Metaphor Theory “regards metaphors not just as a rhetorical device to adorn speech; rather, they are a fundamental way of conceptualizing the world around us.”

50

Recent studies on performative utterances also differentiate between the sociopolitical and phenomenological functions of language.

51

Both demonstrate language’s capacity to construct reality.

52

The former relies on the sociopolitical context, shaping communal or new social orders, while the latter reflects the speaker’s intentionality, generating a world of phenomena.

The double metaphor κεφαλή-σῶμα possesses heuristic capacity and illocutionary force. It generates both an ethical model for marriage and an ecclesial model that extends beyond local assemblies, promoting unity rather than subordination. In Ephesians, the heuristic and illocutionary aspects of the metaphor unfold in unexpected ways, as they intertwine with the Church’s designation as μυστήριον. The mystery τοῦ Χριστοῦ (Eph 3:4; 5:32) refers to the risen Christ, who fosters the growth and edification of the body (Eph 4:15-16) and who confers on the Church the status of a resurrected body, while the mystery τῆς ἐκκλησίας (Eph 5:32) reflects the identity of the universal Church. The concept of μυστήριον also underscores both the continuity and discontinuity between the Old Testament’s salvific design and its New Testament realization.

Understanding the double metaphor of κεφαλή-σῶμα illuminates the ecclesiological model presented in Ephesians. It clarifies the universal identity of the Church and illuminates additional elements that define its nature. Some of these elements are prescriptive rather than descriptive, while others are creative rather than continuative. For instance, this model does not mandate submission but rather cultivates love and respect, conceived as a bond of unity. It neither conforms to nor accommodates the Greco-Roman patriarchal model but instead establishes a reciprocal relationship within the ecclesial context (between Christ and the Church), which in turn gives rise to a nuanced social identity (between wife and husband as one [ὑμεῖς οἱ καθ᾽ ἕνα, Eph 5:33], just as between the Church and Christ).

53

Although the model of the Church in Eph 5:21-33 is certainly shaped by the double metaphor of κεφαλή-σῶμα and the notion of μυστήριον, it would be imprecise to establish the Church’s model in Ephesians solely based on this double metaphor. Some scholars note that, in addition to the κεφαλή-σῶμα metaphor, Ephesians employs other metaphors toescribe the Church.

54

Most of these are anthropological and architectural metaphors that reflect an organic model, conveying the ideas of growth (toward maturity, to the measure of Christ) and cohesion (in the Spirit). Nonetheless, by employing the notion of μυστήριον, Eph 5:21-33 emphasizes a Christological and ethical model of the Church, with the latter being the consequence of the former. This model complements and amplifies the designation of the Church as the “fullness of Christ” (Eph 1:23), i.e., the Church understood as “his body” (τὸ σῶμα αὐτοῦ), “the fullness of the one who fills everything in every way” (τὸ πλήρωμα τοῦ τὰ πάντα ἐν πᾶσιν πληρουμένου).

Conclusion

The ecclesial model presented in Eph 5:21-33 is primarily shaped by the dual metaphor of κεφαλή-σῶμα. Through a synthesis of rhetorical analysis, insights from both classical and contemporary rhetoric, and Cognitive Linguistics, one can more fully grasp how this metaphor articulates the relationship between Christ and the Church, as well as its theological and ethical implications. Analyzing the structure of exhortations and rationales in Eph 5:21-33 reveals the function and boundaries of the metaphor. Elucidating its illocutionary force sheds light on its normative significance for Christian marriage, while clarifying its creative capacity illuminates the ecclesial model advanced in the letter. This study also demonstrates how, in Eph 5:21-33, the double metaphor of κεφαλή-σῶμα is intricately linked to the concept of μυστήριον, thereby generating a Christological and ethical paradigm for the universal Church.

The emerging model conveys both the universal identity of the Church and the call to sanctification in Christian marriage. While feminist interpretations of Eph 5:21-33 perceive the passage as reinforcing a patriarchal framework of submission, rhetorical analysis suggests that it points to a reciprocal, Christological model of the Church. Similarly, while emancipatory approaches interpret the passage as either supporting or challenging subversive models within Christian communities, rhetorical analysis emphasizes the ethical paradigm grounded in an organic vision of the body of Christ. The interpretation advanced in this study demonstrates that Eph 5:21-33 does not merely sanction male authority but rather reconfigures social roles through the transformative love of Christ.

In accordance with Paul’s use of the σῶμα metaphor, the deutero-Pauline letters expand the dual metaphor of κεφαλή-σῶμα, integrating additional layers of meaning, including the μυστήριον, which Christologically affirms both the bond of unity between Christ and the Church and its eschatological identity. This observation highlights Paul’s distinctive preference—continued by his school—for employing metaphors to convey the theological innovation introduced by his understanding of the Christ-event. Consequently, it underscores the importance of examining the heuristic potential and illocutionary force of Pauline metaphors, drawing not only on classical rhetorical frameworks but also on insights from modern rhetoric and Cognitive Linguistics.

References

Ådna, Jostein. “Die eheliche Liebesbeziehung als Analogie zu Christi Beziehung zur Kirche: Eine traditionsgeschichtliche Studie zu Epheser 5,21-33.” Zeitschrift für Theologie und Kirche 92/4 (1995): 434-465.

Aletti, Jean Noël. Essai sur l’ecclésiologie des lettres de Saint-Paul. Pendé: Gabalda, 2009.

Aletti, Jean Noël. “La eclesiología de las llamadas deuteropaulinas. Preguntas y propuestas.” Estudios Bíblicos 68/1 (2010): 53-71.

Aletti, Jean Noël. “Les difficulteés ecclésiologiques de la Lettre aux Éphésiens: de quelques suggestions.” Biblica 85/4 (2004): 457-474.

Aletti, Jean Noël. “Sagesse et mystère chez Paul. Réflexions sur le rapprochement de deux champs lexicographiques.” In La sagesse biblique: de l’Ancien au Nouveau Testament. Actes du 15e Congrès de l’Acfeb, edited by Jacques Trublet, 357–84. Paris: Du Cerf, 1995.

Aletti, Jean Noël. Saint Paul. Épître aux Éphésiens. Paris: Gabalda, 2001.

Armstrong, Karl L. “The Meaning of ὑποτάσσω in Ephesians 5.21-33: A Linguistic Approach.” Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism 13 (2017): 152-171.

Austin, John Langshaw. How to Do Things with Words. Oxford: Clarendon PressOxford University Press, 1962.

Bockmuehl, Markus N. A. Revelation and Mystery in Ancient Judaism and Pauline Christianity. Tubingen: Mohr Siebeck, 1990.

Caragounis, Chrys C. The Ephesian Mysterion. Lund: Gleerup, 1977.

De los Santos García, Edmundo. La novedad de la metáfora ΚΕΦΑΛΗ – ΣΩΜΑ en la Carta a los Efesios. Roma: Editrice Pontificia Università Gregoriana, 2000.

Egg, Markus. “Spatial Metaphor in the Pauline Epistles.” In Spatial Metaphors: Ancient Texts and Transformations, edited by Fabian Horn and Cilliers Breytenbach, 103-126. Berlin: Edition Topoi, 2016.

Esterhammer, Angela. Creating States: Studies in the Performative Language of John Milton and William Blake. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1994.

Gambadatoun, Yémadjro Fiacre Gilles. Connaître le mystere Connaître la sagesse: La γνωσις et l’unité ecclésiale et cosmique en Éphésiens 3,1-13. Roma: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 2020.

Gil Arbiol, Carlos Javier. Escritos paulinos. Introducción al Estudio de la Biblia. Estella (Navarra): Verbo Divino, 2024.

Gil Arbiol, Carlos Javier. “La evolución de la imagen del cuerpo en la tradición paulina y sus consecuencias sociales y eclesiales”. Estudios Bíblicos 68/1 (2010): 73-105.

Ivarsson, Fredrik. “Christian Identity as True Masculinity.” In Exploring Early Christian Identity, edited by Bengt Holmberg, 159-171. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2008.

Köstenberger, Andreas J. “The Mystery of Christ and the Church: Head and Body, ‘One Flesh.’” Trinity Journal 12/1 (1991): 79-94.

Lausberg, Heinrich. Handbook of Literary Rhetoric: A Foundation for Literary Study. Leiden: Brill, 1998.

Lincoln, Andrew T. Ephesians. Dallas (TX): Word Books, 1990.

Low, Maggie. “An Egalitarian Marriage: Reading Ephesians 5:21-33 Intertextually with Genesis 2.” The Asia Journal of Theology 33/1 (2019): 3-19.

MacDonald, Margaret Y. “Colossians and Ephesians.” In T&T Clark Handbook to the Historical Paul, edited by Ryan S. Schellenberg and Heidi Wendt, 380-396. London: T&T Clark, 2022.

Mathewson, David L., and Elodie Ballantine Emig. Intermediate Greek Grammar: Syntax for Students of the New Testament. Grand Rapids (MI): Baker, 2016.

Metzger, Bruce Manning. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament (4th ed.). Stuttgart: Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft; United Bible Societies, 1994.

Mollenkott, Virginia Ramey. “Emancipative Elements in Ephesians 5.21-33: Why Feminist Scholarship has (often) Left them Unmentioned, and Why they should be Emphasized”. In A Feminist Companion to the Deutero-Pauline Epistles, edited by Amy-Jill Levine and Marianne Blickenstaff, 37-58. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2003.

Mouton, Elna. “Reimagining Ancient Household Ethos? On the Implied Rhetorical Effect of Ephesians 5:21-33.” Neotestamentica 48, no. 1 (2014): 163–85.

Mortara Garavelli, Bice. Manuale di retorica (7th ed.). Milan: Bompiani, 2003.

Penna, Romano. Il ‘Mysterion’ paolino. Brescia: Paideia, 1978.

Penna, Romano. La Lettera agli Efesini. Bologna: EDB, 1988.

Perelman, Chaïm, and L. Olbrechts-Tyteca. The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation. Notre Dame (IN): University of Notre Dame Press, 1969.

Porter, Stanley E. Idioms of the Greek New Testament (2nd ed.). Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1996.

Quintilian. The Orator’s Education. Vol. III: Books 6-8. Edited and translated by Donald A. Russell. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press, 2002.

Reynier, Chantal. Évangile et mystère: les enjeux théologiques de l’Épître aux Éphésiens. Paris: Du Cerf, 1992.

Ricoeur, Paul. Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Fort Worth (TX): Texas Christian University Press, 1976.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. Ephesians. Collegeville (MN): Liturgical Press, 2017.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her. A Feminist Theological Reconstruction of Christian Origins. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. “Paul and the Politics of Interpretation.” In Paul and Politics: Ekklesia, Israel, Imperium, Interpretation: Essays in Honor of Krister Stendahl, edited by Richard A. Horsley, 40-57. Harrisburg (PA): Trinity Press International, 2000.

Scott, James M. “Cosmopolitanism in Gal 3:28 and the Divine Performative SpeechAct of Paul’s Gospel.” Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft und die Kunde der älteren Kirche 112/2 (2021): 180-200.

Vrey, Aletta. “The Body Metaphor Reinforcing the Identity of the In-Group in Ephesians.” Neotestamentica 53/2 (2019): 375-393.

Notes

*

Reflection paper.

1

“En Colosenses y Efesios ambas realidades se confunden: la estructura domestica se mete en la ekklêsia, probablemente como mejor modo de resolver los conflictos generados con Pablo.” (Gil Arbiol, “La evolución de la imagen del cuerpo en la tradición paulina y sus consecuencias sociales y eclesiales,” 104).

2

Schüssler Fiorenza, “Paul and the Politics of Interpretation,” 40-57; Gil Arbiol, “La evolución de la imagen

del cuerpo en la tradición paulina,” 73-105; Mollenkott, “Emancipative Elements in Ephesians 5.21-33:

Why Feminist Scholarship has (often) Left them Unmentioned, and Why they should

be Emphasized,” 37-58.

3

Schüssler Fiorenza, Ephesians, 93.

4

Aletti, “Les difficulteés ecclésiologiques de la Lettre aux Éphésiens: de quelques suggestions,” 472.

5

[In Colossians] “Cristo recibe la plenitud de la divinidad […] en Efesios la Iglesia es el πλήρωμα de Cristo; esto lleva al autor a hacer una correlación entre la metáfora κεφαλή σῶμα y el πλήρωμα, en donde σῶμα y πλήρωμα son dos definiciones de la Iglesia que se complementan mutuamente.” (De los Santos García, La novedad de la metáfora ΚΕΦΑΛΗ – ΣΩΜΑ en la Carta a los Efesios, 380).

6

“Creando así un binomio completamente inaudito [cabeza/cuerpo], Col/Ef se ven obligados a asegurar la validez de la imagen; o, dicho en otros términos: deben justificar su uso. Y es esto precisamente lo que han hecho Col/Ef recurriendo a la categoría de misterio.” (Aletti, “La eclesiología de las llamadas deuteropaulinas.

Preguntas y propuestas,”

58).

7

The ecclesial body is an eschatological reality: if the head is risen and glorious, the body that is united to it must also be risen and glorious (Aletti, Essai sur l’ecclésiologie des lettres de Saint-Paul, 184).

8

The complement “one another” (ἀλλήλοις) is explained through the verbs describing the relationships between these parties in Eph 5:21, 25; 6:1, 4, 5. Thus, submitting to one another is clarified by the

submission (ὑποτάσσω) of wives to their husbands, the love (ἀγαπάω) of husbands for their wives, the obedience (ὑπακούω) of children to their parents and slaves to their masters, and the nurturing (ἐκτρέφω) of fathers toward their children.

9

Armstrong, “The Meaning of ὑποτάσσω in Ephesians 5.21-33: A Linguistic Approach,” 152-171.

10

Porter, Idioms of

the Greek New Testament, 64; Mathewson & Emig, Intermediate Gr eek

Grammar:

Syntax for Students of the New Testament, 148.

11

Armstrong, “The Meaning of ὑποτάσσω in Ephesians 5.21-33,” 164-165.

12

Ibid., 170.

13

Aletti, Saint Paul. Épître aux Éphésiens, 269-170.

14

However, as Mouton notes “the text [Eph 5:21-33] primarily challenges us to use its explicit theological thrust as a rhetorical

lens to read against its patriarchal grain and history of reception.” (Mouton,

“Reimagining Ancient Household Ethos? On the Implied Rhetorical Effect of Ephesians 5:21-33,” 181. Italics

by the author).

15

“The relationship between Messiah Jesus and the ekklesia, expressed in the metaphor of head and body,

as well as in the imagery of bridegroom and bride, becomes the paradigm for the marriage relation.” (Schüssler Fiorenza, Ephesians, 93).

16

The marriage relation becomes the paradigm for the relationship between Messiah and ekklesia.”

(Ibid., 93).

17

Ibid., 93.

18

“Since the mid-1980s the majority scholarly consensus has been that the household code texts are rooted

in the Aristotelian philosophical trajectory concerning household management (oikonomia) and political ethics. Moreover, scholars also recognize that these texts are prescriptive and not reflective or descriptive

of reality.” (Ibid., 92).

19

“Este proceso de masculinizacion, análogo a otros grupos

y corrientes, repercutió

tanto en los valores y comportamientos de cada cristiano como en la cristologia

y eclesiologia.” (Gil Arbiol,

“La evolución de la imagen del cuerpo en la tradición paulina y sus consecuencias sociales y eclesiales,” 103).

20

“Esta metáfora tiene una connotación jerárquica en el código doméstico en Ef 5,22-33. Hay una identificación metáforica entre Cristo y el varón (como entre la Iglesia y la mujer) que se establece con el término ‘cabeza’, aplicado al varón/marido y a Cristo, en quienes reside la autoridad; así, el marido tiene la misma autoridad sobre la mujer que Cristo sobre la Iglesia.” (Gil Arbiol, “La evolución de la

imagen del cuerpo en la tradición paulina y sus consecuencias sociales y eclesiales,” 101). Cfr. Ivarsson, “Christian Identity as True Masculinity,” 159-171.

21

“A ella se le pide, expresamente, sumisión a su marido ‘en el Señor’, y se justifica acudiendo a la tradicional jerarquía patriarcal.” (Gil Arbiol, Escritos paulinos, Introducción al Estudio de la Biblia, 583).

22

“La legitimación teológica que los autores de esta carta hacen de la sumisión de la esposa creyente a su marido supone un paso más en el proceso de adaptación de estos grupos de creyentes al nuevo tiempo que están viviendo.”

(Ibid., 585).

23

“Es muy posible que nos encontremos ante otro ejemplo más de doble discurso (público y oculto): el público y aparente parece pedir sumisión a los miembros subordinados según el modelo patriarcal, mientras que el escondido y restringido a los creyentes altera

profundamente ese modelo, instando a los miembros con autoridad a que sirvan a sus subordinados.” (Ibid., 586). Cfr. MacDonald, “Colossians

and Ephesians,” 387-390.

24

“Had Dr. Thistlethwaite instead encouraged me to notice the limitations placed on the metaphor of

husband-as-Christ (that the husband is compared to Christ only in

Christ’s self-giving, self-humbling capacity), I could have trusted her when she assured me that a domineering and emotionally abusive husband had already violated Ephesians 5, so that it was proper for me to leave him.” (Mollenkott, “Emancipative Elements in

Ephesians 5.21-33,” 42).

25

Mollenkott, ““Emancipative Elements in Ephesians 5.21-33: Why Feminist Scholarship has (often) Left

them Unmentioned, and Why they should be Emphasized”, 45.

26

Ibid., 42.

27

This sense of the metaphor is also ambiguous because the husband can hardly be the savior of the wife, while Christ is the savior of both husband

and wife.

28

Does this interpretation leave the exhortation to wives without a coherent rationale? The comparison (ὡς τῷ κυρίῳ) may be incomplete, but not incoherent. It may be incomplete because it does not specify what it means to be subject to another as one is subject “to the Lord” (ὡς τῷ κυρίῳ). However, it is consistent with the use of the metaphor Christ κεφαλή in the passage and in the rest of the letter (as well as in Colossians).

29

The phrase καὶ ἑαυτὸν παρέδωκεν recalls New Testament vocabulary concerning Jesus’ self-sacrifice in

his death (Matt 27:26; Mark 3:19; 15:15; Luke 23:25; John 19:16, 30; Rom 8:32;

Eph 5:2).

30

The three purpose clauses also appear to convey an argumentative progression from the liturgicalecclesial level to the moral level.

31

Indeed, the language of ‘the washing with water’ is likely to have as a secondary connotation the

notion of the bridal bath. This would reflect both Jewish marital customs with their prenuptial bath and the marital imagery of Ezek 16:8–14 which stands behind this passage. In Ezek 16:9 Yahweh, in entering his marriage covenant with Jerusalem, is said to have bathed her with water and washed off the blood from her.” (Lincoln, Ephesians, 375).

32

“La seconda frase finale (v. 27ab) accentua l’allegoria matrimoniale.” (Penna, La Lettera agli Efesini, 238).

33

In addition to the imagery of the body (σῶμα), the wordplay involving the reflexive pronoun (ἑαυτοῦ) provides cohesion to the first part of the argument (vv. 28b-29a), which consists of three anthropological rationales: (1) One loves his own body (τὰ ἑαυτῶν σώματα). (2) Whoever loves his wife loves himself (ἑαυτόν). (3) No one hates his own body (τὴν ἑαυτοῦ σάρκα).

34

“Le v. 29b n’est pas un simple calque du v. 29a. Car le mari chrétien est membre du corps du Christ; tout comme sa femme, il a été lavé et purifié par le Christ, et c’est parce qu’il a expérimenté l’amour (ἀγάπη) du Christ pour lui qu’il peut faire de même. C’est donc de l’amour même du Christ que le mari doit aimer son épouse. Le modèle humain du v. 29a doit donc être lu à deux niveaux différents.” (Aletti, Saint Paul. Épître aux Éphésiens, 285. Italics by the author).

35

Ådna, “Die eheliche Liebesbeziehung als Analogie zu Christi Beziehung zur Kirche: Eine traditionsgeschichtliche Studie zu Epheser 5,21-33,” 434-465.

36

In Eph 5:30, some ancient manuscripts include the phrase εκ της σαρκος αυτου και εκ των στεων αυτου (א 2 D F G M lat Syp Irenaeus). The shorter reading—without this addition—is supported by more reliable manuscripts (P46 א * A B).

This addition suggests the

influence of Gen 2:23.

Metzger’s committee explains it as an expansion “derived from Gn 2.23 (where,

however, the sequence is ‘bone … flesh’), anticipatory to the quotation of Gn 2.24 in ver. 31.” (Metzger, A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament, 541).

37

It is important to note, however, that in Eph 5:28-30 and 31-33, neither the κεφαλή metaphor nor the model of submission appears.

38

A similar observation applies to the head/body metaphor in the context of the human couple. Although husband and wife each possess their own body, they are not strictly speaking one body (σῶμα).

39

Aletti, Essai sur l’ecclésiologie des lettres de Saint-Paul, 179-180.

40

Low, “An Egalitarian Marriage: Reading Ephesians 5:21-33

Intertextually with Genesis 2,” 3-19.

41

This interpretation “is the only one that correctly identifies both the content and referent of μυστήριον, and adequately accounts for the text of the passage

without resorting to unnecessary extratextual explanations.” (Köstenberger, “The Mystery of Christ and the Church: Head and Body, ‘One Flesh,’” 92).

42

Aletti, Saint Paul. Épître aux Éphésiens, 287-288. See also, Penna, La Lettera agli Efesini, 241-243.

43

It is important to note, however, that the author of the letter does not explicitly refer to Christ as the bridegroom or the Church as the bride. This omission underscores the fact that the spousal metaphor is employed only within the specific context and purpose of the passage (Aletti, Saint Paul. Épître aux

Éphésiens, 291).

44

See εἰς with similar value in Acts 2:25.

45

Gambadatoun, Connaître le mystere Connaître la sagesse: La γνωσις et l’unité ecclésiale et cosmique en Éphésiens 3,1-13, 143-154; Aletti, “Sagesse et mystère chez Paul. Réflexions sur le rapprochement de deux champs lexicographiques,”

357-384; Reynier, Évangile et mystère: les enjeux théologiques de l’Épître aux Éphésiens, 105-124; see also, Bockmuehl, Revelation and Mystery in Ancient Judaism and Pauline

Christianity

;

Penna, Il

‘Mysterion’ paolino

; Caragounis, The Ephesian Mysterion

.

46

For Aletti, this use of μυστήριον is entirely paradoxical: “Car il est emprunté à l’Écriture—Dn 2 faisait déjà partie du livres saints—et, comme parole d’Écriture, il notifiait que l’Écriture n’avait pas tout

annoncé, qu’à la fin des temps Dieu dirait des choses nouvelles. Paradoxal usage d’un terme scripturaire, pour justifier l’emploi de termes non scripturaires (en particulier la relation corps/tête)!” (Aletti, Saint Paul. Épître aux Éphésiens, 184).

47

In ancient rhetoric, the metaphor is explained as the shortest form of the comparison. For Aristotle,

metaphor holds a central place: it has the capacity to confer clarity to expression, along with pleasantness and elegance. Its primary function lies in discerning similarities (analogies) between distant things.

Metaphor (1) establishes unexpected connections, (2) condenses expression by omitting certain steps

(like the enthymeme), and (3) creates paradoxes and plays with double meanings (Mortara Garavelli,

Manuale di retorica, 28-29). “In general terms, Metaphor is a shortened form of Simile; the difference is that in Simile something is compared with the thing we wish to describe, while in Metaphor one thing is substituted for the other. It is a comparison when I say that a man acted ‘like a lion,’ a Metaphor when I say of a man ‘he is a lion’.” (Quintilian, The Orator’s Education. III: Books 6-8, §§ 8.6.8-9, 429); see also, Lausberg, Handbook of Literary Rhetoric: A Foundation for Literary Study, §§ 558-564, 250-256.

48

Metaphor is “a condensed analogy, resulting from the fusion of an element from the phoros with an element from the theme” (i.e., it is a fusion of spheres). Perelman & Olbrechts-Tyteca, The New Rhetoric: A Treatise on Argumentation, § 87, 399.

49

Ricoeur, Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning, 66-67.

50

Egg, “Spatial Metaphor in the Pauline Epistles”, 106.

51

Yet my attempt in this book is to bring the two speech-act approaches together […] by demonstrating how the sociopolitical performative and the phenomenological performative interact in specific texts, with or without the author’s awareness that this is

happening.” (Esterhammer, Creating States: Studies in the

Performative Language of John Milton and William Blake, 25). Esterhammer’s study is

based on Austin, How to Do Things with Words.

52

For example, “in Gal 3:28, Paul uses both types of performative utterance as two poles of a dialectic that drives his proclamation of the gospel towards its teleological goal.” (Scott, “Cosmopolitanism in Gal 3:28 and the Divine Performative Speech-Act of Paul’s Gospel”, 193).

53

Vrey, “The Body Metaphor Reinforcing the Identity of the In-Group in Ephesians,” 389-392.

54

“God’s possession” (περιποίησις, 1:14); “new man” or “new humanity” (καινὸς ἄνθρωπος, 2:15; 4:24);

“holy temple in the Lord” (ναὸς ἅγιος, 2:21); “a dwelling place of God in the Spirit” (κατοικητήριον τοῦ θεοῦ,

2:22).

Author notes

a Corresponding author. E-mail: jmgranados@biblico.it

Additional information

How to cite: Granados, Juan Manuel. “The Model of the Church as μυστήριον: Understanding κεφαλή and σῶμα in Eph 5:21-33”. Theologica Xaveriana (2024): 1-24. https://doi.org/10.11144/javeriana.tx74.mcue