Introduction

There are groups especially vulnerable to sex work. These include migrants, who may be forced into it in countries where they lack access to jobs; individuals with addictions, who use it to finance substance consumption; and the LGBTIQ+ population, for whom it may become a source of income in contexts of discrimination and labor marginalization (1,6-8).

A study conducted in Europe in 2009 revealed that 6% of sex workers were transgender women and 7% were cisgender men (9). These groups face higher risks of violence and discrimination, reinforcing the need to ensure their access to healthcare services and a discrimination-free environment (10-13).

Within the LGTBIQ+ population, there are subgroups that are difficult to reach, known as hidden populations, which are often characterized by social isolation, mistrust of authorities, and stigma (12). The lack of engagement with these groups limits the understanding of their needs, which is why strategies based on trust-building and the establishment of collaborative relationships with LGBTIQ+ groups are required. This allows for the development of targeted programs and services addressing their unique needs (14).

The prevalence of sex work among men who have sex with men (MSM) varies significantly by region, ranging from less than 1% to more than 30% (10,15,16). Various studies indicate that MSM are more likely to engage in sex work than men who have sex with women (11-13). Among the factors driving them into this practice are economic necessity, labor discrimination, and lack of access to social and healthcare services (17). MSM often face high levels of stigma, which hinders their access to employment and exposes them to higher risks of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV. Additionally, sex work may serve as a form of social connection, although it carries significant risks such as violence and exploitation (18).

Despite global advancements, there are still significant gaps in understanding sex work among MSM in Latin America, particularly in Colombia. To date, there are no multicity comparative analyses that simultaneously integrate sociodemographic variables, substance use, and personal histories of MSM engaged in sex work, while also considering three contrasting urban contexts (Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali). This allows for exploration of regional differences and similarities, utilizing a sampling design aimed at hidden populations, such as Respondent-Driven Sampling (RDS), which enhances representativeness and reduces bias associated with conventional recruitment methods. In light of this, the focus of this study was to analyze the sociodemographic, substance use, and personal factors associated with payment for sexual relations among MSM.

Methodology

Design and Context

A cross-sectional study was conducted, nested within the project on sexual behavior and HIV prevalence among MSM in Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali in 2019 (19). A total of 1,298 MSM from three cities in Colombia—Medellín, Bogotá, and Cali—participated.

Population and Sample

All participants were men over the age of 18 who reported having had at least one sexual contact with another man in the past 12 months and who resided in one of the selected cities for the study. A respondent-driven sampling (RDS) method was used, with an initial selection of 9 seeds (3 per city), who then recruited other members of their social network. This data collection technique is the most appropriate for working with groups whose total population is unknown and difficult to access, and for which there is no available sampling frame (20). It is used because it allows for a random selection of participants through the target population’s social network and can increase the representativeness of the sample.

Sample Size and Power

The defined sample size was 1,298 participants distributed across Medellín (n = 446), Bogotá (n = 438), and Cali (n = 414). The calculation was based on an expected 15% prevalence of sex work among MSM, with a 95% confidence level, a 3% margin of error, and a design effect (deff) of 2. Given the use of RDS, the sample size required under this assumption was at least 1,200 participants. Therefore, the obtained sample ensures a statistical power greater than 80% to detect a 5% difference in proportions between the three cities.

Instrument

An adapted survey was used, based on guidelines for behavioral surveys in populations at risk of HIV, as defined by Family Health International. This was adjusted in Colombia by a group of experts from the funding organization (21). The survey consisted of fourteen sections: 1) social and demographic characteristics, 2) health and access to the General System of Health Social Security, 3) sexual and reproductive history, 4) stable male partner, 5) occasional partners or casual contacts, 6) sexual relations with women, 7) sex work, 8) payment for sexual relations, 9) knowledge and attitudes towards condoms and lubricants, 10) STIs, 11) knowledge, opinions, and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, 12) testing, 13) stigma and discrimination, and 14) social networks.

Variables

The outcome variable for this study was payment for sexual relations, defined by the following question: "In the last twelve months, have you received money or an incentive in exchange for sexual relations?" The independent variables were sociodemographic factors: age, household economic level, marital status, household composition, income, occupation, educational level; substance use factors (alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, poppers, ecstasy, and Viagra); and personal factors: HIV testing, HIV status, STIs, degree of vulnerability, condom use, and discrimination.

Data Analysis

Relative and absolute frequency measures were calculated for each of the characteristics analyzed using the RDSAT software. To assess the association between sociodemographic, substance use, and personal factors of the participants with sex work, the chi-square (χ²) test of independence was used. In cases where expected cell counts were <5, Fisher’s exact test was applied. Associations were considered significant if the p-value was <0.05. Prevalence ratios with their corresponding confidence intervals (95% CI) were also estimated. In the multivariate analysis, a model was constructed using the Poisson distribution with a log link and robust estimation. The variables included in the model were those that were significant (p < 0.05) in the bivariate analysis for each of the study cities.

Error and Bias Control

To reduce confounding bias, potential confounding variables associated with both the exposure and outcome (age, educational level, and income) were included in the models. Information bias was controlled by standardizing the data collection instrument and training field staff, while selection bias was minimized using the RDS methodology, which weights the probability of each participant’s inclusion based on the size of their social network.

Ethical Considerations

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the CES University in a session on February 19, 2019. The study followed the requirements of the Scientific, Technical, and Administrative Standards for Health Research, in accordance with Resolution 8430 of October 4, 1993, from the Ministry of Health of Colombia, classified as research with minimal risk (22).

Results

General Characteristics of MSM in the Three Cities

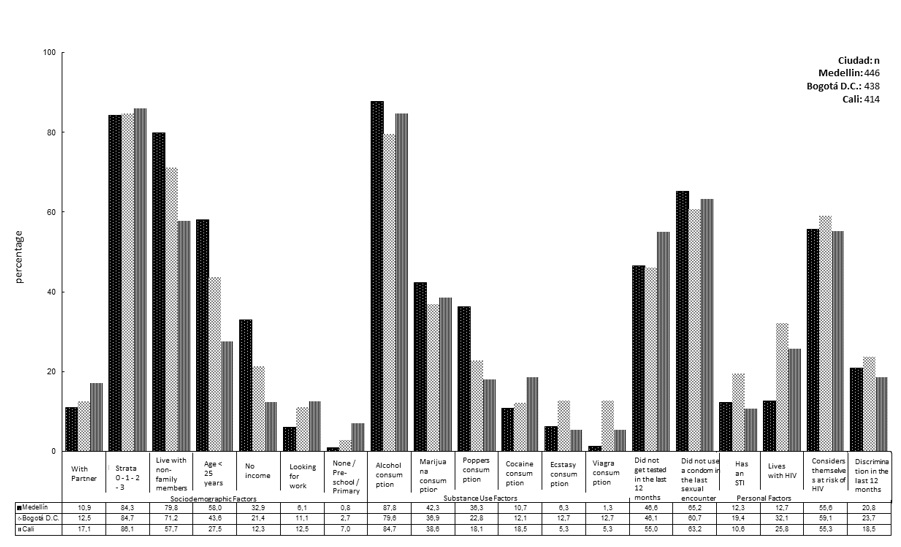

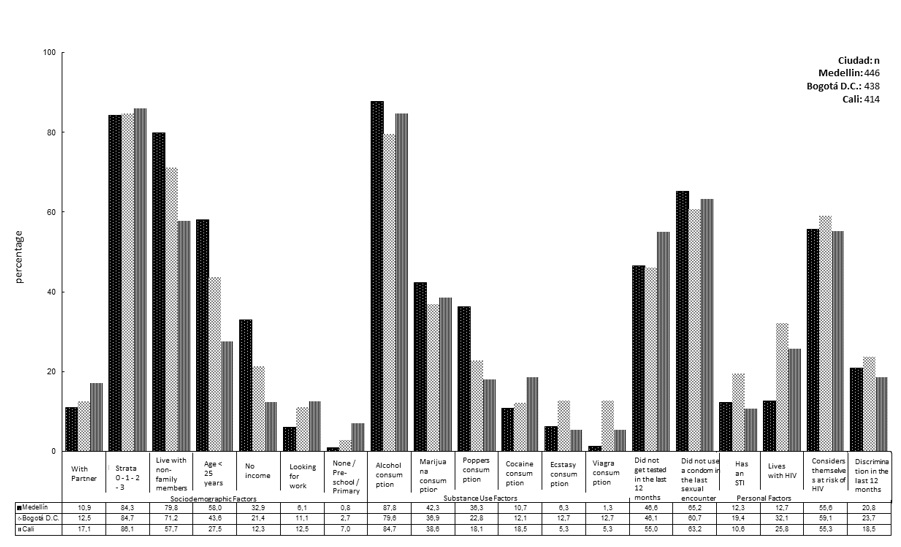

The sample consisted of 1,298 MSM, distributed across Medellín (446), Bogotá (438), and Cali (414). Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, more than 84% of participants in all three study cities lived in households from low-middle socioeconomic strata (0, 1, 2, and 3) and reported living with individuals who were not family members. In the city of Cali, it was found that one in every ten MSM had not attended school, or had only studied up to elementary school (Figure 1).

Regarding the consumption of psychoactive substances, more than 79.6% of participants in all cities reported alcohol consumption, with a higher prevalence in Medellín. Concerning certain illegal substances, such as marijuana, poppers, cocaine, and ecstasy, all showed consumption rates higher than 10%, indicating that at least one in every ten MSM consumes an illegal psychoactive substance. The most commonly used substances were marijuana (36.9%-42.3%) and poppers (18.1%-36.3%). Another notable aspect was the consumption of Viagra, particularly in Bogotá, where it was reported by 12.7% (Figure 1).

In terms of personal characteristics, one in every ten MSM reported having had an STI in the last 12 months (10.6%-19.4%), with a higher prevalence in Bogotá compared to Medellín. Notably, when conducting rapid and confirmatory HIV tests as part of the study, the HIV prevalence was found to be higher than self-reported rates. Over 56% of participants reported not having been tested for HIV in the last 12 months. Similarly, 55.6%-59.1% of the participants reported having some degree of HIV vulnerability across the three study cities.

Regarding discrimination, 2 in every 10 MSM experienced discrimination in the last 12 months (18.5%-23.7%). Finally, concerning sex work, the proportion was found to be 13.7% (61 MSM) in Medellín, 15.8% (69 MSM) in Bogotá, and 27.5% (114 MSM) in Cali (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage

Distribution of Sociodemographic, Substance Use, and Personal Characteristics

of Men Who Have Sex with Men

Figure 1.

Percentage

Distribution of Sociodemographic, Substance Use, and Personal Characteristics

of Men Who Have Sex with Men

Sociodemographic Characteristics of MSM Engaged in Sex Work

In Medellín, sex workers were primarily under the age of 24 and belonged to low-middle socioeconomic strata. The majority (95.2%) had completed at least secondary education. About 37.7% had no income, and 67.1% were working at the time of the study. The consumption of poppers (42.6%) and marijuana (55.7%) was high. 21.3% reported a recent STI, and 22.9% were confirmed to be HIV-positive. Discrimination based on sexual orientation was reported by 27.8%.

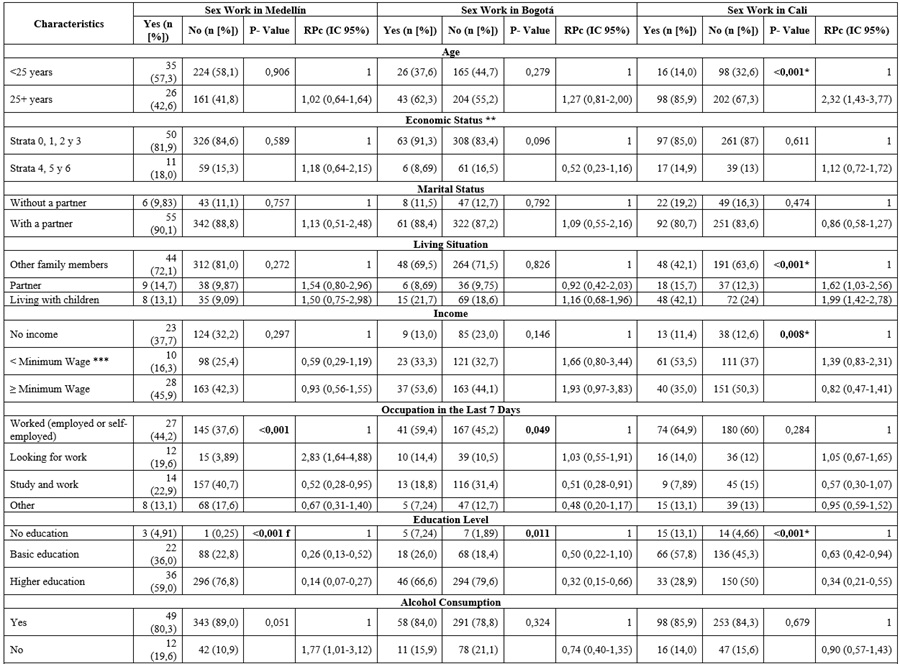

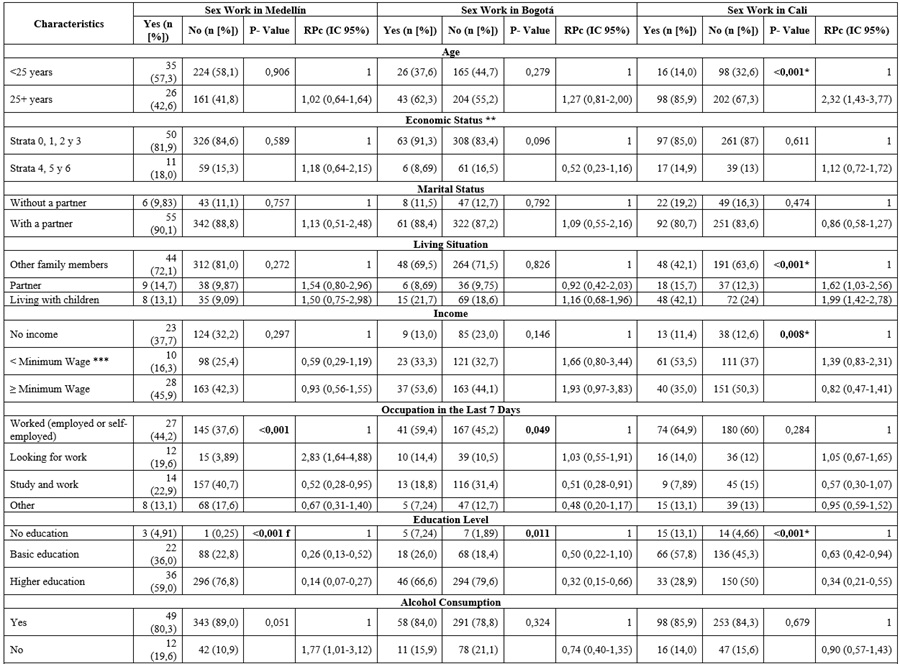

In the bivariate analysis, significant associations were found between sex work and the following variables: occupation (p < 0.001), educational level (p < 0.001), marijuana consumption (p = 0.023), cocaine consumption (p = 0.004), Viagra consumption (p = 0.009), STIs (p = 0.022), and positive HIV results (p = 0.010). For example, seeking employment was associated with a prevalence ratio (PR) of 2.83 (95% CI: 1.64-4.88), while not consuming illicit substances was associated with a PR of 0.44 (95% CI: 0.26-0.76), indicating lower prevalence of sex work among those who do not consume these substances (Table 1).

In Bogotá, MSM were predominantly over 25 years old and from low socioeconomic strata. 92.3% had at least completed secondary education. 13.7% had no income, and 78.2% were employed. The consumption of marijuana (53.6%), cocaine (26%), and alcohol (84%) was frequent. 33.3% reported an STI in the last year, and 49.2% were HIV-positive. 31.8% reported experiencing discrimination. Significant associations were found with educational level (p = 0.011), occupation (p = 0.049), marijuana consumption (p = 0.002), cocaine consumption (p < 0.001), STIs (p < 0.001), and HIV status (p < 0.001). Higher education was associated with a lower likelihood of engaging in sex work (PR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.15-0.66), while living with HIV was associated with a higher prevalence (PR = 2.08; 95% CI: 1.42-3.04) (Table 1).

In Cali, the majority of sex workers were over 25 years old (85.9%) and from low socioeconomic strata (0-3). 11.4% had no income, 78% were working, and 34.2% consumed cocaine. 29.8% were confirmed to be HIV-positive, and 65% reported high vulnerability to HIV. Significant associations were observed between sex work and the following variables: age (p < 0.001), household composition (p < 0.001), educational level (p < 0.001), marijuana consumption (p < 0.001), cocaine consumption (p < 0.001), popper use (p = 0.003), Viagra consumption (p = 0.02), and HIV vulnerability (p = 0.01). Being over 25 years old was associated with a PR of 2.32 (95% CI: 1.43-3.77), while not consuming illicit substances was associated with a PR of 0.45 (95% CI: 0.33-0.62), reflecting an inverse relationship between substance use and sex work (Table 1).

It is important to note that in all three cities, seeking employment, not having an education, having no income, consuming illicit substances, having an STI, living with HIV, and being vulnerable to HIV all increased the likelihood of being a sex worker (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sexual Work Behavior by

Each Study City According to Sociodemographic, Substance Use, and Personal

Factors of Men Who Have Sex with Men and Are Sex Workers

* Variables that are significant are included in the final model if their p-value is less than 0.05 or if their confidence interval does not cross 1.

** Strata 0, 1, 2, and 3: low-middle; strata 4, 5, and 6: high.

*** Legal minimum wage (SMLV) equivalent to USD 335.

**** The p-value was calculated using the chi-square test of independence; Fisher’s exact test (f) was used for values <5.

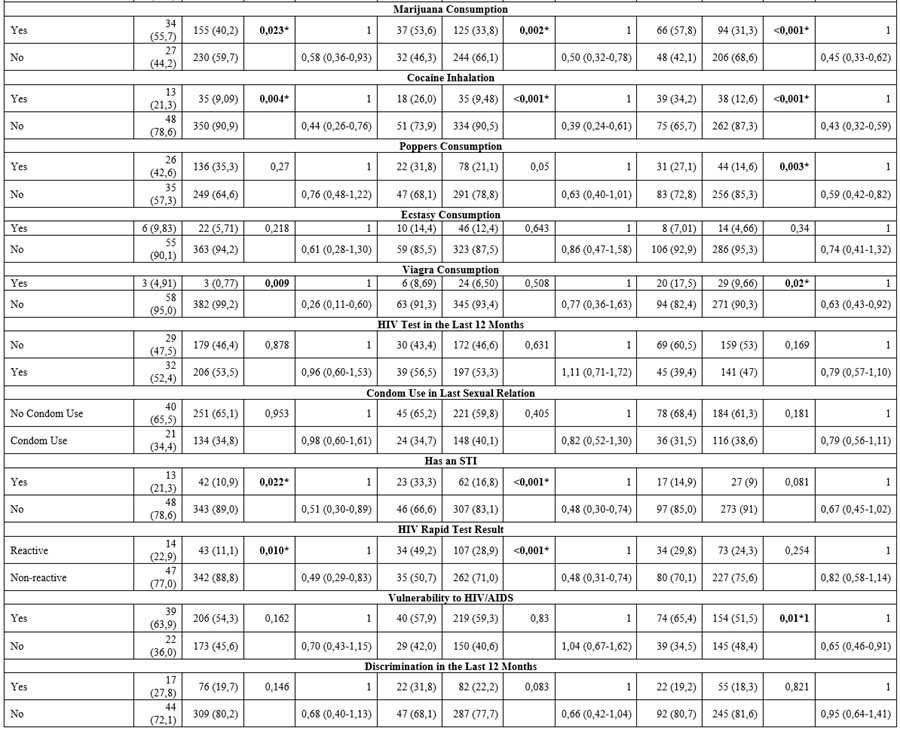

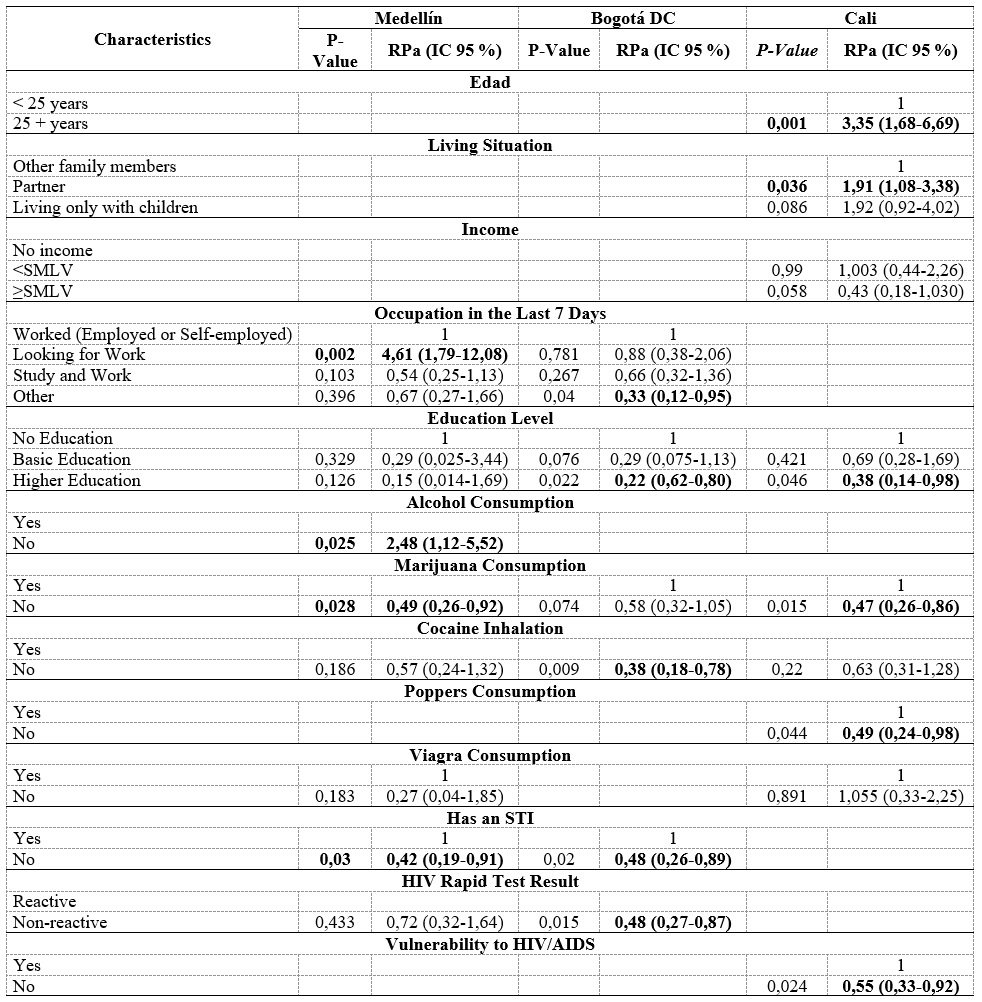

Main Challenges Facing Sex Work

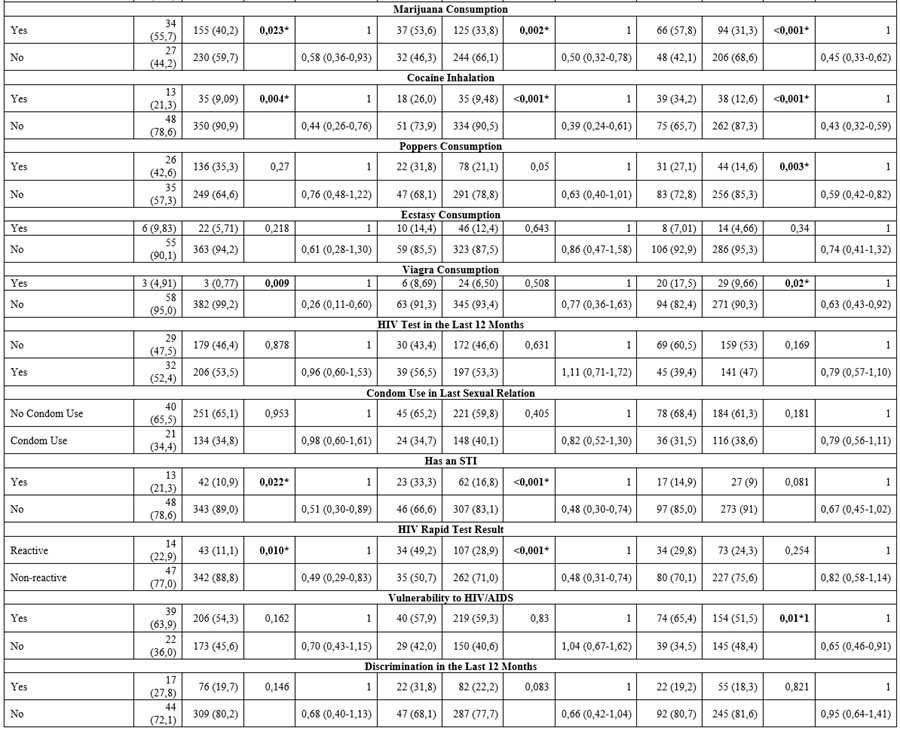

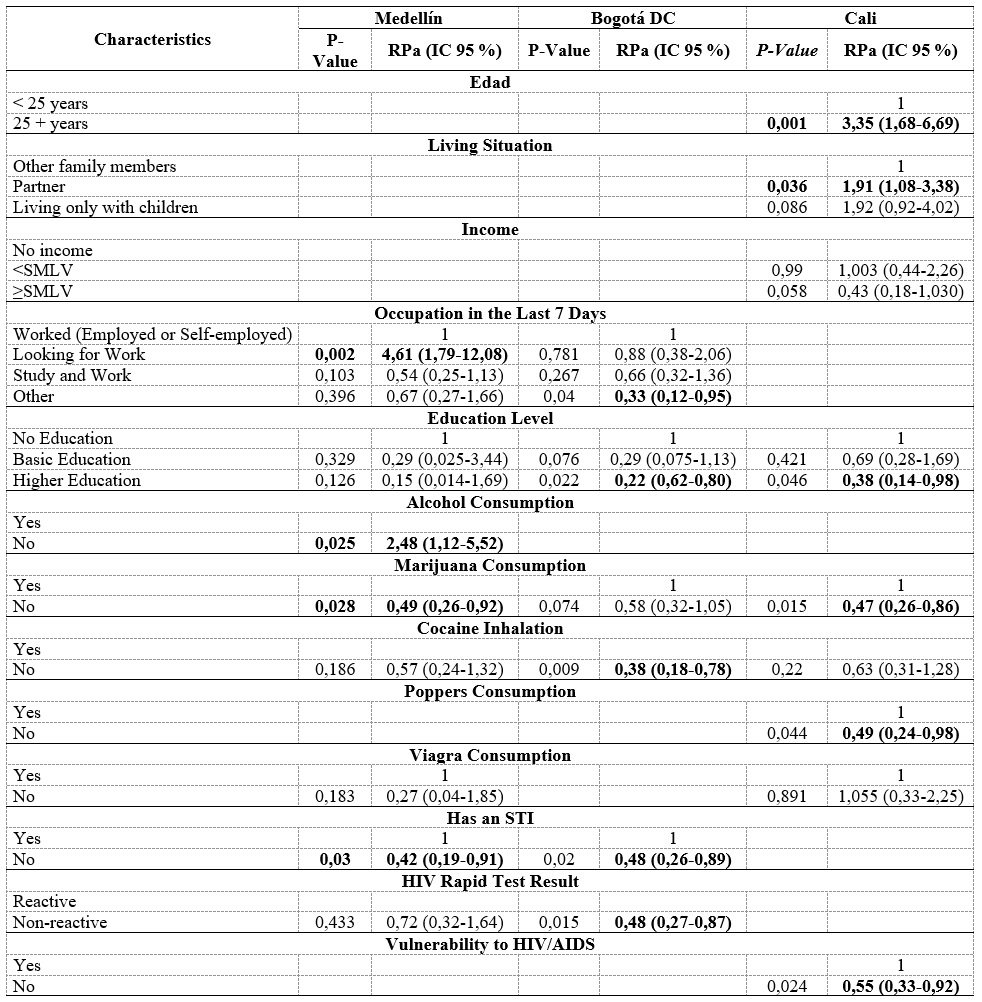

After adjusting for each of the variables that were significant in the bivariate analysis, the following findings were made for each city:

-

Medellín:

Seeking employment (RPa = 4.61; 95% CI: 1.79-12.08),

marijuana consumption (RPa = 0.49; 95% CI:

0.26-0.92), and a diagnosis of an STI (RPa = 0.42;

95% CI: 0.19-0.91) were the variables with the highest weight.

-

Bogotá:

Having higher education (RPa = 0.22; 95% CI:

0.62-0.80) and not consuming cocaine (RPa = 0.38; 95%

CI: 0.18-0.78) were associated with a lower prevalence of sex work.

-

Cali:

Being older than 25 years (RPa = 3.35; 95% CI:

1.68-6.69), living with a partner (RPa = 1.91; 95%

CI: 1.08-3.38), and having a high perception of vulnerability to HIV (RPa = 0.55; 95% CI: 0.33-0.92) showed significant

associations.

Payment for sexual relations in all three cities was associated with seeking employment, lack of formal education, low income, substance use, the presence of STIs or HIV, and perceived vulnerability to HIV/AIDS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Explanatory Model of Sociodemographic, Substance Use, and Personal Factors of

Men Who Have Sex with Men and Are Sex Workers in Three Cities in Colombia.

* The variables included in the model were those that were significant in the bivariate analysis, with a p-value less than 0.05 or whose confidence interval did not include 1.

Discussion

This study identifies that the factors associated with payment for sexual relations in all three cities were, in general, seeking employment, lack of education, lack of income, illicit substance use, presence of an STI, living with HIV, and having a degree of vulnerability to HIV. These factors were found to increase the likelihood of receiving money in exchange for sexual relations.

Similarly, the study found an overall proportion of sex work ranging from 13.7% to 27.5%. These values are similar to those found in China in 2018 (7.5%), Thailand in 2014 (15%) (23), India in 2017 (20%), South Africa in 2016 (25%), Canada in 2014 (13.6%), the United States in 2015 (11.5%) (24), Mexico in 2017 (9.8%) (25), Peru in 2012 (17.4%), and Brazil in 2015 (21.5%) (26). It is important to note that all the studies mentioned used the same methodology. Additionally, it should be understood that sex work is not an isolated or marginal phenomenon but rather a common and transversal reality across diverse cultures and contexts.

Moreover, several studies have found that MSM who engage in sex work face a higher risk of HIV and other STIs due to the nature of their work and the increased frequency of sexual contacts. In this study, HIV prevalence among MSM ranged from 33.3% to 50%. While this is expected, it is concerning that this is one of the highest reported prevalences when compared to other studies, such as the one conducted in the United States in 2017 (14.7%) (27), in Mexico in 2017 (18.5% on average) (28), in Thailand in 2016 (21.7%) (29), in Brazil in 2015 (13.2%) (30), in Peru in 2014 (24.5%) (31), and in the Dominican Republic in 2012 (14.3%) (32). Studies have also found a high prevalence of substance use among MSM sex workers, including alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine, and designer drugs. This finding is consistent with recent research in Latin America (17,33).

Stigma and discrimination are factors that may contribute to the prevalence of sex work among MSM, particularly in countries where homosexuality is illegal or socially stigmatized. These factors also limit access to employment and healthcare services, influencing MSM’s decision to resort to sex work as a means of livelihood. A study conducted in Peru in 2012 found that MSM who had exchanged sex for money or goods in the past year reported more lack of access to healthcare, less social support, and higher levels of violence compared to MSM who did not engage in sex work (34).

A study conducted in Brazil in 2015 found that MSM who

had exchanged sex for money or goods in the last year were more likely to

report a lack of formal education, lack of employment, and increased experience

of violence compared to MSM who did not report engaging in sex work (34). While

this study shows that discrimination tends to increase sex work, no statistical

differences were found to confirm this situation. However, the results found

should not be disregarded. Efforts must continue to reduce discrimination,

emphasizing access to healthcare services, reducing substance use, and raising

awareness and education for families, communities, and governmental entities.

Conclusion

This study reveals that multiple factors, such as lack of employment, education, income, and illicit substance use, are associated with MSM’s participation in sex work in three Colombian cities. The prevalence of sex work among MSM is comparable to that of other countries, and the high prevalence of HIV, ranging from 33.3% to 50%, is particularly concerning and higher than reported in other international studies. This cannot be understood solely from an individual or moral perspective, but rather as the result of specific social and economic contexts that require comprehensive, differentiated interventions centered on the social determinants of health.

Stigma and discrimination continue to be significant barriers that exacerbate the vulnerability of MSM engaged in sex work. Although no statistical differences were found to confirm a direct relationship between discrimination and sex work, the evidence suggests that continued efforts are necessary to reduce these barriers. It is recommended to prioritize access to healthcare services, reduce substance use, and promote awareness and education within families, communities, and governmental entities to provide comprehensive support to this population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants, CES

University, and EnTerritorio, as funding entities for

the research.

References

1. Jacques Aviñó C, Andrés A de, Roldán L, Fernández Quevedo M, García de Olalla P, Díez E, et al. Trabajadores sexuales masculinos: entre el sexo seguro y el riesgo. Etnografía en una sauna gay de Barcelona, España. Cien Saude Colet. 2019 Dec;24(12):4707-16. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-812320182412.27842017

2. Mantecón A, Juan M, Calafat A, Becoña E, Román E. Respondent-Driven Sampling: un nuevo método de muestreo para el estudio de poblaciones visibles y ocultas. Adicciones. 2008;20(2):161-70. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.280

3. Kimmel M. Homofobia, temor, vergüenza y silencio en la identidad masculina. Bibl Virtual Ciencias Soc [internet]. 2014 Jun;6(2):103. Disponible en: http://www.caladona.org/grups/uploads/2008/01/homofobia-temor-verguenza-y-silencio-en-la-identidad-masculina-michael-s-kimmel.pdf

4. Villa Camarma E. Estudio antropológico en torno a la prostitución. Cuicuilco [internet]. 2010 [citado 2024 feb 7];17(49):157-79. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0185-16592010000200009&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es

5. Agustín L. Sex at the margins: migration, labour markets and the rescue industry. London: Zed Books; 2007. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350222496

6. Morales-Mesa SA, Arboleda-Álvarez OL, Segura-Cardona ÁM. Las prácticas sexuales de riesgo al VIH en población universitaria. Rev Salud Pública. 2014;16(1):27-39. https://doi.org/10.15446/rsap.v16n1.30659

7. Ramos Brum V. XX: técnicas grupales para el trabajo en sexualidad con adolescentes y jóvenes. Promoción y educación para la salud [internet]. Montevideo: Programa Global de Aseguramiento de Insumos para la Salud Reproductiva (UNFPA). Tendencias innovadoras. 2011. 84 .. Disponible en: https://redmapa.org/2021/12/20/xx-tecnicas-grupales-para-el-trabajo-en-sexualidad-con-adolescentes-y-jovenes/

8. Naciones Unidas. Orientación sexual e identidad de género en el derecho internacional de los derechos humanos [internet]. 2015. Disponible en: https://acnudh.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/orentación-sexual-e-identidad-de-género2.pdf

9. TAMPEP International Foundation. Sex work in Europe: a mapping of the prostitution scene in 25 European countries [internet]. 2009 [citado 2024 feb 7];79. Disponible en: https://tampep.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/TAMPEP-2009-European-Mapping-Report.pdf

10. Kloek M, Bulstra CA, van Noord L, Al‐Hassany L, Cowan FM, Hontelez JAC. HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men, transgender women and cisgender male sex workers in sub‐Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2022 Nov 23;25(11). https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.26022

11. Harris MTH, Shannon K, Krüsi A, Zhou H, Goldenberg SM. Social-structural barriers to primary care among sex workers: findings from a community-based cohort in Vancouver, Canada (2014-2021). BMC Health Serv Res. 2025 Jan 24;25(1):134. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-025-12275-x

12. Giacomozzi AI, da Silva Bousfield AB, Pires Coltro B, Xavier M. Representaciones sociales del vivir con el VIH/SIDA y vivencias de prejuicios en Brasil. Lib Rev Peru Psicol. 2019 Jun 27;25(1):85-98. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2019.v25n1.07

13. Council of Europe Publishing. Discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity in Europe 2nd edition Human Rights Report [internet]. 2011 [citado 2023 feb 19]. Disponible en: https://rm.coe.int/discrimination-on-grounds-of-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-in/16809079e2

14. Beyrer C, Baral SD, van Griensven F, Goodreau SM, Chariyalertsak S, Wirtz AL, et al. Global epidemiology of HIV infection in men who have sex with men. Lancet. 2012 Jul;380(9839):367-77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60821-6

15. Cortés Alfaro A, García Roche R, Fullerat Alfonso R, Fuentes Abreu J. Instrumento de trabajo para el estudio de las enfermedades de transmisión sexual y VIH/SIDA en adolescentes. Rev Cuba Med Trop [internet]. 2000;52(1):48-54. Disponible en: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0375-07602000000100009

16. Montoya SJ. Enfrentando el estigma y las discriminación por VIH desde el trabajo social [trabajo de grado en internet]. Navarra: Universidad de Navarra; 2016. Disponible en: https://academica-e.unavarra.es/bitstream/handle/2454/21491/TFG16-TS-MONTOYA-78613.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

17. Dourado I, Guimarães MDC, Damacena GN, Magno L, de Souza Júnior PRB, Szwarcwald CL. Sex work stigma and non-disclosure to health care providers: data from a large RDS study among FSW in Brazil. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019 Dec 5;19(1):8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-019-0193-7

18. Khan MR, Epperson MW, Mateu-Gelabert P, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Friedman SR. Incarceration, sex With an STI- or HIV-infected partner, and infection with an STI or HIV in Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY: a social network perspective. Am J Public Health. 2011 Jun;101(6):1110-7. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.184721

19. Berbesi Fernández DY, Segura Cardona AM, Molina Estrada AP, Martínez Rocha A, Ramos Jaraba S, Bedoya Mejia S. Comportamiento sexual y prevalencia de VIH en hombres que tienees relaciones sexuales con hombres en tres ciudades de Colombia [internet]. Medellín: Editorial CES. 2019. Disponible en: https://editorial.ces.edu.co/libros/comportamiento-sexual-y-prevalencia-de-vih-en-hombres-que-tienen-relaciones-sexuales-con-hombres-en-tres-ciudades-de-colombia/

20. Salganik MJ, Heckathornt DD. Sampling and estimation in respondent-driven sampling. Soc Method. 2004;34(1):193-239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00152.x

21. Amon J, Brown T, Hogle J, MacNeil J, Magnani R, Mills S, et al. Behavioral surveillance surveys (BSS): guidelines for repeated behavioral surveys in populations at risk of HIV https://doi.org/.Arlington: Family Health International; 2000. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/hiv/strategic/en/bss_fhi2000.pdf

22. Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos. Resolución 8430 del 4 de Octubre de 1993.

23. Grulich AE, de Visser RO, Smith AMA, Rissel CE, Richters J. Sex in Australia: homosexual experience and recent homosexual encounters. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003 Apr;27(2):155-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2003.tb00803.x

24. Hernández-Romieu AC, Sullivan PS, Rothenberg R, Grey J, Luisi N, Kelley CF, et al. Heterogeneity of HIV prevalence among the sexual networks of black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta. Sex Transm Dis. 2015 Sep;42(9):505-12. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000332

25. Miller WM, Buckingham L, Sánchez-Domínguez MS, Morales-Miranda S, Paz-Bailey G. Systematic review of HIV prevalence studies among key populations in Latin America and the Caribbean. Salud Publica Mex [internet]. 2013 [citado 2023 abr 4];55:S65-78. Disponible en: http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0036-36342013000300010&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=en

26. Gruskin S, Tarantola D. Universal Access to HIV prevention, treatment and care: assessing the inclusion of human rights in international and national strategic plans. AIDS. 2008 Aug;22(Suppl 2):S123-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000327444.51408.21

27. Reisner SL, Mimiaga MJ, Bland S, Driscoll MA, Cranston K. Characteristics of transgender women living with HIV receiving medical care in the United States. LGBT Heal. 2017;4:314-8. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2014.0099

28. Patterson TL, Strathdee SA, Semple SJ, Chavarin CV, Abramovitz D, Gaines TL et al. Prevalence of HIV/STIs and correlates with municipal characteristics among female sex workers in 13 Mexican cities. Salud pública Méx [revista en la Internet]. 2019 Abr [citado 2025 Oct 04]; 61( 2 ): 116-124. https://doi.org/10.21149/8863

29. Crowell TA, Nitayaphan S, Sirisopana N, Wansom T, Kitsiripornchai S, Francisco L, et al. Factors associated with testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men and transgender women in Bangkok, Thailand. AIDS Res Ther. 2022 Jun 21;19(1):25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-022-00449-0

30. Grinsztejn B, Jalil EM, Monteiro L, Velasque L, Moreira RI, García AC, et al. Unveiling of HIV dynamics among transgender women: a respondent-driven sampling study in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Lancet HIV. 2017;4(4):e169-e176. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30015-2

31. Cáceres CF, Mendoza W, Konda K, Lescano A. Nuevas evidencias para las políticas y programas de salud en VIH/sida e infecciones de transmisión sexual en el Perú. Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica [internet]. 2014;31:305-15. Disponible en: https://www.iessdeh.org/BAMAKO/books/Nuevas%20Evidencias%20en%20VIH %20- %20Peru %20- %20Caceres %20et %20al %20- %20Feb %202007.pdf

32. Amesty S, Pérez-Figueroa R, Stonbraker S, Halpern M, Donastorg Y, Pérez-Mencia M, et al. High burden of sexually transmitted infections among under-resourced populations in the Dominican Republic. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2023;10. https://doi.org/10.1177/20499361231193561

33. Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A, Nieves-Rosa L, Dı́az F. Substance use and sexual risk behavior: understanding their association among four ethnic groups of Latino men who have sex with men. J Subst Abuse [internet]. 2000 Dec;11(4):323-36. Disponible en: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0899328900000304

34. Reisner SL, Silva-Santisteban A, Huerta L, Konda K, Pérez-Brumer A. Gender-responsive HIV prevention and care research with transgender communities: lessons learned from Peru. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025 Jul 10;49:101182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2025.101182

Notes

Conflict of Interest

All

authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

We thank CES University and EnTerritorio

for their financial support.

Author notes

a Correspondence

author: sebedoya@ces.edu.co

Additional information

How to cite: Bedoya-Mejía S, Cardona Zapata KD,

Ramos-Jaraba S, Contreras Martínez HJ, Berbesí-Fernández DY. Paid Sex among

Men Who Have Sex with Men: A Comparative Analysis in Three Colombian Cities. Univ Med. 2025;66. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.umed66.psam