Introduction

Contemporary medical education in Mexico can be understood as a historical process of epistemic construction marked by tensions between traditional knowledge systems, technical rationalities, and multicultural horizons. Although it incorporates local interpretations and intercultural perspectives, it remains anchored in a positivist paradigm of a biologicist nature, institutionally and socially legitimized as “scientific.” This paradigm reproduces a hegemonic educational logic situated between an artisanal-type training and the uncritical adoption of modern biomedical technologies. This duality sustains a pedagogical model that prioritizes technical skill over ethical dimensions, protocol repetition over critical reflection, and hierarchical obedience over professional autonomy. Such dynamics have profound implications for the quality of care provided, the dignity of medical trainees, and the full exercise of their human rights within teaching and healthcare settings (1,2).

The undergraduate medical internship constitutes a terminal phase of the training process, during which the student transitions from theoretical learning to supervised clinical practice. This period, conceived as a space for applying knowledge acquired during preclinical training, seeks the refinement of skills, competencies, and clinical judgment—elements essential for professional practice. However, this stage does not unfold in a pedagogical vacuum; it takes place in complex hospital environments where healthcare logics, institutional demands, and hierarchical structures converge, placing strain on its formative nature. Under these conditions, the internship is configured as a hybrid space between the educational and the operational, in which educational quality, personal safety, and respect for human rights depend on the effective shared responsibility between training institutions and healthcare services. Nevertheless, this shared responsibility is fragmented by structural omissions, organizational deficiencies, and normalized practices that systematically undermine the professional dignity of medical trainees (3,4).

Various studies have documented the tensions between the educational expectations and the realities experienced during the undergraduate medical internship in Mexico. In particular, a qualitative study showed that although students enter this stage with enthusiasm and a sense of achievement, feelings of uncertainty, overload, and vulnerability quickly emerge. While some testimonies express satisfaction with reaching this stage, most describe experiences marked by systematic mistreatment by attending physicians and residents; long work hours that limit time available for study, meals, or rest; and structural deficiencies in the academic program. These findings shape a persistent pattern of conditions that compromise not only the quality of training, but also the full exercise of fundamental rights, including access to health, education, and decent work (5).

Recent empirical results in Mexico confirm the complexity and severity of the conditions endured by students during the undergraduate medical internship. Notably, an alarming prevalence of sexual harassment has been documented, reaching 83% in the general student population and up to 89% among women, evidencing a structural issue that far exceeds anecdotal accounts (6). Although some studies suggest that the existence of support networks may mitigate the immediate academic impact, such a superficial reading overlooks the psychosocial, ethical, and professional consequences derived from the normalization of violence in training environments.

However, the problem is not limited to the direct harm experienced by interns. The lack of academic planning, institutional indifference toward educational quality, and the absence of adequate physical and instrumental conditions for clinical learning configure a scenario of training precarization that has become a normalized tradition within the Mexican medical internship (7). These conditions reveal a structural crisis that affects the pedagogical meaning of the internship, transforms it into a space of operational subordination, and undermines the full exercise of fundamental rights.

This article was developed with the purpose of constructing a complementary and integrative perspective capable of triangulating two paradigms—the empirical and the interpretive—in dialogue regarding the conditions that either support or undermine the exercise of the right to medical education in Mexico. Specifically, the objective was to analyze and interpret findings derived from the training process of students during the internship year in the state of Veracruz, with the aim of strengthening critical evidence and proposing effective intervention measures.

This problematic context requires an approach that goes beyond merely describing adverse conditions, and instead examines them from a structural, ethical, and epistemic standpoint. In this sense, the study is framed within an interpretive evaluation logic using methodological triangulation, aimed at making visible the normalized practices of institutional violence, identifying areas for educational improvement, and contributing to the transformation of the medical education model toward more just, dignified, and emancipatory frameworks.

Method

The information used in this study is the result of ongoing observations conducted since 2017 at the Medical Education and Human Rights Observatory (OBEME) at a public university in Mexico, focusing on undergraduate students in hospital settings (interns). Specifically, it was part of a project aimed at understanding the experiences and perspectives of the research subjects. To achieve this, an interpretive-critical qualitative study with methodological triangulation and thematic content analysis was developed, oriented towards the structural evaluation of rights in medical training. The phases of this study are described below (8-10).

As a criterion for consolidating and validating reliability, a mixed-method triangulation procedure was employed, characterized by: a) an integration of quantitative and qualitative methods, using preliminary statistical measurements (Phase 1) along with content analysis of open-ended responses (Phase 2 onward); b) a structured analytical sequence following progressive phases (familiarization, coding, categorization, and interpretation), which allowed for cross-validation between numerical and narrative data; c) theoretical cohesion criteria for the dimensions of the construct (safety, education, and decent work), which served as interpretive axes guiding the coding and categorization; and d) the use of empirical and theoretical backgrounds as a framework to articulate structures, processes, and outcomes, thus reinforcing the dialectical and critical approach (11).

In Phase 1, preliminary quantitative measurements from two concurrent studies were employed. These studies focus on this population of students and examine the right to medical education during the undergraduate internship in Mexico, as well as the evaluation of acts of violence during this formative period. This constituted the first phase of data collection necessary for the triangulation process. Subsequently, data from an open-ended variable of the DERIM survey, which is systematically administered to this population, was utilized. This variable encourages participants to freely express their experiences during the internship year (12).

Phase 2 involved familiarization with the data. Since this study articulated prior quantitative data with open narrative expressions, this phase served as an interpretive bridge between the two types of evidence. It allowed for the recognition of how individual discourses related to the structured dimensions of the questionnaire (safety, education, and decent work), and prepared the stage for preliminary coding, guided by theoretical constructs, while remaining open to emergent categories and preparing the ground for the dialectical contrast between what the numbers show and what the voices reveal (13).

In Phase 3 of the analytical process, preliminary coding was performed, guided by an interpretive-critical approach and by the three structuring axes of the individual questionnaire: 1) the right to personal safety and health, 2) the right to education, and 3) the right to decent work. This coding was carried out through an intensive reading of the open narrative discourses, with the goal of identifying meaningful units that reflected conditions, risks, or experiences during the medical internship. The discourse fragments were labeled with initial codes responding to both predefined categories and emergent inductive thematic areas, allowing for the articulation between qualitative data and the theoretical constructs of the instrument.

Phase 4 involved the development of analytical categories through a process of refining and selecting codes, during which the elements from the initial coding were contrasted with the quantitative data obtained in previous phases. This triangulation allowed for the validation of the internal coherence of the findings and strengthened the structural interpretation of the discourses.

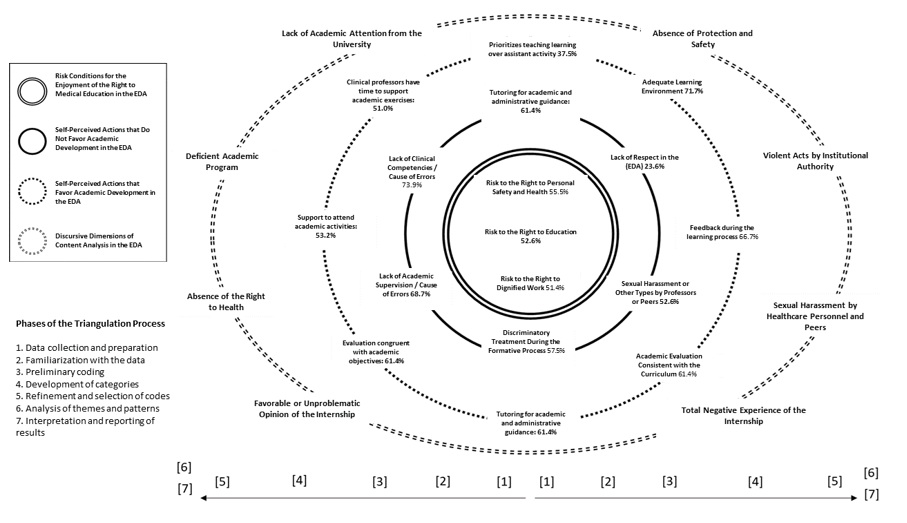

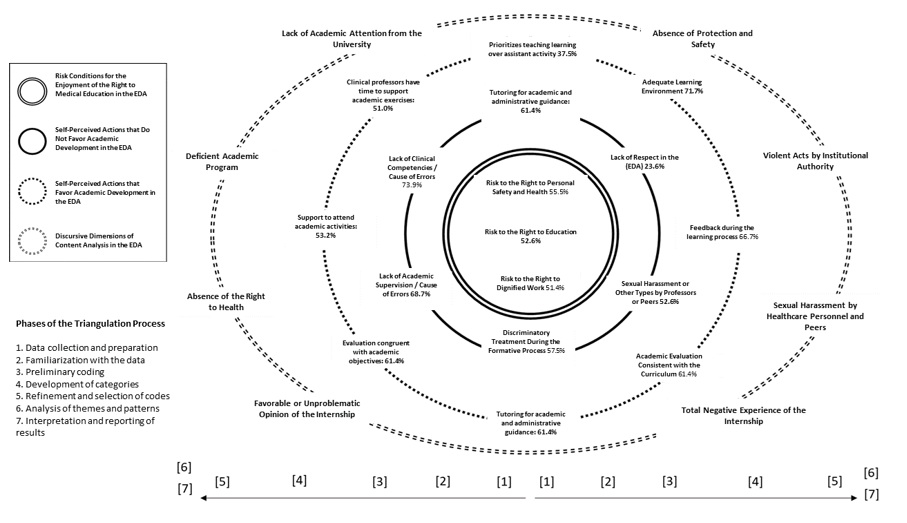

In Phase 5, the categories were consolidated by integrating them into a visual model of risks and conditions, represented in the circular image of the study. This model organizes the findings around three types of risk: to the right to personal safety and health (55.5%), to the right to decent work (52.6%), and to the right to education (50.2%). Each axis includes subcategories that were used as thematic codes in the subsequent analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Structural map of risks and conditions that

undermine the exercise of rights during the medical internship in Mexico. Basis

for mixed-method triangulation.

Figure 1.

Structural map of risks and conditions that

undermine the exercise of rights during the medical internship in Mexico. Basis

for mixed-method triangulation.

Note: Visual representation of

the main structural risks that affect the exercise of the rights to health,

personal safety, decent work, and education during the undergraduate medical

internship. The diagram organizes the findings into three concentric circles,

distinguishing risk conditions, actions that exclude the student from the

healthcare team, and educational deficiencies. Each radial axis groups specific

categories, such as lack of protection, institutional violence, lack of

academic supervision, and insufficient training in human rights. The

percentages reflect the prevalence of each type of risk in the studied

population, highlighting the urgency of transforming the training model towards

fairer, safer, and ethically sustainable frameworks.

Source: Own

creation.

In accordance with this approach, phases 4 and 5 of the methodological triangulation process were oriented towards the development of analytical categories that would allow for addressing the breadth of criteria, experiences, and issues expressed by the interns. Eight categories were defined, which were sufficient to organize the discursive content: 1) favorable opinion or no inconvenience regarding the completed period, 2) total negative perception of the lived experience, 3) perception of a deficient academic program, 4) lack or absence of university academic attention, 5) lack of protection and safety, 6) deterioration of the right to health, 7) violent acts by institutional authority, and 8) sexual harassment by healthcare personnel or peers.

Phases 6 and 7 involved the analysis of themes and patterns, as well as the critical interpretation and reporting of results. In this stage, representative texts of the structured dimensions were retrieved and presented, faithfully transcribed as they were stated by the interviewed interns, with the purpose of highlighting the conditions of vulnerability, exclusion, and precarization that affect the full exercise of human rights in the teaching-healthcare space.

To establish a framework for interpretation, an integral empirical and theoretical background was referenced to substantiate the relevance of evaluation through method triangulation. This approach recognizes research as a dynamic that integrates the analysis of structures, processes, and outcomes, as well as the understanding of the relationships involved in the implementation of actions and the differentiated perspectives of the actors. Together, these elements configure the project as a complex construct, permeated by hierarchical, technical, and epistemic relationships that demand a critical and situated reading of the training phenomenon (14).

Each category was rated and analyzed based on the discursive context of the open responses, establishing thematic and structural links with the dimensions of the theoretical construct. In cases where the argument exceeded the boundaries of a category, a second level of analysis was enabled to capture the complexity of the narrative. This procedure included critical reading, content analysis, and classification of the testimonies provided by the members of the cohort, also considering sociodemographic variables such as age and sex identified as male (M), female (F), in order to identify differential patterns in the internship experience.

This work is part of a larger project developed by OBEME, registered and approved by the Research and Ethics committees of the Public Health Institute at the Universidad Veracruzana, under the numbers CI-ISP-02-2023 and CEI-ISP-UV-R11/202. Throughout all phases of the study, the protection of the participants, the confidentiality of the data, and respect for informed consent were ensured. The authors declare that no identifiable data from the interviewed interns are presented in this article, and the materials used to integrate the analysis are held by the corresponding author.

Results

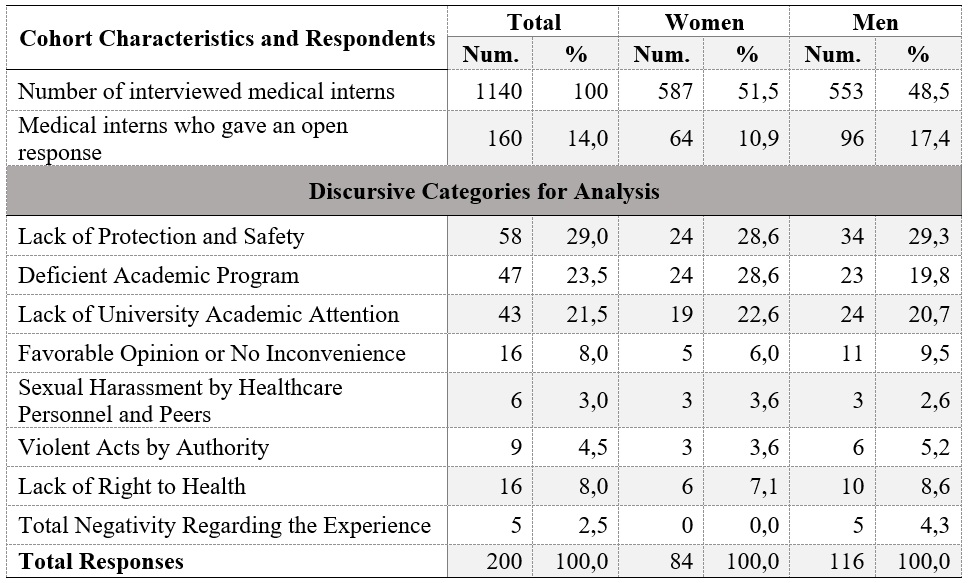

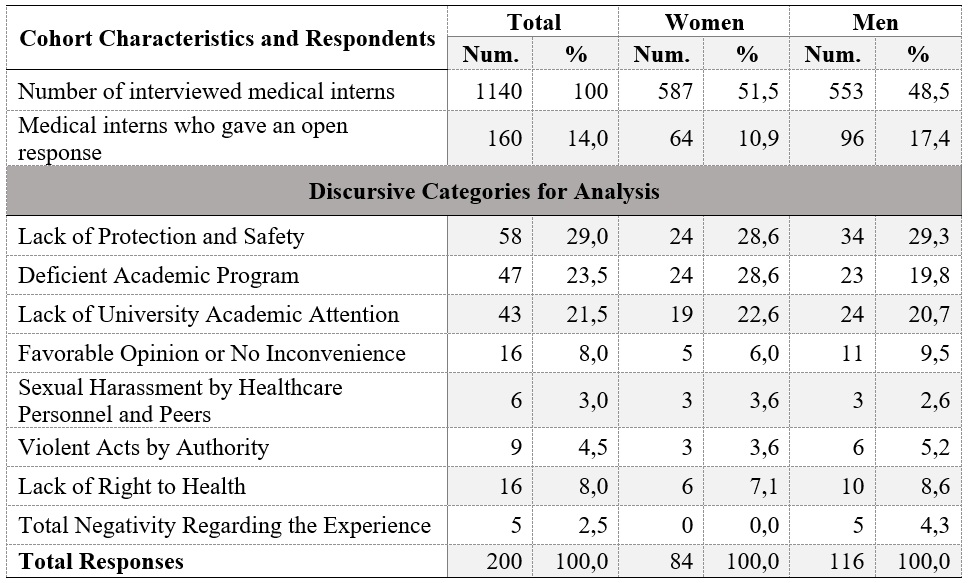

Between 2017 and 2022, a total of 1,140 undergraduate medical interns agreed to participate in the application of the DERIM survey. Of these, 160 (14%) chose to use the open-comment option at the end of the instrument, which allowed for spontaneous narratives about their training experience. This participation was proportionally higher among men, who represented 17.4% of their cohort, compared to 10% among women.

In the content analysis, the category "Lack of Protection and Safety" was the most representative, highlighting institutional vulnerability and the lack of minimum guarantees for the development of the medical internship. Next in frequency were "Perception of a Deficient Academic Program" and "Lack or Absence of University Academic Attention," both associated with the disconnection between training institutions and hospital settings. In contrast, the category with the least representation was "Total Negativity Regarding the Lived Experience," in which no expressions of disagreement were recorded from women, suggesting potential differential mechanisms of expression or silencing in the face of adverse experiences (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of Responses Given by Medical Interns According to Structured

Discursive Dimension via Methodological Triangulation. Veracruz, Mexico 2017-2022

Note:

The sum of the

discursive categories in the breakdown exceeds the number of medical interns

who provided comments, as some of them had the option to write a second

comment.

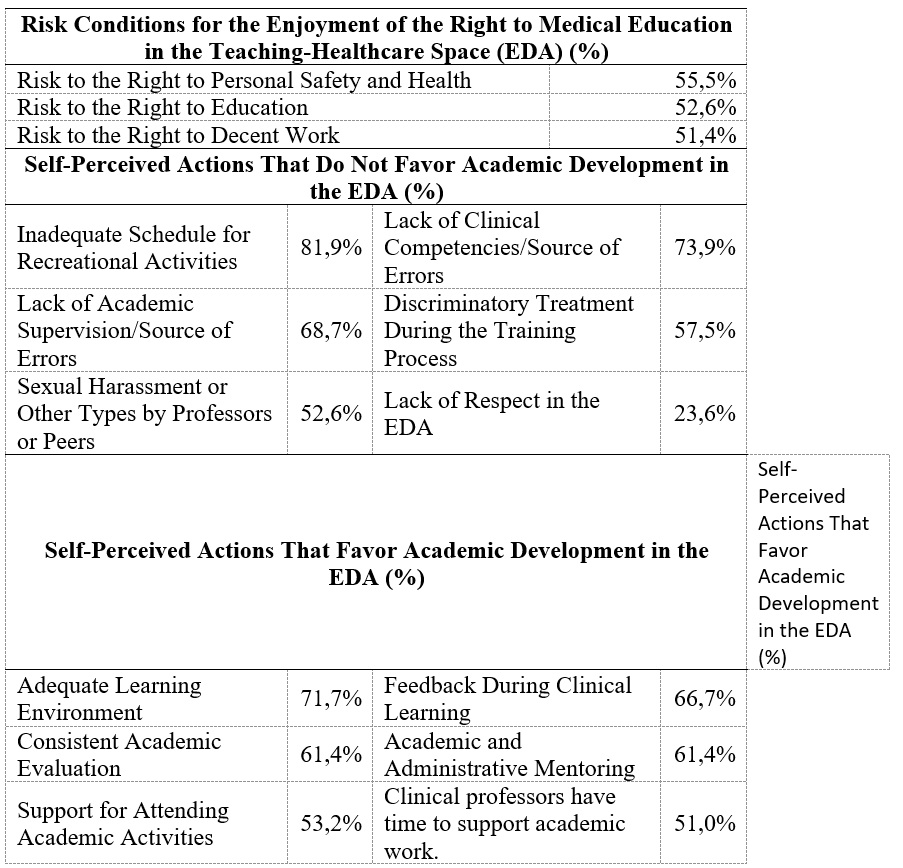

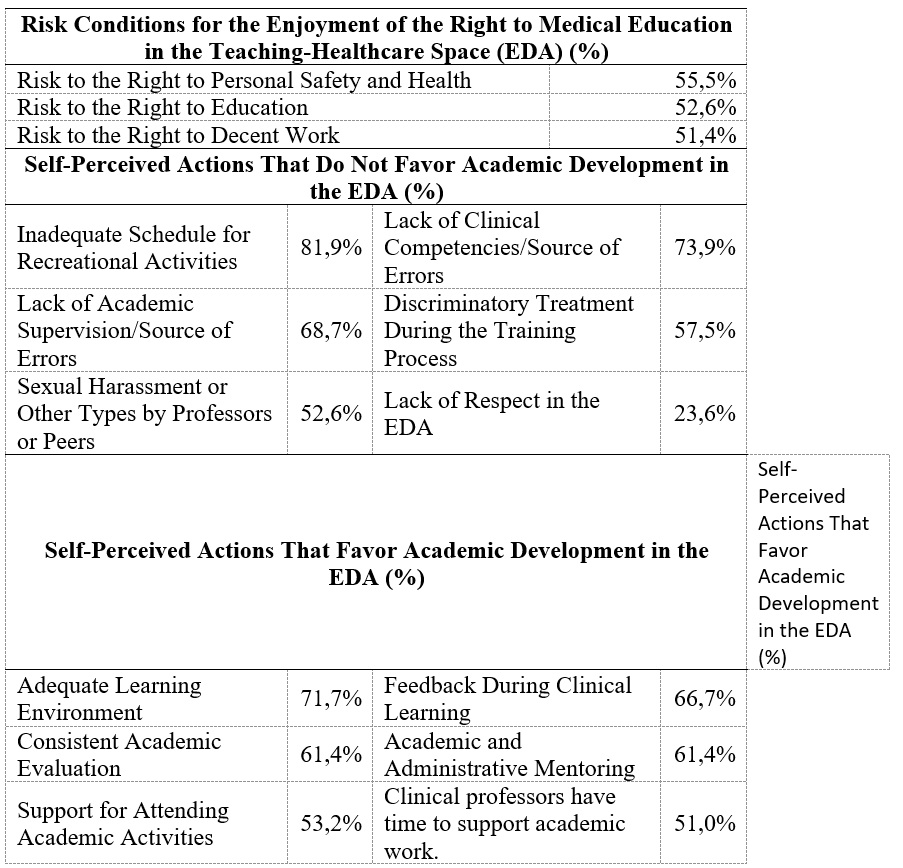

Since phase 1 of the methodological design required a solid empirical foundation to activate the dialogical interaction process and build analytical categories with broad interpretive scope, this section presents the statistical data used. As outlined in the methodological section, these inputs were extracted from two previous studies with the same population of medical interns in Mexico, allowing for the establishment of an empirical continuity line and strengthening the structural validity of the analysis. The incorporation of these quantitative data not only facilitated the preliminary identification of recurring issues during the medical internship but also enabled the contrast and enrichment of qualitative findings through a methodological triangulation approach. This strategy helped to highlight the conditions that affect the full exercise of the right to medical education, by linking statistical evidence with critical narratives that reveal normalized institutional practices and formative structures in need of transformation (Table 2).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Risk Conditions and Self-Perceived Actions That Favor and

Do Not Favor Academic Development in the Teaching-Healthcare Space, 2017-2022

EDA: Teaching-Healthcare Space.

Favorable Opinion or No Inconvenience Regarding the Internship

This category was mentioned by 16 students (8% of the total open responses), with a predominance of male participants. The expressions collected in this group reflect a positive evaluation of the internship, although in some cases, there are paradoxical or ambivalent nuances. A representative example states: “Excellent place to carry out the internship, as well as a future medical residency” [M/26]; while another expression, though complimentary, reveals an implicit contradiction: “It was an excellent year where I learned a lot, but I definitely wouldn’t do it again, although I recommend hospital ‘X’…” [M/24]. This type of comment suggests that, despite adverse conditions, some students recognize the institutional prestige or the formative value of the clinical space. The women who fell into this category expressed satisfaction with their experience, but without providing contextual or reflective elements to delve deeper into the reasons behind this evaluation.

Total Negativity Regarding the Lived Experience During the Internship

This category was exclusively expressed by five male students, who voiced an absolute disapproval of their experience in the medical internship. The narratives collected reveal deep distress, marked by perceptions of labor exploitation, lack of meaningful learning, and a hostile institutional environment. One particularly striking expression states: “The internship is horrible, it’s a year of cheap labor, no learning, and a hostile environment designed to make you feel bad and want to quit. The university doesn’t even care about its students, they let them be violated, starve, and cry, they do nothing for their students” [M/25]. Although extreme in its formulation, this testimony highlights a complete rupture between formative expectations and lived reality, as well as an explicit denunciation of institutional negligence.

Another recurring comment in this category ("I wouldn’t do it again" [M/24]) is repeated by the other respondents and consolidates a pattern of rejection that questions not only the quality of the formative process but also the ethical legitimacy of the current institutional model. The absence of women in this category could be interpreted as an indicator of silencing, resignation, or discursive redirection toward other forms of expression, which warrants further exploration in future analyses.

Lack of Protection and Safety

The category "Lack of Protection and Safety" was the most frequent among the discursive responses, representing 29% of the total. The expressions collected in this category reveal a widespread perception of institutional and public insecurity that directly affects the physical, emotional, and professional integrity of the medical interns. The testimonies document multiple fronts of vulnerability: from the lack of basic supplies for dressing and working to exposure to extreme violence both within and outside the hospital environment. One student states: “There was a shooting outside the hospital” [F/24]; while another refers to: “Patients were executed on several occasions. No one is completely safe” [M/24], highlighting that the clinical space does not guarantee minimum safety conditions.

Additionally, violations of current national regulations are documented, such as the failure to provide uniforms, the denial of access to healthcare services, the omission of food and medicine, and the imposition of prohibited tasks such as transfers without legal backup. One testimony clearly summarizes this: “No gowns or uniforms were provided… We couldn’t register in the system… We were forced to do transfers even though it was prohibited” [M/24]. These conditions not only violate the right to personal safety but also the full right to medical education, by preventing a dignified, orderly, and protected formative environment.

The complexity of the expressions in this category reveals deep institutional paradoxes, such as denying healthcare services to the very trainees who actively participate in medical care. Despite this, acts of solidarity emerge among students, such as when a colleague had a seizure and, in the face of the institution’s refusal to conduct a tomography, his peers raised money to cover the test [F/29].

Exhausting work conditions are also reported, such as shifts lasting up to 36 continuous hours, which compromise clinical effectiveness and the physical and mental health of the students: “Reduce the workday, eliminate the post-guard shift… There’s no longer the capacity to continue performing activities effectively” [F/24]. Finally, direct expressions of denunciation are recorded that require no further interpretation: “My car was robbed” [M/24]; “Armed robbery” [M/26]; “No more medical interns in unsafe conditions that jeopardize their lives” [M/24].

These findings create a critical scenario that demands urgent interventions regarding safety, regulations, and the dignification of the formative space, recognizing that the medical internship can no longer operate under conditions that endanger the life, health, and fundamental rights of those who undertake it.

Perception of a Deficient Academic Program

This category was frequently expressed by the participants and represented 23.4% of the total discursive responses. The narratives collected reveal sustained criticism of the educational model implemented during the medical internship, characterized by the absence of pedagogical planning, the lack of committed teachers, and the non-existence of formal evaluation mechanisms. One student summarized this as follows: “Although hospital ‘X’ is a good institution for doing the internship, I think it lacks a lot of organization and logistics… There is no teaching, nor are there professors who really provide quality classes or do so consistently” [M/25].

The expressions also reveal a disconnection between the available infrastructure and the effective pedagogical use of the clinical spaces. While the willingness of some attending physicians and the quality of the facilities are acknowledged, the ineffectiveness of the Education Department, the lack of courses, the absence of evaluations, and the omission of a formal curriculum are denounced: “The Education Department… does not care at all… We don’t receive training courses or classes… The hospital has excellent facilities… but there’s no institutional response” [F/23].

This category also articulates an explicit demand for integral training, which includes participation in clinical procedures, teacher guidance, and recognition of the student as a subject in training. One extensive testimony expresses this clearly: “Improve the teaching process… give us the opportunity to participate in medical events… examine patients, make diagnoses, give treatments… participate in surgeries and obstetric care under supervision… consider us as medical trainees… not as messengers or administrative staff” [M/29].

These voices reveal a rupture between the institutional discourse of medical training and the real practice of the internship, where self-learning, improvisation, and the delegation of operational tasks replace pedagogical support. The category demands a profound restructuring of the educational model, ensuring minimum conditions for teaching, clinical supervision, and respect for the formative process as a professional right.

Lack or Absence of

University Academic Attention

The category “Lack or Absence of University Academic Attention” was mentioned frequently and represented 21.5% of the discursive responses. The expressions collected in this category reveal an institutional rupture between training institutions and hospital settings, where students perceive abandonment, pedagogical disconnection, and the absence of academic supervision. One testimony clearly summarizes this: “It would be ideal if the faculty constantly supervised students’ time at the hospital, they abandon you and never supervise... The priority is to get the work done and almost never teaching” [M/25].

Additionally, punitive practices are reported, replacing formative support with punishment mechanisms used to compensate for the lack of operational staff. These practices, instead of promoting learning, generate stress, exhaustion, and the use of medication to stay awake, as one student notes: “The punishments are just to justify the lack of staff... Being tired leads to using medication... more stress” [M/27].

The narratives also articulate a structural critique of the university's role, as it does not guarantee dignified treatment or the recognition of the student as a subject in training. It is reported that in many services, interns are treated as administrative assistants, without classes, evaluations, and with grades assigned subjectively: “The university should focus on ensuring that students are treated as what they are—students... The education coordinator doesn’t focus on learning... The grades are completely subjective” [F/29].

This category reveals a profound institutional omission, where the university delegates its training responsibility to the hospital without mechanisms for follow-up, supervision, or guarantees of educational quality. The lack of university academic attention not only violates the right to education but also perpetuates a medical training model based on operational subordination, pedagogical invisibility, and the precarization of the training process.

Deterioration of the Right to Health

The expressions collected in this category reveal a critical dimension of the medical internship: the systematic deterioration of the students' right to health, who, paradoxically, are part of the healthcare system without receiving minimum guarantees for their physical, mental, and emotional well-being. This category not only denounces institutional omissions but also highlights an ethical crisis in the training model, where the student is treated as an operational resource rather than as a subject of rights.

The testimonies reveal exhausting working conditions, the lack of dignified rest areas, and profound neglect in emotional support: “I believe more attention should be paid to the mental health of students… On many occasions, we are treated without dignity and they forget that we are also human beings” [F/24]. This statement encapsulates institutional abandonment and the dehumanization of the formative process, where long working hours and structural indifference cause harms that go beyond the academic realm.

Additionally, inaction from responsible figures, such as heads of education, is denounced. Their neglect not only affects the quality of education but directly contributes to the emotional harm of the interns: “The head of education… was never attentive… he only cared about lowering our grades… the environmental conditions at the hospital caused emotional distress… even situations that put their lives in danger” [M/24]. This testimony reveals that the deterioration of the right to health is not a collateral effect but a direct consequence of institutional negligence and the lack of protection mechanisms.

This category must be addressed as a structural alert, calling universities, hospitals, and health authorities to account for their shared responsibility in ensuring dignified conditions for those training in their spaces. The student’s right to health cannot be subordinated to the operational logic of the hospital system; it must be recognized as a central axis of the educational process, inseparable from educational quality, professional ethics, and human dignity.

Sexual Harassment by Healthcare Personnel and Peers

The category “Sexual Harassment by Healthcare Personnel and Peers” includes testimonies that reveal violent, systematic, and deeply damaging actions directed at students in a situation of inequity and subordination within the teaching-healthcare space. The expressions collected not only denounce direct assaults but also institutional retaliation in response to attempts to report, creating an environment of impunity and silencing. One testimony clearly expresses this: “Our head of education and the interns had conflicts almost all year… Several of my female peers reported him for sexual harassment… The rest of the year, we received mistreatment and insults as retaliation” [M/25].

The recurrence of these experiences, as highlighted by another student —“every day I was sexually harassed by hospital staff and fellow interns” [M/26]— reveals that harassment is not an isolated incident, but a normalized practice that is reproduced at different hierarchical levels, including coordinators, residents, and peers. In some cases, it is reported that harassment specifically targets male students, further widening the vulnerability spectrum: “At hospital ‘X,’ there is harassment by the intern coordinator, especially when the intern is male. There is psychological violence and harassment” [M/25].

Sexual harassment, as a form of structural violence, manifests through comments, jokes, gestures, and behaviors that degrade the professional and human dignity of the student, especially when intersecting with gender identities and sexual orientation. One testimony illustrates this: “They should talk to the attending physicians and tell them to stop using derogatory terms for gay interns… the gynecologist ‘X’ made jokes and inappropriate comments” [M/26].

From an academic and ethical perspective, this category must be addressed as a serious violation of the right to integrity, equality, and education free of violence. Sexual harassment in the teaching-healthcare space not only affects the mental and emotional health of the student, but also compromises the legitimacy of the formative process and the institutional responsibility to guarantee safe spaces. Additionally, the difficulty in reporting —due to fear of retaliation, lack of protocols, or institutional indifference— reinforces the need for effective prevention, care, and redress mechanisms that recognize the structural dimension of the problem and promote a culture of respect, equity, and justice in medical education.

Violent Acts by Authority Figures

Although this category was less frequent in quantitative terms, its content reveals a deeply critical aspect of medical internships: the existence of violent acts perpetrated by authority figures, which affect the integrity, academic development, and professional dignity of students. The statements collected, though brief, suggest a pattern of institutional abuse manifested in threats, physical aggression, unjustified punishments, and degrading treatment. One student expresses this forcefully: "Poor treatment from the teaching department... to the point of threatening my academic future" [H/24], while another directly reports a "physical assault by a resident" [M/24].

These experiences, although not always explicitly verbalized, form a scenario of structural violence, where hierarchical power is exercised without ethical control mechanisms or guarantees of protection. The request for “anti-harassment and workplace abuse security support” [M/27] highlights the urgency of establishing institutional protocols that recognize and address these forms of violence, often invisible in traditional medical culture.

A more extensive testimony offers an ambivalent perspective, where the student acknowledges positive aspects of the clinical environment but also denounces practices that undermine their formative condition: “We had situations of unjustified punishment, very long working hours… harassment situations, inappropriate comments, as well as attitudes aimed at making us feel inferior because we were interns” [M/25]. This ambivalence should not be interpreted as a contradiction, but as evidence of the normalization of institutional violence, where the student learns to coexist with mistreatment as part of the educational process.

From a critical bioethical perspective, this category directly challenges training and hospital institutions about their shared responsibility in perpetuating authoritarian, punitive, and dehumanizing practices. The violence exercised by authority figures not only violates the right to education but also perpetuates a medical model based on uncritical obedience, hierarchical submission, and the exclusion of ethics as a core element of training. Reporting these acts is not merely an exercise in narrative justice but an ethical demand to transform the medical internship into a space of dignified, safe, and emancipatory training.

Analytical Conclusion of Results: Between Structural Denunciation and Ethical Urgency

The results presented shape a complex and alarming panorama regarding the conditions faced by undergraduate medical interns in Mexico. The eight discourse categories analyzed reveal not only individual experiences of mistreatment, abandonment, and violence but also institutional structures that systematically reproduce the violation of fundamental rights in the teaching-assistant space. From the absence of protection and safety to sexual harassment and violent acts by authorities, an institutional culture is recorded that has normalized suffering as part of the formative process.

This scenario cannot be interpreted as a mere sum of isolated cases but as a reflection of an educational model that has historically functioned in alignment with the logic of subordination, obedience, and labor exploitation. The precarization of the right to health, the invisibility of academic support, and the negligence toward the professional dignity of the student form an educational model that contradicts the ethical, pedagogical, and humanistic principles that should guide medical education.

The students’ narrative not only denounces but also challenges. In their voices, there is an urgent demand for recognition, justice, and transformation, which cannot be ignored by universities, hospitals, or health authorities. The medical internship, far from being a stage of professional consolidation, has become for many a space of risk, exclusion, and institutional violence.

In this context, a deep reflection on the need to build a culture of peace and non-violence in medical education becomes essential, one that recognizes the student as a subject of rights, promotes horizontal and ethical relationships, and ensures safe, formative, and dignified environments. This culture cannot remain an abstract ideal but must become a concrete demand that permeates the curriculum design, institutional management, and clinical practice.

Critical bioethics, as an interpretative framework, allows for the visibility of tensions between the formative discourse and the lived reality, providing tools to rethink the medical internship as a space for emancipation, mutual care, and epistemic justice. This conclusion of results not only documents the current conditions but also opens the door to a transformative discussion that must be taken up with responsibility, commitment, and political will by all involved actors.

Discussion

The present study aimed to analyze and interpret the findings related to the formative process during the medical internship year, based on the discourse of students from a public university in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Through this methodological approach, empirical evidence is strengthened by integrating qualitative and quantitative data in order to propose more effective and ethically sustainable intervention measures. Despite the relevance of the topic, no prior studies with a qualitative approach specifically examining human rights within the context of the medical internship were identified, revealing a critical gap in the national literature and opening a necessary line of research in the field of medical education.

However, there is sufficient documentation on the hostile conditions faced by medical trainees, in which the demands inherent to the profession intertwine with institutional practices that reproduce violence, discrimination, harassment, and work overload (15). These conditions not only affect the student’s physical and emotional well-being but also increase the risk of clinical errors, compromise the quality of care, and undermine the ethical foundation of medical practice (16). In this context, the medical internship emerges as a space of tension between professional training and human dignity, calling for a profound reflection on existing educational models and the urgent need to build an institutional culture grounded in peace, respect, and non-violence.

The results of this study reveal an adverse educational context characterized by the systematic violation of fundamental rights and by a clear gap in the full exercise of human rights within medical education. The narratives analyzed show not only unfavorable clinical conditions but also insufficient institutional co-responsibility on the part of participating universities, expressed through pedagogical neglect, ethical omissions, and structural disarticulation. This finding provides coherence and support to the quantitative evaluations conducted by OBEME since 2017, from which the qualitative discourses analyzed here were derived (17).

The convergence between quantitative and qualitative data reinforces the critical validity of this study, as it demonstrates that the conditions reported by students—violence, discrimination, harassment, work overload, and institutional negligence—do not constitute isolated incidents but rather structural expressions of an educational model that reproduces dynamics of exclusion and subordination. Within this framework, the medical internship becomes an ethical risk space in which students are treated primarily as operational resources rather than as rights-bearing subjects, and where the professionalization process unfolds under conditions that contradict the fundamental principles of bioethics, educational justice, and human dignity (18).

This finding calls for a critical re-examination of the role of educational institutions, which cannot continue to delegate their formative responsibility without mechanisms of supervision, protection, and support. Medical education in Mexico requires a profound transformation, aimed not only at improving academic indicators but also at guaranteeing safe, ethical, and humanizing environments that promote respect, equity, and mutual care as central axes of the formative process.

In attempting to recover favorable or unproblematic opinions about the medical internship, an absolute minority was observed, predominantly male, whose comments were limited to general evaluations without further depth, such as “it was an excellent place to do the internship.” On the other hand, women expressed satisfaction only with the physical facilities of the medical unit, without expanding on pedagogical or institutional aspects. This might suggest less agreement or greater critical reservation regarding the lived experience.

However, in contrast, it was also men who expressed the most negative and forceful opinions, with phrases such as “it’s horrible… hostile environments… they don’t care about their students” or “I wouldn’t do it again,” revealing a polarization in the expression of dissatisfaction and a possible difference in the mechanisms of complaint between genders. This pattern contrasts with the findings reported by Cuevas-Gabriel et al. (19), who documented that the overall satisfaction rate in the medical internship was estimated at 81.4%, with no significant differences related to gender (p = 0.370), and only age was found to be significant (p = 0.022).

Regarding the dimension of the absence of protection and safety for students, this was the most mentioned category, predominantly among men. The discourse reveals scenarios of institutional neglect both inside and outside the hospital: lack of appropriate clothing, omission in providing meals, and absence of medical care mechanisms for the interns themselves. Paradoxically, the right to health is violated for those being trained to provide it, forcing them to use their own resources to address serious health issues that the institution did not attend to. This reality coincides with the observations made by García Hernández and Alvear Galindo (20), who warn that medical training in hospital units can become a violation of human rights, generating illness and affecting the health of students by failing to guarantee ethical, safe, and dignified conditions for their professional development.

Regarding the dimension of the perception of a deficient academic program, this was expressed more frequently by women, although both men and women agreed in pointing out the lack of quality teaching, the absence of a formal curriculum, and the lack of relevant evaluations. The narratives reveal that, in the absence of professors responsible for the formative process, students are forced to resort to a self-learning methodology, based on presenting topics on their own without feedback or academic supervision. This situation not only undermines the right to structured medical education but also perpetuates an improvised, assistance-based training model lacking pedagogical support.

These findings coincide with the reports from OBEME, which document how the medical internship in Mexico continues to operate under a scheme where assistance work predominates over the educational process, and where the absence of university professors in hospitals prevents the fulfillment of academic objectives established in the curriculum (21).

Students mention the absence of training specifically directed at them, as well as the prevalence of administrative, technical-medical, and even messenger tasks, which are imposed above supervised clinical care. This dynamic reveals a deviation from the formative purpose of the medical internship, where the student is treated as an operational resource rather than as a person in training. The most concerning aspect is the perception of institutional abandonment, both by teaching supervisors and the faculty, who, despite being informed of these conditions, have not provided a response or support.

This situation not only violates the right to quality medical education but also represents a breach of the right to health for patients, by training future doctors with obvious gaps in clinical knowledge, which increases the risk of medical errors. There is evidence showing the benefits of establishing evaluation mechanisms in the clinical workplace and feedback, despite the challenges posed by the formative hospital environment itself, such as work overload, time saturation, and the lack of capacity of teaching staff (22, 23).

Regarding the dimension addressing the lack of university academic attention, i.e., the perception of abandonment and lack of commitment from the training institution, this was one of the most frequently mentioned by students. They request that the university fulfill its formative responsibility and constantly supervise the internship experience in hospitals, ensuring that they are treated as what they are: students in training. According to the testimonies, this institutional omission leads to excessive workloads, where punishments are used as a mechanism to cover staffing shortages by imposing activities that hinder clinical learning. The most alarming aspect is that this dynamic has encouraged self-medication among students, who resort to substances to stay awake, which poses a serious threat to their physical and mental health.

Various findings indicate that we are dealing with a student population that is vulnerable during their hospital internship, which requires immediate attention to address the gaps and deficiencies resulting from institutional neglect by the training universities. It is widely documented that the transition to clinical practice increases anxiety levels among medical students, that long work hours and night shifts contribute to physical and emotional exhaustion, and that vertical hierarchical relationships and the lack of adequate academic supervision intensify stress. All of this directly affects the mental health and academic performance of interns, which not only compromises their well-being but also the quality of their professional training and future ethical practice of medicine (24).

The category referring to the deterioration of the right to health reveals a critical dimension of the medical internship, where students face not only adverse working conditions but also direct impacts on their mental health. In addition to the previously mentioned findings—such as self-medication to stay awake—the complaint of degrading treatment, lack of adequate rest spaces, and work overload stand out, all elements that create a hostile clinical environment. The most serious issue is that this situation develops under the indifference of the training institution, which, according to the testimonies, has never shown interest in understanding or addressing these conditions. This omission represents a structural violation of the right to health, both in its physical and emotional dimensions, and calls for a profound revision of the current educational model.

On the other hand, the dimension referring to sexual harassment by healthcare staff and peers is evident in the discourse of both women and men, with women—along with those who self-identify as gay—reporting having suffered these assaults more frequently. The testimonies indicate that they reported these incidents "at the central level," without any observable consequences for the aggressors, which led to institutional reprisals, mistreatment, and insolence from those in positions of hierarchical power. This impunity not only perpetuates violence but also reinforces a culture of silencing and lack of protection within the clinical space.

Regarding violent acts by authority figures, while explicitly expressed only on rare occasions, they are implicitly observed in most of the discourse classified in the previous categories. The normalization of mistreatment, the use of punishment as a control mechanism, and the delegation of non-formative tasks create an institutional environment where violence is exercised in a structural, silent, and persistent manner.

These findings align with those reported by Granados Cosme et al. (6), who documented a prevalence of sexual harassment of 83% among undergraduate medical interns in hospitals in Mexico City, with women being most affected. The study indicates that complaints do not lead to consequences for the aggressors, which increases the risk of students abandoning their careers and negatively impacts their professional, emotional, and ethical development.

Conclusions

Given the findings of this study, it is asserted that the formative conditions experienced by undergraduate medical interns in the Mexican hospital context are deeply removed from the full exercise of their human rights. Through discourse analysis, institutional practices that reproduce insecurity, mistreatment, structural violence, and academic abandonment are highlighted, creating a clinical environment that contradicts the fundamental principles of ethical, dignified, and humanizing medical education.

The lack of formality in academic practice, the absence of teaching supervision, excessive workloads, and the impact on the physical and mental health of students constitute systematic violations of the right to education, health, and personal integrity, which must be recognized as structural issues rather than exceptions. The normalization of these conditions in the medical internship reveals an ethical and pedagogical crisis that directly challenges educational institutions, hospital authorities, and regulatory bodies.

This study makes an urgent call to the university responsible for this work, a preventive call to both public and private universities, as well as to the governmental bodies responsible for medical training, urging them to assume their institutional responsibility and ensure educational processes based on respect, equity, and ethical support. The slogan "For a culture of peace and non-violence" can no longer remain an empty motto; it must be translated into concrete policies, protection protocols, curricular reforms, and supervision mechanisms that dignify the formative experience of future healthcare professionals.

In sum, this work not only documents a concerning reality but also proposes a critical re-examination of the medical internship as a formative space, where the respect for human rights, educational justice, and critical bioethics should be guiding principles to transform medical education in Mexico.

Suggestions

Based on the findings of this study, the following strategic actions are proposed to ensure the respect, dignity, and protection of medical trainees during their time in teaching-assistive units:

Design and implementation of public policies with a human rights approach. Develop and implement public policies that require medical education institutions to assume their comprehensive responsibility in the training process. These policies should guarantee a quality, ethical, and humanizing medical education, in strict adherence to the enjoyment of human rights by students, from their admission to the completion of their training, including their stay in teaching-assistive units. Effective interinstitutional collaboration between universities and healthcare institutions must be promoted to align pedagogical objectives, dignified working conditions, and ethical supervision mechanisms.

Creation of an interinstitutional vigilance and protection committee. Establish a permanent committee composed of representatives from the educational institution and the receiving medical unit, whose primary function will be to monitor, ensure, and document the effective enjoyment of the human rights of undergraduate medical interns. This committee must have the authority to intervene in cases of violence, harassment, negligence, or academic abandonment, as well as issue binding recommendations that promote safe, formative, and respectful environments.

Academic supervision protocols and ethical support. Design and implement institutional protocols that ensure the active presence of university faculty in medical units, with clear responsibilities for academic supervision, clinical feedback, and emotional support. These protocols should include mechanisms for formative evaluation, dignified rest spaces, and minimum guarantees for the physical and mental health protection of students.

Continuous training in critical bioethics and a culture of peace. Incorporate specific content on critical bioethics, human rights, a culture of peace, and prevention of institutional violence into curricula and staff training for medical and teaching personnel. This training should be mandatory, transversal, and contextualized, aimed at transforming hierarchical relationships into pedagogical bonds based on respect, empathy, and shared responsibility.