Introduction

The first time I went to the Amazon, I was an undergraduate student, halfway through my bachelor’s degree in anthropology. At the time, I wasn’t yet sure what kind of anthropologist I wanted to become, but I knew I needed experience beyond the classroom to figure it out. One day, while sitting on the steps of the sociology building at the Universidad Nacional in Bogotá, my eye caught a small typed announcement on an already-crowded bulletin board. It invited students to intern as rural schoolteachers for a semester in La Macarena, a municipality in southern Meta, at the foothills of an ancient mountain range that had become Colombia’s first protected area. Without hesitation, I wrote down the details and decided to apply. The internship was organized by an environmental NGO, led by a biologist, whose mission was to conserve and protect this important region. To my surprise, not many people found the idea of pausing their studies for a semester to work unpaid in a remote hamlet, deep in a forested region known as the cradle of the Marxist guerrilla organization FARC-EP (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army), as appealing as I did. The eight selected interns —university students from fields such as psychology, philosophy, civil engineering, sociology, anthropology, and zoology— were tasked with teaching children, aged 5 to 14, the basics of primary education while also fostering their awareness of the region’s rich biodiversity and ecological significance.

Most of our students were part of the second and third generations of children born and raised in the region. They were the descendants of peasant families from the Andes who had migrated to this part of the Amazon in the aftermath of the violent bipartisan conflict of the 1950s (Cubides et al., 1989; Molano et al., 1988). After the first weeks living in La Macarena, I realized that the lives of these newer generations could no longer be fully captured by the label colono, a term often used in Colombia to describe mestizo, Amazonian peasant societies (Cubides et al., 1989; Espinosa, 2010; Ruiz-Serna, 2010). Compared to Indigenous Amazonian peoples, colonos were often seen as inauthentic, rootless, and culturally impoverished (Del Cairo, 2019; Harris, 1998; Nugent, 1993, 2002; Raffles, 2002; Ramírez, 2001), an image that, I realized during my time in this region, failed to reflect the cultural complexity and sense of place that these young people and their parents embodied (Ruiz-Serna, 2015).

Each of the interns was assigned to a different hamlet, far from the small village that functioned as the municipal seat. Mine required a three-hour journey down the Guayabero river, followed by another four-hour walk through the forest. In exchange for our work, a local family provided housing and meals during our stay. As teachers in these remote rural areas, our responsibilities indeed extended far beyond the classroom. We became integral members of community life. The school served as the hub for local activities, which meant we were expected to attend meetings, take minutes, write letters, organize fundraising events for community projects, and even mediate conflicts. Our education and outsider status positioned us as influential figures, making it easier, in theory, to achieve our goal of raising awareness among the local population about their so-called predatory economic practices. We were also expected to highlight the many benefits of forest conservation, both for their livelihoods and for the world at large. That, at least, was the underlying premise of our work.

As part of its mandate, the NGO published a book titled Mamíferos de La Macarena, a field guide that, despite its all-encompassing title, excluded the region’s 73 bat species (Morales Martínez et al., 2022) and focused instead on charismatic mammals such as pink dolphins, ocelots, woolly monkeys, tapirs, and peccaries. In addition to providing both scientific and vernacular names, the book described each species’ diet and habits, and even included drawings to help readers identify their footprints in the mud. Each entry was accompanied by a meticulously crafted illustration that, as is typical of field guides, captured the animal’s key physical features in a standardized pose. The NGO successfully distributed the book throughout the region. Every school had at least one copy and I frequently found it in the households I visited. In many ways, the book embodied a pedagogical approach to environmental conservation: fostering awareness and knowledge of one’s surroundings. The core principle behind this approach is simple: you cannot protect what you do not know.

I frequently used the book in my classroom, carrying my own copy wherever I went. I often asked my adult interlocutors which of these animals they had actually seen in the forest. I had set a personal challenge for myself: To spot, at least once, each of the 41 mammal species depicted in the book.

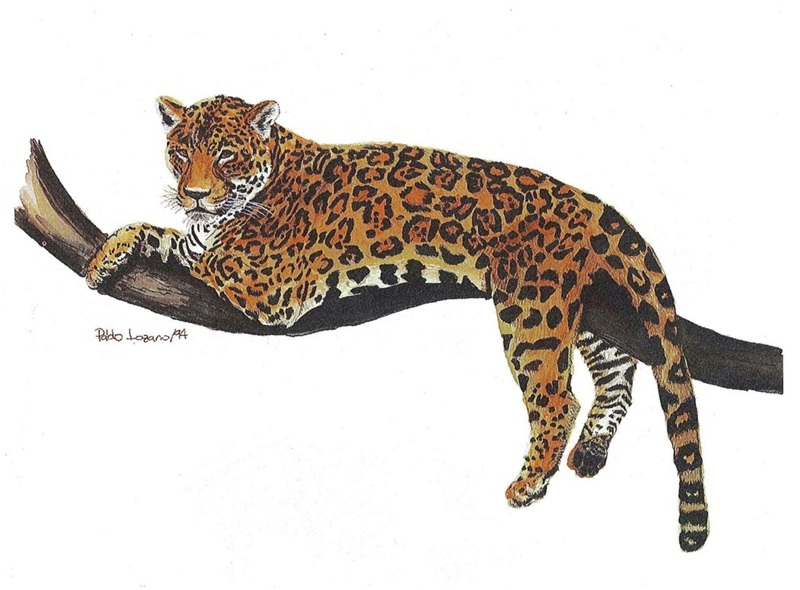

There was one illustration that always sparked reactions. Many of my interlocutors found it inaccurate. Some even laughed, insisting that the animal in the drawing looked nothing like the one they had encountered in the wild (Figure 1).

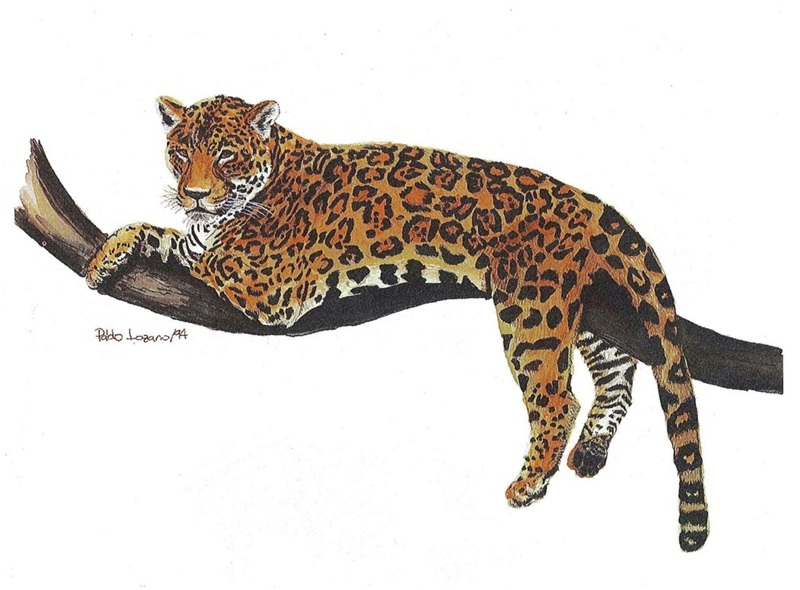

Figure 1.

Jaguar (Panthera onca). Illustrated by Pablo Lozano

Figure 1.

Jaguar (Panthera onca). Illustrated by Pablo Lozano

Source:

Cabrera and Molano (1995).

For many of my interlocutors, especially adult men, this was not an authentic jaguar. The issue was not the accuracy of the illustration. After all, the jaguars’ black spots encircled by an outer ring with a solid black dot at the center were unmistakable, along with their whitish underside, and so were the powerful jaws and oversized paws so characteristic of jaguars. Anatomically, the drawing captured the jaguar’s defining traits. What unsettled these peasants was not the animal’s look but its demeanor. Jaguars in La Macarena, at least those people had encountered, were never found in such a placid disposition. This is not to say they could not imagine a jaguar resting peacefully on a branch. Rather, this depiction did not align with their lived, embodied experiences of a place like the Amazon Forest. Encountering a jaguar requires an extraordinary stroke of luck, at the very least, since it is the jaguar that decides to be seen, not the other way around. Moreover, meeting an unguarded jaguar would demand deep knowledge of both the forest and the animal’s behavior. And for an ordinary human to witness a jaguar in a tranquil, resting state, an almost impossible confluence of factors would need to occur: one that allows a potential prey to approach the Amazon’s apex predator unnoticed, close enough to see it so relaxed. The drawing, in other words, reflected a detached, almost romanticized vision of the animal, more akin to an observation made in a zoo than one drawn from direct encounters in the wild. To my interlocutors, then, the drawing was a strange, almost foreign representation of the jaguar they knew.

Building on this drawing, along with a collection of others I gathered during my fieldwork, this article explores the distinctive ways in which most peasants in La Macarena come to know animals in their forested environments. I contrast their modes of knowledge production with what I call the atomistic representation of living creatures, exemplified by the jaguar and other illustrations found in nature field guides. Atomism, in this context, refers to an epistemological standpoint deeply embedded in Western philosophies, which holds that objective knowledge of the world requires the subject to withdraw from it, even from their own body and embodied experience (Taylor, 1993). A consequence of this atomism, as I will further explain, is that animals can be depicted and understood as detached from their own lifeworlds, a premise that is rightfully challenged by a series of drawings I collected during my work in La Macarena. The text is organized as it follows: In the first section I discuss how everyday interactions with the forest shape the production of knowledge locals attain about animals, and how that embodied and emplaced knowledge informs, in the case of jaguars, an aesthetic perception of animals. I then present a set of drawings depicting birds from the region and I reflect on how they capture the ecological relational tenets that guide peasant practices with the forest. In the last section I briefly discuss how drawings can be approached not just as creative tools for data collection but also as performative devices that unfold new possibilities of theorization.

Knowledge Production

From my very first day in La Macarena, I heard countless stories about the dangers of jaguars. Agile and stealthy, they move effortlessly through the forest, unseen and unheard, stalking their prey with precision and striking with formidable force. Their most frequent targets include capybaras, peccaries, tapirs, and agoutis, but they are equally adept at hunting birds, snakes, crocodiles, and even monkeys. Not to mention their remarkable fishing skills. Despite the abundance of prey in the forest, jaguars are also known to target domestic animals, particularly cattle, occasionally poultry, and, in rare instances, dogs. When a jaguar preys on a dog, I learned, people must exercise extreme caution, as such jaguars lose their natural wariness of humans and may become bold enough to attack. Unlike naturalistic accounts that place humans above or outside the animal food chain, the stories I encountered in La Macarena emphasized human vulnerability in the forest and even within the supposed safety of ranches and homes. When jaguars develop a taste for domestic livestock or human flesh, no place feels entirely secure. Children are consistently warned about the dangers of wandering into the forest alone, and pregnant women are especially advised to avoid solitary walks, as their scent is believed to be particularly enticing to these animals. It was also said that jaguars’ paws function as powerful sensory organs, capable of detecting fear by pressing against a person’s footprints, an ability that further cements their mystique and the deep caution they inspire among those who share the forest with them.

At first, I was skeptical of these stories, assuming that people were merely trying to intimidate a young urban newcomer and discourage me from spending too much time alone in the forest. However, as I delved deeper into the region’s history, accounts of jaguars’ remarkable abilities only multiplied. These stories not only underscored the jaguar’s power but also illuminated the extraordinary skills that many locals had developed to navigate the forest with ease. Following the colonization of La Macarena in the 1950s, one of the region’s earliest economic booms was the fur trade. It was organized around the hunting of giant otters, caimans, ocelots, and specially jaguars. The fur trade was a very important activity throughout the 1970s and until the early 1980s. Jaguars’ pelts used to be in huge demand for the fur coat fashion market after U.S. first lady Jackeline Kennedy wore a coat made of leopard skin in 1962 (Rabinowitz, 2014). Although the jaguar’s fur was less valuable than that of other felines because its hair is quite brittle, it was frequently used for rugs, while its teeth, claws, and paws also found a place in the fashion market. This extractive industry enabled peasants to participate in global markets and generate cash income by relying on a vast, biodiverse forest filled with beings whose bodily parts could be commodified. Unlike other peasant economic activities —such as cattle ranching or the cultivation of maize, manioc, and plantain— which require transforming forests into pastures and gardens, the fur trade and other extractive economies, like the harvesting of rubber, tagua, or cinchona, depended on the continued presence of the forest. These extractive economies demanded an intimate knowledge of place, species distribution, and animal behavior. Success in the fur trade required more than just hunting skills: It depended on the ability to move unnoticed, endure long periods of isolation, and, in many ways, become part of the forest itself.

To describe how these hunting expeditions were organized, I prefer to give voice to don Juan Cabrera, a close friend and the father of five of my eighteen students. Don Juan was still a child when his parents, don Bautista and doña Custodia, among the founding families of La Macarena, arrived in the early 1950s. In those days, don Bautista supported his twelve children by fishing in the Guayabero River, selling his catch wholesale to the Colombian Air Force planes that landed every two weeks to purchase it. As a young man, don Juan turned to another extractive trade: The tigrilladas, hunting expeditions for jaguars and ocelots:

Wherever

we arrived to hunt, we stayed for two or three days. On the day of arrival,

during the trip, we would kill the monkeys we found along the river and those

monkeys were the ones that served as bait for tigers. On the same day we arrived,

the work was divided: two or three would go to make a trail and to tie up the

bait. Two others stayed behind to set up camp and prepare food. The next day,

one would get up early to check the bait, and where the ocelots had eaten, one

would make a camareta [a tree

platform]. At

that time there were already 60 different hunting companies. Companies came

from San José, from San Vicente del Caguán and even from Villavicencio. One could

stay for 15 days or sometimes a month in the forest. Even the one who carried

the least number of skins would bring down 80 or 100 skins. What I didn’t know

is where those furs were traveling. The traders received them here in La

Macarena and when you arrived in town, they received you very well. (Bautista,

personal communication, June 23, 2012)

This account highlights several key aspects of the fur trade’s organization. First, unlike subsistence hunting, this type of hunting was rarely conducted individually but rather in small groups of men organized into expedition fellowships. These fellows coordinated hunting trips with each group trading with a creditor, what don Juan refers to as companies: Merchants who supplied food, guns, ammunition, and tools for the expeditions. The primary goal was to hunt as many animals as possible to repay the advanced credit and generate a profit. As a result, these excursions often lasted several weeks in the forest. They also required a precise division of labor as men had to build trails and establish temporary camps for sleeping, cooking, and processing and storing furs. To hunt jaguars and ocelots, hunters used principally foothold traps and baits. “During the tigrilladas”, don Juan recalled,

there

were many different animals that also used to feed on our baits. The birds of

the forest are like chickens, they also arrive when food is put down: the

paujiles, pavas, gallinetas, guacharacas, torcasitas pechiblancas, panguanas,

chilacues… There is the chilacón, a bird that becomes very noisy when he sees

the jaguar. I used to trust this bird because when he was feeding on the bait,

I could be sure that jaguars would come. When this bird sees a jaguar, he

starts to sing “clu-clu, clu-clu, clu-clu”, and he flies away because the

jaguar is getting close. One begins to pay attention to him, though it is hard

to tell exactly where the little bird is looking. But every time a furry animal

comes, he gives a warning. (Personal communication, July 3, 2012)

In the spots where the baits were placed, hunters had to wait at night in a camareta, a platform built in a tree. To attract jaguars, some hunters even used clay pots or múcuras. By blowing into them, they could produce a whistle, a kind of call that, according to don Juan, lured not only jaguars but also game animals in general, even snakes. Though these sound technologies deserve further exploration, I want to highlight the “multi-species associations” (Kohn, 2013) that hunters relied on during their chores. Hunting in the forest was not just about tracking prey directly but about attentively reading an intricate network of signs left by other beings. Hunters depended on birds, whose alarm calls signaled the presence of large predators; they followed the movements of monkeys, who reacted nervously to unseen dangers; and they even paid attention to the subtle changes in insect sounds, which could indicate disturbances in the forest. This deep attunement to the forest required more than just practical knowledge. It involved developing a heightened sensitivity to the behaviors, rhythms, and interactions of multiple species. It meant understanding the places that animals frequented, recognizing patterns in the landscape, anticipating seasonal and weather cycles, and interpreting the interplay of sounds and scents that revealed the hidden presence of predators and prey alike. In many ways, hunters did not navigate the forest alone; rather, they moved within a web of interspecies relationships, where birds, mammals, and insects acted as sentinels, messengers, and intermediaries. These hunters, then, were not just solitary figures tracking their prey but participants in a broader ecological conversation, one in which humans relied on the superior sensory capabilities and environmental knowledge of nonhuman beings to move, hunt, and survive.

In 1973, jaguars were listed as an endangered species under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), which Colombia ratified in 1981. Nevertheless, jaguars continued to be hunted for their furs until the mid-1980’s, shortly after ocelots were also included in CITES protection.

Knowledge about jaguars, however, is not solely derived from the embodied experience of the forest: It is also shaped through storytelling and everyday activities at home. Consider the following events. On one of the many trips I made after my internship in La Macarena, I visited Jair, who was facing problems in his ranch because a jaguar had killed two of his calves. Though he was able to track the jaguar, he had no success in hunting it down. Wondering why a wild animal with countless prey in the forest was targeting his cattle, Jair spoke with his neighbor Jairo, who told him that the same jaguar had also attacked his herd. As Jair continued his inquiries, he learned that the jaguar had been sighted near other ranches as well, yet oddly, it never attacked the cattle of don Javier, whose ranch lay between Jair’s and Jairo’s lands. This meant that although the jaguar had to cross Javier’s property to reach either Jair’s or Jairo’s ranch, it consistently spared Javier’s cattle. Why would a jaguar behave this way? Were all cattle not equally vulnerable? These were the questions I posed when I first heard the story. After discussing the matter with his family and neighbors, Jair reached a conclusion: the jaguar had been trabajado, that is, bewitched or conjured.

An animal that has been trabajado (worked upon) or rezado (bewitched) is one whose will has been manipulated through rituals and prayers. In the case of the aforementioned jaguar, someone had performed an intervention —some kind of work— to prevent it from attacking specific cattle. Stories like these are quite common. Jairo once told me about a jaguar that had been preying on the cattle of a powerful hacendado (estate owner). For weeks, the jaguar hunted both calves and cows with total impunity and no one was able to track it. In the vast pastures of the estate, cattle from neighboring farms also grazed, yet strangely, the jaguar attacked only the animals belonging to the hacendado. Moreover, none of the neighboring ranches suffered any losses. After repeated failed attempts to hunt the jaguar, the hacendado offered a reward to anyone who could kill it. Everyone knew that this was a worked jaguar, meaning the only way to stop it was to work it a second time. According to Jairo, the hunter who ultimately succeeded had to work the jaguar for several days before finally capturing it using a horse as bait.

A closer look at how a jaguar does not perceive all cattle as equally vulnerable prey reveals a jaguar’s perceptual world open to manipulation. In both cases, the worked jaguars singled out only certain cattle as prey, while perceiving other cattle —such as Javier’s or the hacendado’s neighbors’— as something entirely different. From a human perspective, the cattle remained always the same: They continued grazing, bellowing, and loitering as the boring domesticated animals they tend to be. What changed was the jaguars’ perception. The worked jaguars no longer saw all cattle as food; someone had managed to alter their perception and reality, shifting certain cattle out of the category of prey. If, as scholar Yi-Fu Tuan (1998) once wrote, seeing what is not there or reinterpreting what is present forms the foundation of all human culture, then these stories reveal a world shaped not by singular or unitary sources of mental representation, but by multiple ones where humans are just one actor among many. Instead of an animal “poor in world”, as Martin Heidegger described the existential condition of non-human beings (1996 [1930]), the jaguars of these accounts suggest, on one hand, that representation —the cognitive process of forming images or concepts of external events— is not an exclusively human one, and on the other, human perception of the surrounding world can be deceptive. After all, the jaguars were perceiving and representing cattle in ways that Juan, Jairo or the hacendado could not. While the cattle remained unchanged from a human perspective, the jaguars experienced them differently, perceiving them not as prey but as something else entirely. The ways animals see and interpret their surroundings matter (Kohn, 2013) as they can be incited, for example, to perceive the world in ways that serve human interests. This is precisely what peasants mean when they say that jaguars and other animals can be worked: Their usual patterns of engagement with the world can be influenced by powerful agents capable of engaging in multi-species communication. As a result, animals do not necessarily behave according to what might be considered their “natural” tendencies, they may not see what they are supposed to see, such as equally vulnerable cattle as prey. Animals, to put it in other terms, are not merely part of the world, they also actively shape it and participate in its production.

The existence of powerful people capable of entering into a kind of trans-species field of communication does not interest me as much as the premises on which these procedures and other daily interactions in La Macarena are built: The forest is inhabited by different kinds of other-than-human beings capable of engaging in social relations with humans. A trans-species field of communication in which animals’ will can be redirected, reveals the world as a network of interconnected, subjective agencies, each engaging with each other “through the lenses of their own subjective worlds” (Hornborg, 2001, p. 125). Like many other caboclo and peasant societies in the Amazon, peasants in La Macarena hold that animals possess agency, sentience, and personhood, albeit to varying degrees across different species (Galvão, 1951; Ruiz-Serna, 2010, 2015).

It is on account of these different ways of knowing jaguars and of recognizing them as potential knowledge producers that the friendly and serene jaguar of the drawing was hardly recognized as the kind of sylvan feline that stalks human and non-human prey. By emphasizing the embodied experience of the forest as the primary source of knowledge about animals, I am not suggesting that my interlocutors are incapable of abstraction or of detaching their knowledge from the embeddedness of place. My aim is to highlight the reverse: the set of simplifying premises and detached operations that enable people, particularly in post-domestic settings, to recognize the jaguar in the drawing as a generic type rather than as a being deeply entangled in specific relational contexts. Let me illustrate this point.

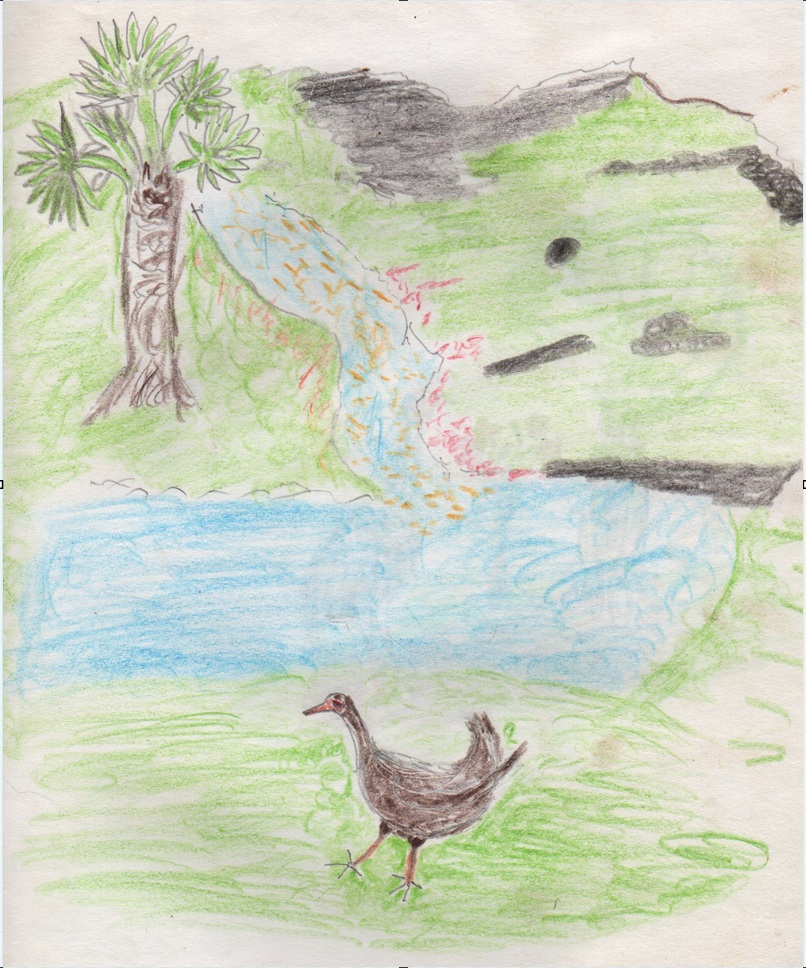

Birdscapes

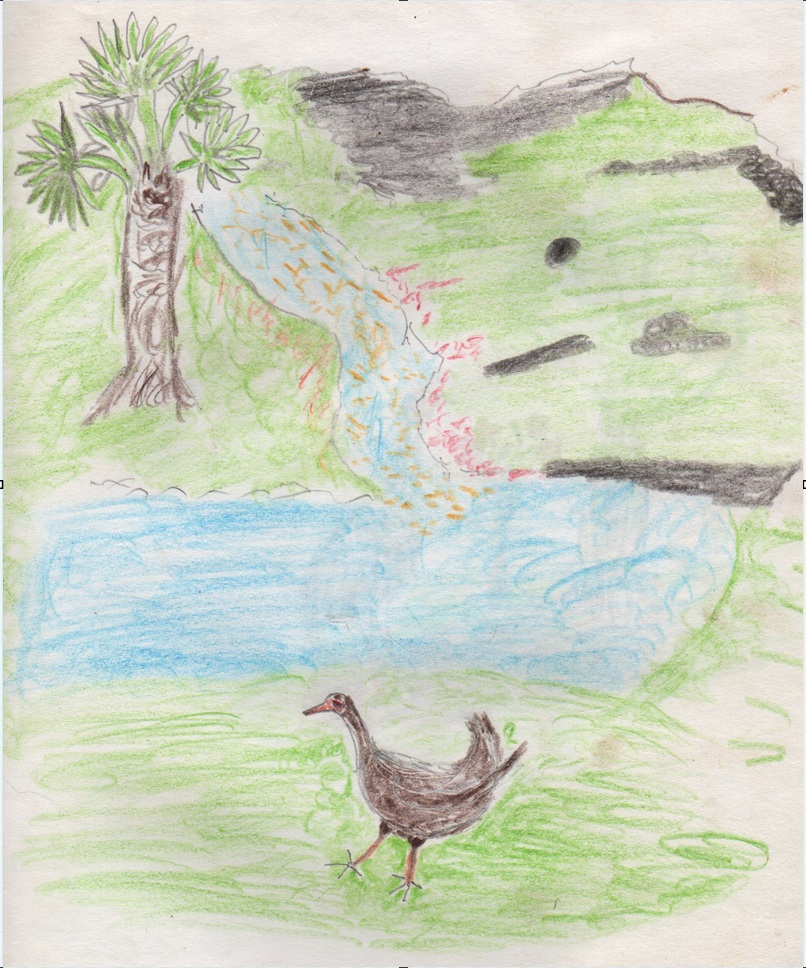

During one of my fieldwork stays, I asked don Juan to draw some birds for me. I believed that his experience as a hunter and his deep knowledge of the forest could add texture to my ethnographic descriptions of human-animal relations, which I was particularly interested in at the time. I made a notebook using unused sheets from one of my diaries, binding them with cardboard from empty boxes as a cover. I provided him with colored pencils and simply asked him to draw any birds he wanted. He took on the task with enthusiasm, spending his evenings working on the drawings and warning his children not to touch his tools or notebook. Three weeks later, he gifted the notebook back to me. I was astonished by the level of detail in his illustrations and by what they revealed (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Chilaco

Figure 2.

Chilaco

Source:

Illustrated by Juan Cabrera.

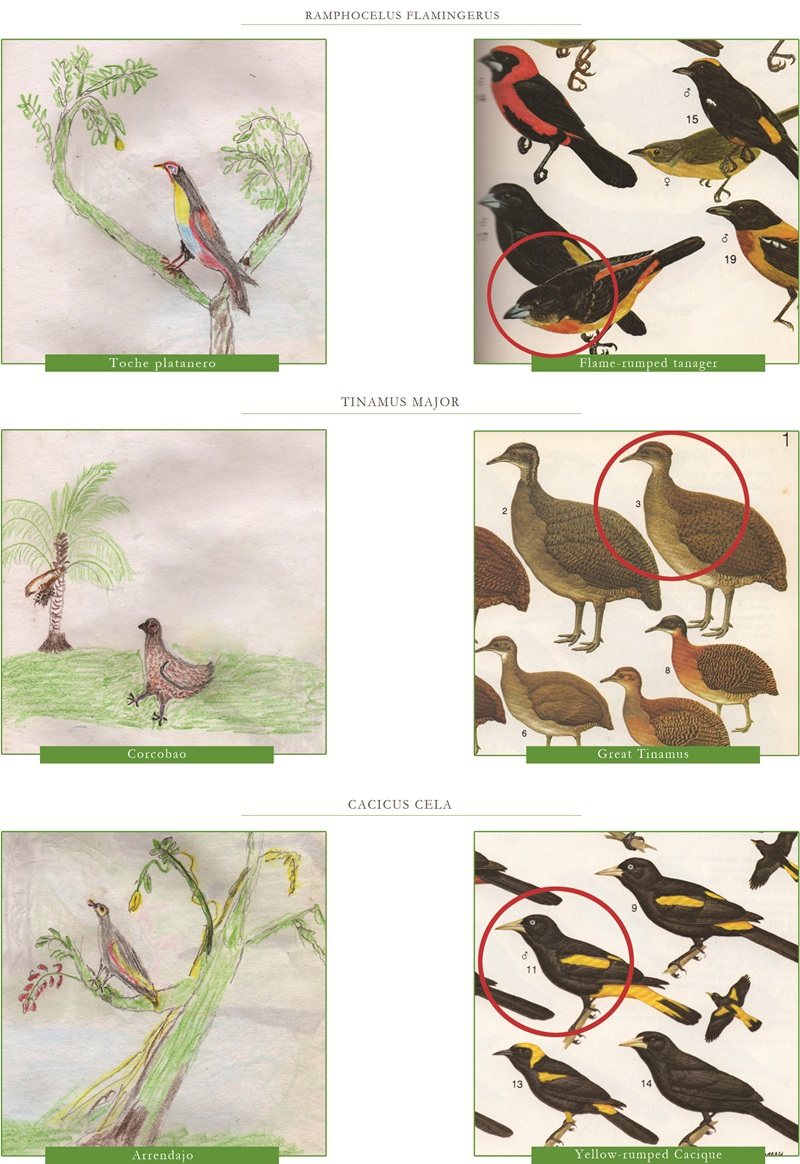

Figure 3.

Mochilero and gallineta

Figure 3.

Mochilero and gallineta

Source:

Illustrated by Juan Cabrera.

The first depicts a chilaco, a bird called Aramides cajaneus in the binomial nomenclature used in biology. It is also called grey-cowled wood rail in English and chiricote in some other Latin-American regions. While its vernacular names in Spanish refer to its call (chi-la-clo-clo-clo), the scientific name points out to its resemblance to another set of crane-like birds (Aramus) and to the capital city of French Guiana (Cayenne) (Hilty & Brown, 1986). In the name by which the bird is identified in La Macarena, the chilaco demands a particular sensorial engagement from us, one that privileges hearing over sight, highlighting how in different systems of classification animals emerge as socially and historically contingent beings rather than fixed, pre-existing entities. The second drawing depicts a mochilero, a bird known for constructing hanging woven nests that can exceed 125 cm in length, alongside a gallineta de monte, a generic name used in La Macarena for ground-dwelling, tailless birds whose plumage blends seamlessly with leaf litter.

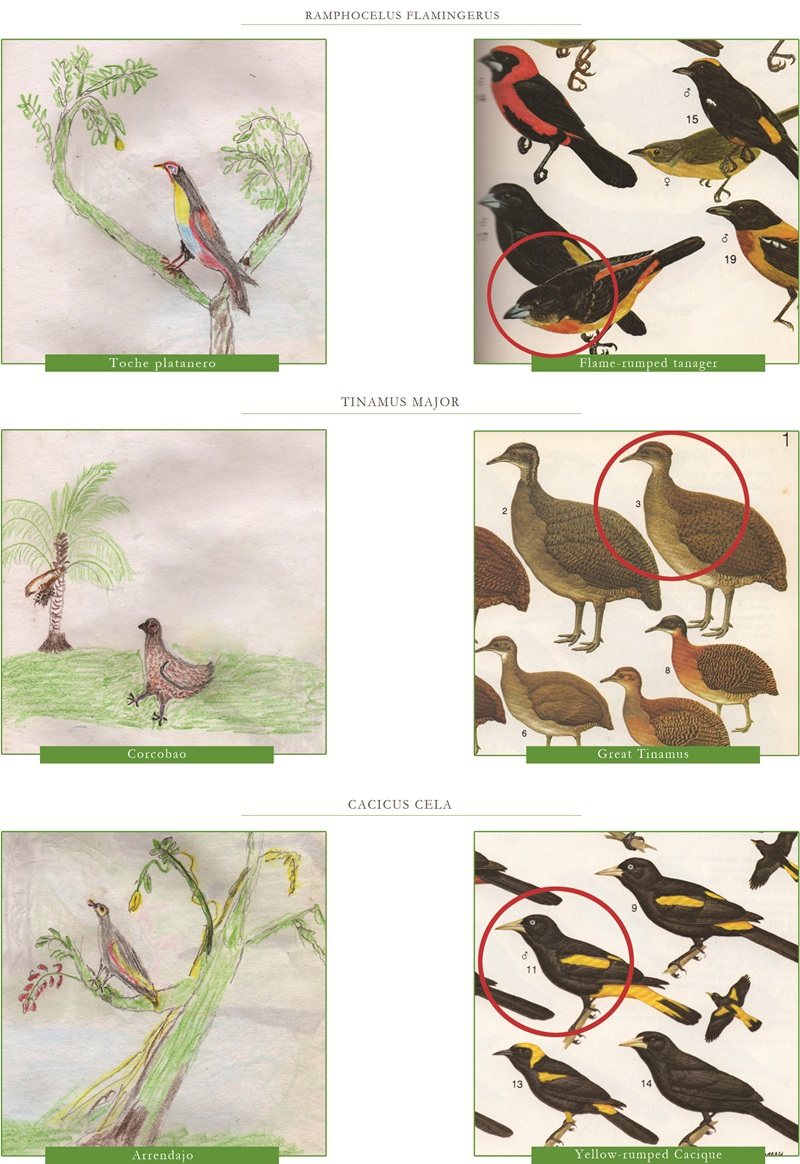

Beyond the figurative elements of these images, which render visible a set of implicit tenets about people’s perception of animals and their environments (an aspect I will discuss later), don Juan’s drawings also serve as a form of autobiographical record. The chilaco, for instance, is placed near a morichal —exactly the kind of swampy forests these birds inhabit— at the foothills of a tepui, one of the steep-sided, table-top mountains that make up the Serranía of Chiribiquete, a place don Juan visited in his youth while working in the tigrilladas. The drawing, in this case, plays a mnemonic function, one that in the very act of creation demands a form of contemplative thinking from don Juan about his past while also allowing him to connect with place. Years later, as I sought to understand the kind of ecological knowledge embedded in these drawings, I came to recognize his attentiveness to the currents of activity in the environment, one that reveals a philosophical depth and sensorial orientation I had been unable to verbally grasp during my interviews with him or with my other local interlocutors during my initial fieldtrips. To help readers appreciate this, I have placed some of don Juan’s drawings alongside some illustrations from a professional bird field guide (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Juan’s drawings alongside

some illustrations from a professional bird field guide

Figure 4.

Juan’s drawings alongside

some illustrations from a professional bird field guide

Source: comparison between Hilty,

S. & Brown, W. (1986) and personal archive from the author.

The birds in the left column were all drawn by don Juan, while those in the right column come from a guide to the birds of Colombia authored by ornithologists Steven Hilty and William Brown (1986). Each drawing depicts the exact same species, yet these two sets of drawings differ in the technique and style, as well as in the kind of features each one emphasizes. Typically, in field guide illustrations the light source is positioned in the top left corner, with the bird oriented toward the light to ensure that the patterns and colors on its breast remain well-lit. Additionally, shadows are minimized to prevent any confusion with the bird’s natural markings and coloration (Laws, 2015). Although don Juan’s drawings do not capture the physical features of each bird with the same precision of the field guide, they situate every species within a specific environment, offering clues about its natural habitat and even highlighting particular trees associated with its behavior. In contrast, the illustrations in the ornithology manual resemble the abstract jaguar we discussed earlier: Birds are depicted in isolation, detached from any environmental context, almost as if suspended in an empty space. Though the deemphasis of background details is a common convention in scientific anatomical drawings to ensure that crucial physical features of the specimens remain unobscured (Anderson, 2017; Laws, 2015), the arrangement of the birds, often in profile allowing viewers to compare proportions, suggests a carefully curated collection of embalmed specimens rather than a dynamic representation of wildlife.

Since the publication in 1678 of what is now considered a foundational text in ornithological illustration (Willughby & Ray, 2020), the visual atomistic depiction of birds has persisted. Most contemporary field guides, including three recent ones on the birds of Colombia (McMullan, 2018; Ayerbe Quiñones, 2019; Hilty, 2020) continue to follow a format rooted in natural history and anatomical drawing. Informed by Enlightenment ideals of objectivity, order, and classification (Roberts, 2024), this approach abstracts species from their ecological settings to emphasize form over context, thereby facilitating standardized identification across observers. While field guide illustrations are undoubtedly useful for identifying birds based on their phenotypical characteristics, they capture little of the features that peasants consider essential for their identification: Sounds, smells, species associations, landscapes. Don Juan’s drawings, by contrast, reflect an ecological way of knowing, one that includes the plants and fruits birds rely on, their habitat, and even the other bird species they interact with. Both set of drawings aim to represent observed birds, but while the field guide seeks to depict the species that is ‘out there’, don Juan pays attention to how birds live and relate with their environments.

I can extend this comparison by arguing that one set of drawings represents the atomism of biological knowledge, where species are self-contained, clearly delimited entities, while the other embodies the relational aspects of peasant knowledge, in which birds and their surroundings are not considered complete separated domains (Ingold, 2006). When birds are presented as a collection of bodies lying in a white empty background, animals are seen as beings that can be understood in isolation from their living environments, emphasizing the idea that each organism is delineated and contained within a perimeter boundary (Descola, 2017). In don Juan’s drawings, birds do not simply move in an environment that works as a background, rather birds and their surroundings are integral to each other. I can also suggest that these drawings reflect distinct aesthetic experiences of nature or that they exemplify fundamentally different understandings of life itself. Following Jasamin Kashanipour (2021), I understand aesthetics not merely as the appreciation of beauty but as a form of knowledge rooted in perceiving, feeling, and sensing. After all, the ancient Greek word from which “aesthetics” derives means “perceive, feel, sense” (Kashanipour, 2021, p. 87). In the perspective embedded in don Juan’s drawings, beings do not simply occupy the world; they dwell on it. The environment is not an inert backdrop over which living things move like actors on a stage (Ingold, 2006). Instead, animals and their surroundings are inseparable, co-constitutive elements of a shared world. In contrast, the field guide illustrations depict birds as discrete species independent of the ecological networks they are part of, reflecting an atomistic perspective in which organisms are studied as abstracted from the relationships that sustain them. Don Juan’s drawings situate birds within trees or plants, visually reinforcing a relational philosophy in which each bird is a node in a wider web of connections. Rather than merely classifying the bird as a species, his drawings portray it in relation to the larger world it helps shape.

I might also argue that the atomistic representation of birds is an impoverished way of, literally, seeing animals. This is an impoverished way of seeing that also impoverishes the world. To be sure, none of the set of drawings are animal portrays in the strict sense. Rather, both are simplified abstractions of actual individuals, both portray an idealized type in some kind of conventional posture. For example, in his book The Laws Guide to Drawing Birds (Laws, 2015, p. 3), naturalist and artist John Muir Laws makes it clear that field guide illustration is an attempt to average characteristics of many individuals into a “typical bird.” The portrayed birds do not really exist. Rather, each illustration is an attempt to blend anatomical features between individuals. The same can be said about don Juan’s drawings: They portray an animal type, not a token. But the simplifications are of different order. One of them does so by paying attention to the ecology in which the bird participates, while the other just overlooks that world. While don Juan simplifies birds’ complex physical features, he enriches their setting; while the field guide pays too much attention to forms, colors, and shapes of anatomical characteristics, it ends up impoverishing birds’ world.

Don Juan’s drawings would help me strengthen the argument that ideas about animal personhood, agency, and deep interconnections within the environment do not stem from the mere projection of preconceived beliefs about the natural world. Rather, such ideas emerge from a bodily and sensory relationship with a place that, like the forest, is peopled by multiple sentient and agentive selves. In this sense, more than reflecting pre-existing ideas about animals, I suggest the drawings enact a particular version of nature, one that allows the authors to portray legible animals and the viewers understanding them as plausible. Along these lines, I do not think that one way of representing birds is inherently better than the other. Rather, I believe that by the zooming in and zooming out of different details, both ways of representation unlock different properties of animals and life while foreclosing others. For instance, the drawings from the field guide are particularly useful for species identification, offering a standardized, decontextualized view that highlights anatomical features in a way that allows for precise classification. They cater to a scientific framework that seeks to organize biodiversity into discrete, comparable units. In contrast, don Juan’s drawings emphasize the ecological and experiential dimensions of peasant knowledge. His illustrations do more than depict species; they convey how birds dwell in the world. In this sense, these two modes of representation might reflect different epistemologies: One that isolates and categorizes, and another that integrates and contextualizes. Both have their place as the social products they are, but recognizing their differences helps us appreciate the worlds drawings might unlock, as well as the multiple ways of knowing and engaging with the living world that they entail.

The drawings do not simply reveal a different kind of nature but enact it, enabling both a particular epistemic framework for the creation of these drawings and a specific sensory inclination to interpret them. In this sense, drawings possess a performative effect too: They do not simply depict animals through an imagistic language but constitute them, participating in their coming-into-being. It is clear that through the sheer act of creation, the makers bring a world into existence. Yet, the performative qualities of these drawings extend to the receivers as well. As philosophers John L. Austin (1962), Mikel Dufrenne (1973) or Gernot Böhme (1993) have argued in relation to the aesthetic possibilities of the work of art, perceiving or engaging with an image is not a passive act but one that completes the work. The observers, whether an ethnographer reflecting after fieldwork on the nature of the animals he had witnessed, an Amazonian peasant, or a bird lover identifying birds in the field, do not merely look but actively interpret, animate, and situate the animals within their own sensory and epistemic frameworks. To be clear, each set of drawings unlocks different properties of animals and their surrounding worlds. Even a tool for the identification of apparently transcendent beings like a field guide might help us cultivate what Anna Tsing (2010) describes as an “art of noticing”. She portrays classification not just as a neutral organizational tool but as a way of perceiving the diversity of life. As a practice of attentiveness, noticing might reveal the hidden rhythms, interconnections, and vitality of more-than-human worlds, turning classification into a way of inhabiting and sustaining multispecies companionship, rather than simply labeling it. A field guide, when used as a companion in the field, can accomplish this art of noticing: Rather than merely imposing order from above, it might convey the practice of attunement of perception: Attunement to the birds, of course, but also to place and to one’s position in that ecological network. In this way, when classification is accompanied by noticing, we are also learning to listen, to smell, and to become entangled in ecologies, not just mentally ordering them. In other words, a world is also made in the exchange between creator and observer as the reception of the drawings activates new possibilities for the animals they depict. The drawings, then, distribute agency, and in different degrees. But not only between creators and observers, as I have just noted, but also within the animals themselves and the worlds they bring into being. This is why I contend that no kind of drawing is inherently superior to another, rather each unlocks certain properties of the world while inevitably foreclosing others. While in the field guides we are freed from the obligation to situate living beings in relation to one other, don Juan assumes that obligation with great care, compelling us to see the ecologies these animals co-shape. Whether inviting us to classify, separate, associate, contain, or encompass, all these drawings invite us, nonetheless, to cultivate a mode of attention that urges us to not neglect that to which one should cling (Latour, 2015).

Concluding Remarks on a Killing Drawing

Figure 5.

Raudal de Angosturas I

Figure 5.

Raudal de Angosturas I

Source: Photo

taken by the author.

The last time I visited don Juan, he was at his house on the banks of the Guayabero River. He had moved from the hamlet where I first met him as a teacher to a piece of land at the lower end of El Raudal, a striking section of the river where the water’s flow is dramatically altered by a sudden drop in elevation, creating powerful and rather dangerous rapids. Towering rock formations flank both sides of the river for approximately 300 meters, forming a natural corridor of stone and water. At the lower end, the rocks are covered in petroglyphs, ancient carvings that, like many found across the Amazon basin, mark significant ecological and ceremonial sites. This place is rich in fish, making it a prime fishing spot all year long. That is precisely what don Juan, wearing a t-shirt with the number 9 on his back, is doing in the image alongside his brother Marcos, and Andrés and Felipe, two of his sons (Figure 5).

While the river carves its way through the rugged landscape —lush vegetation on one side, massive rock walls shaped over millennia by the relentless current on the other— the scene is interrupted by a warning scrawled on the rock. The words “PROIBIDO PESCAR EN EL CAJON” (Fishing Prohibited) stand out in blue paint, accompanied by the unmistakable symbolic trope of danger and the inevitability of death: A human skull, crudely drawn, with two unfinished bones (that rather seem ears) crossing behind it. The drawing is clumsy, almost childlike rendering: Lines uneven, proportions off, all of which creates a stark contrast with the gravity of the warning, almost turning it banal. But the message is clear: disregarding it could have fatal consequences. Yet, the very way it is inscribed on the ancient rock, with an unsteady hand and an almost careless stroke, makes it feel more unsettling: Less like a formal prohibition and more like a foreboding sign left by those who, during decades, heralded and routinized violence in La Macarena. More than a simple warning, this defacement becomes a threat once one considers its authorship: FARC-EP (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

A threat

Figure 6.

A threat

Source: Photo taken by the author.

The contrast between the river’s abundance of fish and the stark warning sign highlights the fragile balance between opportunity and risk in this place. A precariousness that, for don Juan, ultimately tipped toward the fatal. In July 2016, he was killed by the very people who painted the rock because, according to the members of that criminal army that had claimed a monopoly over fishing in these waters, his livelihood disrupted the river’s ecological balance. A justification as callow as the crude skull scrawled on the rocks.

As I have been arguing, drawings do not simply depict worlds: They make them, hold them together, and sometimes unravel them. They do so not from a position of stability or permanence, but from within the contingent and often fragile threads that bind beings and their relations to their graphic representations. Don Juan’s drawings, like the skull on the rock, do not merely enact worlds in motion, they also register the instability of its foundations. In this sense, drawings are epistemically productive but also politically and ontologically risky: They expose the fragility of the very relations they strive to preserve. Attending to these drawings, I think, is therefore to engage with a form of knowledge that is embodied and inseparable from carnality and mortality. It is to confront how world may quite literally hang from a line, and how, as my friend’s death makes clear, life may cling to it, rely on it, or be what is at stake within it.

Most ethnographic literature on drawings describes their use as another technology of documentation, one that, due to its pre-cognitive and pre-verbal potentiality, reveals the emplaced and embodied experience of the ethnographer (Hodson, 2021). In this context, much emphasis is placed on the researcher as the one who draws and on how their drawings make visible a phenomenological self that can be “accounted for within anthropological analysis” (Hodson, 2021, p. 1). Here, however, by privileging the use of drawings in the hands of our interlocutors in the field, I aim to shed light on their potential not only as reliable tools of documentation but as catalysts for ethnographic encounters (Hendrickson, 2008) and ethnographic reflexivity. In this sense, drawings harness their own “range of potential relations, methods and theories” (Wright, 1998, p. 21), becoming what Ana Afonso (2004) describes as “devices to render visible implicit meanings” that emerge not only from the interviews but also from the conversations with and practices of our interlocutors (Wright, 1998, p. 86).

In my attempt to draw out the knowledge contained within don Juan’s drawings, I have realized how much they matter in terms of their potential as anthropological texts. Paraphrasing Donna Haraway (2016), when drawings are used as a means of thinking through and with, they reveal why it matters what stories and practices make worlds and what worlds, in turn, nest these practices. But beyond their inherent worth, I feel that drawings also matter because they form and give shape to matters, because they too make materials. A fact I am compelled to accept with visceral force every time I look at the cardboard notebook illustrated by my dear dead friend.