Introduction

Minority groups are historically excluded, marginalized, and deprived of economic, educational, healthcare, and employment opportunities, limiting their ability to live a dignified life. Moscovici introduced the concept of active minorities, referring to groups that possess characteristics opposite to the majority, and which form elaborated social representations (1,2). In this context, the population of sex workers is part of a minority group that, in addition to facing stigma and exclusion, is organized into collectives and movements that seek to make their demands visible and claim their rights.

In Colombia, there are no exact or up-to-date figures on the population of sex workers due to the clandestinity, social stigma, and lack of official records. A 2019 UNAIDS report estimated around 244,400 individuals in this activity, although the actual number is likely much higher, especially in cities like Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, and Cartagena (3,4). After the pandemic, an increase in virtual sex work was evident, associated with the economic crisis and the search for alternative means of subsistence (5,6). These data reflect the difficulty of measuring a phenomenon marked by clandestinity, which renders sex workers invisible as social and political subjects.

The main reasons explaining sex work in Colombia include economic precariousness, migration—especially of Venezuelan women—the lack of formal employment opportunities, and gender-based violence (7,8). This phenomenon is also observed in other countries: in Mexico, over 232,000 people are reported to be engaged in this activity (9), and in Chile, feminist organizations estimate around 60,000 women, many of them migrants (10). Thus, while sex work is a global phenomenon, its magnitude and characteristics depend on socio-economic, migratory, and cultural dynamics.

It is worth noting that within these "active minorities," there are various populations, including sex workers, the LGBTIQ community, people with disabilities, and others. For these groups, discrimination and lack of opportunities are recurring, which implies an "accumulation of disadvantages" in different contexts, leading to the breakdown of their societal role, as well as a process of stigmatization passed down to new generations in a cyclical manner (11,12).

Sex work has been categorized as a social, professional, and economic activity in which the body is used as a means of production through sexual exchanges mediated by economic agreements, either formal or informal. On one hand, it is recognized as a legitimate practice within the framework of rights and autonomy (13), while on the other hand, it is seen as a form of exploitation that reproduces gender inequalities and power relations (14).

The contemporary debate on sex workers lies at the intersection of feminist, social, political, and human rights perspectives. The abolitionist feminist view considers this activity as a form of violence and exploitation (15), while regulatory movements advocate for its recognition as dignified work with labor guarantees. Cases like ReNaTEP in Argentina or the reforms in Spain (12) illustrate persistent ideological tensions. More than a technical or legal analysis, there is a political use of criminal law, which limits the social understanding of the phenomenon and polarizes it into irreconcilable stances (16). Although some political parties have shown increased interest in including the issue in their platforms, this approach remains fragmented and is related to a largely opposing public opinion regarding its recognition as labor (17).

In countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, sex work has been regulated and allowed to develop; however, studies show that, despite regulation, dynamics of violence and exploitation persist, even in New Zealand, the first country to decriminalize prostitution in 2003 (18). In Sweden, Norway, and France, a model has been adopted that recognizes sex workers as victims and decriminalizes their conduct, while penalizing those who profit from this activity (18).

In countries like Germany, the Netherlands, and New Zealand, sex work has been regulated and allowed to develop; however, studies show that, despite regulation, dynamics of violence and exploitation persist, even in New Zealand, the first country to decriminalize prostitution in 2003 (18). In Sweden, Norway, and France, a model has been adopted that recognizes sex workers as victims and decriminalizes their conduct, while penalizing those who profit from this activity (18).

Since the mid-20th century, international governmental organizations have promoted policies and regional and global dialogues to combat discrimination. In Latin America and the Caribbean, initiatives have been implemented to reduce exclusion and marginality. Among their pillars are social cohesion through the reduction of socio-economic gaps, improved institutional frameworks, and strengthening the sense of belonging (20).

In this process, little attention has been given to recognizing the positive experiences and resources of these populations, which can improve both individual and collective quality of life and, at the same time, foster participatory environments (21). From the perspective of personal and community assets, the so-called general resistance resources (GRR) are defined as elements that allow people to perceive their life as coherent, meaningful, and understandable (22,23). These include material factors such as money, as well as symbolic and social resources like self-esteem, commitment, healthy habits, cultural capital, life vision, social support, intelligence, and tradition. Their availability, or the possibility of accessing them in the immediate environment, increases opportunities to face adversity and build stronger coping strategies against exclusion (21).

Rivera de Ramones (24) suggests that the aim is to promote a pleasant life, adequate and positive functioning, as well as the ability to overcome obstacles. This perspective links emotions (laughter, sadness, joy, despair, fear, or satisfaction) with places and environments (home, street, park, neighborhood, or restaurant). Thus, it is understood how individuals, through their bodies organized by gender and work, inhabit space, appropriate territory, walk freely, and participate in governance and social planning processes (25,26).

Identifying assets in vulnerable populations can be done through mapping (27) to recognize intangible skills and strengthen community development. This enables a joint construction with the population and transforms the geo-spatial-emotional environment. Brunn (25) emphasizes the importance of mapping to understand emotions in relation to specific locations and to understand not only where things are, but where they could or should be. The link between territory and emotions is crucial for improving the understanding of human groups.

Various studies have analyzed vulnerability situations through mappings that include collective participation (28). For example, mapping exercises have identified geospatial data on access to limited resources and highlighted the lack of economic and social opportunities, as well as marginalization and criminalization in urban settings (29,30). Furthermore, various studies on sex workers have used cartographies to make their experiences, strategies, and the spaces they inhabit visible. In Chile, studies on self-managed work in Santiago and Concepción have shown how these initiatives promote horizontality, rotation of labor, collective ownership, and links to social and political life, challenging traditional labor norms (31).

In Brazil, the accounts of the sex workers themselves have helped understand the construction of subjectivities and the articulation between body, desire, and stigma, highlighting how their narrative contributes to the history and understanding of prostitution (32). Other studies on urban sexual cartographies and power relations have pointed out that sex workers design negotiation strategies, client selection, and empowerment against work risks, showing they have more agency than is typically socially recognized (33).

Research in Mexico on sexual harassment in public spaces and in Argentina on the migratory movements of transfeminine individuals has shown how the use of space and geographical displacement condition risks, opportunities, and life projects (34). Finally, studies on social imaginaries have emphasized that the perception of the body influences the construction of gender identity and how sex workers perceive themselves, reflecting the multiple dimensions of their experience and subjectivity (35,36).

Based on reflections on their specific realities and needs, this study aimed to analyze the personal and community assets of the sex worker population in Manizales (department of Caldas, Colombia).

Method

Study Type

This was a qualitative study grounded in a thematic content analysis from a sociocritical perspective (37). Priority was given to the participants’ daily lives and experiences, establishing a dialogue between the women’s subjectivity and their territory. A social mapping approach was conducted, using a language that represented the geographical space and considered reality from individual, collective, and political dimensions, based on the space as perceived, conceived, and lived by the population (28).

Context

The research was conducted in Manizales, in an area characterized by conditions of vulnerability, by an interdisciplinary team trained in public health, nursing, and gender studies, with experience in community research and work with women in situations of vulnerability and forced displacement. The process was designed as a shared construction using social mapping as a relational strategy, allowing conventions and territories to emerge through dialogue with participants. The team maintained a continuous reflective practice to ensure that the voices of the participating population guided the interpretation and collective hermeneutic practice, considering their experiences and knowledge in the analysis.

The 26 participants were selected using the snowball sampling method (38), a technique suitable for hard-to-reach populations such as sex workers in Manizales during 2021 and 2022, due to stigma, clandestinity, and the lack of official records. This strategy allowed the identification of initial participants through community references, who in turn facilitated contact with new members.

Data collection and analysis were conducted concurrently. Each workshop and social mapping exercise immediately fed into the coding process, allowing the adjustment of questions and the deepening of emerging categories in subsequent sessions.

Techniques and Instruments

To identify personal and community assets, digital mapping using technological tools such as Google Maps and MapHub was combined with social mappings led by the study population, which recognized available resources, social dynamics, aspirations, projections, ideas, goals, potentials, and limitations inherent in their environment. Both methods were integrated and complemented within the framework of social mapping (39). Group meetings and workshops were held, supported by informal dialogues and unstructured interviews.

During mapping, meanings, emotions, and experiences were identified using a color-coding system based on questions, with responses associated with colors via mnemonic cards: green for positive and rewarding aspects, orange for neutral positions, and red for tension, representing low scores in participants’ experiences.

For the mapping, brief response options used in social mapping were defined. For example, the item “community leaders” referred to women recognized in their immediate environment for their organizational and supportive capacity; the item “support networks” included family, neighborhood, and associative links that provide emotional or material support; and the item “work sectors” referred to the usual spaces where participants engage in economic activities.

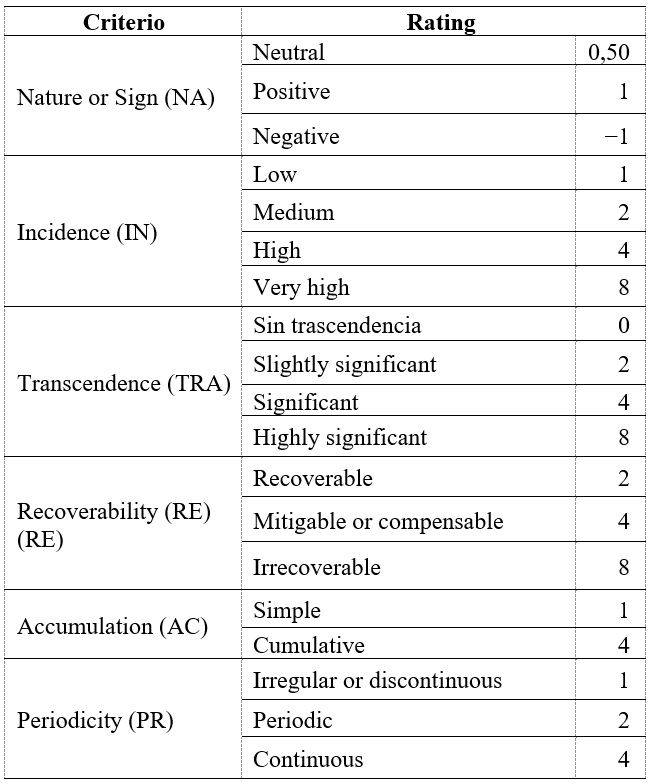

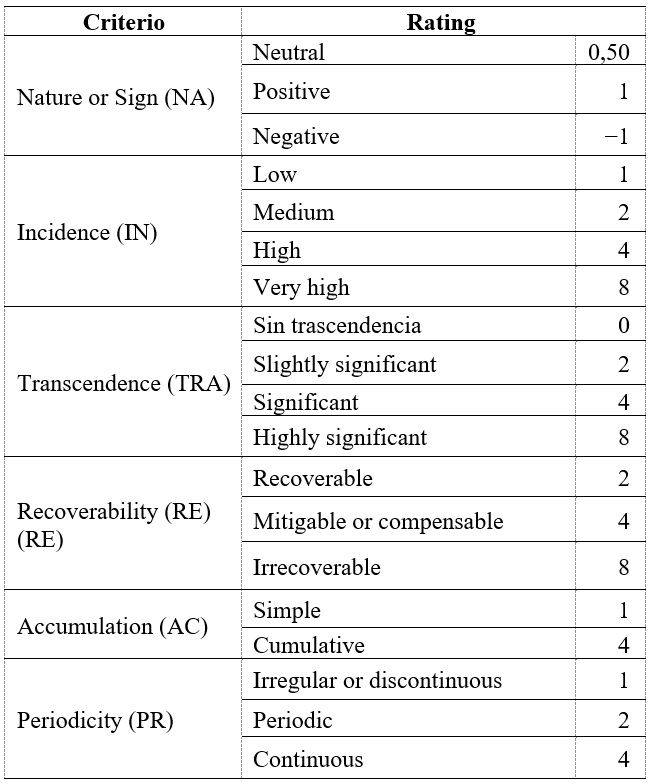

The conventions used correspond to coded representations of the personal and community assets (physical, social, cultural, and emotional) identified in participants’ daily lives. These were rated according to an adaptation of the Conesa-Fernández method, using six criteria: Nature (NA), referring to beneficial character; Incidence (IN), understood as the intensity of the convention; Transcendence (TRA), estimating the area of symbolic influence; Recoverability (RE), indicating the possibility of total or partial reconstruction; Accumulation (AC), as the progressive increase in the manifestation of the effect; and Periodicity (PR), assumed as the regularity of effect manifestation (40). The data obtained from the mappings were systematized in an Excel matrix (Table 1).

Table 1.

Assessment of Factors

An adapted algorithm was used to numerically rate an aspect as negative, positive, or neutral in each convention:

I (I−VALUE) = (IN) + (TRA) + (RE) + (AC) + (PR) × NA

Data analysis was guided by the principles of theoretical sampling, insofar as the emerging categories directed the incorporation and saturation of information. The analysis was performed using ATLAS.ti software, version 9. For data coding, 17 emerging categories and 30 subcategories were employed, which arose from the themes and patterns identified.

Declaration of Ethical Aspects

This study complied with the parameters established by the Declaration of Helsinki (41) and Resolution 8430 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia (42). Approval was obtained from the Bioethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Universidad de Caldas (CBCS-044). In addition, participation was voluntary, and participants signed an informed consent form through which all relevant information about the study was provided. The dissemination of results was carried out through a feedback session with the participating sex workers and the territorial entities involved in the process (the Manizales Secretariat for Women and the Mayor’s Office of Manizales). This action fostered inter-institutional dialogue to guide the development of contextualized public policies.

Results

The territory was explored as a vital medium for understanding the cultural, economic, emotional-symbolic, and political frameworks of the region, in addition to highlighting its role in the manifestation of the lived experiences of its inhabitants within a specific temporal context and in the comprehension of prevailing social dynamics. The recognition of assets was achieved through mapping exercises, which facilitated a general characterization, the identification of geo-emotions, and the exposure factors faced by this specific population.

General Characterization

Among the participants, 18 identified as cisgender and 8 as transgender. Ages ranged from 20 to 54 years, with a mean age of 21.50 years and a median of 20 years. Regarding educational level, 3.8% (one participant) had completed primary education, while 19.2% had not. 65.4% had completed secondary education, 3.8% (one participant) had not finished it, and 7.7% had technical or technological training. 61.5% were single, and 34.6% reported living in a consensual union.

In terms of biological sex, 69.2% identified as female and 30.7% as male. Regarding gender diversity, 69.2% identified as cisgender women, and 30.8% as transgender women. 15.4% of participants reported being victims of the armed conflict, and an equal percentage identified as community leaders.

With respect to health insurance coverage, 76.9% were enrolled in the subsidized health insurance plan, while 11.5% lacked information about their enrollment. 7.7% were affiliated with the contributory health insurance plan, and 3.8% (one participant) belonged to the uninsured low-income population. Additionally, 11.5% were identified as displaced persons, 84.6% reported no special condition, and 3.8% (one participant) identified as migrant population.

It is noteworthy that children play a fundamental role in these women’s pursuit of opportunities. 26.9% of participants had no children; among those who did, 50% reported having between one and three children, and the remaining 50% reported having more than four. Some participants reported a particularly high number of children—one of them had 14.

Meaningful Territorial Co-construction Through Body and Community Mapping

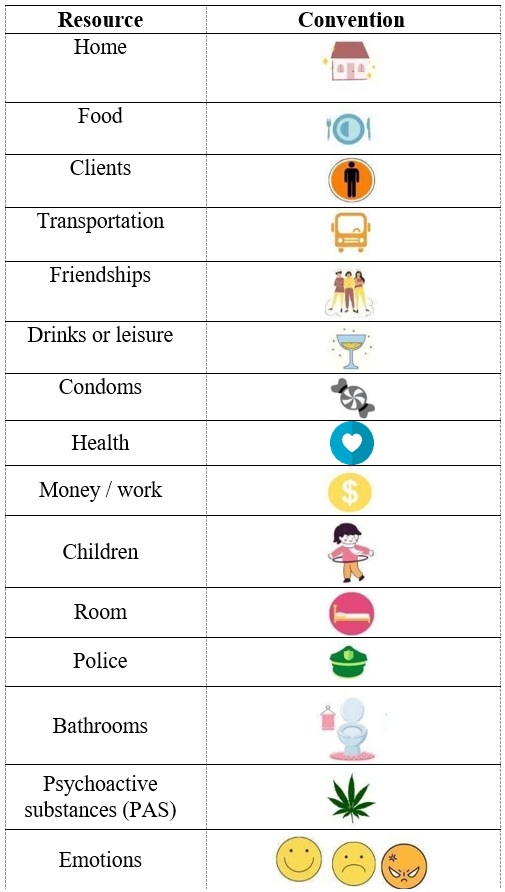

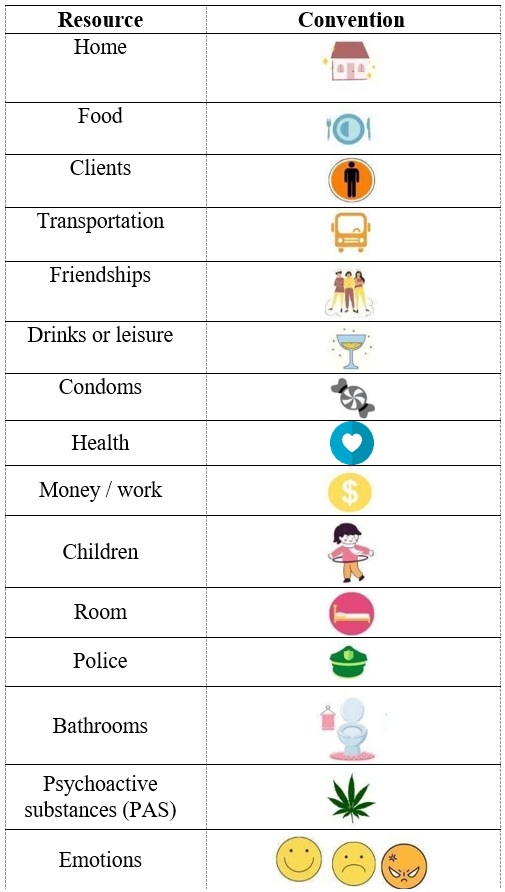

A total of 15 factors were georeferenced, identified as physical, economic, cultural, and social assets—both personal and community-based—across the various territories that women navigate in their daily lives. These factors are represented through mapping conventions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conventions for

Physical, Economic, Cultural, and Social Resources

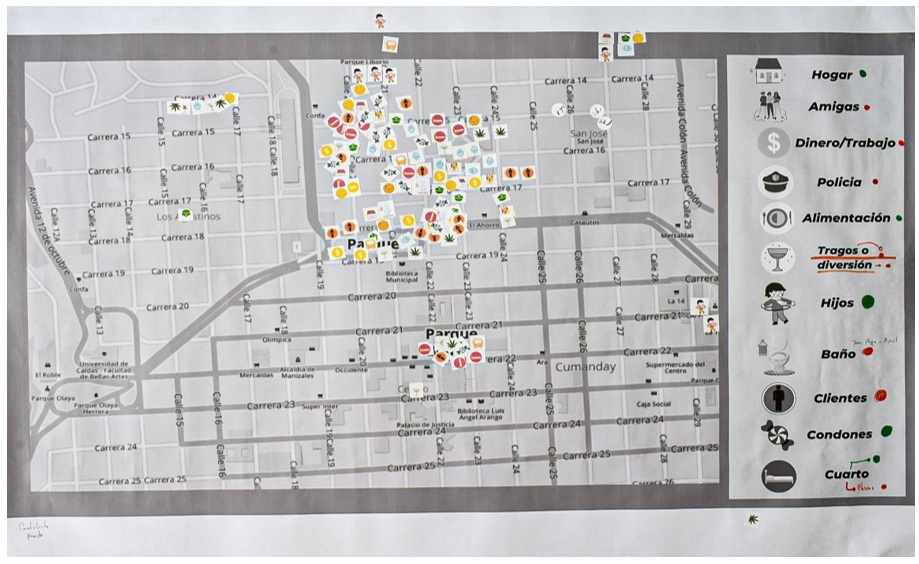

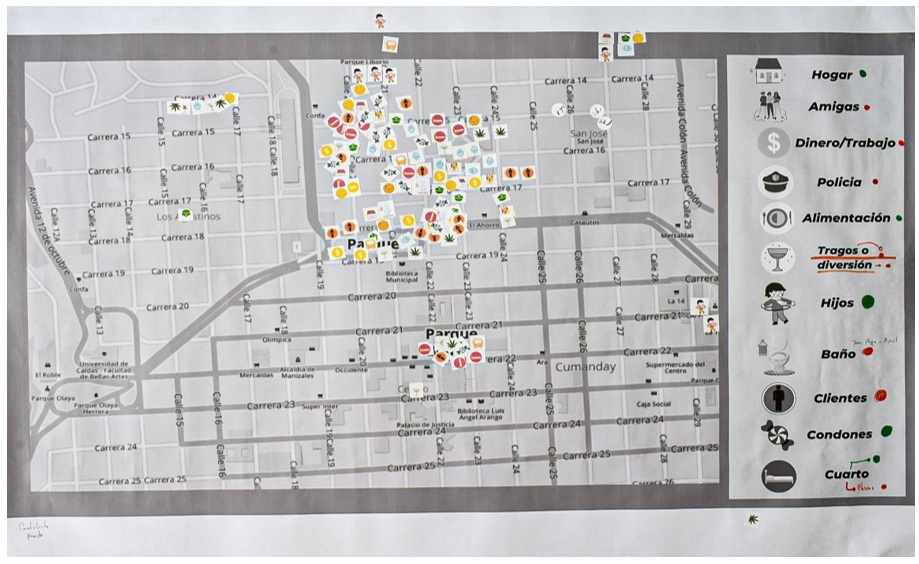

The mapping exercise developed with the women illustrates how they used different spaces for various aspects of their daily lives. The distribution of the conventions revealed areas designated for work, socialization, basic needs, and safety. This spatial arrangement suggested a territorial division that reflects both social and professional organization (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Community Mapping

Developed by Sex Workers

Figure 1.

Community Mapping

Developed by Sex Workers

* Urban map showing

symbolic representation of social and spatial relationships (original in

Spanish). Translation of conventions: “Hogar” = Home; “Amigas” = Friends;

“Dinero/Trabajo” = Money/Work; “Policía” = Police; “Alimentación” = Food; “Tragos/diversión”

= Drinks/Fun; “Hijos” = Children; “Baño” = Bathroom; “Clientes”

= Clients; “Condones” = Condoms; “Cuarto” = Room.

The conventions of “Friendships” and “Children” were widely distributed, reflecting that social connections and family bonds are fundamental in the lives of sex workers and transcend the boundaries of a single space. Likewise, the “Children” convention highlighted areas that the workers perceive as safe for their families, often in proximity to other conventions such as home, police presence, and food. The dispersion of these conventions demonstrated the need to move through a variety of urban spaces, underscoring mobility and access as essential elements for maintaining social and support networks.

The mapping also reflected working conditions and well-being through the “emotions” convention. These expressions were linked to social and economic dynamics, exposure to danger, and accessibility to essential resources. Happy faces pointed to places of positive experiences for the workers—spaces likely associated with safety, community support, or easy access to resources. In contrast, sad faces indicated challenging areas, such as isolation, problematic interactions with clients, lack of support, or difficult working environments. Finally, angry faces marked zones of tension, corresponding to conflict scenarios such as altercations with the police, violence, difficult clients, or aggressive competition among workers.

These mapping exercises provided an intimate insight into the lives of sex workers. Additionally, the visual representation of their bodies was used as a canvas to express their dreams and fears. The illustrated dreams revealed aspirations toward a better quality of life, evidenced by the desire for economic stability, a safe home, and the well-being of their children. These hopes extend beyond their current circumstances, showing a constant pursuit of safety and stability. Among their dreams were owning a house—even in informal settlements—, undergoing plastic surgery, and having a job that provides economic security. Many also dream of starting small businesses, such as jewelry sales or hairdressing, or continuing with training workshops they are already attending. Some expressed satisfaction with their current work, stating they would not change it; however, others aspire to alternative life projects, such as completing high school or taking crafts, dressmaking, or entrepreneurship courses to open new employment opportunities. The lack of financial resources remains a significant barrier, as losing work hours would affect their ability to feed their children.

Their aspirations intertwine with fears, drawn on their bodies as tangible reminders of the realities they face daily. Violence, disease, and insecurity are palpable fears represented in body areas that may have experienced trauma or symbolize vulnerability. Moreover, their concern for the safety and future of their children reveals the depth of their maternal role and their struggle against adversity to provide them with a better life.

They also represented themselves through virtues and flaws. Virtues such as friendship and the ability to care for others underscore the importance of human connection and community support in their lives. On the other hand, openly acknowledging their flaws reflects a degree of introspection and self-awareness that challenges the stereotypes and one-dimensional narratives often imposed upon them.

The use of colors and symbols in the maps not only added an aesthetic dimension but also encoded emotions and priorities. Bright colors and symbols of houses and hearts represented their hopes and passions, while darker tones and somber imagery illustrated their fears. These visual elements functioned as a shared language narrating stories of struggle, resilience, and hope.

These participatory mapping tools revealed a comprehensive perspective of physical territories intertwined with the body. In this sense, the adopted approach highlights crucial assets and underscores the need to address their specific concerns and challenges from an empathetic, woman-centered perspective.

Recognition of Geo-emotions: Protective and Territorial Exposure Factors

The community and personal assets of sex workers—such as their homes and relationships with their children, social interactions with friends, forms of entertainment, work dynamics, and interactions with clients—together with the influence of external factors such as police presence, health services, and access to basic facilities (e.g., bathrooms), provide a detailed view of the complexities of their daily experiences.

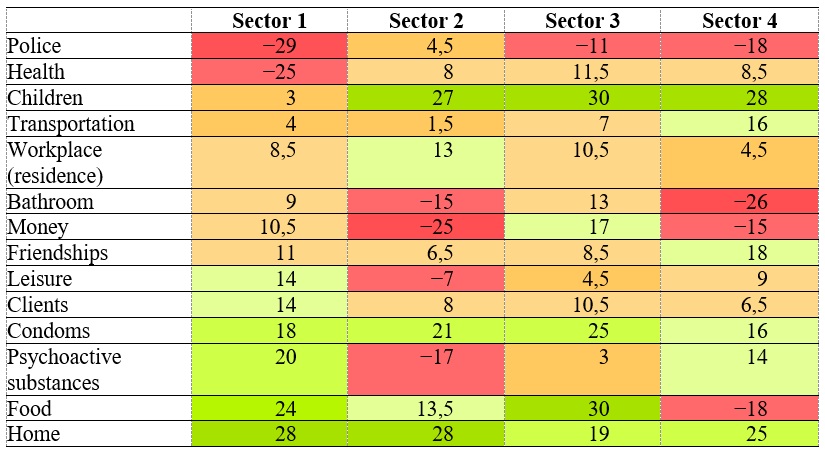

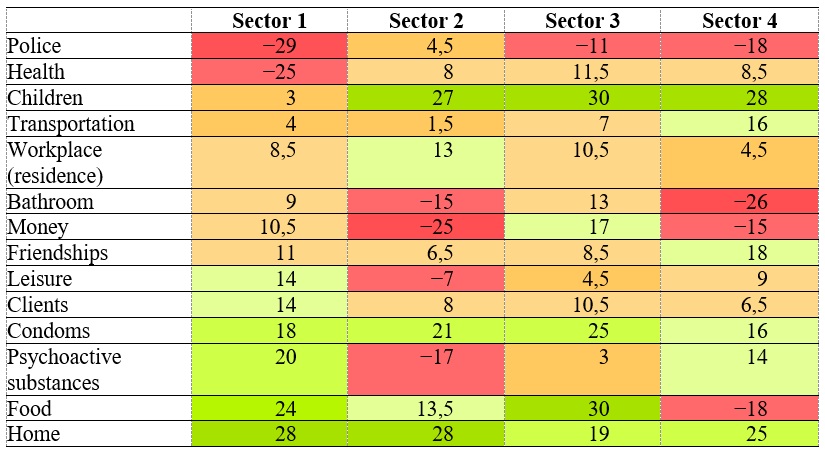

These assets, represented through the mapped conventions, were evaluated by four groups representing different work sectors, understood as the places where they carry out their activities: streets, residences, bars, and others (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of

Conventions by Work Sectors

The home is a crucial asset and exerts a significant influence across all groups. It serves as the refuge where most women feel comfortable and safe with their children. However, certain dysfunctional relationships with cohabitants or the fear of loneliness, in extreme cases, can lead to suicidal thoughts. In the body mappings, this fear was graphically expressed in the chest and head, areas where participants located “the pain of being alone” or “the pressure of economic problems” (3:15). One participant stated: “Because we trans women constantly need psychological help… No one knows what it’s like to be standing on a corner freezing and completely exposed… I think we should always be getting psychological support.” (3:30) These expressions demonstrate that the body was used as a medium to represent feelings of vulnerability and emotional exhaustion, where loneliness, exposure to the elements, and experiences of social rejection materialized in representations linked to suicidal ideation.

For cisgender women across all sectors, their children are their top priority—a source of motivation, inspiration, and happiness. In contrast, transgender women did not attribute the same level of importance to children, even when referring to nieces or nephews. It is notable how participants emphasized care, avoiding taking their children to places such as parks where drug use was visible, and instead choosing healthier recreational spaces: “We don’t like taking them to places like parks where there’s drug use because we don’t want our children there. We prefer taking them downtown, to Chipre, so they can play.” (2:15)

Regarding the use of psychoactive substances (PAS), no direct link was found between drug use and sex work. Participants mentioned social alcohol consumption as a leisure activity and noted the presence of drug use in neighborhoods, especially in parks, which influenced their choice of spaces for spending time with their children.

Friendships were perceived in diverse ways: some viewed them as positive factors, while others saw them negatively, as mere work companions. In the body maps, friendships were drawn on the arms and hands, associated with support, but also with the vulnerability of “trusting and being betrayed” (7:9). A greater sense of community orientation was evident, marked by unity, joy, and trust, revealing strong bonds of friendship.

Leisure was also perceived diversely. Social drinking was considered positive by some, as it was associated with relaxation and strengthening friendships. For others, it was neutral, as they expressed being unable to enjoy leisure due to lack of resources. Those who saw social drinking positively regarded it as a way to relieve stress. In contrast, others felt frustrated, explaining that they only went from home to work, lacking money or time to go out, feeling trapped by debt and the constant need to provide food. These limitations were depicted in the body mapping as a burden on the body, associated with debt and hunger. One participant explained: “To be able to study… if I’m a sex worker and go to school, then I won’t have money to eat or pay rent.” (3:33)

Participants expressed diverse opinions about clients, which varied by age. Women under 25 reported greater desire and acceptance from clients. In contrast, older women described an evolution in client relationships—some clients became benefactors, providing financial help and respectful treatment, although situations of aggression and vulnerability persisted.

Condoms were regarded as a crucial resource by all groups—essential for protection and easily accessible in residences. However, some mentioned that they earned more money when not using them.

In general, residences were positively rated, described as clean and comfortable according to participants’ health and safety criteria. Nonetheless, some lacked proper hygiene or adequate bathrooms. Moreover, participants mentioned the dual role of administrators: some protected women from problematic clients, while others failed to defend them or even sided with aggressors on certain occasions:

There are already

specific places where we go to work, but in some of them we don’t feel as

protected as we should, because the people who manage those places are mostly

women. They don’t defend us from the clients, and sometimes they even side with

the men. But in other places, they do protect us from clients who cause

trouble. (2:23)

Regarding the police, the participants perceive their presence and actions as an exposure factor that places them in a situation of vulnerability, which they rated negatively. Trans women were those who most frequently reported aggressions by this institution. In general, they criticized the mistreatment and abuse of power, noting that officers act arbitrarily, even without justified reasons:

In the areas where the police are present, they mention that they don’t trust them, saying, “they search us for everything.” They all rated them as orange and red, and they report being taken to jail for defending themselves against homeless people. (1:15). “There is a lot of repression… from the police against trans women, because we are being violated." (3:44)

The women rated access to health care negatively due to the obstacles they face in obtaining and continuing medical and legal processes necessary to reaffirm their gender identity, as well as in accessing hormones and surgical procedures. Although some acknowledged being able to use health services, several factors prevented them from doing so — including disrespectful treatment from health personnel, lack of training in trans care, high costs of certain procedures, long waiting times, and complex administrative processes. In the body mappings, health difficulties were associated with discomfort in the heart and abdomen, where participants marked pain or illness. One participant recounted: “I had surgery a month and a half ago... On my ID card it says female... A woman came and said: ‘Hey, sir, I came to give you the medication’... I think that’s really disrespectful.” (3:15)

The bathroom, as an essential space in their daily lives, was identified as a critical exposure factor. They do not have access to adequate or free sanitary facilities; in restaurants and cafés they must pay to use them, which reduces their income. Moreover, many of the rooms they rent lack bathrooms, so they avoid drinking liquids to reduce the need to urinate: “When working on the street, there are no public restrooms available to use, so it’s very hard to find one.” (2:18) Cold days become a disadvantage for them, as the need to use such facilities increases.

In relation to economic and financial resources, the women reported a decrease in income, as clients no longer pay as they used to, and on some days they earn nothing at all. Food is one of the most critical factors; most reported that they generally eat only one meal per day. When working on the streets, they often lack money to buy food, highlighting that those who are organized in groups eat better.

Transportation also emerged as a key factor, especially for women who do not live in the work area and must travel from other parts of the city, which reduces their earnings and limits their ability to meet basic needs.

An emerging category was territorial dispute. Sex workers have specific areas where they avoid working to prevent conflicts with others. They generally do not mix across territories to maintain coexistence. Venezuelan women are not accepted in certain sectors because they offer services at lower prices, which reduces job opportunities for others. This control is expressed through the capacity to decide who may enter the community and the allocation of work spaces: “I’d mention L., from here in Plaza Bolívar, because the girls listen to her. When there’s a problem between them—and there often are—she’s the one who settles things.” (3:23)

The evaluation of these assets across different sectors revealed not only the diversity of their experiences but also the nuances in their discourses. While some highlighted the importance of children and friendships as sources of support and motivation, others emphasized loneliness and the lack of trustworthy networks.

Similarly, their views on clients were mixed: for some, clients represented a source of income and occasional support; for others, they signified risk and abuse. In their accounts about police and health services, narratives consistently described experiences of discrimination and disrespect, particularly among trans women.

This variety of discourses made it possible to identify common points of vulnerability—such as precarious working conditions, insecurity, and stigmatization—alongside expressions of agency and resilience, reflected in their desire to improve living conditions and secure a more stable future.

Discussion

The results of this study highlight how the stigma, prejudice, and stereotypes surrounding sex workers shape psychosocial and political imaginaries that directly impact their affective-behavioral dimension (43). This creates an environment of vulnerability. In this sense, stigma forms the foundation of violence against these populations (44). Studies such as that of Álvarez et al. (45) emphasize that asset mapping makes it possible to highlight and enhance the capabilities, tools, and resources available to communities; this allows for transcending stigma toward a knowledge construction based on being and acting. In this way, the capacity to respond in situations of vulnerability is fostered, from the role of active subjects (27).

A relevant finding is how family and children emerge as the primary asset for these women, as they constitute the central axis of their daily lives and their main source of motivation. The need to generate quick income to support their households emerges as the main reason for their work, a finding consistent with Schwartz et al. (46). It is also observed that many of them live with their children and partners, and maintain close relationships with other family members such as parents or siblings, which strengthens their support network (47). In contrast, the study by Evens et al. (48) reveals that sex work can also lead to family disputes and tensions, forcing workers to engage in their activities clandestinely, without the knowledge or support of their families.

Clients, on the other hand, represent an intermediate asset, as they are the direct source of income. While few conflicts arise from their interactions, these tend to emerge when excesses or unagreed behaviors occur during the service (49). In urban contexts marked by social inequality, such conflicts with clients more frequently escalate into violent situations (50). Some clients are seen as benefactors, which aligns with previous studies on the relational dynamics between both parties (51). However, most maintain a strictly commercial relationship. As López-Riopedre (49) notes, the transgression of these boundaries generates more complex codes and parameters, which lead to conflicts. In critical moments, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this population faced heightened vulnerability, with clients exploiting the adverse economic context to impose lower prices and engage in higher-risk practices (52).

This study identified police harassment, particularly toward trans people, as a central exposure factor. This aligns with findings from previous research, which highlight the stigma and violence exerted by institutional entities against this sex-working population in Latin America and Europe (53). The National Report on Institutional Violence against Sex Workers in Colombi. documents that detentions, often without cause, are frequently accompanied by verbal and sexual assaults perpetrated by police forces and judicial agents (54). This scenario reflects an abuse of institutional power, a situation also reported by Dasgupta and Sinha (55) in the context of India.

Territories are configured as a fundamental asset in the lives of sex workers. The appropriation of public spaces, driven both by necessity and social exclusion, contributes to the construction of a collective identity (56). The need for safe environments — access to bathrooms and risk reduction in negotiations — underscores the tension between client interests and the well-being of the sex-working population (57-59). Furthermore, the persistence of a homogeneous view of this population makes it difficult to provide adequate support, distorts their reality, and affects their credibility with institutions (52).

In alignment with the participatory approach of the study, the findings were shared in a collective event with the active participation of both the study population and decision-makers. This space allowed for the presentation and discussion of the results in an accessible manner, the collection of observations, and the contrast of interpretations from the research team. The feedback not only validated the relevance of the results but also facilitated ownership by the participants, giving credibility to the analysis and ensuring that the conclusions faithfully reflected their voices and realities.

Conclusions

This research demonstrated that social connections and family bonds are fundamental in the lives of sex workers and define the spaces for their daily activities within the territories they inhabit. The identification of emotions related to working conditions and well-being made it possible to define safe environments and community support areas, as well as zones of challenges, problematic work environments, and tension. It is evident that territory is not a neutral space, but rather one marked by inequalities and experiences of violence, highlighting the urgency to improve community safety and local labor infrastructure.

Through the reflection of sex workers on their embodiment, both fears and difficulties were visualized, but also hopes and visions of alternative life projects that enhance the fight, resistance, and hope for a better future. It was evident that sex workers possess agency and the capacity for community organization, key elements to advance towards processes of empowerment and social recognition. However, structural barriers such as stigma, institutional violence, economic precariousness, and the lack of access to basic services continue to limit their ability to improve their quality of life.

Family, children, friendships, and home were identified as the most significant personal and community assets for the sex-working population. These elements enhance resilience and are important for motivation, support, and the construction of a sense of life. Other factors, such as the streets, residences, and interaction with the police, represent exposure scenarios that increase vulnerability. The relationship with clients constitutes an ambivalent asset: on one hand, it is an essential source of income and, in some cases, economic support; on the other, it involves risks related to violence, exploitation, and unprotected sexual practices. This underscores the need to strengthen self-care strategies and workplace safety.

The documentation and analysis of these realities, through cartographic techniques, contribute to the understanding and claiming of these spaces, as they lay the groundwork for dialogue, socialization, and the formulation of public policies aimed at structural changes. In this regard, future participatory processes can strengthen the social fabric and enhance community assets, promoting the coordination of various stakeholders and sectors in favor of the most vulnerable populations.