Sexual violence comprehends any sexual act (or attempt to obtain it) directed at another person and that occurs against the victim’s will, regardless of the relationship between the people involved. It groups a variety of events, such as sexual harassment, stalking, incest and rape (Government of Newfoundland and Labrador - Canada, 2014; Lee & Jordan, 2014).

Although all forms of sexual violence have serious implications over the victim’s life, rape is considered one of the most serious. It refers to the act of forcing another person, usually a woman, to have sexual intercourse in the absence of freely given consent (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010).

Despite the underreporting, data from 2022 (Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública [FBSP], 2023) indicate that, only in Brazil, 33.4 % of women aged 16 years or over have experienced some form of violence (physical and/or sexual) by a current or former partner, spouse, or boyfriend. A result that overcomes the world average, estimated at 27 % according to the Global Prevalence Estimates of Intimate Partner Violence (WHO, 2021).

It is also estimated that 43 % of Brazilian women have also suffered from different forms of violence (physical, psychological, and sexual) inflicted by an intimate partner throughout their lives, equivalent to 27.6 million women aged 16 years or older. Out of them, 21.1 % (13.6 million) declared an experience of being forced to have sex against their will (FBSP, 2023).

Although men can also fall victim to these forms of violence – including sexual violence (i.e., about 1 in 26 men have experienced completed or attempted rape and approximately 1 in 9 men were made to penetrate someone during his lifetime) women are still the main victims of this type of crime in the country (Basile et al., 2014; Cerqueira & Coelho, 2014). This is also true for the rest of the world (Planty et al., 2013; Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, n.d.a; n.d.b), reflecting the particularities of this form of violence (Chapleau & Oswald, 2010; Scarpati, 2018).

Hayes et al. (2013), for example, argue that the intrinsically social gender component represents one of the biggest barriers to rape prevention. According to these authors, rape is not a result of an individual pathology, but the product of individual tendencies combined with different sociocultural elements. As discussed by Scarpati (2013; 2018), Brazilian society still admits a conservative view of men and women’s social roles, thus contributing to a scenario in which the power imbalance between men and women either directly or indirectly legitimizes the perpetration of violence against this minority (Scarpati & Pina, 2017).

Another element that seems to be related to the perpetration of this form of violence is known as the ‘rape myth’. Rape myths are distorted, stereotyped and/or false beliefs about rape, rape victims and aggressors (Eyssel et al., 2006; Süssenbach et al., 2013) and can be explained according to their three main functions: a) blaming the victim; b) removing the perpetrator’s responsibility for the act; and c) denying the existence of violence (Bohner et al., 2010; Smith & Skinner, 2017). Concerning the victim, those myths suggest that the woman could be a) lying about the violence; b) “asking” for it; or c) pretending that she was raped because she changed her mind after having consensual sex with someone. Additionally, some of the myths related to the victim suggest that there is a “typical” victim and as a result, some women, such as prostitutes, do not fit into the stereotypical ‘true victim group’ (Scarpati, 2018; Temkin et al., 2018).

Concerning the offender, on the other hand, these myths purport that the perpetrator: a) did not intend to hurt the woman; and/or b) should not be blamed since men struggle to control their sexual instincts. In addition, and similarly to what occurs in relation to the victim, rape myths also perpetuate the idea that, c) there is a ‘typical offender’ profile (with specific characteristics) (Bohner et al., 2010). Those myths also serve as neutralizers, thus allowing offenders to find a justification for their behavior, disengaging them from any social norm that could make them feel guilty or ashamed (Scarpati, 2018; Temkin et al., 2018).

In respect to violence itself, some of the myths contribute to perpetuate the idea that rape is trivial and not a serious offence while women supposedly tend to overvalue its consequences on their lives. For some authors, rape myths can be understood as a form of moral disengagement strategy (Franiuk et al., 2008; Page & Pina, 2015; Page et al., 2016; Scarpati, 2018), or as a special, providential form of justice, considering those myths are related to the idea that ‘good things happen to good people’ and ‘bad things happen to bad people’. In other words, when facing a case of sexual violence, people (either the victim or the general population) tend to rely on those beliefs to justify violence and, at the very least, be able to face events with a sense of predictability and control. As pointed out by some authors, one of the most remarkable characteristics of this phenomenon is the fact that sexual violence seems to be the only form of violence where the victims tend to be blamed for the offence they have suffered, instead of being supported by the society and authorities (Coulouris, 2010; Eyssel & Bohner, 2011; Fakunmoju, 2022).

Beyond victims and offenders, one group directly involved with this form of violence is justice system workers. Lawyers, prosecutors, judges, and even the jury. All of them play an important role in the way cases of sexual violence are understood and judged, affecting not only the victim’s life but also their family’s and the offender’s, and, to some degree, the legislation itself.

In cases of rape, for example, concepts such as the “honest woman” and traditional gender norms are often applied to disqualify victims, moving the responsibility away from the perpetrators (Porto & Costa, 2010; Smith & Skinner, 2017). In fact, authors such as Temkin et al. (2018) suggest that lawyers, judges, juries and prosecutors seem to have trouble dealing with sexual crimes and, not infrequently, these cases are ignored or dealt with according to sexist biases.

In Brazil, even as far as the 1990s, if the perpetrator married his victim, all charges would be dropped. According to Pandjiarjian (2006), at that time, the focus was not helping the woman, as a victim, to get justice, but rather the preservation of the victim’s and her family’s honor. This was due to the belief that if a woman’s reputation was affected, her chances to find a husband would be diminished and her family would be dishonored. In other words, despite the advent of the Brazilian Federal Constitution in 1988, with its principle of gender equality, some practices of the justice system would still disregard that principle (Pandjiarjian, 2006).

This form of treatment has long been allowing men and women to trivialize the seriousness of rape and its consequences on the victim’s life (Koepke et al., 2014). As suggested by Coulouris (2010) and Smith and Skinner (2017), despite the changes and the progress achieved in the legislation, the decisions by the Judiciary seem to be affected by individual’s understanding of this offence as well as their values, beliefs and prejudices. For example, even though according to the current Brazilian legislation (Presidência da República, August 7, 2009), rape is a gender-neutral crime, with both men and women being regarded as potential victims of this form of violence, few men come forward to report having been raped, and for most people only women can be considered rape victims. Thus, the investigation of a rape —its background and consequences— cannot be dissociated from the context in which it takes place (Scarpati, 2018).

Based on the above, next sections present two constructs: honor and human values. We believe they may contribute to the understanding of Law students’ attitudes towards rape, by considering their endorsement of rape myths. As discussed by Vandello et al. (2008), these can serve as tools for better comprehending how the distorted beliefs that underpin discourses and decisions have been affecting the practices of the legal system.

Honor Concerns

Pitt-Rivers (1973) defines honor as a link between society’s ideals and expectations, and the reproduction of these ideals by individuals through their aspiration to personify them. In other words, honor is someone’s value not only according to his/her own eyes, but also to society. It helps regulate people’s behavior, to the extent that it is related to one’s estimation of worth and self-pride (Gouveia et al., 2013; Oliveira, 2009). At the same time, it helps define groups’ identities since it is also dependent on being acknowledged by the group, i.e., having one’s worth and self-pride recognized, in a shared code where this claim is negotiated (Guerra, Giner-Sorolla & Visíljevic, 2013).

However, Ramos (2012) and Souza (2010) stress that the usefulness of the notion of honor is not a consensus between researchers. According to them, it is not difficult to see a division between authors who consider it an outdated concept and those who view it as a very useful tool for the comprehension of varied social phenomena (Oliveira, 2009; Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002). To Rodriguez Mosquera et al. (2002), for example, honor remains an important concept in many contemporary cultures and must be considered by authors who aim to understand how different cultures deal with problems such as the perpetration of violence against women. In this sense, honor is a complex system of norms, values and practices that relate to people’s attitudes towards different aspects of their lives, and can be organized into four codes: family, social, feminine, and masculine honor (Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002).

The first code, family honor, is based on the reputation of the family in a society. This reputation is directly linked to each individual family member’s behavior. Therefore, if a family member is considered ‘dishonorable,’ the whole family will be affected. The second code, social honor (or integrity), is based on notions such as trust, honesty and reputation, and is considered the most universal type of honor. In this code, the emphasis is on the maintenance of someone’s personal integrity as well as his/her reputation in any interpersonal relationship (Guerra, Gouveia, Araújo, Andrade & Gaudêncio, 2013; Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002).

The third and fourth dimensions deal respectively with the masculine and feminine codes of honor, referring to its gender-related aspects (Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002). Masculine honor, for example, expresses a direct association between a male’s reputation and his capacity to act as a ‘real man’ (Scarpati, 2018). This can be demonstrated either through his sexual behavior (i.e. virility), by having a prominent position in the labor market, or through the effort to keep his authority within the family. In other words, it is based on the idea that men need to be sexually daring, strong, and act as providers and protectors of their families. It is important to note, however, that despite the fact that masculine honor emphasizes the assumption of male superiority, and consequently reinforces the disparity between genders, women also perpetuate the ideals of masculinity purported by this code (Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002).

Feminine honor is also influenced by traditional gender norms. However, in this case the premise is that a woman’s sexual activity must be controlled in order to preserve her (and her family’s) reputation (Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002; Scarpati, 2013). In other words, there is an association with ideals of chastity and purity, and women are expected to be modest and (sexually) restrained.

Generally speaking, honor can provide a backdrop for understanding how people see themselves and relate to others in different societies. Similarly to honor, human values are another variable that can be useful for the understanding of people’s behavior in society and, here, their understanding of cases of violence.

Human Values

Human values are a key element of an individual’s cognitive system. They provide a framework for people to explain their opinions, beliefs, attitudes and behaviors (Rokeach, 1973). Human values do not relate to specific objects; rather, they refer to ideas, situations and institutions stemming from each individual’s socialization experiences (Cieciuch & Schwartz, 2017). They can be defined as guides to individual and group actions and expressions of one’s needs (Gouveia et al., 2014).

People do not differ in terms of which specific values they hold, but in terms of the priorities they give to each set of values. These priorities are related to the socio-cultural context in which they are inserted (Gouveia et al., 2013), and can, therefore, be an important tool for understanding people’s preferences and decisions in regard to different phenomena.

According to Gouveia et al. (2014), values have two main functions: the first one—the Guidance Function, forming the horizontal axis—represents the structure and type of orientation (social, personal or central), whereas the second—Type of Motivation, forming the vertical axis—expresses the function of values that give meaning to human needs (materialistic or humanitarian values) (Gouveia et al., 2013; 2014). The combination of these two axes originates six specific sub-functions:

-

Promotion (personal guidance, materialistic motivation): values that emphasize achievements of material nature, as well as practical decisions and behaviors. Also related to the need to be powerful, efficient, and to the desire of achieving goals. Values: Power, Prestige, and Success.

-

Excitement (personal guidance, humanitarian motivation): values that favor change and innovation in the structure of social organizations, as well as the need for different forms of personal satisfaction (e.g., sex). Values: Emotion, Pleasure, and Sexuality.

-

Existence (central guidance; materialistic motivation): values that express individuals’ concern for ensuring basic living conditions (psychological and biological) as well as for maintaining a well-planned and organized life. Values: Health, Stability, and Survival.

-

Suprapersonal (central guidance; humanitarian motivation): This sub-function emphasizes people’s need for information, for being seen as autonomous individuals, for self-development, and for appreciating and understanding the world. Values: Beauty, Knowledge, and Maturity.

-

Interactive (social orientation, humanitarian motivation): This sub-function is related to values addressing the needs of individuals to feel beloved, safe, and to establish and maintain satisfactory interpersonal relationships. Values: Affectivity, Belonging, and Support.

-

Normative (social orientation, materialistic motivation): This sub-function groups values that emphasize the idea of a social life based on respect for symbols, traditions and cultural standards. People who value this function tend to behave according to their in-group standards. Values: Obedience, Religiosity, and Tradition.

Human values are principles that each individual considers important in life and that, in a close relationship to the environment, guide their behavior in the world (Miller, 2014). One can observe, for example, that individuals who agree with values related to the ideas of universalism, equality and transcendence are inclined to disagree with discriminatory views and practices (Belo et al., 2005). Thus, the importance of recognizing and understanding the beliefs that underpin individuals’ discourse and guide their behaviors becomes evident; specially when one considers that some groups (e.g., Law students) will eventually be working (either directly or indirectly) with victims and offenders in cases of sexual violence.

It is worth noting, however, that to the extent of the authors’ knowledge no work has previously attempted to explore how the importance given to human values and honor concerns affects individuals’ endorsement of rape myths as well as the potential effects of rape myths on future legal practices in Brazil. Therefore, the relevance of this study is that its results will not only: a) encourage discussion, even at the undergraduate level, on the subject; b) properly prepare these future professionals to enter into contact with victims and perpetrators; c) contribute to rethinking established strategies; but also promote the d) understanding of how superior education has been contributing—or not—to an ethical and humanitarian worldview.

Method

Participants

Participants were 281 students in the last year of Law school, from public (8.2 %) and private (91.8 %) universities in the Brazilian Southeast region. Women constituted 57.6 % of the sample, and the age of the respondents ranged from 20 to 46 years (M = 23.6, SD = 3.78). Most of the respondents were Catholic (52.7 %), had a moderate level of religiosity (M = 3.09, SD = 1.25), and were single (89.5 %). The sample was non-probabilistic and intentional, as only participants who were willing to collaborate when consulted by researchers were considered.

Instruments

Participants answered a questionnaire formed by the following instruments.

Socio-demographic questions: all participants were asked to answer questions about age, gender, marital status, religion, and type of university. Level of religiosity was also measured by a question asking, “Do you consider yourself a religious person?”, answered by a 5-point Likert scale ranging from no religious (1) to completely religious (5).

Honor-Scale (HS): developed in Spain by Rodriguez Mosquera et al. (2002). Its original formulation consists of 25 items divided into four subscales, namely: family honor (e.g., Being unable to defend one’s family’s reputation), personal integrity (e.g., Not keeping up one’s word), masculine-typed honor (e.g., Not defending one-self when others insult you) and feminine-typed honor (e.g., Being known as someone it is easy to sleep with). Participants must answer how much each of these items would make them feel bad, on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not at all bad) to 9 (very badly). The Brazilian Portuguese version used in this study was validated by Guerra, Gouveia, Araújo, Andrade and Gaudêncio(2013); it consists of 16 items. In this study’s sample, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.61 (masculine honor) to 0.85 (feminine honor).

Illinois Rape Myths Acceptance Scale (IRMA): developed by Payne et al. (1999); consists of 45 items. The Brazilian Portuguese version was validated by Scarpati et al. (2014), consisting of 34 items subdivided into four subcategories. Each of these categories address different aspects of the acceptance of rape myths: It is her fault (e.g., If a woman is raped while drunk, she bears some responsibility for letting things get out of control); It is not “too serious” (e.g., Rape is not as big a problem as some feminists want people to believe); It is just an excuse (e.g., While most women do not admit this, they often find that being forced to have sex is exciting); It is not his fault/male instinct (e.g., Men usually have no intention of forcing women to have sex, but sometimes they are driven by overwhelming sexual urges). Respondents should indicate how much they agree or disagree with each statement on a five-point scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = agree. In this sample, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranged from 0.64 (It is not his fault/male instinct) to 0.74 (It is her fault).

Basic Human Values Questionnaire. This questionnaire was based on Gouveia’s (Gouveia et al., 2014) theoretical model and consists of 18 items expressing basic human values. It is subdivided into six subcategories: existence (e.g., Health: worrying about your health to avoid becoming ill; not being sick), suprapersonal (e.g., Maturity: feeling able to achieve life goals, and to develop your capabilities), normative (e.g., Tradition: following the social norms of your country; respecting the traditions of the society you live in), interactive (e.g., Social support: getting help when you need it; feeling you are not alone in the world), promotion (e.g., Success: getting what you aim for; being efficient in everything you do) and excitement (e.g., Sexuality: having sex; getting sexual pleasure). Each participant would indicate—based on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (totally unimportant) to 7 (totally important)—the degree of importance of each value in their lives. In this study’s sample, the scale showed a 0.70 level of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha).

Procedure

After approval from the Ethics Committee (Approval number 312/11), researchers contacted different higher education institutions and explained the research’s objectives. After receiving permission, a researcher and a few trained assistants administered the questionnaire in a collective classroom environment. Participants were informed of the objectives, the voluntary nature of the survey and the confidentiality of participants’ personal data; all were asked to sign an informed consent form, in which all relevant information regarding the research was explained. The questionnaire was answered individually by each of the participants and kept in an envelope.

Results

In order to understand the effects of honor and human values on individuals’ endorsement of rape myths, four analyzes of hierarchical multiple regression were conducted (via the stepwise method). Each dimension of rape myths was included as a dependent variable. Independent variables were participants’ gender (Block 1), values’ subfunctions and honor concerns (Block 2). Tables 1 and 2 present results of variables that significantly explained the different dimensions of rape myths in this population.

The dimension It is her fault was positively explained by normative values. Additionally, it was negatively explained by suprapersonal values and participant’s gender, indicating that male participants showed higher levels of agreement with this dimension. These IVs, together, explained 8 % of the variance in this dimension. These results suggest that individuals who tend to agree with the idea that women are, somehow, responsible for their victimization also tend to endorse values of obedience, tradition, and religiosity as guiding principles in their lives. Participants who guide their lives based on suprapersonal values (e.g., social justice, maturity and knowledge), in turn, tend to disagree with this notion.

Table 1.

Predictors of Dimensions 01 – ‘It is her fault’ and 02 – ‘It is not too serious’

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

The dimension It is not “too serious” refers to the notion that women tend to exaggerate when talking about the consequences of being a victim of sexual violence. Similarly to what occurred in the first dimension, this dimension was also negatively explained by the importance given to suprapersonal values as well as the participant’s gender. It was also positively explained by masculine honor and, together, all independent variables explained 11 % of the outcome’s variance. These results suggest, again, that male participants showed a higher level of agreement with this dimension, and that participants who consider suprapersonal values as guides for their lives tend to disagree with this type of rape myth.

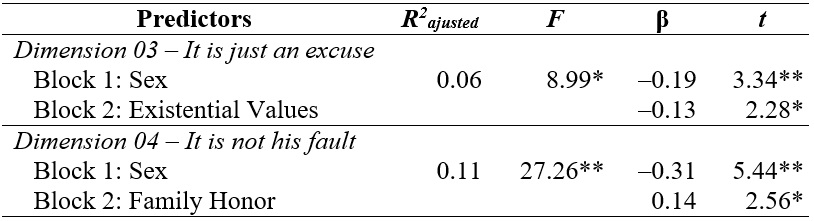

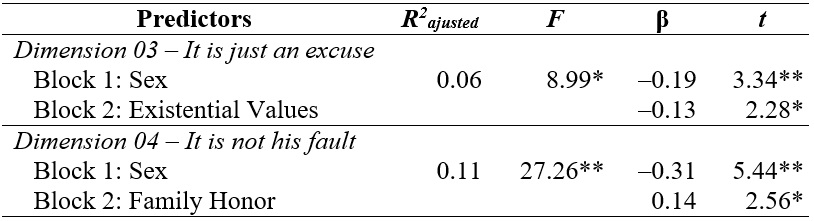

In relation to the third dimension, it is just an excuse (table 2), 6 % of the variance was negatively explained by the gender of the participant; suggesting, once again, that male participants endorse rape myths more frequently than women. This dimension was also negatively explained by existential values, suggesting that participants who attribute relevance to aspects such as survival, personal stability and health do not agree with the idea that women lie or exaggerate about the implications and consequences of sexual violence.

Table 2.

Predictors of Dimensions 03 – ‘It is just an excuse’ and 04 – ‘It is not his fault’

*p < 0.05

**p < 0.01

Finally, the fourth dimension (It is not his fault/male Instinct) had 11 % of its variance explained by the group of independent variables. Similarly to what occurred previously, this dimension was also explained by gender, suggesting that the male group had a higher level of agreement with the content of these myths. This dimension was also positively and statistically significantly explained by participants’ concerns with the preservation of family honor.

Discussion

This study aimed to comprehend the effects of honor concerns and the importance given to human values on Law students’ endorsement of rape myths. On this basis, it aimed to discuss the potential implications for their future professional practice. As previously stated, few authors have devoted themselves to this subject in Brazil, and a lot of work remains to be done regarding the understanding of the relationship between human values (Gouveia et al., 2014) and rape myths (Scarpati, 2013).

Despite the large amount of researches showing that certain beliefs influence and support sexually violent behavior towards women, little is known in terms of cross-cultural differences, especially in developing countries (Fakunmoju et al., 2021). A recent study by Fakunmoju et al. (2021) shows that differences in rape-myths endorsement reflect various patriarchal structures and ideologies, different cultural and religious practices, stereotypes against women, psychological assimilation of values and beliefs as well as victims’ access to protection and police responses to violence.

Honor concerns (Guerra et al., 2015) is also a relevant construct for the explanation of different types of behavior, including violent behavior. According to Gouveia et al. (2013) in honor cultures (such as the Brazilian culture), high levels of honor concern have been shown as an important predictive component for behaviors “that threaten people and their interpersonal relationships when moral standards are not met” (p. 583) —as in the case of sex crimes. Thus, this study contributes not only to the theoretical enrichment of the literature, but also to the advancement of the discussion on sexual aggression against women in Brazil —and on the different ways to prevent and resolve it.

Altogether, our results demonstrate that, for this group of people, the understanding of the phenomenon of sexual violence against women is heavily dominated by the idea that women may overstate the gravity of the violence they have suffered and that men, due to being unable to control their bodily impulses and desires, should not be entirely blamed for this type of violence. It is important to point out that these findings do not refer to a new phenomenon, but rather to one that has already been discussed in the literature (i.e., rape myths; Burt, 1980).

Additionally, our results indicate that although jurisdictional discourse and current practices have gained new contours, they still entail a conservative morality, due to their endorsement of conservative social norms—gender norms among them. Bitton and Jaeger (2019) have shown that police officers tend to accept rape myths more than students independent of the officer gender, and this acceptance is explained by gender role stereotypes. As pointed out by Guerra et al. (2015), stereotypes associated with both women and femininity as well as men and masculinity, still contribute to the maintenance of a traditional view of gender roles, serving to naturalize and justify male dominance over women.

Specifically, about honor concerns, our results showed that family or masculine honor function as predictive factors for two of the four dimensions of rape myths. This sheds light on how the emphasis on gender norms is linked to beliefs underpinning the perpetration of sexually aggressive discourses and practices (such as rape myths). As discussed by Belo (2003), this association serves a social purpose: the defense of family reputation, and often is used as an excuse for the perpetration of violent sexual acts.

In relation to masculine honor, Guerra et al. (2015) and Rodriguez Mosquera et al. (2002) comment that this dimension is linked to an appreciation of the traditional male role, and to a conservative view of social norms. It helps society demarcate social differences between genders, creating unequal power dynamics (Scarpati, 2013). These remarks follow the same general direction of previous theoretical proposals claiming that honor cultures establish normative standards of behavior for all members (Gouveia et al., 2013). Therefore, not only dimensions related to gender (e.g., masculine honor), but also dimensions related to family dynamics, are relevant for the understanding the way people deal with cases of sexual violence against women, and for a better understanding of this phenomenon.

Our results further indicated that those who emphasize materialistic needs of physiological maintenance and body health do not tend to endorse violent representations, whereas individuals who agree with traditional values and norms and obedience to authorities are more likely to directly or indirectly promote sexist speeches and behaviors, blaming women for sexual violence perpetrated by men (Belo et al., 2005). Our findings do indeed show that normative values, characterized by moral conservatism, functioned as predictors for one of the four rape myths dimensions (It is her fault).

Another highlight is the fact that every rape myth dimension was significantly predicted by the participant’s gender; with men being more in agreement with rape myths than women. Respondents’ gender seems to be an important element for the understanding of heterosexual relationships, as it can be a predictor for both the perpetration of violence and the justification of previously perpetrated acts (Bitton & Jaeger, 2019; Gouveia et al., 2013; Rodriguez Mosquera et al., 2002). This shows the importance of considering gender as a relevant analysis variable, reaffirming the need for an educational program specifically targeting this audience (Brown & Testa, 2008).

Collectively, these results also suggest that although progress has been made regarding the discussion of the objective elements of sexual aggression, in order to offer an adequate assistance to victims, the human aspect must also be thoroughly accounted for. As pointed out by Hayes et al. (2013, p. 26), if legal workers, including judges, believe that every human being “gets what they deserve and deserve what they get” and endorses discourses such as “some women ask for it” (Burt, 1980), how can we assure that victims receive a fair and impartial treatment? In other words, what are the effects of personal beliefs on the practice of the law?

According to Marisa Jansen, in an interview about violence against women in Brazil, “the woman victim of sexual violence who seeks the [aid of the] justice system wants the rapist to be blamed, punished. She does not want to be re-victimized, humiliated and ‘judged’” (Brandino, n.d.). However, is it really possible to punish offenders if the responsibility for the perpetrated violence is aprioristically attributed to the victim? Moreover, how can victims be assisted and supported if rape is deemed as “not so serious,” “not as relevant as other crimes,” or not even real? Victim credibility is a vital part of the decision-making process, made by either the family, friends, the society in general and/or the police, lawyers, and judges (Fakunmoju, 2022).

According to Bloom (2009), beliefs, opinions and attitudes about a given social object (e.g., gender norms) can be activated in order to preserve and justify inequalities and, as a last resort, legitimize the perpetration of violence. Thus, discussing this topic not only in the legal system, but also during college years is extremely important not only for Law students, but for all professionals involved in treating and providing care to rape victims.

An adequate level of assistance will only be reached if professionals such as lawyers, police officers, doctors and officials are aware of all variables related to the perpetration of this offence, the consequences for victims’ lives, and of how their decisions and discourse directly affects victims’ lives (Hayes et al., 2013). Precisely, in the sense that by blaming the victim, removing the perpetrator’s responsibility for the act and/or denying the existence of violence, practitioners might simultaneously prevent victims to come forward and report the offence, whilst keep offenders away from suffering the consequences for their acts (Bohner et al., 2010; Smith & Skinner, 2017).

Limitations and future directions

Potential limitations of this research were its convenience sample, formed only by students in their final year of Law school, who mostly belonged to the upper strata of middle class. This may have interfered on our results to a certain extent. We also believe that, despite the relevance of our results, the sample size was rather limited, and thus these results may have a regional coloration. In this sense, the generalization of the data obtained and reported herein require careful consideration.

Another important limitation is related to the internal consistency of the rape myths subscale ‘It is not his fault’, which was below the cutoff point of 0.70 suggested by the literature. Considering that Cronbach's alpha value reflects a low association between the items, and that the four items that make up this factor are related to an idea that men do not have control over themselves regarding sexual behavior, the low consistency may indicate a change in the way society perceives masculinity and what would be considered natural in terms of behavior. Scarpati et al. (2014) suggest the development of new items that might reflect specific culturally-driven content for this factor. However, it is also relevant to point out that this value is still considered within an acceptable level for research purposes (Hair et al., 2009) and that Cronbach's alpha values tend to be lower than those obtained by other reliability assessment techniques (Sijtsma, 2009).

As a future research suggestion, we recommend investigations on whether the aforementioned rape myths can also be found among professionals from various fields who either directly or indirectly interact with victims and/or sex offenders, as well as established professionals of the legal system. We also suggest studies including students in other semesters of the undergraduate Law program; this would allow one to verify, for example, if the educational process itself interferes with students’ acceptance of rape myths.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the CAPES Foundation for their financial support, by means of a Masters’ degree scholarship granted to the first author.

References

Basile, K. C., Smith, S. G., Breiding, M. J., Black, M. C., & Mahendra, R. R. (2014). Sexual Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 2.0. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/sv_surveillance_definitionsl-2009-a.pdf

Belo, R. P. (2003). A base social das relações de gênero: Explicando o ciúme romântico através do sexismo ambivalente e dos valores humanos básicos. [Master thesis]. Universidade Federal da Paraíba.

Belo, R. P., Gouveia, V. V., Raymundo, J. S., & Marques, C. M. C. (2005). Correlatos valorativos do sexismo ambivalente. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 18(1), 7-15. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-79722005000100003

Bitton, M. S., & Jaeger, L. (2019). “It Can’t Be Rape”: Female vs. Male Rape Myths Among Israeli Police Officers. Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology,35, 494-503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-019-09327-4

Bloom, S. L. (2009). Domestic Violence. In O'Brien, J. (Ed) Encyclopedia of Gender and Violence. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications (pp.216-221).

Bohner, G., Pina, A., Viki, G. T., & Siebler, F. (2010). Using social norms to reduce men's proclivity: Perceived rape myth acceptance of acceptance of out-groups may be more influential than that in in-groups. Psychology, Crime and Law, 16(8), 671-693. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2010.492349

Brandino, G. (n.d.). Ministério Público deve zelar pela não revitimização da vítima de estupro, defende promotora do caso New Hit. https://www.compromissoeatitude.org.br/ministerio-publico-deve-zelar-pela-nao-revitimizacao-da-vitima-de-estupro-defende-promotora-do-caso-new-hit/

Brown, A. L., & Testa, M. (2008). Social Influence on Judgments of Rape Victims: The Role of the Negative and Positive Social Reactions of Others. Sex Roles, 58, 490-500. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9353-7

Burt, M. R. (1980). Cultural myths and supports for rape. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 217-230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.38.2.217

Cerqueira, D., & Coelho, D. S. C. (2014). Estupro no Brasil: uma radiografia segundo os dados da Saúde, Nota Técnica 11. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/5780/1/NT_n11_Estupro-Brasil-radiografia_Diest_2014-mar.pdf

Chapleau, K. M., & Oswald, D. L. (2010). Power, Sex, and Rape Myth Acceptance: Testing Two models of Rape Proclivity. Journal of Sex Research, 47(1), 66-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902954323

Cieciuch, J., & Schwartz, S. H. (2017). Values. In V. Zeigler-Hill, & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp.1-5). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28099-8_1509-1

Coulouris, D. G. (2010). The distrust of the victim’s moral and the meaning of punishment in rape judicial lawsuits (in Portuguese) [Doctorate Thesis]. Universidade de São Paulo. https://doi.org/10.11606/T.8.2010.tde-20092010-155706

Eyssel, F., & Bohner, G. (2011). Schema Effects of Rape Myth Acceptance on Judgments of Guilt and Blame in Rape Cases: The Role of Perceived Entitlement to Judge. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(8), 1579-1605. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510370593

Eyssel, F., Bohner, G., & Siebler, F. (2006). Perceived rape myth acceptance of others predicts rape proclivity: social norm or judgmental anchoring? Swiss Journal of Psychology, 65(2), 93-99. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.65.2.93

Fakunmoju, S. B. (2022). “She Lied”: Relationship Between Gender Stereotypes and Beliefs and Perception of Rape Across Four Countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior,51, 833-847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02119-0

Fakunmoju, S. B., Abrefa-Gyan, T., Maphosa, N. & Gutura, P. (2021). Rape myth acceptance: Gender and cross-national comparisons across the United States, South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria. Sexuality & Culture,25(1), 18-38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-020-09755-z

Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública –FBSP–. (2023). Visível e Invisível: A Vitimização de Mulheres no Brasil - 4ª edição. Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, Datafolha Instituto de Pesquisas. https://forumseguranca.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/visiveleinvisivel-2023-relatorio.pdf

Franiuk, R., Seefelt, J. L., Cepress, S. L., & Vandello, J. A. (2008). Prevalence and effects of rape myths in print journalism: The Kobe Bryant case. Violence Against Women, 14(3), 287-309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801207313971

Gouveia, V. V., Guerra, V. M., Araújo, R. C. R., Galvão, L. K. S., & Silva, S. S. (2013). Preocupação com a honra no Nordeste brasileiro: correlatos demográficos. Psicologia & Sociedade, 25(3), 581-591. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0102-71822013000300012

Gouveia, V. V., Milfont, T. L., & Guerra, V. M. (2014). Functional Theory of Human Values: Testing its content and structure hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 60, 41-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.12.012

Government of Newfoundland and Labrador – Canada. (2014). The Violence Prevention Initiative: Defining Violence and Abuse. https://www.gov.nl.ca/vpi/about/defining-violence-and-abuse/

Guerra, V.M., Giner-Sorolla, R., & Vasiljevic, M. (2013). The importance of honor concerns across eight countries. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 16(3) 298-318. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430212463451

Guerra, V. M., Gouveia, V. V., Araújo, R. C. R., Andrade, J. M., & Gaudêncio, C. A. (2013). Honor Scale: Evidence on construct validity. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(6), 1273-1280. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12089

Guerra, V. M., Scarpati, A. S., Brasil, J. A., Livramento, A. M., & Silva, C. V. (2015). Concepções da masculinidade: suas associações com os valores e a honra. Psicologia e Saber Social, 4(1), 72-88, 2015. https://doi.org/10.12957/psi.saber.soc.2015.14840

Hair, J. F., Tatham, R. L., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados. Bookman.

Hayes, R. M., Lorenz, K., & Bell, K. A. (2013). Victim Blaming Others: Rape Myth Acceptance and the Just World Belief. Feminist Criminology,8(3), 202-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085113484788

Koepke, S., Eyssel, F., & Bohner, G. (2014). “She deserved it”: Effects of sexism norms, type of violence, and victim's pre-assault behavior on blame attributions toward female victims and approval of the aggressor's behavior. Violence Against Women, 20(4), 446-464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801214528581

Lee, R., & Jordan, J. (2014). Sexual assault. In L. Jackson-Cherry, & B. Erford (Eds.), Crisis assessment, intervention, and prevention (pp. 193–217). Pearson.

Miller, L. (2014). Rape: Sex crime, act of violence, or naturalistic adaptation? Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 19(1), 67-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.11.004

Oliveira, Y. F. C. (2009). A honra masculina como defesa nos autos de processo de homicídio (década de 1940 e 1950, Itajaí-SC). Revista Ágora,10, 1-13. https://periodicos.ufes.br/agora/article/view/1943

Page, T. E., & Pina, A. (2015). Moral disengagement as a self-regulatory process in sexual harassment perpetration at work: A preliminary conceptualization. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 21, 73-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.004

Page, T. E., Pina, A., & Giner-Sorolla, R. (2016). “It was only harmless banter!” The development and preliminary validation of the moral disengagement in sexual harassment scale. Aggressive Behaviour, 42(3), 254-273. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21621

Pandjiarjian, V. (2006). 25 years balance of violence against women legislation in Brazil [in Portuguese]. In C. S. G. Diniz, L. P. Silveira, & L. A. L. Mirim (Orgs.), Vinte e cinco anos de respostas brasileiras em violência contra a mulher (1980-2005): Alcances e limites (pp. 78-139). Coletivo Feminista Sexualidade e Saúde.

Payne, D., Lonsway, K., & Fitzgerald, L. (1999). Rape myth acceptance: exploration of its structure and its measurement using the Illinois Rape Myth Acceptance Scale. Journal of Research in Personality, 33(1), 27-68. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2238

Pitt-Rivers, J. (1973). Honra e posição social. In J. G. Peristiany (Org.), Honra e vergonha: Valores das sociedades mediterrâneas (pp. 11-60). Fundação Gulbekian.

Planty, M., Langton, L., Krebs, C., Berzofsky, M., & Smiley-McDonald, H. (2013). Female victims of sexual violence, 1994-2010. Bureau of Justice Statistics, Offie of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. https://doi.org/10.1037/e528212013-001

Porto, M., & Costa, F. (2010). Lei Maria da Penha: as representações do judiciário sobre a violência contra as mulheres. Estudos de Psicologia (PUCCAMP), 27(4), 479-489. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2010000400006

Presidência da República. (August 7, 2009). Law Nº 12.015, Change Title VI from the Special Part of Decree nº 2.848, December 7, 1940, Penal Code (in Portuguese). http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2009/lei/l12015.htm

Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network –RAINN– (n.d.a). Statistics. https://rainn.org/statistics

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network –RAINN– (n.d.b). Statistics. Who are the victims?

https://rainn.org/statistics/victims-sexual-violence

Ramos, M. D. (2012). Reflexões sobre o processo histórico-discursivo do uso da legítima defesa da honra no Brasil e a construção das mulheres.Estudos Feministas, 20(1), 53-73. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24328097

Rodriguez Mosquera, P. M., Manstead, A., & Fischer, A. (2002). The role of honour concerns in emotional reactions to offences. Cognition and Emotion, 16(1), 143-163. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930143000167

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press.

Scarpati, A. S. (2013). Rape myths and legal (im)partiality: perception of Law students about women victims of sexual violence (in Portuguese) [Master Thesis]. Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo.

Scarpati, A. S. (2018). The role of culture and morality on men’s acceptance of sexual aggression myths and perpetration of rape in Brazil and the United Kingdom [Doctorate Thesis]. University of Kent.

Scarpati, A. S., Guerra, V. M., & Duarte, C. N. B. (2014). Adaptação da Escala de Aceitação dos Mitos de Estupro: evidências de validade. Avaliação Psicológica, 13(1), 57-65.

Scarpati, A. S., & Pina, A. (2017). On National and Cultural Boundaries: A Cross-cultural Approach to Sexual Violence Perpetration in Brazil and the United Kingdom. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 23(3), 312-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2017.1351265

Sijtsma, K. (2009). On the use, the misuse, and the very limited usefulness of Cronbach’s alpha. Psychometrika, 74(1), 107-120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-008-9101-0

Smith, O., & Skinner, T. (2017). How rape myths are used and challenged in rape and sexual assault trials. Social and Legal Issues, 26(4), 441-466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0964663916680130

Souza, N. A. (2010). A honra dos “homens de bem”. Uma análise da questão da honra masculina em Processos Criminais de Violência Contra Mulheres em Fortaleza (1920-1940). MÉTIS: História & Cultura. 9(18), 155-170.

Süssenbach, P., Eyssel, F., & Bohner, G. (2013) Metacognitive Aspects of Rape Myths: Subjective Strength of Rape Myth Acceptance Moderates Its Effects on Information Processing and Behavioral Intentions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 28(11) 2250-2272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512475317

Temkin, J., Gray, J. M., & Barrett, J. (2018). Different functions of rape myth use in court: findings from a trial observation study. Feminist Criminology, 13(2), 205-226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085116661627

Vandello, J. A., Cohen, D., Grandon, R., & Franiuk, R. (2008). Stand by your man: Indirect prescriptions for honorable violence and feminine loyalty in Canada, Chile, and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,40(1), 81-104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108326194

World Health Organization –WHO– (2010). Changing cultural and social norms that support violence. In World Health Organization (Eds.), Violence Prevention: The Evidence (pp. 95-109). World Health Organization, Liverpool Centre for Public Health. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/violence-prevention-the-evidence

World Health Organization –WHO– (2021). Violence against women prevalence estimates 2018. World Health Organization, United Nations. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341337/9789240022256-eng.pdf

Notes

*

Research article.

Author notes

a Correspondence author. Email: arielle.psicologia@gmail.com

Additional information

How to cite: Scarpati A. S., Guerra, V. M., & Bonfim, C. N. (2023). Rape Myths, Values, and Honor in Brazilian Law Students. Universitas Psychologica, 22, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy22.rmvh