Migration has become a prominent topic in both academic circles and public discussions, particularly in media, which have played a significant role in shaping the highly politicized and visualized image of the “migrant”. However, this media-driven portrayal of migrants often overlooks essential aspects of migration, leaving them underrepresented or ignored (Schielke & Graw, 2012), what is typically sidelined in public discourse are the personal experiences of migrants, their imaginative worldviews, and the complexity of their individual stories. In this article we argue for the development of more respectful, ethical, and collaborative practices that engage protagonists in both the ethnographic and creative processes—allowing them to decide which stories to tell about themselves and how to tell them. As such we have given here priority to our collaboration and to the examination of the practice of animation as an ethnographic tool particularly well suited in tracing processes of memory making and storytelling.

1

In the past two decades, there has been a growing focus on exploring people’s inner experiences and imaginative worlds, particularly within social sciences and humanities. This is particularly relevant to the study of migration, where dominant push-pull models have long reduced complex motivations to economic logics, overlooking how personal imaginaries, expectations, and lived experiences shape migratory journeys (Schielke, 2008, 2015; Jackson, 2008, 2012, 2013; Gaibazzi, 2012; Cangiá & Zittoun, 2020). This type of research aligns with scholarly work by visual anthropologists that emphasizes sensory knowledge, memory, and imagination, often expressed through non-verbal forms (Hogan & Pink, 2010; Cox et al., 2016). Ethnographic collaborations with artists have promoted participatory frameworks, expanding traditional methods like interviews and observations to include more engaged types of research exchange through creative practices and collaboration, particularly in studies of health, movement, and social exclusion (Radley & Taylor, 2003).

Though scholars in both animation and anthropology have begun to appreciate the connections that can be drawn between the two disciplines (Silvio, 2010; Callus, 2012; Moore, 2015; D’Onofrio, 2017a, 2017b, 2025; Morelli, 2021; Hamdy & Moll, 2024) the use of animation within the practice of anthropology is still at its very beginnings.

The two-year ethnographic research project that underpins this paper—enabling collaboration between a visual anthropologist, a professional animator, and research participants—remains a rare and distinctive example.

2

The Research Project and our Collaboration – What Brought us Together

Between 2012 and 2014, Alexandra D’Onofrio carried out fieldwork for her PhD with three Egyptian young men who had migrated to Italy by crossing the Mediterranean Sea. She invited Mohamed Khamis, Ali Henish, and Mahmoud Hemida to take part in creative processes that explored the relationship between their experiences of crossing, their memories, and their imaginative lifeworlds (Jackson, 2012) as they shaped their autobiographical stories amid moments of profound change. Through theatre improvisation, co-devised storytelling, participatory photography and animation, and collaborative filmmaking, they undertook an investigation that was simultaneously methodological, epistemological, and existential. The exploration through audio-visual methods unfolded shortly after a pivotal moment in the lives of the research participants. In September 2012, an amnesty decreed by the Italian government allowed them to legalise their status after living undocumented in Italy for nearly a decade. With their newly obtained residence permits, Mohamed, Ali, and Mahmoud expressed a desire to return to the places where they had first arrived in Italy and to film these journeys as part of the ongoing collaborative research. In co-creating narratives and images about their experiences of crossing and arrival, participants found space to reflect on defining aspects of life as undocumented migrants — including their ‘criminalisation and infantilisation’ (Gatta, 2018), a pervasive sense of ‘stuckedness’ (Lems & Tošić, 2019), and the feeling of a ‘future-lost’ (Khosravi, 2018). As many years had passed since they had set their foot for the first time on Italian soil, returning to the places of arrival under changed legal circumstances enabled them to use their voices and create new images to recover a sense of agency over that part of their lives and provide new meanings to their experiences all together. This marked their first return to the sites of disembarkation since their initial crossings.

During the collaborative filmmaking process, Alexandra encouraged them to narrate through on-the-spot improvisation in front of the camera and to photograph locations that held personal significance. These embodied recollections were shaped not only by memory, but also by imaginative absences—gaps between past experiences and present places—which were made palpable through a deliberate shift in documentary mode. This approach invited research participants and our future audience to engage imaginatively with what could not be directly shown or told.

The final phase of the creative process focused on exploring these imaginative gaps through participatory animation (D’Onofrio, 2017a), developed in collaboration with Francesca Cogni—a professional illustrator and animator, who already had an established relationship with Mohamed, Ali, and Mahmoud from previous projects. Francesca’s contribution enriched the aesthetic and methodological dimensions of the research with insights from her own long-standing practice. Since 2009, her animated documentaries (including 42 – Storie da un edificio mondo [2009], Sui bordi – dove finisce il mare [2013], Es war einmal in Café Kotti [2016], Neviaro [2017], and Tirhas [2017]) have explored the interplay between stop-motion animation and documentary imagery. Her work particularly investigates drawing and animation as tools for observing not only tangible reality (Nasim, 2014) but also the more elusive terrains of dreams and imagination—cultivating a mode of engagement that respects both privacy and intimacy, while fostering a meaningful connection between the act of drawing and the surrounding context.

The practices of ethnography and of animation worked side by side in this collaborative exploration: Mohamed, Ali and Mahmoud became involved in a process of meta-animation, where reflections and theoretical hypotheses emerged during the practice and in constant dialogue between the two of us and the research participants. We both conceive of collaborative creative practices as central to providing an ethical framework to the way we engage with others’ sensitive and intimate stories in our research through ethnography, drawn and moving images. Collaboration is a requirement for anthropological knowledge that claims to be accurate and respectful of people involved. Allowing participants to shape the project’s direction acknowledges their expertise and moral agency in representing and theorising about their lives (Irving, 2007).

Our methodological experimentation with participatory visual practices opened diverse avenues for expressing thoughts and feelings, allowing participants to complement, challenge, or resist our assumptions. This not only fostered more genuine and meaningful communication but also contributed to a redistribution of authority within the research process. As Pink (2011, p. 450) notes, participatory visual methods can enable “the experiences of those who are normally invisible to be seen and their voices and feelings to be heard” (see also Cox et al., 2016, p. 16). In particular, when animation is approached collaboratively, it allows the various actors involved—participants, facilitators, researchers, and artists—to share a creative process in fieri. This exchange actively questions the conventional power dynamics of documentary filmmaking, making space for alternative forms of authorship, representation, and collaboration.

Animation and metaphorical storytelling allowed Ali, Mohamed, and Mahmoud to reshape their stories as they chose, masking or transforming them in creative ways. Our collaboration demonstrates how animation can expand ethnography’s scope, enabling a creative reimagining of reality. This approach allows us to challenge official narratives and social hierarchies, dissociating analytical distance from truth, while engaging participants as co-researchers in the ethnographic process. Memory and more recently reverie and imagination have become central to ethnographic practices that intend to investigate people’s experiences and identities, but the challenge that anthropologists face when carrying out this type of fieldwork is how to bring events of people’s past into life, when there is no independent access to people’s interiorities, past experiences, memories and imaginations (D’Onofrio, 2017b). By experimenting with drawn animation, we argue that a more collaborative and interdisciplinary approach to memory offers innovative insights into its multifaceted processes where memory itself emerges, is recreated and disappears in the acts of remembering, and forgetting. Finally, animated documentary enabled our research participants to portray what is generally invisible to the naked eye, by allowing us to gain access to certain internal spaces of being, intangible memories and imaginations, thanks to its ability to permeate reality (Wells, 1998).

This paper is an outcome of the reflections that emerged as we observed memory being imaginatively animated, and becoming ‘alive’, during the creative process that we all shared.

The method and its relationship to memory

Stop motion animation is an analogic and handmade technique that creates the illusion of movement through a series of photos where (mostly) inanimate objects are slightly moved in each picture. The flow of images makes them move on the screen. Any object can be animated in this way, and also pieces of papers, drawings or even living beings: the core of stop motion is to progress frame by frame. Due to the length of the process and the effort required, stop-motion animation usually requires a lot of planification, the storyboard that guides the animation is really strict, each frame is numbered, and it is never open to improvisation.

However, at the core of this project—and of this article—is a rethinking of animation, not as a visual tool for transcribing experience, but as a method for processing it. Francesca proposed an approach centred on animating through drawing, deliberately without a storyboard. This creative strategy kept the process open to improvisation, allowing for an exploration of possibilities and a mode of thinking by doing. The process of drawing served as a catalyst for what followed, propelling memory forward and guiding the development of narrative. In this approach, memories took shape through the unfolding animation, generating a dynamic process in which recollection was continually revisited and reshaped in real time - each line drawn contributing to the evolving story.

After extensive discussions over which animation technique would best support the exploration and representation of memory, we chose the ‘paint on glass’ method—an approach Francesca had already been experimenting with. Mohamed, Ali, and Mahmoud painted their figures directly on glass over photographic backgrounds, layering coloured paints to create a fluid, dynamic quality in their drawings.

We created a light box setup. This consisted of a drawer, a small table lamp, and a glass frame, under which each black-and-white photo was placed. This arrangement enhanced the visual contrast of the animated colours, while the transparency of the photos of real locations provided a continuous reference for their drawings. A still camera, mounted on a tripod and directed at the frame, was linked to a computer with software that automatically triggered the camera to take a shot when the frame was ready. The captured image would then be imported into the software’s timeline, allowing the animator to see their drawings develop gradually, one frame at a time.

An insightful explanation of the process of animation as activation of memory comes from a description by Alexander Schellow, who works re-constructing the memory of reality by drawing:

The drawing

influences the memory at the moment it is recalled, so that it can imprint

itself on the drawing: facing the surface of the paper, I first place a dot,

whose sight stimulates my memory; in response, I make another dot, which begins

to trace a form linked to this memory - and so on. The inscription of the work

of memory that results from this can be read and understood as a realisation

rather than a representation of the memory.

3

(Schellow, personal communication, 2011)

What cannot be verbalised, finds a shape thanks to the freedom of association given by surrendering to a state of trance while animating, which unleashes the unlimited possibilities provided by the process of drawing. In this process the animation is guided by the act of progressive discovery as memories are drawn to surface and discovered.

In his book On drawing, John Berger suggests that a drawn image holds within it the act of looking, encompassing time and the experience of exploration (Berger, 2005). We would like to contend that animation without a storyboard contains the experience of remembering. The repetitive act of producing a sequence of drawings that are made and deleted and recreated again puts the animator in a suspended time and state of mind which unlocks the possibility to explore deep layers of memories. The hand that animates functions like a seismograph, capturing the ebb and flow of thoughts and memories. Drawing and animating are deeply embodied, physical acts; the animator’s body is fully engaged in the space and time of the process. In a letter to his son Yves, Berger (2005, p. 124) asks, “Where are we when we draw?” prompting a reflection on whether we are located where we are physically drawing or within the space being drawn.

Revisiting places of arrival—which was made possible thanks to a change in le Berger suggests the act of drawing unfolds over time, potentially being “more about becoming than being” (Berger, 2005, p. 124), rather than fixed in space. Legal status - reawakened the participants’ embodied memories in specific ways: it allowed them to reclaim this part of their stories and reflect on them with the insights and nuances they could only recognize in hindsight from within a very different existential perspective. Through animation, memory took on a new form, as Mohamed, Ali, and Mahmoud spent days in a dimly lit room, immersed in the repetitive rhythm of “draw–wipe off–draw.” The immersive experience of remembering without having a storyboard is enhanced by this kinaesthetic experience of animation which creates a perception of reality as it is recomposed through progressive fragments (Lefkowitz, 2015). For the animator, this experience becomes close to a state of trance, or to what Myriam Lefkowitz terms a ‘dreaming activity’—a state in which space and time are re-composed through the body, as explored in her performative research Walk, Hands, Eyes (a city). This practice sets the conditions for heightened sensory perception, reshaping how we experience and relate to our surroundings, and in turn transforming the ways images appear, connect, and generate meaning beyond rational construction (Lefkowitz, 2015).

This kind of creative process (characterised by a suspension of time, a cyclical repetition of actions and a multiplication of possibilities in the progression of an un-established narrative) is said to stimulate the right side of the brain, which is the part of our brains more closely connected to our emotions, and thus may serve to access memories that are not rational, neither linguistic nor sequential (Edwards, 1979), and that would be very difficult to access through a more structured exchange such as that of an interview.

In the following section we propose a short itinerary into a selection of these animation processes experienced by Ali, Mohamed and Mahmoud during our collaborative research, to flesh out our reflections on seeing their memories at work.

Animating (and Resisting) Memory through the Specific Technique

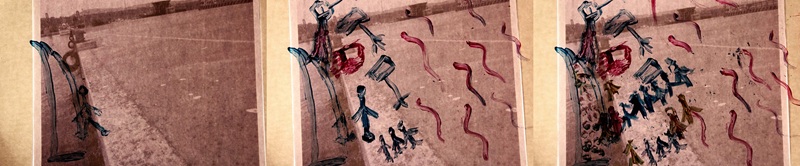

Figure 1.

Mahmoud’s crossing

Figure 1.

Mahmoud’s crossing

Notes. Photograph: Silhouette of Mahmoud on top of a cliff

gazing at the sea, in Lampedusa. Animation: The clear blue sea appears (1). The sun progressively rises on the

horizon. Mahmoud rises his arms and enjoys the beautiful sky. A dark sea

quickly takes over the left part of the image and occupies the entire bottom

part of the frame. Mahmoud is suddenly surrounded by water. Mahmoud’s

silhouette is no more visible. Red spots appear in the water and in the sky.

(Suspension). The colours mix up in dots (made with the fingers) (2). The

outline of two faces with big liquid eyes appears from the abstract pattern.

The silhouette of Mahmoud in the background emerges again from the sea (3).

Finally, the faces melt again and the picture is wiped off.

Source: D’Onofrio (2021).

Mahmoud started from the beach in Lampedusa where he arrived. The first memory that he recalled by looking at the picture was the feeling of peace when watching the sun rising from up a cliff.

The

sea is beautiful when seen from land. It’s not like being in the middle of the

sea, on a small boat with 40 people, where all you can see is the sea. There, the water comes and hits you,

there’s no need to go and touch it. (Mahmoud, personal communication, January

2015, in D’Onofrio, 2017a, p. 125)

Suddenly the water then came and invaded the image, moving the focus to him on the boat in the middle of the sea. At this point Mahmoud stopped and said that he was unable to remember. He then explained that it had taken him so long to forget that moment of his past, that he was now unwilling to remember. Mahmoud’s resistance to remember questioned the role of our facilitation in the memory process, during which we had asked questions such as “What happened there? What part of the story would you like to tell now?”, thinking that they might help to unblock parts of his memory. After a reflective pause, we reassured Mahmoud that the purpose of our work was not to unearth discomforting traumatic memories, and that he had the freedom to twist or conclude the story in any way he preferred (D’Onofrio, 2017a, pp. 126-127).

This was an integral part of our ethical stance throughout the collaboration and the animation process. Emerging entirely from imagination, the drawn animations allowed participants to mask themselves and to weave fiction and metaphor into their stories. Such use of fiction not only offered protection but also opened the possibility of creating something ‘anew’ (Ricœur, 1984). It allowed the story to hold the hesitations present in the act of telling and to follow the shifting trajectories of memory shaped by different experiences—an aspect of memory and narrative creation that is routinely omitted from media portrayals and from the bureaucratic language of suffering, which in contexts like Italy (Giordano, 2015) remains the primary route through which migrants can gain social recognition. In this way, the work moved beyond the often uneasy and ethically questionable pursuit of ‘truth’ grounded solely in factual assertions and a coherent chronological order. This isn’t to say, Paul Ward warns us, that the claims represented are thereby completely invalid:

On

the contrary, it might well be the case that an animated documentary manages to

reveal more of the ‘reality’ of a

situation than any number of live-action documentaries. Animated documentaries

want to engage with the world in all its complexity and contradiction. (2006,

p. 89)

Thus, prompted by the possibilities offered by animation, our conversation with Mahmoud continued as follows:

F: Ok. We can stop here, if you wish. But just one thing: what happens to this drawing when there is no memory? How do we finish this animation? We just stop? We put a black frame? We cancel the drawing?

M: Let me see. Let’s just go on…

Mahmoud then left the brush and used his fingers to blend the colours in the picture, in circular movements. Without saying anything and continuing to mix the colours little by little the outline of two faces started emerging. When we asked him about those faces, Mahmoud replied: “These are my parents, they are crying for their son who’s in the middle of the sea. They have no news, they only know that he took to the sea…” (Mahmoud, January 2015, in It was Tomorrow, 2018).

Even if Mahmoud did not want to remember, the animation process brought him to an unexpected and perhaps even more sensitive realisation: His experience did not belong to his personal memory alone, but it was also inscribed in the feelings and the memory of his family back in Egypt, that he knew had been very worried about him risking his life while crossing the sea. If this animation had been planned with a clear storyboard since the beginning, Mahmoud would have perhaps felt more constrained into a more structured and predictable narration. But in this case, the flow of the improvised storytelling allowed Mahmoud to decide unexpectedly to stop animating and to acknowledge his unwillingness (or impossibility, to use his own term) to dwell into a painful act of remembering. The result was twofold: On one hand he involuntarily transferred and related his unspeakable pain to his parents’ suffering, representing them crying; on the other, the fact of being physically engaged in the process of animating through the stop motion technique enabled another emotional and narrative layer of his story to emerge in powerful expressive and aesthetic ways that would have probably been unimaginable in different circumstances.

The improvised hand drawn animation, therefore, comes very close to the process of creating one’s memory, showing that the act of remembering comes hand-in-hand with that of forgetting. The creative process of animation in fact, may as well help to recover forgotten memories by emplacing the animator’s body in the story and in the place being represented. While painting his experience of crossing and the waves crushing against the boat, Mohamed for example, surprised himself when drawing the drops of water on the passengers and exclaimed: “Ah yes, it was raining! I had forgotten that!”. The progression of the animated narration follows the same process of remembering, like in a tapestry, one detail of story and of memory is sewn up to the next. To use another metaphor, remembering through improvised and hand drawn animation follows the creative process, where a detail remembered and drawn serves as a hook for the next one to be revealed, and only at the end one achieves the full picture.

Animating Emotional Memory

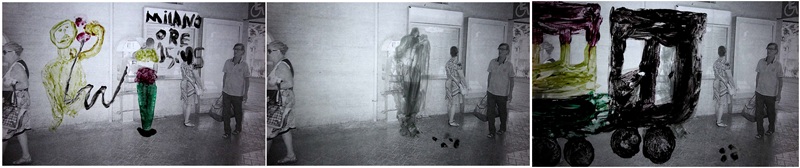

The animation drawn by Mohamed mirrors the sequence of his recollections. He first remembered where the boat docked, then himself stepping onto the pier. As he drew, he recalled imagining he would “land on a desert, where there is nobody, where I can do what I want.” Instead, he was confronted by flashing cameras and police waiting on the dock, realising instantly that “we would end up in the newspapers like criminals” (D’Onofrio, 2018) (Figure 2).

In depicting his arrival, Mohamed identified the precise moment his self-perception shifted: from hopeful newcomer to a highly visible, criminalised subject whose movements in Italy would be restricted by state control. As the animation reached the point of disembarkation, he remembered another intense sensation —the land itself rocking beneath him after 40 hours at sea. To evoke this, he drew waves onto the dock and rocked the entire frame left to right, involving both his own body and the viewer’s perception. After this, he represented the police picking him up and the rest of the passengers progressively disembarking from the boat.

The setting emerged gradually, following the order in which details surfaced in Mohamed’s memory, akin to oral storytelling where a narrator builds the scene piece by piece, leaving the audience to imagine what lies between words and images. By keeping the same frame while shifting from a factual reconstruction to a bodily, subjective experience, Mohamed blurred the line between external description and internal sensation. This shift invited viewers to reconsider the same space through his altered state, with emotional memory shaped not through narration over static images, but through graphic, embodied transformation.

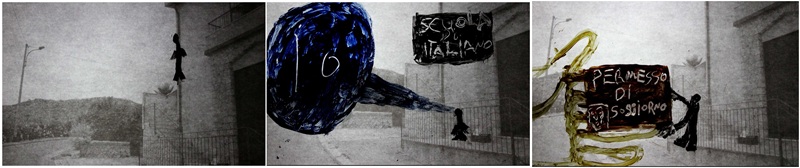

As a medium capable of visualising inner states, animated documentary enables animators to relive and reinterpret their experiences through feeling and imagination rather than mere factual recounting. This recreated nature of animation allowed Mohamed, Ali, and Mahmoud to represent the aspects of their stories they wished to share in ways closer to their nonverbal, emotional, and imaginative experiences. In doing so, they rewrote their memories through desire, fear, and bodily perception. A striking example comes from Mahmoud, who animated his passage through Palermo train station, where — without a ticket and perceiving his presence in Italy as illegal — he felt a powerful urge to be invisible to both authorities and passers-by.

Here, once again, a memory of both feeling and desire is given visual form. Mahmoud’s wish to be invisible — to avoid traffickers, police, and ticket inspectors — is conveyed through the metaphorical disappearance of his body, leaving only footprints on the ground. Like Mohamed in the previous example, Mahmoud uses the imaginative potential of animation to express his internal, emotional perspective. Rather than recounting the event as an oral anecdote, he centres the story on his own figure, representing the wish that arose in response to his perceived exposure to others’ gaze. As viewers, we see how he wanted to be (un)seen, transforming reality through fantasy. As with Mohamed’s first step, material reality is deliberately distorted to give shape to an emotion (Figure 3).

Animating the Imaginative Possibilities of the Past

Beyond its capacity to explore and represent emotional memories, animating directly onto photographs of places from one’s past prompted participants to consider how to convey more vividly what they had felt in those moments. For Ali, working with the unfamiliar medium of hand-drawn animation brought back the peak of his terror while escaping from the port where he had landed after crossing the sea. The moment came when a set of car headlights turned towards him as he was about to run into a dark street. In the studio, he realised that what he imagined in those few seconds best expressed the intensity of that experience.

Uncertain whether it was a police car, Ali’s mind raced through three possible outcomes: being sent back to the ship, repatriated, or imprisoned. His animation shows how imagination actively shapes one’s perception of reality, particularly in the heightened context of entering a country illegally. To express the force of these possibilities, he moved his drawn figure from the street into an imagined “bubble,” running as he had in real life. The animation makes clear that this ‘reality’ of imagination was not abstract but embodied — lived through his nervous system. Here, the representation becomes a branching series of possibilities, like standing at a crossroads and deciding which way to go.

This subjunctive dimension —the “what if…?”— was also central to Mohamed’s later reflection on his escape from the reception centre for minors. After animating the escape itself, he imagined an alternative path in which he stayed, made friends, learned Italian, and received the residence permit available to minors.

Animating such alternative possibilities allowed him to confront the fantasy that had driven his earlier decision — reaching Milan as a symbol of entering the modern world — and to reflect on the doubts that lingered. For Ali, the process revived the car-headlight moment, with its imagined scenarios of how his life could have unfolded differently. Both cases show how, in moments of “crisis” — whether dictated by chance (Ali) or by choice (Mohamed) — imagined alternative lives can take powerful hold of lived reality.

Mahmoud, too, used animation to tell the story of escaping from the reception centre where he had been held. In his case, however, the escape was an unexperienced desire, often discussed with friends at the centre. Through animation, he explored the possibility of rewriting the past, imagining himself staying until his departure was arranged, and in doing so, giving form to a long-held wish (Figure 5).

Across these examples, animation is not simply a means to reconstruct events, but a device for re-living them through emotion, bodily sensation, and imaginative projection. It enabled our research participants to represent not only what happened, but also what was feared, desired, or might have been — producing layered, affective accounts that move beyond a straightforward description of facts.

This blending of reality, dreams, past, and future is central to the open animation process, allowing a narrative to expand from a single memory or event into multiple possibilities. By mentally and graphically exploring different perspectives rather than adhering to one fixed reality, participants re-engage their imagination to envision new personal and collective futures. Drawing and animating dreams and desires, even when anchored in past experiences, can be empowering, offering a clearer sense of direction toward future goals. Ali’s animation imagining his return to the same harbour in the future exemplifies this transformative potential.

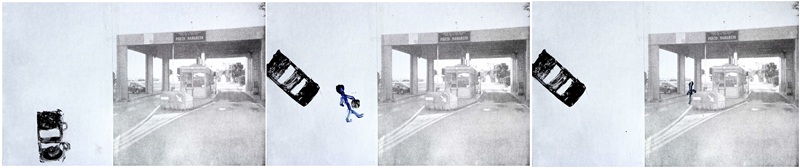

Animation and Memory of the Future

In this animation, Ali returns to the harbour from which he had once escaped. At the time, as an undocumented migrant, he had spotted the main gate, turned in the opposite direction, climbed a fence, and fled into the countryside along a dark road (Figure 4). Years later, visiting the site with Alexandra, he photographed the same gate. Back in the studio, he proposed animating himself walking confidently through it — now as a businessman, free from fear about who he is. Having recently obtained his residence permit after seven years of waiting, Ali could finally enter and exit the port without hiding, and imagine building the life he had envisioned since leaving Egypt (Figure 7).

Through animation, the gate that had once symbolised exclusion became a metaphor for regained possibility. No longer “ashamed to show a copy of my passport, but… proud of showing my identity” (Ali, August 2014, footnote in It Was Tomorrow, 2018), he now imagined himself as a successful trader working with maritime companies. In the animation, this dream becomes real, reweaving past (his escape), present (securing legal status), and future (professional success) into a new autobiographical narrative. The process of reimagining past and future in this way demonstrates animation’s potential as a method for reflecting on personal experience and actively reshaping one’s life story.

Collaborating with people who have experienced migration, animation offers an escape from what’s known as ‘reality syndrome’ (Gallagher, 2007; Thompson, 2009; Jeffers, 2012), common in many migration-related creative projects. While focusing on narrative and testimony can hinder creativity and risk re-traumatizing participants (what we were risking with Mahmoud’s crossing, figure 1), animation provides the freedom to remember, forget, and express through metaphors—enabling a new narrative about the past, future, and self.

The anthropologist Michael Jackson, known for his work on migration and migrants’ storytelling, identifies these narratives as a crucial means for maintaining a sense of agency amidst disempowering situations (2002, p. 15). We can understand therefore how Ali’s animated narrative about his future allowed him to actively reshape past events, shifting from a passive experience to one of personal re-creation.

Conclusion

The animations created by Ali, Mohamed, and Mahmoud offered valuable insight into how imaginative reimagining, rather than sticking to strict facts, can feel more truthful to participants’ memories and experiences. The animation process allowed us to observe how memory is formed through creation and interaction. Memory, thus, emerges as a creative, physical and relational process, while also being a constantly evolving result of that process. Through animation, Ali, Mohamed, and Mahmoud found a narrative medium that allowed them to explore and express different temporal perspectives, sometimes blending or complementing each other, and at other times, presenting contrasts or conflicts.

One of the key aspects of the participatory animated documentary for us was how this hybrid form encouraged the development of collaborative working methods, which are valuable for all anthropological approaches. Ward highlights this as a crucial point, noting that animated documentaries often tackle topics that involve the contradictory and inexpressible thoughts tied to people’s personal experiences and perceptions. This is why such films couldn’t exist without the active participation of those they portray (Ward, 2006, p. 94). It could be said that creating an animated documentary aligns perfectly with the anthropological agenda, as “these films are not just attractions, they are forms of knowledge” (Skoller, 2011, p. 209). During the animation process, we also engaged in a shared learning experience, witnessing how memories and imaginations took surprising shapes, and where knowledge was co-created and negotiated. Thus, experience, memory, imagination, and being are not only ‘emplaced’ (Casey, 1993; Antze & Lambek, 1996; Irving, 2007; Köhn, 2016), but also emerge from specific practices (in this case, animation) that shape the intersubjective exchange between researcher and participants.

The act of making, exploring, and transforming aimed to foster opportunities for mutual discovery rather than simply explaining lived experiences. When collaborating with participants on issues connected to their inner experiences, where imagination, desires, and dreams play a significant role, it is important for us to critically examine our own scholarly representations. We must also create room to question the pursuit of certainties that often underpin anthropological knowledge (Ravetz, 2007, p. 271), as this is part of our responsibility in addressing the complexities and personal challenges shared by our participants. Research should, therefore, begin within experience (acknowledging that we, as researchers, are also part of it), and be done in collaboration with the individuals whose stories we aim to explore. While traditional social research methods may risk solidifying and fixing the transient aspects of people’s lives (Irving & Rapport, 2009) clearing them from hesitation, doubt and ambiguity, the contrast between participants’ artwork and their verbal expressions creates a generative space for social analysis.

Human imagination has the power to contradict reality, creating space for other possibilities to shape our present. In his phenomenological analysis of imagination, Sartre (1940) notes that the defining feature of our imagination is its ability to conceive of what is not the case. This became especially clear during the animation process, where black-and-white photos—lacking colour, action, and emotion—sparked our participants’ memories and imaginations, allowing them to animate and fill in what was absent from the images. For instance, Mohamed explained that the animation of his disembarkation on the pier pulled him back into the scene, helping him relive the events that had taken place there. This illustrates how animation can serve a descriptive function, allowing participants to reconstruct places and moments with visual detail. Yet our work with animation moved beyond description, drawing on its expressive and evocative potential to convey atmosphere, emotion, and imagined possibilities — enabling research participants to create accounts and memories anew. Mahmoud shared that while painting the scenes he was animating, he found it difficult to respond to our reflections or questions:

I didn’t think much, the questions make us think

too much. Instead, I didn’t reply many times, many times I had difficulties in

answering back to you, so I kept on working, and while working the answer to

your question came to my mind. ‘Cause drawing helps

you think all the things you want to do because you can’t give an answer to

everything through words, but you can draw, as we did. (Mahmoud, January 2015,

in D’Onofrio, 2017a, p. 140)

Both Mahmoud and Ali discussed how their memories of being confined in the studio differed from those of walking through the harbours and reception centres. Mahmoud noted, “but with the drawings other things come to mind, it doesn’t have to be something you experienced in that moment. An image comes to your head: I wanted to be like that!” (D’Onofrio, 2017a, p. 140). For instance, the image of his parents crying (Figure 1) and his imagined escape from the reception centre (Figure 6) both emerged through his drawings.

Ali felt that filming the documentary had been the most powerful way to tell certain parts of his story, as it allowed him to be emotionally immersed in the locations tied to his memories. However, when reflecting on the different creative processes, he mentioned that animation gave him the opportunity to explore aspects that the live-action documentary, along with his improvisation, had not been able to express. For example, in his animation of the escape, he explained: “It is in the studio that the memory of the police car came to me as I was thinking ‘how can I render the idea of how I felt in that street, so dark...?” He continued, “I might have forgotten the incident, but then thinking of how to explain how dark that street was, looking at the photograph and drawing upon it, that idea came to me” (D’Onofrio, 2017a, p. 140).

In conclusion, recognizing that the highly mediatic image of the migrant has led to the underrepresentation and “invisibility” of many aspects of migration (Graw & Schielke, 2012), our shared research has aimed to shed further light on the subjective perceptions and experiences of the protagonists by creating a process through which the ethnographic approach and animation converged and could facilitate the complexity of their stories to emerge to a certain degree. Navigating the complex terrain of distorted media discourse, audiovisual, performative, or textual anthropological depictions of migration carry a political duty to bring forth people’s experiences, hopes, contradictions, and voices into the public sphere. In this context, reflective practice—such as that enabled through improvised animation—should be supported as a process that fosters counter-narratives, doubt, and uncertainty. This approach allows practitioners and researchers to resist political and social pressures that increasingly constrain their work (Goodson, 2004, in Bolton, 2010, p. 11).

We argue that any study or creative project addressing such politically charged and visually manipulated subjects must directly challenge the forces that seek to define and limit migrants’ experiences, often speaking for them while denying their agency, voice, and complexity. Collaborative creative practices, like the participatory animated documentary process we employed, offer a means of conducting research alongside our participants, ensuring their voices remain central in challenging the narratives that are constructed about them and their experiences.

References

Antze, P., & Lambek, M. .1996). Tense Past: Cultural Essays in Trauma and Memory, Routldedge.

Berger, J. (2005). On Drawing. Occasional Press.

Bolton, G. .2010). Reflective Practice - Writing & Professional Development. SAGE.

Callus, P. (2012). Reading Animation through the Eyes of Anthropology: A Case Study of Sub-Saharan African Animation. Animation an Interdisciplinary Journal, 7(2), 113-130.

Cangiá, F., & Zittoun, T. (2020). Exploring the Interplay between (Im)Mobility and Imagination. Culture & Psychology, 26(4), 641-653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X19899063

Casey, E. .1993). Getting Back into Place: Toward a New Understanding of the Place-World. University of Indiana Press.

Cox, R., Irving, A., & Wright, C. (2016). Introduction: The Sense of the Senses. In R. Cox, A. Irving, & C. Wright (Eds.), Beyond Text? Critical Practices and Sensory Anthropology (pp. 1-19). Manchester University Press.

D’Onofrio, A. (2017a). Reaching Horizons: Exploring Past, Present and Future: Existential Possibilities of Migration and Movement through Creative Practice [PhD dissertation]. University of Manchester, England.

D’Onofrio, A. (2017b). Reaching for the Horizon: Exploring Existential Possibilities of Migration and Movement within the Past–Present–Future through Participatory Animation. In J. Salazar, S. Pink, A. Irving, & J. Sjöberg (Eds.), Anthropologies and Futures: Researching Emerging and Uncertain Worlds (pp. 189-207). Bloomsbury.

D’Onofrio, A. (2020a). Mohamed’s first step [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/453696490

D’Onofrio, A. (2020b). Ali’s escape route [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/453691292

D’Onofrio, A. (2020c). Mohamed’s escape – the experience and the imagination [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/453694193

D’Onofrio. (Dir.). (2021). Mahmoud’s Crossing – Animation [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/516986355

D’Onofrio, A. (2022). Mahmoud’s Escape – reception of minors [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/779382498

D’Onofrio, A. (2024). The phone call and the Invisible Man [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/951945303

D’Onofrio, A. (2025a). Resonating Identification Photographs: Longing for Possibilities within and Beyond the Border Regime’s Visual Framing. Visual Ethnography, 14(1), 1-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.12835/ve2024.2-172

D’Onofrio, A. (2025b). Ethnographic Animation. In P. Vannini (Ed.), The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video (2nd ed.). Routledge.

D’Onofrio, A. (2025c). Port Ali – a photograph of the future [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/1109303452

D’Onofrio, A. (Dir.). (2018). It Was Tomorrow [Film]. Arts and Humanities Research Council, University of Manchester. Journal of Anthropological Films, 3(2), e2757. https://doi.org/10.15845/jaf.v3i02.2757

Edwards, B. (1979). Drawing on the Right Side of Brain. Penguin Putnam.

Gaibazzi, P. (2012). “God’s Time is the Best”: Religious Imagination and the Wait for Emigration in the Gambia. In K. Graw, & S. Schielke (Eds.), The Global Horizon - Expectations of Migration in Africa and the Middle East (pp. 121-136). Leuven University Press.

Gallagher K. (2007). Dark Dramas: The Occupied Imagination. In K. Gallagher (Ed.), The Theatre of Urban: Youth and Schooling in Dangerous Times (pp. 128-139). The University of Toronto Press.

Gatta, G. (2018). “Half Devil and Half Child”: An Ethnographic Perspective on the Treatment of Migrants on their Arrival in Lampedusa. In G. Proglio, L. Odasso (Eds.),Border Lampedusa (pp. 33-51). Palgrave Macmillan.

Giordano, C. (2015). Lying the Truth: Practices of Confession and Recognition. Current Anthropology,56(15), S211-S220.

Graw, K., & Schielke, S. (2012). Introduction: Reflections on migratory expectations in Africa and beyond. In K. Graw, & S. Schielke (Eds.), The Global Horizon: Expectations of Migration in Africa and the Middle East (pp.7-22). Leuven University Press.

Hamdy, S., & Moll, Y. (2024). Visualizing Erasure: Co‑Creating Comics and Animation from Revolutionary Street Art to Nubian Memories of Displacement in Egypt. Visual Anthropology Review, 40(2), 264–280. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12343

Hogan, S., & Pink, S. (2010). Routes to Interiorities: Art Therapy and Knowing in Anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 23(2), 158-174.

Irving, A. .2007). Ethnography, Art, and Death’. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute (N.S.), 13, 185-208, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4622907

Irving, A., & Rapport, N. (2009, April). Inner Landscapes: Ethnographies of Interior Dialogue, Mood and Imagination [Conference panel]. Anthropological and Archaeological Imaginations: Past, Present and Future, Bristol, UK. https://nomadit.co.uk/conference/asa09/p/551

Jackson, M. (2002). The Politics of Storytelling – Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity. Museum Tusculanum Press.

Jackson, M. .2008). The Shock of the New: On Migrant Imaginaries and Critical Transitions. Ethnos, 73(1), 57-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840801927533

Jackson, M. (2012). Lifeworlds: Essays in Existential Anthropology. University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, M. (2013). The Wherewithal of Life: Ethics, Migration, and the Question of Well-Being. University of California Press.

Jeffers, A. .2012).Refugees, Theatre and Crisis: Performing Global Identities. Palgrave Macmillan.

Khosravi, S. (2018). Stolen Time. Radical Philosophy, 203, 38-41.

Köhn, S. .2016).Mediating Mobility: Visual Anthropology in the Age of Migration. Columbia University Press.

Lefkowitz, M. (2009). Walk, Hands, Eyes (a city) [Performance].

Lefkowitz, M. .2015). Walk, Hands, Eyes (a city). Beaux-Arts de Paris.

Lems, A., & Tošič, J. (2019). Preface: Stuck in Motion? Capturing the Dialectics of Movement and Stasis in an Era of Containment. Suomen Antropologi, 44(2), 3-19. https://doi.org/10.30676/jfas.v44i2.77714

Mahmoud, J. (2015). Interview. Personal archive.

Moore, S. (2018). Does this Look Right? Working Inside the Collaborative Frame. In J. Murray, & N. Ehrlich (Eds.), Life: Issues and Themes in Animated Documentary Cinema (pp. 206-220). Edinburgh University Press. https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9780748694112.003.0013

Morelli, C. (2021). The Right to Change: Co-Producing Ethnographic Animation with Indigenous Youth in Amazonia. Visual Anthropology Review, 37(2), 333-355. https://doi.org/10.1111/var.12246

Nasim, O. W. (2014). Observing by Hand - Sketching the Nebulae in the Nineteenth century. University of Chicago Press.

Pink, S. (2011). Images, Senses and Applications: Engaging Visual Anthropology. Visual Anthropology, 24(5), 437-454. https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.2011.604611

Radley, A., & Taylor, D. (2003). Images of Recovery: A Photo-elicitation Study on the Hospital Ward. Qualitative Health Research, 13(1), 77-99. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302239412

Ravetz, A. (2007). A Weight of Meaninglessness about which there is Nothing Insignificant: Abjection and Knowing in an Art School on a Housing Estate. In M. Harris (Ed.), Ways of Knowing, New Approaches in the Anthropology of Experience and Learning (pp. 226-286). Berghahn.

Ricœur, P. (1984). Time and Narrative. University of Chicago Press.

Sartre, J.-P. (1940). Being and Nothingness (H. E. Barnes, trans.). Routledge.

Schellow, A. (2011). Production Dossier of the Film Tirana. Private email exchange with Francesca Cogni.

Schielke, S. (2008). Boredom and Despair in Rural Egypt. Contemporary Islam, 2(3), 251-270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11562-008-0065-8

Schielke, S. (2015). Egypt in the Future Tense: Hope, Frustration, and Ambivalence Before and After 2011. Indiana University Press.

Silvio, T. (2010). Animation: The New Performance? Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 20(2), 422-438. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43104272

Skoller, J. (2011). Introduction to the Special Issue, Making It (Un)Real: Contemporary Theories and Practices in Documentary Animation. Animation: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 6(3), 207-214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746847711420555

Thompson, J. (2009). Performance Affects: Applied Theatre and the end of the effect. Palgrave Macmillan

Ward, P. .2006). Documentary – the Margins of Reality. Columbia University Press.

Wells, P. (1998). Understanding Animation. Routledge.

Notes

*

Research paper

1

For a more in-depth discussion of the ethnography and its placement within anthropological and scholarly discussions on migration please refer to D’Onofrio (2017a, 2017b, 2025a).

2

Another two notable examples of collaboration between animation and anthropology is the research carried out by Camilla Morelli and Sophie Marsh with indigenous Matse children in the Peruvian Amazon (see Morelli, 2021), and the collaboration between Yasmin Moll and Karson Schenk with Nubian cultural activists in Egypt (Hamdy & Moll, 2024)

3

Authors’

translation of original text in French from an email exchange with Schellow

about his film Tirana (2011): “Le

dessin infuence le souvenir au moment où il est rappelé par la mémoire afin

de s’imprimer sur le dessin : face à la surface du papier, je dépose d’abord

un point, dont la vue stimule ma mémoire ; en réaction, je fais un nouveau

point, qui commence à dessiner une forme liée à ce souvenir - et ainsi de

suite. L’inscription du travail de mémoire qui en résulte peut être lue et

comprise comme une réalisation plutôt qu’une représentation du souvenir.”

Author notes

a Correspondence author.

E-mail: alexandra.donofrio@yahoo.it

Additional information

How to

cite: D’Onofrio, A., & Cogni,

F. (2025). Animating Memories of Migration: A

Participatory Research Collaboration between an Anthropologist and an Animator.

Universitas Humanística, 94. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.uh94.ammp