Social media, which has increasingly become a significant part of our lives with the growing young population each year, is frequently used by many people today. In fact, those who do not have a user profile on social media these days are described as "invisible" in the digital age (Staniewski & Awruk, 2022). Individuals who are visible in the digital age display information about themselves through social media and thereby gain a social visibility (Özdemir, 2016). From this perspective, social media has a structure that incorporates life into itself rather than being a part of life, and it is seen as an element that reorganizes our lives (Aslantaş, 2021). As social media has become more accessible and a more prominent platform in many people's daily lives, examining its impact on individuals is also an important aspect (Dion, 2016). The current effort to be visible on social media can lead to some effects on individuals. This self-presentation can enhance one's social visibility but also leads to complex dynamics regarding self-esteem and peer pressure (Neumayer et al., 2021). For example, according to Youn (2019), social media is about showcasing the best aspects of individuals. Unlike invisible individuals, a group of users is transferring their physical lives to the online environment as is (Staniewski & Awruk, 2022). Undoubtedly, one of the social media platforms where this effort to be visible can be exhibited the most is Instagram.

Instagram is one of the first platforms that come to mind when social media is mentioned. In short, Instagram is a visual-based social media tool that allows users to instantly share the photos or videos they take on their own profiles, accompanied by various filters and effects, and a textual caption (Aslan & Ünlü, 2016; Faelens et al., 2022; Öztürk et al., 2016). Although it has been in our lives for approximately 14 years, it has significantly increased its user base since its introduction in 2010 and has demonstrated its popularity in academic research as well. Although Instagram, like every social media platform, has positive features, it can particularly increase women's desire to look beautiful as it encourages the effort to be visible. The phenomenon known as "Instagram vs. reality" exemplifies how curated, edited images create unrealistic beauty standards that can exacerbate feelings of inadequacy and pressure to conform to these ideals (Foster, 2022). This digital transformation of beauty perception can lead women toward cosmetic surgery while negatively affecting their self-esteem. Especially with the recent updates, the increasing use of face-beautifying effects in Instagram stories in every age population is leading women to dislike their unedited appearances and move away from naturalness. Cosmetic surgery, on the other hand, is defined as surgical procedures performed to improve a person's appearance and enhance their self-esteem (Holliday, 2017). Therefore, it is thought that using these effects may lead women to cosmetic surgery. Because these effects directly make the flawed areas on the face flawless, enlarge the lips, shrink the nose, and provide women with most of the services that a cosmetic expert can offer.

Social media platforms, particularly image-focused Instagram, have transformed into arenas where hundreds of thousands of selfies are shared daily and where filters are widely used, fundamentally altering users' beauty perception and body image. Body image, defined as a subjective reflection of a person's thoughts, feelings, and perceptions about their own body (Sinaj & Meca, 2022), becomes particularly vulnerable in these digital environments. Through social networking sites, women can obtain objectified images, compare themselves to these representations, and present themselves for public viewing and evaluation (Goyal & Gautam, 2024; Seekis et al., 2020). This exposure to idealized imagery, combined with the normalization of filtered selfies, creates a psychological environment where unfiltered photos are considered unusual, affecting users' self-perception and creating unrealistic expectations about natural appearance (Karam et al., 2023; Kleemans et al., 2018).

Self-esteem, characterized as a multidimensional structure that includes not only a person's general evaluation of themselves but also self-worth, self-efficacy, and beliefs about their own value (Kille & Wood, 2012; Seki & Dilmaç, 2020; Spector, 2015; Thomaes et al., 2011; Trzesniewski et al., 2013), becomes directly impacted by these digital beauty standards. The constant exposure to idealized, flawless, and unattainable beauty standards on social media platforms leads individuals, especially women, to negatively evaluate their own bodies and experience feelings of inadequacy (Goyal & Gautam, 2024), resulting in outcomes such as low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy, and negative body image. The inclination towards cosmetic surgery emerges not only from low self-esteem or idealized beauty perception but also from various interconnected factors including the desire for social acceptance, perfectionism, lack of self-confidence, and social media pressure (Brasil et al., 2024; Fardouly & Vartanian, 2015; Karam et al., 2023). This complex relationship between digital beauty standards, self-perception, and surgical acceptance is evidenced by the increasing number of individuals who apply to cosmetic surgery experts with their filtered selfies, stating that they want to look like they do in the photos (Sert-Karaaslan, 2021).

Filtered photos serve as a powerful 'preview' of potential cosmetic surgery outcomes, offering users a glimpse of an enhanced self-image that they may aspire to attain in real life (Sun, 2021). This digital-to-physical beauty aspiration is further evidenced by patients presenting filtered selfies during consultations, using these altered images as tangible reference points for desired outcomes and highlighting the growing influence of digital aesthetics on real-world cosmetic decisions (Sert-Karaaslan, 2021). These digital beautification tools actively encourage self-objectification and body dissatisfaction by creating environments where appearance becomes the primary source of self-worth, causing individuals to constantly scrutinize and compare themselves to often unattainable standards (Veldhuis et al., 2020). The resultant dissatisfaction with natural features, coupled with the alluring possibility of digitally enhanced self-representation, contributes to increased interest in aesthetic enhancements and cosmetic procedures (Sarwer, 2019). Social media algorithms and peer pressure continuously reinforce these stringent beauty ideals, creating cycles where individuals feel compelled to chase unrealistic goals, deepening their body dissatisfaction and inclination towards cosmetic intervention (Silva & Steins, 2023). Research consistently demonstrates strong connections between photo-editing applications and individuals' likelihood of pursuing cosmetic surgery, with those actively engaging in digital photo manipulation being more inclined to both consider and seek cosmetic procedures (Chen et al., 2019; Sun, 2021). Several studies highlight the role of beauty filters in increasing acceptance of aesthetic procedures, suggesting that these tools cultivate perceptions of necessity and intense desires for cosmetic modifications (Alkarzae et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021).

Despite their widespread popularity, there is a significant lack of research exploring the specific psychological effects of Instagram story filters, a notable absence considering their extensive usage by young people (Chen et al., 2019). Existing research in the domain predominantly focuses on photo filters, photoshop applications, and Snapchat filters, leaving a clear gap in our understanding of Instagram story filters and their unique impacts on users (Alkarzae et al., 2020). Furthermore, these filters are relatively new and rapidly evolving, necessitating further investigation into their specific psychological impacts (Sert-Karaaslan, 2021). Compounding this issue is the existing limitation in the availability of validated and reliable measurement tools specifically designed to assess Instagram story filter usage, which has hindered in-depth quantitative studies in this area (Tabak & Kahraman, 2024). Consequently, many of the studies have predominantly relied on qualitative research methods, thus limiting the generalizability and statistical power of their findings (Eshiet, 2020). Considering these limitations, a specific research gap arises concerning the understanding of Instagram story filters and their subsequent effects on self-esteem and the acceptance of aesthetic surgery. It is critical that more quantitative research is conducted to fully elucidate these effects and establish generalizable and statistically significant findings.

This study's main hypothesis is that Instagram's facial beautifying story filters negatively impact women's self-esteem while increasing their acceptance of cosmetic surgery. The background of this hypothesis is based on experiencing face-beautifying filters, observing the comments of those who use them, and especially considering the decreasing age of accepting cosmetic surgery. This research not only enhances scientific literature by utilizing a quantitative approach to systematically investigate the psychological impacts of social media filters and related outcomes but also allows for a more comprehensive understanding of the underlying relationships among the investigated variables. The findings of this research have significant potential to guide the development of targeted programs and interventions that aim to mitigate the adverse effects of digital beautification tools on self-esteem and body image, with a particular emphasis on protecting the mental well-being of young women.

Method

Participants

The participants of the study consist of women who use face-beautifying story filters on Instagram. The sample size calculation table developed by Yazıcıoğlu and Erdoğan (2014) was used to determine the sample. Accordingly, with a 0.05 sampling error, a minimum of 357 participants was considered sufficient for the sample. 506 women, who were reached in accordance with the population, participated in the study by sharing the online questionnaire prepared via Google Forms on various social media platforms (Instagram, WhatsApp, Facebook) and e-mail groups. The participants who participated in the study showed participation based entirely on voluntariness. The mean age of the participants is 31.8, and the standard deviation is 10.5. 44.9 % (227) of the participants are single, 32.2 % (163) are single and have no romantic relationship, and 44.6 % (116) are single but have a romantic relationship. 48.8 % (247) of the participants are employed, and 51.2 % (259) are unemployed. 25.9 % (126) of the participants have primary school-high school education level, and 59.2 % (380) have undergraduate-graduate education level. While 42.1 % (213) of the participants use any photoshop application in their selfie photos, 57.9 % (293) do not. 8.9 % (45) of the participants have had a cosmetic procedure on their face before, while 91.1 % (461) have not. 16.8 % (85) of the participants have had a cosmetic procedure on their face before, while 83.2 % (421) have not. 61.3 % (310) of the participants are considering having a cosmetic or cosmetic procedure, while 38.7 % (196) are not.

Measures

Socio-demographic Form: The form prepared by the researcher includes questions about the participants' age, marital status, employment status, education level, whether they use any photoshop application for their selfie photos, whether they have had aesthetic or cosmetic surgery before, and whether they are considering having an aesthetic or cosmetic procedure.

The Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale (ISFUS): To measure the frequency of participants' use of Instagram story filters and the effect of these filters on beauty perception, the Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale developed by researchers Tabak and Kahraman (2024) was used. The ISFUS is a 5-point Likert-type scale consisting of 2 sub-dimensions and 8 items. The possible responses to the scale items are ordered as (1 = Never, 5 = Always). The minimum score that can be obtained from the scale is 8, and the maximum score is 40. A high score obtained from the scale indicates that the person's use of story filters on Instagram is high and that this situation negatively affects their beauty perception. In addition, high scores obtained from the scale indicate that individuals' levels of compulsive online buying increase. There are no reverse-scored items in the scale. In this study the Cronbach's alpha value is 0.858.

The Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale: This scale was developed by Henderson-King and Henderson-King in 2005, is a 15-item scale created to determine individuals' attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. The ACS Scale is a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 7 = Strongly Agree) and can be evaluated based on both three sub-dimensions and the total score of the scale. The score range of the ACS Scale is 15-105. A high score obtained from the scale indicates that attitudes towards cosmetic surgery are positive. The 10th item on the scale is a reverse-scored item. The Cronbach's alpha value of the scale ranges from 0.91 to 0.93. The Turkish validity and reliability study of the scale was conducted by Karaca et al. in 2017.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: This scale was developed by Rosenberg in 1965. The validity and reliability analysis in our country was conducted by Çuhadaroğlu in 1986. The self-esteem scale consists of 10 items. The questions are scored through the Guttman scaling method. The scoring method of the scale is as follows: questions 1, 2, and 3; questions 4 and 5; and questions 9 and 10 are evaluated together. If any two of the first three questions score, the participant receives 1 point from this set. If one of the scoring options in any of the 4th and 5th questions is marked, 1 point is again received from this set. Questions 9 and 10 are evaluated like questions 4 and 5. Questions 6, 7, and 8 each score on their own. Thus, when the participant scores all questions, the maximum score is 6 points. A score of 0-1 corresponds to a high level of self-esteem, 2-4 corresponds to a moderate level, and 5-6 corresponds to a low level of self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965; Çuhadaroğlu, 1986).

Procedure

The data were obtained through an online questionnaire form prepared using the Google Forms program. Approval was obtained from the Istanbul Beykent University Social Sciences Ethics Committee for the implementation of the research (Date: 20.12.2021, Decision number: 137).

After obtaining informed consent online from the women participating in the study, the data were collected. The prepared questionnaire consists of 4 sections. The first section includes questions aimed at determining sociodemographic information, the second section uses the Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale, the third section uses the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale, and the fourth section uses the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. It was made compulsory to fill out each question, thus ensuring that no answer was left blank. Participants have the right to go back and change the answers while filling out the questionnaire. Since all questions except the age question are multiple choice, participants were able to select only one option. After 506 women completed the questionnaires, online response acceptance was terminated. No time limit was set for completing the questionnaire. Completing the questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes. Participant responses were limited to 1 response from the Google Forms settings section.

Data Analysis

The data were analyzed using the SPSS program (IBM Corporation, 2017). To determine whether the data conformed to a normal distribution, skewness, kurtosis values, and histogram graphs were examined. Since all the data followed a normal distribution, parametric tests were applied in the analysis. In all analyses, p < 0.05 values were accepted as statistically significant. Effect sizes were calculated and interpreted according to Cohen's conventions for practical significance assessment (Cohen, 1988). For correlations, confidence intervals were computed using Fisher's z-transformation to enhance statistical precision and transparency. The data obtained in the study were evaluated with frequency distributions, correlations, simple linear regression, and mean analyses. The variables of having had a cosmetic procedure on the face before, having had a cosmetic procedure on the face before, and considering having a cosmetic or cosmetic procedure were measured with an independent samples t-test.

Findings

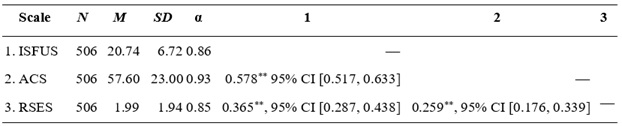

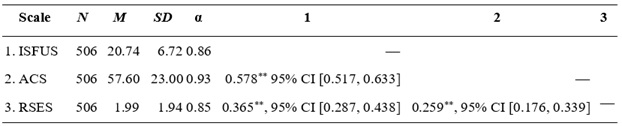

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics,

Reliability Coefficients, and Intercorrelations for Instagram Story Filter Use,

Self-Esteem, and Cosmetic Surgery Acceptance Scales

Note.

**p < .01. ISFUS:

Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale, ACS: Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale,

RSES: Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Higher scores indicate lower levels of

self-esteem and body image satisfaction.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and correlation values for the scales used in the study. The Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale (ISFUS) had a mean of 20.74 (SD = 6.72) and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.86. The Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACS) had a mean of 57.60 (SD = 23.00) and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) had a mean of 1.99 (SD = 1.94) and a Cronbach's alpha of 0.85. A moderate, positive, and significant correlation was found between ISFUS and ACS scores (r = 0.578, 95% CI [0.517, 0.633], p < 0.001). A moderate, positive, and significant correlation was found between ISFUS and RSES scores (r = 0.365, 95% CI [0.287, 0.438], p < 0.001), indicating that higher filter use was associated with lower self-esteem levels. A weak, positive, and significant correlation was found between ACS and RSES scores (r = 0.259, 95% CI [0.176, 0.339], p < 0.001), indicating that higher cosmetic surgery acceptance was associated with lower self-esteem levels.

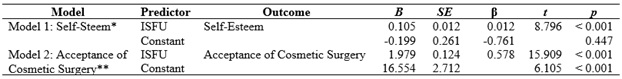

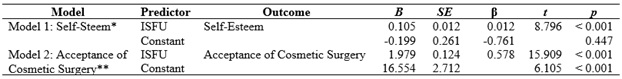

Table 2

Simple Linear Regression Analysis Predicting Self-Esteem

and Cosmetic Surgery Acceptance from Instagram Story Filter Use

Table 2 presents the simple linear regression results for

predicting scores on the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES) and the Acceptance

of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACS) from scores on the Instagram Story Filters

Usage Scale (ISFUS). The results indicated that ISFUS scores significantly

predicted RSES scores, F (1, 505) = 77.37, p < 0.001, with a

standardized coefficient of β = 0.365. ISFUS scores accounted for 13.3 % of the

variance in RSES scores (R² =0 .133, η² = 0.133), representing a large

effect size. Furthermore, ISFUS scores significantly predicted ACS scores, F (1,

505) = 253.09, p < 0.001, with a standardized coefficient of β = 0.578.

ISFUS scores accounted for 33.4 % of the variance in ACS scores (R² = 0.334,

η² = 0.334), also representing a large effect size. These findings indicate

that Instagram story filter use is a strong predictor of both lower self-esteem

and higher cosmetic surgery acceptance among participants.

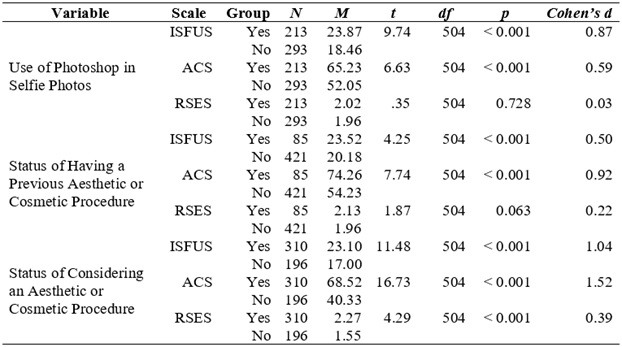

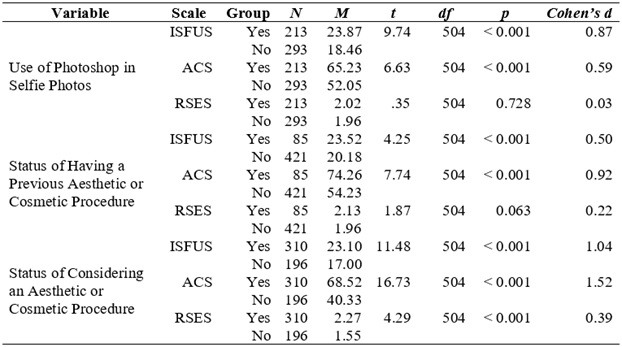

Table 3

Comparison of Instagram Story Filter Use, Cosmetic Surgery Acceptance,

and Self-Esteem Scores by Demographic Characteristics and Cosmetic Procedure

History

Note.

ISFUS: Instagram Story

Filters Usage Scale, ACS: Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale, RSES: Rosenberg

Self-Esteem Scale

Table 3 presents the results of independent samples .-tests comparing scale scores based on the variables of having had a previous aesthetic procedure, having had a previous cosmetic procedure, and considering having an aesthetic or cosmetic procedure. The results of the independent samples .-test for the use of photoshop application in selfie photos revealed no significant difference in Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale scores (p > 0.05, d = 0.03, negligible effect). However, a significant difference was found in favor of women who use photoshop in selfie photos on the Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale (t = 9.74, p < 0.001, d = 0.87, large effect) and the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (t = 6.63, p < 0.001, d = 0.59, medium effect) scores. This indicates that women who use photoshop application in selfie photos have significantly higher levels of Instagram story filter use and acceptance of cosmetic surgery than those who do not.

Similarly, the independent samples .-test for the variable of having had a previous aesthetic or cosmetic procedure on the face revealed no significant difference in Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale scores (p > 0.05, d = 0.22, small effect). However, there was a significant difference in favor of women who had previously had an aesthetic/cosmetic procedure on the face in the scores of the Instagram story filters usage scale (t= 4.25, p< 0.001, d= 0.50, medium effect) and the acceptance of cosmetic surgery scale (t = 7.74, p < 0.001, d = 0.92, large effect). This indicates that women who had previously had aesthetic/cosmetic procedures on their face had significantly higher levels of Instagram story filter use and acceptance of cosmetic surgery than those who had not.

Finally, the analysis of the variable of considering having an aesthetic or cosmetic procedure on the face revealed significant differences on the Instagram story filters usage scale (t = 11.48, p < 0.001, d = 1.04, large effect), the acceptance of cosmetic surgery scale (t = 16.73, p < 0.001, d = 1.52, large effect), and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale (t = 4.29, p < 0.001, d = 0.39, small-to-medium effect) scores. Specifically, women considering having an aesthetic or cosmetic procedure had significantly higher levels of Instagram story filter use and acceptance of cosmetic surgery and lower levels of self-esteem than those not considering such procedures, with particularly large effects observed for filter use and cosmetic surgery acceptance.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the effect of using face-beautifying story filters on the social media platform Instagram on women's attitudes towards cosmetic surgery and their self-esteem. Digital appearance-altering research has predominantly examined photo filters, Snapchat applications, and Photoshop effects, with Instagram story filters representing a relatively understudied area due to limited measurement tools until recently. Existing studies have been largely qualitative (Eshiet, 2020) or focused on other platforms (Burnell et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2019). Our quantitative findings with 506 participants provide significant contributions to understanding these emerging digital beautification technologies and their psychological impacts.

Major findings of this study emerge from regression analyses demonstrating that Instagram story filter use significantly predicts both decreased self-esteem and increased cosmetic surgery acceptance. Particularly noteworthy is that filter use explains 33.4 % of the variance in cosmetic surgery acceptance and 13.3 % of the variance in self-esteem scores. These predictive relationships suggest that Instagram story filters represent significant factors in shaping appearance-related attitudes and self-perception. Higher scores on the self-esteem scale reflected lower self-esteem levels, thus the positive correlation indicates that increased filter use is associated with decreased self-esteem. These regression findings indicate that the use of face-beautifying filters on Instagram significantly affects both women's perceptions of their real appearance and their attitudes towards aesthetic procedures, clearly demonstrating the role of digital beauty filters in shaping individuals' beauty perceptions and their relationship with aesthetic intervention tendencies.

Supporting these primary regression findings, t-test analyses reveal a concerning cyclical phenomenon that further illuminates the psychological mechanisms at work. Women who have undergone previous aesthetic or cosmetic facial procedures demonstrate significantly higher levels of Instagram story filter use, more negative beauty perceptions resulting from filter use, and greater acceptance of additional cosmetic surgery compared to women without surgical history. This pattern indicates that aesthetic interventions, rather than resolving appearance dissatisfaction, perpetuate and intensify the cycle of appearance modification behaviors, with filter use serving as both a precursor to and consequence of cosmetic surgery.

This cyclical process represents a fundamental departure from conventional beauty enhancement paradigms. Traditional cosmetic surgery literature consistently demonstrates that successful procedures typically result in high patient satisfaction rates, with studies showing satisfaction rates of 86-98 % and improvements in psychological well-being within the first years following surgery (Castle et al., 2002; Sarwer et al., 2005; Sarwer et al., 2008). Contemporary evidence continues to support these traditional satisfaction patterns, with recent data showing that up to 95% of breast augmentation patients and 91% of rhinoplasty patients report they would undergo the procedure again (American Society of Plastic Surgeons, 2024). Cross-cultural studies further confirm that cosmetic surgery generally results in high satisfaction rates, with 87% of patients reporting satisfaction along with positive impacts on emotional well-being and confidence (Al-Jumah et al., 2021; Handini & Antonio, 2023).

The underlying assumption in cosmetic surgery practice has been that successful aesthetic interventions should increase satisfaction and reduce further intervention desires, leading to improved self-esteem and body image (Honigman et al., 2004). Research has shown that most patients report sustained improvements in body image and overall appearance satisfaction through two years post-surgery, with these positive outcomes remaining stable over time (Sarwer et al., 2008). However, our findings demonstrate that Instagram filters create digitally perfected standards that remain unattainable even post-surgery, leading to continued dissatisfaction and ongoing pursuit of both digital and surgical enhancement. This contradicts the traditional model where cosmetic surgery was expected to provide definitive satisfaction and psychological improvement. The phenomenon suggests that women initially pursue cosmetic procedures to achieve their filtered appearance in reality, but subsequently continue using filters post-surgery while simultaneously seeking additional surgical interventions to match their ever-evolving digital self-image.

Understanding this cyclical phenomenon requires examining how traditional social comparison processes have evolved in digital environments. While Festinger's (1954) social comparison theory originally explained how individuals evaluate themselves relative to others, Instagram filters introduce a novel dynamic: users now compare themselves to enhanced versions of their own appearance rather than solely to external idealized images. This 'digital self-comparison' perpetuates the cycle we observed because filtered self-images create personalized, internalized beauty standards that remain unattainable, driving continued filter use and surgical interventions.

Traditional social comparison theory has been extensively applied to understand how media exposure affects body image and self-perception (Myers & Crowther, 2009). Recent meta-analytic evidence demonstrates that online social comparison is significantly associated with greater body image concerns and eating disorder symptoms, with these effects being particularly pronounced in digital environments. Contemporary research reveals that nearly 85 % of emerging adults use social media platforms, with increased body dissatisfaction and appearance comparisons being documented in recent years (Brasil et al., 2024). This digital self-comparison to one's enhanced avatar creates an internalized and personalized beauty standard that may be more psychologically compelling than external comparisons to others.

Research in objectification theory provides additional theoretical support, demonstrating that when individuals adopt an observer's perspective on their own bodies, it leads to increased self-surveillance and body monitoring, consuming significant cognitive resources while perpetuating dissatisfaction with natural appearance (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Meta-analytic evidence confirms that appearance-focused social comparisons are strongly associated with body dissatisfaction and reduced psychological well-being, with effect sizes indicating clinically meaningful impacts (Myers & Crowther, 2009). The post-surgical continuation of filter use observed in our study suggests that digital beautification tools may contribute to altered perception patterns, creating a state of chronic appearance dissatisfaction regardless of objective physical improvements achieved through cosmetic procedures.

The relationship between Photoshop application use and other variables further supports these patterns. Women using Photoshop in selfie photos demonstrated significantly higher Instagram story filter use, more negative beauty perceptions, and greater cosmetic surgery acceptance, indicating a general tendency toward cross-platform visual manipulation. This aligns with Sun's (2021) findings that selfie editing provides previews of potential post-surgical appearances, thereby increasing procedure acceptance. Clinical evidence supports this relationship, with cosmetic surgeons reporting that patients increasingly reference their own filtered images when describing desired surgical outcomes (Sert-Karaaslan, 2021; American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 2019).

Regarding self-esteem relationships, our findings present a nuanced picture that partially diverges from some previous research. While we found no significant self-esteem differences between women who had undergone cosmetic procedures and those who had not, women currently considering such procedures showed significantly lower self-esteem levels. This contrasts with some studies (Chen et al., 2019; Rajanala et al., 2018) that found direct relationships between digital manipulation and reduced self-esteem. The moderate self-esteem levels observed across our predominantly young adult sample may reflect the more established self-structure in this demographic compared to adolescent populations, potentially limiting the detection of subtle digital beautification effects on self-concept.

Implications

Based on the results of this research, various recommendations can be developed for both clinical practitioners and future research. First, it is important for cosmetic surgery experts to inform their patients who apply with filtered selfie photos about unrealistic expectations and to emphasize the artificial beauty perception created by social media filters in these consultations. It is recommended that clinicians, especially when working with young women, evaluate the effects of social media use on body image and self-esteem and develop interventions that raise awareness on this issue.

Experts working in the field of mental health should consider the relationship between the intensive use of Instagram story filters and psychological problems such as eating disorders, depression, and dysmorphic disorders, especially in individuals in adolescence and young adulthood. In this context, early identification of risk groups and the development of preventive intervention programs are of great importance. In addition, it will be beneficial to implement programs in schools and youth centers that will increase social media literacy, support realistic body image, and promote self-confidence.

For future research, it is recommended to examine the relationship between the Instagram Story Filters Usage Scale and different psychological variables. In particular, the long-term psychological effects of filter use can be investigated with longitudinal studies. In addition, conducting comparative studies between different age groups and socioeconomic levels will contribute to a better understanding of risk factors. Furthermore, it is important to regularly evaluate the psychological effects of newly emerging digital beauty trends, taking into account the constantly evolving and changing structure of social media platforms. Finally, at the social level, it is recommended to raise awareness about the role of media organizations and social media platforms in spreading unrealistic beauty standards and to work to ensure that these platforms develop more responsible policies. In this context, it will be beneficial to organize awareness campaigns targeting young users and to provide warning information about the use of filters/effects. The implementation of all these recommendations will contribute to reducing the negative effects of social media on body image and self-esteem and creating a healthier digital media usage culture.

References

Al-Jumah, M. M., Al-Wailiy, S. K., & Al-Badr, A. (2021). Satisfaction survey of women after cosmetic genital procedures: A cross-sectional study from Saudi Arabia. Aesthetic Surgery Journal Open Forum, 3(1), ojaa048. https://doi.org/10.1093/asjof/ojaa048

Alkarzae, M., Aldosari, B., Alalula, L., Almuhaya, R., & Alawadh, I. (2020). The effect of selfies on cosmetic surgery. ENT Updates, 10(1), 251-260. https://doi.org/10.32448/entupdates.664150

American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. (2018, January). AAFPRS 2018 annual survey reveals key trends in facial plastic surgery [Press release]. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/aafprs-2018-annual-survey-reveals-key-trends-in-facial-plastic-surgery-300782534.html

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. (2024). 2024 plastic surgery statistics report. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics

Aslan, A., & Ünlü, D. G. (2016). Instagram fenomenleri ve reklam ilişkisi: Instagram fenomenlerinin gözünden bir değerlendirme [A research on the relationship between Instagram phenomenons and advertisers]. Maltepe Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Dergisi, 3(2), 41-65.

Aslantaş, M. (2021). Sosyal medya kullanımının düğün fotoğrafçılığına etkisi [Social media usage to wedding photography effect]. Erzurum Teknik Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi, (13), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.29157/etusbed.895652

Brasil, K. M., Mims, C. E., Pritchard, M. E., & McDermott, R. C. (2024). Social media and body image: Relationships between social media appearance preoccupation, self-objectification, and body image. Body Image, 51, 101767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2024.101767

Burnell, K., Kurup, A. R., & Underwood, M. K. (2021). Snapchat lenses and body image concerns. New Media & Society, 24(9), 2088-2106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444821993038

Castle, D. J., Honigman, R. J., & Phillips, K. A. (2002). Does cosmetic surgery improve psychosocial wellbeing? Medical Journal of Australia, 176(12), 601-604. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04593.x

Chen, J., Ishii, M., Bater, K. L., Darrach, H., Liao, D., Huynh, P. P., Reh, I. P., Nellis, J. C., Kumar, A. R., & Ishii, L. E. (2019). Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 21(5), 361-367. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Çuhadaroğlu, F. (1986). Adolesanlarda benlik saygısı [Self-esteem in adolescents] [Unpublished master's thesis, Hacettepe Üniversitesi].

Dion, N. (2016). The effect of Instagram on self-esteem and life satisfaction [Bachelor’s thesis, Salem State University]. Digital Repository Salem State University. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.13013/892

Eshiet, J. (2020). Real me versus social media me: Filters, Snapchat dysmorphia and beauty perceptions among young women [Master's thesis; California State University San Bernardino]. Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/1101/

Faelens, L., Hoorelbeke, K., Cambier, R., van Put, J., Van de Putte, E., De Raedt, R., & Koster, E. H. W. (2021). The relationship between Instagram use and indicators of mental health: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100121

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one's appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Foster, J. (2022). "It's all about the look": Making sense of appearance, attractiveness, and authenticity online. Social Media + Society, 8(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221138762

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. -A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Goyal, D., & Gautam, S. K. (2024). Impact of social media on body image perception and self esteem among young women. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 6(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.36948/ijfmr.2024.v06i02.17285

Handini, N. S., & Antonio, F. (2023). Patients' tendency to recommend plastic surgery clinic shaped by appearance consciousness. Health SA Gesondheid, 28, a2320. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v28i0.2320

Henderson-King, D., & Henderson-King, E. (2005). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Scale development and validation. Body Image, 2(2), 137-149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.003

Holliday, R. (2017). Ego is the enemy. Editorial Planeta.

Honigman, R. J., Phillips, K. A., & Castle, D. J. (2004). A review of psychosocial outcomes for patients seeking cosmetic surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 113(4), 1229-1237. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000110214.88868.ca

IBM Corporation. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 25.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corporation. https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics

Karaca, S., Karakç, A., Onan, N., & Kadıoğlu, H. (2017). Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Acceptance of Cosmetic Surgery Scale (ACSS). Journal of Psychiatric Nursing, 8(1), 17-22. https://doi.org/10.14744/phd.2017.72692

Karam, J. M., Bouteen, C., Mahmoud, Y., Tur, J. A., & Bouzas, C. (2023). The relationship between social media use and body image in Lebanese university students. Nutrients, 15(18), 3961. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15183961

Kille, D. R., & Wood, J. V. (2012). Self-esteem. In V. S. Ramachandran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (2nd ed., pp. 321-327). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-375000-6.00313-X

Kleemans, M., Daalmans, S., Carbaat, I., & Anschütz, D. (2018). Picture perfect: The direct effect of manipulated Instagram photos on body image in adolescent girls. Media Psychology, 21(1), 93-110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2016.1257392

Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H. (2009). Social comparison as a predictor of body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(4), 683-698. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016763

Neumayer, C., Rossi, L., & Struthers, D. M. (2021). Invisible data: A framework for understanding visibility processes in social media data. Social Media + Society, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120984472

Özdemir, Z. (2016). Sosyal medyada kimlik inşasında yeni akım: Özçekim kullanımı [New trend in identity achievement in social media: Using selfies]. Maltepe Üniversitesi İletişim Fakültesi Dergisi, 2(1), 112-131.

Öztürk, E., Şener, G., & Süher, H. K. (2016). Sosyal medya çağında ürün yerleştirme: Instagram ve Instabloggerlar üzerine bir içerik analizi [Product placement in the social media era: A content analysis on Instagram and Instabloggers]. Global Media Journal TR Edition, 6(12), 355-386.

Rajanala, S., Maymone, M. B. C., & Vashi, N. A. (2018). Selfies—Living in the era of filtered photographs. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 20(6), 443-444. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2018.0486

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

Sarwer, D. B. (2019). Body image, cosmetic surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. Body Image, 31, 302-308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.009

Sarwer, D. B., Gibbons, L. M., Magee, L., Baker, J. L., Casas, L. A., Glat, P. M., Gold, A. H., Jewell, M. L., LaRossa, D., Nahai, F., & Young, V. L. (2005). A prospective, multi-site investigation of patient satisfaction and psychosocial status following cosmetic surgery. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 25(3), 263-269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2005.03.009

Sarwer, D. B., Infield, A. L., Baker, J. L., Casas, L. A., Glat, P. M., Gold, A. H., Jewell, M. L., LaRossa, D., Nahai, F., & Young, V. L. (2008). Two-year results of a prospective, multi-site investigation of patient satisfaction and psychosocial status following cosmetic surgery. Aesthetic Surgery Journal, 28(3), 245-250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2008.02.003

Seekis, V., Bradley, G. L., & Duffy, A. L. (2020). Appearance related social networking sites and body image in young women: Testing an objectification-social comparison model. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(3), 377-392. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684320920826

Seki, T., & Dilmaç, B. (2020). Benlik saygısı ve ilişkisel faktörler: Bir meta-analiz çalışması [Self-esteem and relational factors: A meta-analysis study]. Türk Eğitim Bilimleri Dergisi, 18(2), 853-873. https://doi.org/10.37217/tebd.735112

Silva, R. C., & Steins, G. (2023). Social media and body dissatisfaction in young adults: An experimental investigation of the effects of different image content and influencing constructs. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1037932. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1037932

Sinaj, E., & Meca, X. (2022). Body image and self-esteem in teenagers. Polis, 21(2), 34-46. https://doi.org/10.58944/uucf5880

Spector, P. E. (2015). Self-esteem. In C. L. Cooper, P. C. Flood, & Y. Freeney (Eds.), Wiley encyclopedia of management. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118785317.weom110252

Staniewski, M., & Awruk, K. (2022). The influence of Instagram on mental well-being and purchasing decisions in a pandemic. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 174, 121287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121287

Sun, Q. (2021). Selfie editing and consideration of cosmetic surgery among young Chinese women: The role of self-objectification and facial dissatisfaction. Sex Roles, 84, 670-679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01191-5

Tabak, M. Y., & Kahraman, S. (2024). Instagram Story Effects Usage Scale (ISEUS): A scale for user tendencies in social media. Turkish Psychological Counseling and Guidance Journal, 14(74), 388-400. https://doi.org/10.17066/tpdrd.1387769_7

Thomaes, S., Poorthuis, A., & Nelemans, S. (2011). Self-esteem. In B. Brown & M. J. Prinstein (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 316-324). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-373951-3.00037-5

Trzesniewski, K. H., Donnellan, M. B., & Robins, R. W. (2013). Development of self-esteem. In V. Zeigler-Hill (Ed.), Self-esteem (pp. 60-79). Psychology Press.

Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Bij de Vaate, A. J. D. (N.), Keijer, M., & Konijn, E. A. (2020). Me, my selfie, and I: The relations between selfie behaviors, body image, self-objectification, and self-esteem in young women. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 9(1), 3-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000206

Wang, Y., Fardouly, J., Vartanian, L. R., Wang, X., & Lei, L. (2021). Body talk on social networking sites and cosmetic surgery consideration among Chinese young adults: A serial mediation model based on objectification theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 46(1), 99-110. https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843211026273

Yazıcıoğlu, Y., & Erdoğan, S. (2014). SPSS uygulamalı bilimsel araştırma yöntemleri [SPSS applied scientific research methods]. Detay Yayıncılık.

Youn, S. -Y. (2019). Connecting through technology: Smartphone users' social cognitive and emotional motivations. Social Sciences, 8(12), 326. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8120326

Sert-Karaaslan, Y. (2021, April 11). Sosyal medya kullanımı ve özçekim gençlerde estetik kaygıyı artırıyor [Social media use and selfies increase aesthetic anxiety in young people]. Anadolu Ajansı. https://www.aa.com.tr/tr/saglik/sosyal-medya-kullanimi-ve-ozcekim-genclerde-estetik-kaygiyi-artiriyor/2205094

Notes

*

Research article.

Author notes

a Correspondence author. Email: suleymankahraman@beykent.edu.tr

Additional information

How to cite: Tabak, M. Y., & Kahraman, S. (2025). Social

Media-Induced Body Image Manipulations: The Psychological Effects of Instagram

Story Filters on Cosmetic Surgery and Self-Esteem. Universitas Psychologica, 24, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy24.smib