In recent decades, digital social networks have become an inherent part of daily life, particularly among younger generations, whose social interaction, access to information, and decision-making processes are markedly shaped by these platforms (Shanmugasundaram & Tamilarasu, 2023). This change has fundamentally altered the way people think and share information, producing profound shifts in contemporary cognitive and cultural dynamics (Purnama & Asdlori, 2023). According to Torous et al. (2021), this evolution has generated a model of social coexistence increasingly mediated by digital interactions, where immediacy and global connectivity prevail over traditional modes of socialisation. Far from being static, this dynamic has been intensified by successive technological advances (Knell, 2021), most notably the exponential development of artificial intelligence (AI), now inseparable from the creation, curation, and dissemination of content in the digital ecosystem (Theodorakopoulos et al., 2025).

The enormous development of AI has contributed to the generation of incredibly realistic simulations that blur lines between reality and fiction (Duan et al., 2022). Powered by algorithms to continually personalize content, AI optimises information exposure whilst also moulding users’ interpretive systems (Erafy, 2023). According to Ienca (2023), this algorithmic and media manipulation can produce perceptual distortions and can change the overall understanding of reality. Indeed, Prasad and Bainbridge (2022) describe how these processes result in the emergence of shared false memories, which would eventually lead to what is now known as the Mandela Effect.

First described as the collective generation of inaccurate memories, the Mandela Effect is now unfolding in an unprecedented context: the emergence of AI systems that amplify and refashion narratives through content created artificially and through modified content (MacLin, 2023). This presents a unique threat to younger generations (who are heavy social media users) who are more susceptible to AI-induced cognitive distortions (Sireli et al., 2023). Despite having much to say on the relevance of studying the Mandela Effect in AI-mediated environments, the current literature remains largely lacking validated instruments for empirical evaluation (Prasad & Bainbridge, 2022; Rüther, 2024).

Therefore, an urgent effort is required for the development and validation of instruments that are multimodal in integrating the cognitive, technological, and social dimensions of this concept. Though some initial studies have explored scales involving memory distortion and misinformation exposure (Gerlich, 2023), none have comprehensively addressed the Mandela Effect specifically induced by AI in digital social networks (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025). This study fills this gap by developing and testing an effective psychometric instrument, the “Mandel-AI Effect,” using exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses. The aim is to present a reliable, multidimensional instrument for assessing this phenomenon, contributing theoretical and methodological foundations for understanding the cognitive and social implications of AI in shaping collective memory and perceptions of reality, with potential applications in media literacy, digital communication, and mental health.

Theoretical framework

Thus, the theoretical approach to the Mandel-AI Effect should incorporate concepts from cognitive psychology, digital communication, and artificial intelligence studies to understand the complex interaction between collective memory, algorithmic manipulation, and digital social networks. The extant literature has, however, described this phenomenon in a fragmented way, in terms of how AI-mediated digital spaces (e.g., social media and other virtual ecosystems) may lead to differences in perception and the construction of joint narratives, and the heightening impact of false memory phenomena (Rüther, 2024). Given that no unified conceptual framework for the convergence of these processes exists, a robust mechanism to measure their impact empirically remains to be developed (Prasad & Bainbridge, 2022). Thus, the existing theoretical paradigm is organized around variables that permit the important aspects of the phenomenon to be decomposed and establish the foundations for the methodological proposal that follows.

Presence of Artificial Intelligence in Social networks

In the contemporary digital ecosystem, AI has become an essential part of the functional dynamics of social networks, acting as a driving force in the generation, curation, and distribution of content (Hussain et al., 2023). Its integration goes beyond technical tasks invisible to users and directly permeates the browsing experience, determining which posts are prioritised, which topics go viral, and which interactions are encouraged (Anantrasirichai & Bull, 2021). This role is supported by algorithmic systems capable of processing large volumes of data in real time to predict, model, and shape users’ interests and behaviours (Allal-Chérif et al., 2021). Consequently, exposure to digital content ceases to be a random or purely social process, becoming an experience mediated by computational decisions that, while optimising apparent relevance, also condition access to diverse perspectives and narratives (Essien, 2025).

In practice, such as managing viral trends and picking content that has high interaction potential (Swart, 2021), AI assumes a predominant role in shaping the digital agenda as evidenced by the empirical evidence. Such filtering and amplification operations depend on algorithmic systems which leverage machine learning, data mining, and semantic analysis for observing consumption data and predicting virality (Agha, 2025). Thus, the visibility of information is no longer determined solely by organic user interaction but also by systems that are built to maximise metrics like dwell time, clicks, or conversion (Muralidhar & Lakkanna, 2024). Through this logic, an environment arises wherein AI is both responsive to and actively shapes information demand (Spring et al., 2022).

Furthermore, users’ recognition of AI’s presence is key to understanding its psychological and social influence (Wu et al., 2024). According to Rodilosso (2024), an increasing number of users identify AI intervention in the content they consume, associating it with changes in how they access information and form opinions. This recognition extends to perceptions that AI shapes virality and personal feeds, affecting perceived autonomy in information selection and trust in platforms. Similarly, Theodorakopoulos et al. (2025) argue that the interaction between automated recommendation systems and social networks forms an ecosystem of persistent influence, where algorithms act as invisible mediators of perceived reality.

Research thus suggests that algorithmic mediation not only enhances user experience but also redefines information hierarchies, shaping the collective imagination through opaque automated decisions (Chan et al., 2023). Therefore, “Presence of AI in Social Networks” must be viewed as a variable involving acknowledgement of AI's role in content generation, its impact on virality, and its intervention in post prioritisation. This variable is evaluated via four individual items representing explicit perceptions of algorithmic presence, influence, and control. This approach provides an empirical framework by which it is possible to investigate how AI itself intervenes in reality construction processes, and, by extension, in phenomena like distortion and the Mandel-AI Effect.

Distortion of reality in social networks

In digital social platforms, reality distortion arises from interaction with AI-generated or AI-manipulated content who’s visual and narrative realism challenges perceptual limits (Sun et al., 2024). This distortion is experienced subjectively, blurring the boundaries between reality and fiction and impairing the assessment of information truthfulness (Williamson & Prybutok, 2024). As Ghiurău and Popescu (2025) note, the integration of synthetic content into massive information flows increases exposure to falsified stimuli while weakening cognitive mechanisms for detecting inconsistencies. AI’s ability to create realistic images, videos, and texts eliminates traditional signs of manipulation, making them difficult to identify (Cooke et al., 2024).

Trigka and Dritsas (2025) note the confusion between real and fake content is not limited to the technical domain but is also a cognitive and emotional process where credibility is increased through repetition and virality. Algorithms of personalisation further amplify interpretative mechanisms that underwrite false narratives (Lu, 2024) and continuous exposure to AI-generated imagery progressively undermines the capacity to separate fact from simulation, promoting confusion that has implications for memory and decision-making (Jang et al., 2025). The visual element is particularly influential, as AI-generated images are both convincing and difficult to contradict (Momeni, 2024), thereby resulting in implications for both personal comprehension and collective memory (Matei, 2024). Over exposure to manipulated visuals distorts interpretations of past and present events and reshapes constructs of reality to disrupt epistemic trust in sources (Makhortykh et al., 2023).

Thus, “Distortion of Reality in Social Networks” integrates these cognitive and perceptual processes within a latent variable that captures AI’s role in generating confusion and uncertainty about what is real. In this study, it is operationalised through items assessing recognition of AI’s capacity to alter perception, the difficulty of distinguishing between true and false, and confusion induced by AI-generated imagery.

Mandel-AI effect

The Mandela Effect refers to a collective memory phenomenon in which groups consistently recall events or narratives that never occurred or differ from reality (Prasad & Bainbridge, 2022). Traditionally explained through mnemonic reconstruction, cognitive biases, misinformation exposure, and social validation of false memories (Hussein, 2025), this effect has been magnified by AI’s capacity to generate and manipulate digital content disseminated through social networks (Hu, 2024). Using deepfakes and generative models, AI produces highly convincing visual and textual materials that challenge discernment even among informed users (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025).

The combination of these technologies with rapid online dissemination allows fabricated narratives to enter the collective imagination as credible facts (Adriaansen & Smit, 2025). Human memory, inherently reconstructive, is exposed to stimuli optimised for familiarity and credibility—key factors in false information acceptance (Farinella, 2023). Repetition reinforces internalisation of erroneous content and increases confidence in its accuracy, hindering later correction (Hassan & Barber, 2021). Studies confirm that AI can distort existing memories and implant fictitious representations consistent with contextual cues (McAvoy & Kidd, 2024), particularly dangerous for historical and cultural knowledge transmission. Persistent exposure to AI-manipulated content thus generates epistemic insecurity by fostering doubt about previously consolidated memories (Pataranutaporn et al., 2025).

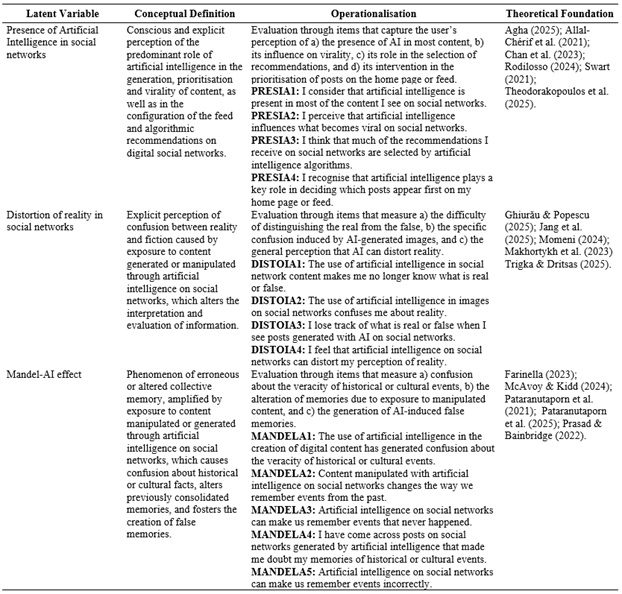

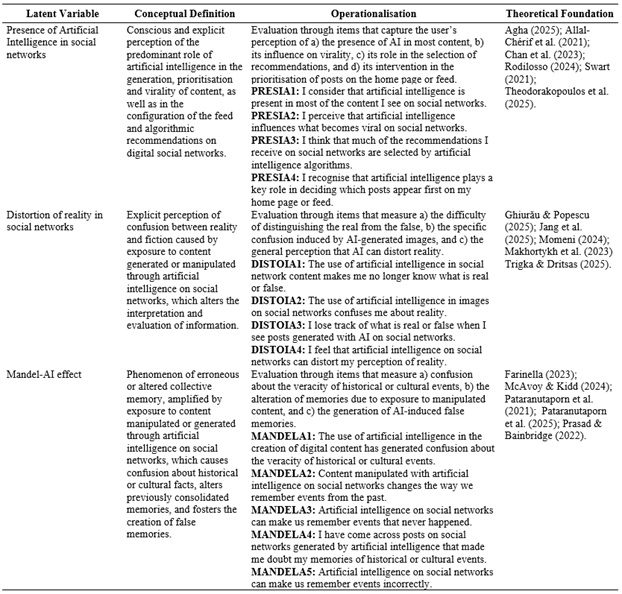

Accordingly, the “Mandel-AI Effect” is conceptualised as a contemporary extension of the Mandela Effect, where algorithmic manipulation and automated content generation trigger false or distorted memories within digital social networks. Its measurement in this study relies on five items assessing confusion about historical veracity, memory modification, and AI-induced false recollections. These, together with the other two latent variables, were conceptually defined and operationalised based on recent empirical evidence, ensuring theoretical coherence and direct alignment with the instrument’s design (see Table 1).

Table 1

Conceptual definition, operationalisation and

theoretical foundation of the instrument

The systematisation presented in Table 1 ensures traceability between the conceptual framework and the empirical indicators that make up the instrument, reinforcing its content validity. This design makes it possible to capture the complexity of each construct and to ensure that the proposed items are firmly grounded in the most recent scientific literature. In this way, the relationship between theory and measurement is strengthened, making it easier for subsequent analyses of the factorial structure and reliability of the instrument to be based on a robust conceptual foundation.

Method

This study was a quantitative and instrumental study which involved the development and verification of a psychometric instrument to evaluate the Mandel-AI Effect. The framework included theoretical design of the construct, expert validation, pilot testing, and quantitative statistical analyses of psychometric characteristics according to the standard methodology of scale validation (Carmines & Zeller, 1979).

Instrument design

For its theoretical as well as statistical validity, the instrument was formulated following a systematic process that took into consideration both form and content. Items were generated based on the theoretical framework to align latent variables with their observable indicators at the beginning of the task. Next, expert judgment and pilot testing were performed prior to the Exploratory Factor Analysis as per conventional guidelines which have emphasized that content validity is essential for the coherence and representativeness of the construct (Wilcox, 1980).

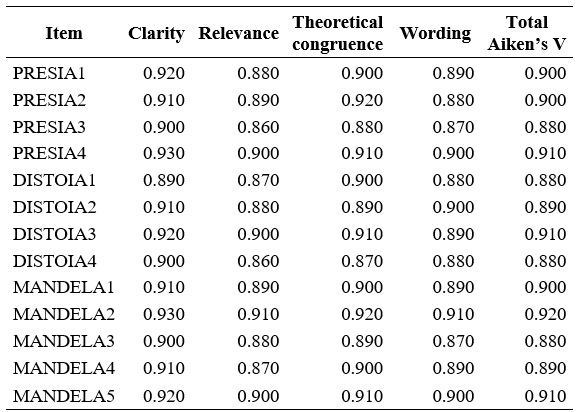

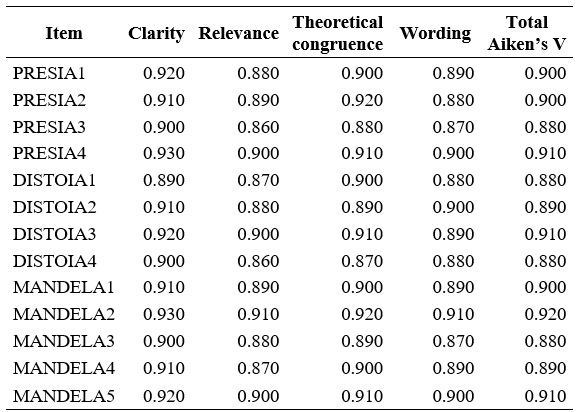

Five expert judges with postgraduate training and proven experience in psychometrics, AI, and digital social sciences participated in the content validation. Selection criteria included both domain expertise and previous involvement in instrument design. Experts evaluated each item across four dimensions (semantic clarity, content relevance, technical wording, and theoretical congruence) using a four-point ordinal scale. The level of agreement was quantified through Aiken’s V coefficient, recognised as a robust indicator of inter-judge consistency in content validity studies (Penfield & Giacobbi, 2004). All items obtained values exceeding 0.80, evidencing strong expert consensus. A summary of these indicators is presented in Table 2.

Table 2

Results

of expert judgement validation using Aiken’s V Coefficient

Note.

The values were calculated based on a 4-point ordinal scale. Aiken’s V

coefficient was used as an indicator of the level of agreement among experts.

Items with a V value greater than 0.80 were considered adequate, following

standard methodological recommendations (Penfield & Giacobbi, 2004).

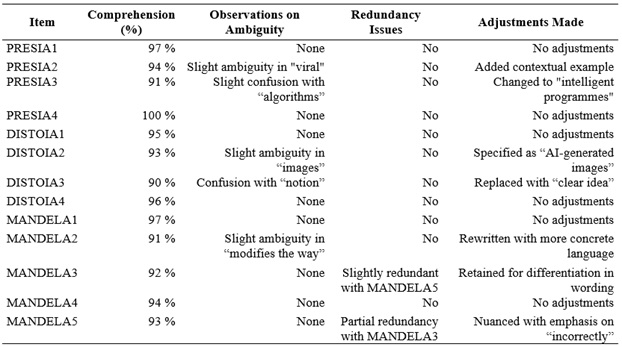

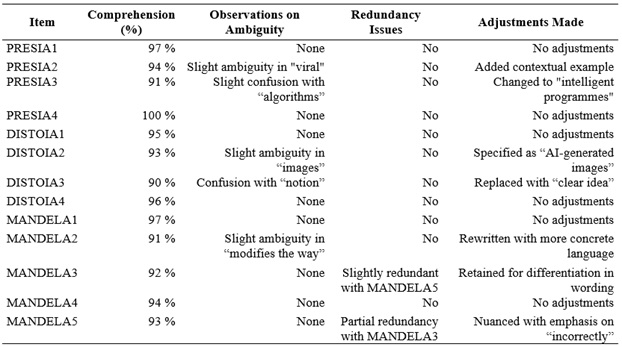

After incorporating the experts’ recommendations, a pilot test was conducted with a non-probabilistic sample of 35 active users of digital social networks, aged 18–35 years (M = 25.6; SD = 4.2), all with university-level education or higher. This phase aimed to detect potential issues of comprehension, ambiguity, or redundancy in the items and to collect preliminary data on their psychometric performance. Based on the findings, minor linguistic adjustments were made to enhance semantic precision without altering the conceptual content. The results of the pilot test are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3

Pilot

test results: Item evaluation

Note.

Percentages

indicate the level of comprehension reported by participants. Comprehension was

considered adequate if ≥ 90 % of participants understood the item without

difficulty. Adjustments focused on improving semantic clarity without altering

the theoretical content.

Following expert review and the pilot test, the instrument was subjected to an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) using the principal components method with oblique rotation (direct oblimin, Kaiser normalisation). This approach, recommended when theoretical and empirical correlations exist between dimensions, enables the identification of latent structures and the grouping of items into statistically and conceptually coherent dimensions, empirically validating the factorial structure proposed in the theoretical framework (Hair et al., 2010).

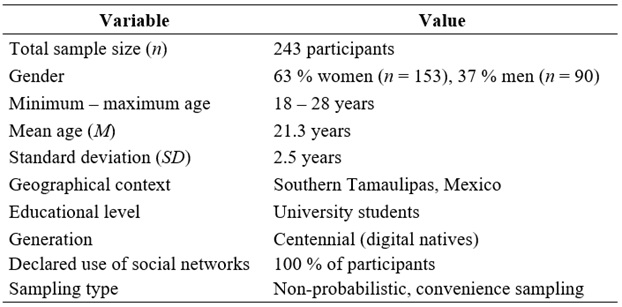

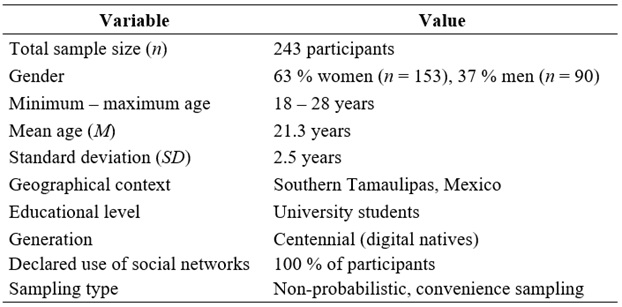

Sample

The study sample comprised 243 university students (153 women, 63 %; 90 men, 37 %), all centennials (born after 1996) enrolled in a higher education institution in southern Tamaulipas, Mexico. Participants were active users of digital social networks aged 18–28 years (M= 21.3, SD = 2.5). A student population was selected for its sociocultural homogeneity, digital fluency, and suitability for factorial analysis requiring sample normality (Comrey & Lee, 1992). As this cohort is digitally native and hyperconnected, it is especially vulnerable to algorithmic manipulation and cognitive distortion related to the Mandel-AI Effect (Salazar-Altamirano et al., 2025).

All participants were informed of the study’s objectives, the voluntary nature of participation, and confidentiality assurances. Informed consent was obtained digitally before participation, in compliance with international ethical standards for research with human subjects. Table 4 summarises the sample characteristics.

Table 4

General

characteristics of the sample

Note:

The choice of a homogeneous university sample responds to theoretical and

technical criteria that favour the stability of exploratory factorial models in

the initial stages of psychometric instrument validation (Fabrigar

et al., 1999).

In terms of statistical adequacy, the

sample size (n = 243) was determined following classical psychometric

recommendations for factor analysis, which suggest maintaining a

participant-to-item ratio between 10:1 and 20:1 to ensure stable parameter

estimation (Comrey & Lee, 1992; MacCallum et al., 1999). Given the 13 items

included in the instrument, this ratio provided a robust basis for both the

exploratory and confirmatory analyses. The achieved sample comfortably exceeds

the minimum threshold of 200 participants required for models with three or

more latent constructs and provides sufficient statistical power (β >

0.80) to detect moderate factor loadings (≥ 0.50) at α = 0.05 in

structural equation modelling. Consequently, the sample size can be considered

methodologically adequate and consistent with international standards for

psychometric validation studies.

Technique

To examine the internal structure of the instrument, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using the principal components method with oblique rotation (direct oblimin, Kaiser normalisation). This multivariate technique, recommended when correlations among factors are expected, enables the identification of latent groupings within item sets without assuming independence, thus facilitating the interpretation of underlying dimensions (Fabrigar et al., 1999). The 13-item structure was subsequently tested through a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with correlated factors, confirming the oblique nature of the model observed in the EFA. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences [SPSS Statistics] (IBM Corp., 2013), a validated tool for psychometric applications.

Continuing with the quality evaluation of the instrument, further convergent validity, discriminant validity and model fit were examined in the Analysis of Moment Structures software [AMOS] (IBM Corp., 2016). Consistent with such psychometric validation principles (Costello & Osborne, 2005), these procedures ensured the empirical robustness of the instrument prior to large-scale testing.

Before conducting the factorial analyses, statistical assumptions were examined to ensure the adequacy and robustness of the model. Normality was assessed through skewness and kurtosis indices, all of which remained within the acceptable range (|2|), and the absence of multicollinearity was confirmed using variance inflation factors (VIF < 5). The direct oblimin rotation was chosen based on theoretical expectations of correlated factors, as the constructs were conceptually interrelated within the proposed framework. Item retention criteria required communalities ≥ 0.40 and loadings ≥ 0.50, without significant cross-loadings. For the confirmatory analysis, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) was employed, supported by the sample’s adequacy (KMO > 0.80) and approximate multivariate normality verified through Mardia’s coefficient. Model fit indices were interpreted following established psychometric standards (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Tabachnick & Fidell, 2018), ensuring methodological transparency and replicability of the factorial validation process.

Instrument

The data was collected through a self-administered digital survey administered using online platforms to ensure access to the data and confirm information confidentiality. As studies of young, and heavily digital, populations, use of social media tend to be structured in this format, particularly in dealing with social media use phenomena. The instrument comprised an initial set of demographic questions (age, gender, education, and social media use), then items with respect to the three proposed scales. We used a five-point Likert-type scale (1 = “Strongly disagree,” 5 = “Strongly agree”) to measure each of the 13 items. This design, frequently used in perception and attitude research, provides simplicity, sensitivity, and interpretative simplicity for participants and researchers alike (Likert, 1932). Its ordinal structure also accounts for opinion gradients, resonating with multivariate analyses, such as exploratory factor analysis, that have been validated in psychometric research (DeVellis, 2016).

Results

The findings from the statistical validation of the instrument are presented. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted as a data reduction technique to identify the latent structure underlying the items, considering potential factor correlations. The proposed theoretical structure was subsequently evaluated using a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), where the model was tested for its fit to the observed data, evaluating both convergent and discriminant validity. Finally, internal reliability indicators and psychometric robustness evidence from both analyses are provided, confirming the instrument’s consistency, theoretical coherence, and statistical soundness for measuring the Mandel-AI Effect.

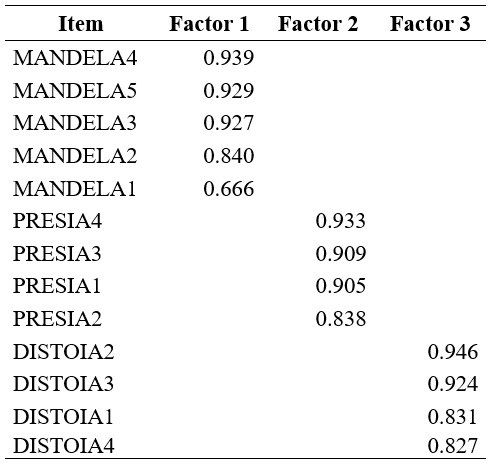

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

The exploratory factor analysis aimed to identify the dimensional structure of the 13-item instrument. Sampling adequacy was confirmed by the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of 0.925, rated “excellent” (Kaiser, 1974), while Bartlett’s test of sphericity (χ² = 3358.033, df = 78, p < 0.001) verified the suitability of the correlation matrix for factor extraction (Bartlett, 1950). All communalities exceeded 0.75 (0.751–0.878), indicating that a substantial proportion of each item’s variance was explained by the extracted factors, supporting convergent validity (Hair et al., 2010). Three components with eigenvalues above 1 were retained, jointly explaining 84.62 % of total variance—well above the 60 % threshold for robust factorial models (Costello & Osborne, 2005). Horn’s parallel analysis and the Velicer MAP test also confirmed the three-factor solution, which was further supported by Kaiser’s criterion and the scree plot, reinforcing the model’s robustness.

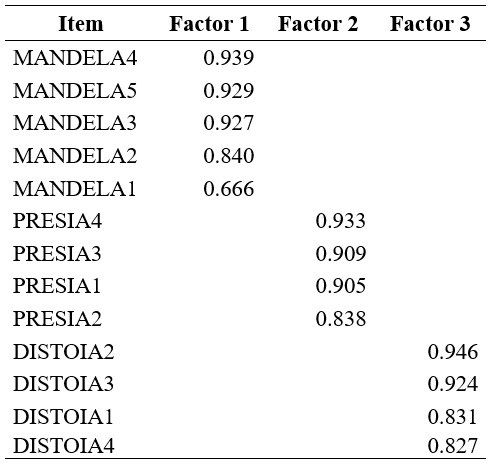

The analysis, performed using the principal components method with oblique rotation (direct oblimin, Kaiser normalisation), accounted for the theoretical and empirical correlations among dimensions. The scree plot (Cattell, 1966) revealed a sharp drop after the fourth component, confirming the three-factor structure. Inter-factor correlations (0.465–0.685) justified the oblique rotation and anticipated correlated factors in the confirmatory analysis. The rotation yielded a clear and differentiated factorial solution, maximising item loadings on their respective dimensions while minimising cross-loadings (Fabrigar et al., 1999). The pattern matrix (Table 5) showed coherent item groupings across three conceptual dimensions: Factor 1 (Mandel-AI Effect, loadings 0.666–0.939), Factor 2 (AI Presence, 0.838–0.933), and Factor 3 (Reality Distortion, 0.827–0.946). These results empirically confirm the theoretical structure and support the instrument’s structural validity (Comrey & Lee, 1992).

Table 5

Factor

loading matrix

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

As part of the instrument’s structural validation process, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using IBM AMOS (IBM Corp., 2016) with maximum likelihood (ML) estimation, after verifying compliance with the assumption of multivariate normality through Mardia’s coefficient, whose values remained within acceptable ranges. This type of analysis allows for the assessment of the degree of fit between the empirical data and the previously established theoretical structure, verifying the consistency of the measurement model through statistical indicators that estimate model fit quality, the loading of the items on their latent constructs, and the differentiation between the proposed theoretical dimensions. Due to its significant effects on psychometric studies, the inclusion of the scale is important; this adds additional rigor as it helps to verify that constructs empirically identified variables found in the exploratory analysis maintain validity through the application of covariance analysis with structured measurement (Brown, 2015). CFA results were included, and the reliability, convergent validity, discriminant validity, and overall model fit are summarized below.

The use of direct oblimin rotation was theoretically justified, as moderate intercorrelations among latent dimensions were expected based on the conceptual overlap between AI presence, reality distortion, and the generation of false memories. This approach aligns with psychometric best practices, where oblique rotations are recommended when factors are conceptually and empirically correlated rather than orthogonal (Costello & Osborne, 2005; Fabrigar et al., 1999).

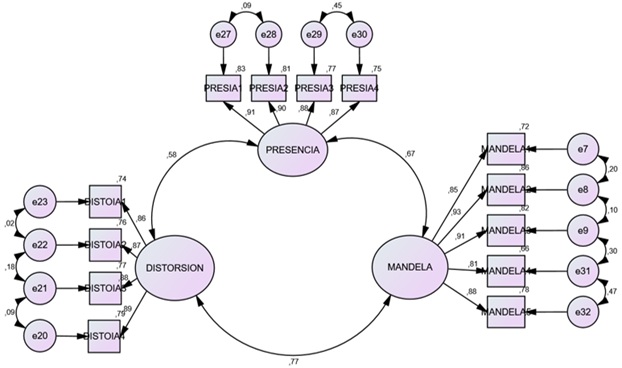

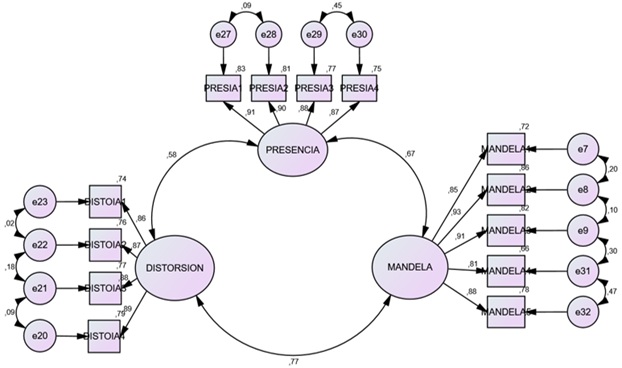

Reliability and Validity

Along with the exploratory factor analysis, a confirmatory measurement analysis was conducted in IBM AMOS (IBM Corp., 2016) with the intention of checking the convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability of each construct in the model. Such a methodical approach was important in any scale validation, as it provides empirical evidence of the consistency between the proposed items and their theoretical dimensions, thus empirically corroborating the psychometric validity of the instrument (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Hair et al., 2010). Figure 1 presents the complete structural model obtained through the confirmatory factor analysis, displaying the standardized factor loadings (λ), residual errors (θ), and inter-factor correlations. All loadings were statistically significant (p < 0.001) and exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, confirming the strong association between the observed indicators and their corresponding latent constructs. The model shows three interrelated yet distinct dimensions—Presence of AI, Distortion of Reality, and the Mandel-AI Effect—whose covariance paths reflect the theoretical assumption of partial interdependence between cognitive and perceptual processes affected by artificial intelligence (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Figure 1.

Three-factor measurement

model of the Mandel-AI effect (standardised loadings)

Figure 1.

Three-factor measurement

model of the Mandel-AI effect (standardised loadings)

Note:

Standardised

loadings (λ) and errors (θ) are reported. All p < 0.001.

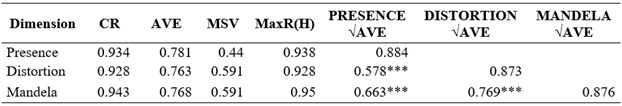

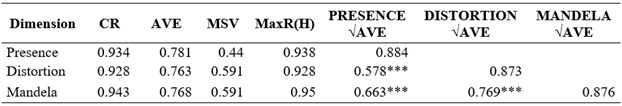

Convergent validity indicators were evaluated using two fundamental criteria: composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE), both widely recognised for their ability to estimate internal consistency and the proportion of variance explained by latent constructs (Hair et al., 2010). In all cases, the results obtained comfortably exceeded the recommended theoretical thresholds (CR > 0.70; AVE > 0.50), providing strong empirical evidence of the quality of the proposed measurement.

In detail, the CFA results maintained the three-factor structure identified in the EFA with oblique rotation. The construct Presence of AI presented a CR of 0.934 and an AVE of 0.781, suggesting that over 78 % of the total variance of its items is attributable to the underlying construct. Meanwhile, Distortion of Reality achieved a CR of 0.928 and an AVE of 0.763, values reflecting excellent internal consistency and conceptual precision in measuring AI-induced confusion. The construct Mandel-AI Effect reported the highest indicators, with a CR of 0.943 and an AVE of 0.768, reinforcing the explanatory capacity of the instrument regarding the alteration of collective memory. Complementarily, the MaxR(H) index (which estimates the maximum expected reliability for each dimension) also showed outstanding levels: Presence = 0.938, Distortion = 0.928, and Mandela = 0.950, supporting the stability and robustness of the measurement model.

In addition to the individual values of each construct, correlations among the latent variables were analysed to verify discriminant validity. The correlations were moderate and statistically significant, without compromising the conceptual independence of the factors: r = 0.578 (p < 0.001) between Presence and Distortion, r = 0.663 (p < 0.001) between Presence and Mandela, and r = 0.769 (p < 0.001) between Distortion and Mandela. All these correlations remained below the critical threshold that would compromise construct discrimination, supporting the adequate theoretical and statistical differentiation between the three proposed scales.

Finally, the maximum shared variance (MSV) values were lower than the corresponding AVE values in all cases, meeting Fornell and Larcker’s (1981) criterion for establishing discriminant validity. Table 6 below summarises the psychometric indicators of reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity for the three measured constructs.

Table 6

Psychometric

indicators: convergent validity, discriminant validity, and reliability

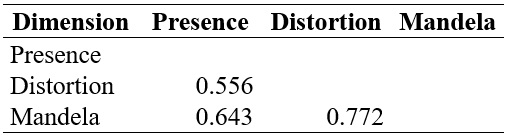

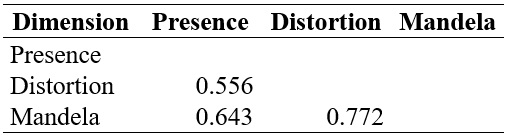

As a complement to the discriminant validity analysis using the Fornell and Larcker criterion (1981), the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) analysis was applied, which constitutes a more stringent and robust approach for determining whether the constructs assessed are empirically distinguishable from one another. This technique has been widely recommended in psychometric validation studies due to its ability to detect conceptual overlap problems that might go unnoticed with traditional methods (Henseler et al., 2015). The HTMT analysis is based on the comparison between heterotrait-heteromethod correlations (between different constructs) and monotrait-heteromethod correlations (within the same construct), providing a ratio more sensitive to the lack of discrimination.

In this study, the HTMT coefficients among the three dimensions were 0.556 between Presence and Distortion, 0.643 between Presence and Mandel-AI, and 0.772 between Distortion and Mandel-AI. All values were below the strict threshold of 0.85 suggested for confirmatory studies, which reinforces the evidence that the latent dimensions represent theoretically distinct constructs, as anticipated in the EFA through oblique rotation, with low levels of conceptual multicollinearity. This finding is relevant as it supports the discriminant validity of the instrument and its applicability for future research seeking to explore the relationship between these factors without compromising their statistical independence. Table 7 below presents in detail the HTMT coefficients obtained among the three constructs measured in the model.

Table 7

HTMT

Analysis for discriminant validity

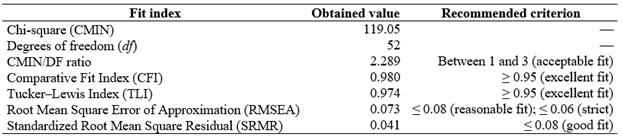

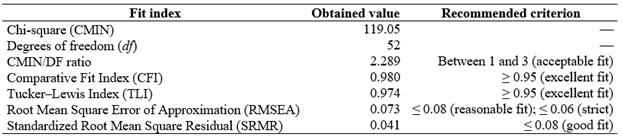

Model Fit Evaluation

In coherence with the structure identified in the EFA through oblique rotation, the results of the model were also evaluated using various global fit indices widely accepted in the psychometric and structural analysis literature. The confirmatory analysis employed the Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation method, selected for its robustness under approximate multivariate normality and its suitability for samples exceeding 200 participants (Byrne, 2016).

Firstly, the chi-square (CMIN) value was 119.05 with 52 degrees of freedom, producing a CMIN/DF ratio of 2.289, which falls within the recommended range of 1 to 3, considered adequate for well-specified models (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Likewise, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.980) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.975) both exceeded the 0.95 threshold, indicating excellent model fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA = 0.073; 90 % CI [0.059, 0.085]) reflected a reasonable approximation error for a three-factor structure with moderate sample size (Rigdon, 1996).

The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR = 0.042) further supported the model’s adequacy, remaining well below the 0.08 criterion. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC = 167.23) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC = 238.19) also supported model parsimony relative to alternative specifications. These results are summarised in Table 8, which presents the corresponding global fit indices and recommended reference values.

Table 8

Global

fit indices of the measurement model

Collectively, these indicators confirm the high quality of the model fit, complementing the previously reported evidence of internal reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Thus, the proposed instrument demonstrates excellent structural coherence and psychometric robustness for assessing the effects of artificial intelligence on perception, distortion, and the collective reconstruction of reality in digital environments mediated by social networks.

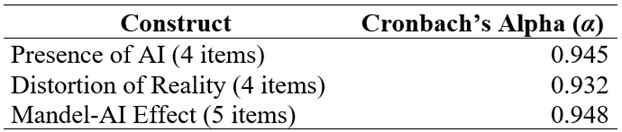

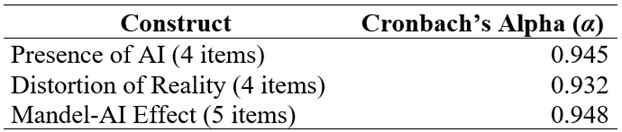

Internal reliability of

the instrument

For each construct, Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficients were estimated to supplement the model’s psychometric analysis. According to classical reliability standards, α ≥ 0.70 indicates acceptable internal consistency, while α ≥ 0.90 reflects excellent reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

The dimension Presence of AI achieved α = 0.945 (4 items), with corrected item–total correlations ranging between 0.812 and 0.855, and no improvement observed upon item removal (α if deleted = 0.931–0.940). Distortion of Reality yielded α = 0.932 (4 items), with correlations from 0.684 to 0.774 and a negligible variance in α after deletion (maximum α = 0.934; Δ ≈ 0.002). The Mandel-AI Effect dimension produced the highest internal consistency (α = 0.948; 5 items), with item–total correlations between 0.762 and 0.832, and deletion alphas ranging from 0.915 to 0.938—all values remaining below the total α, confirming the strong coherence of the subscale. These findings demonstrate excellent internal reliability across the three subscales and confirm the homogeneity of the items and their alignment with the theoretical constructs (McDonald, 1999) (see Table 9).

Table 9

Note.

Omega (ω) is not

reported in this estimation due to software limitations. However, given the

high and homogeneous factor loadings (λ ≥ 0.70) and the internal consistency

coefficients obtained (α > 0.93), it is expected that ω would yield

equivalent or slightly higher reliability estimates, as suggested in

contemporary psychometric research (McDonald, 1999; Dunn et al., 2013; Trizano-Hermosilla & Alvarado, 2016)

These results confirm that the “Mandel-AI Effect” instrument exhibits outstanding internal consistency, both at the level of each construct and in its overall measurement. The high degree of homogeneity among the items supports its statistical stability and ensures that the proposed dimensions accurately and coherently assess the theoretical phenomena underpinning them. Therefore, the scale is consolidated as a reliable psychometric tool for use in research seeking to rigorously and replicable analyse the cognitive and social impact of AI in digital environments.

Discussion and Conclusions

This research represents a watershed theoretical–methodological contribution to the domains of digital psychology and computational social science, offering empirical support for the Mandel-AI Effect concept as it expresses the complexity of how AI can shift the perception of reality and personal and collective memories in digital contexts. As digital technologies increasingly dominate social experience through automatically created, hyperrealistic, and algorithmically amplified content, the need for mechanisms to document how AI is transforming the epistemic paradigms that hold our shared certainties together has become urgent.

By executing rigorous theoretical design, expert judgment validation, and statistical analyses (exploratory factor analysis with oblimin rotation and confirmatory factor analysis), a solid psychometric instrument was established, which identified three conceptual dimensions: Presence of AI in social networks, Distortion of Reality, and the Mandel-AI Effect. Recent theoretical proposals for these dimensions (McAvoy & Kidd, 2024; Momeni, 2024; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2025) allow for a granular examination of the cognitive and affective trajectories through which AI reconfigures experience, memory, and the subjective processes of validation of reality.

Findings reveal growing users' concern about AI’s involvement in their digital environments (Swart, 2021), together with fears that such algorithmic intervention undermines individuals’ abilities to evaluate the accuracy of the content they consume (Ghiurău & Popescu, 2025) and, more alarmingly, enables artificial false memories about cultural and historical events (Pataranutaporn et al., 2021). This highlights new forms of cognitive fragility in the hyperconnected age, in which AI acts as an epistemic agent that directly intervenes in processes of memory, interpretation, and reality validation.

The validation of the factorial structure, along with high internal reliability and optimal model fit indices, confirms the internal consistency and external validity of the instrument. Moderate correlations among the factors were consistent with theoretical expectations, demonstrating the instrument’s robustness and applicability for future research exploring the psychological and social impact of AI on cognition and collective perception.

Beyond its statistical strength, the theoretical value of the Mandel-AI Effect lies in its ability to identify one of the most urgent problems of the digital era: the steady replacement of lived experience with algorithmic simulations that fabricate narratives as plausible as they are false, embedding them as truth within the collective psyche. This study therefore contributes to filling a critical methodological gap in measuring the cognitive impact of AI, opening a new area for inquiry into how digital technologies reshape collective memory and epistemic stability. Rather than being a mere example of misinformation, the phenomenon signals a structural transformation of the epistemic foundations upon which reality, truth, and shared facts are constructed.

From a broader interpretative standpoint, the findings can be further understood through the lens of distributed cognition theory (Hollan et al., 2000), which posits that cognitive processes extend beyond individual minds to include technological, social, and symbolic systems. Within AI-mediated environments, algorithms operate as epistemic agents that participate in the collective validation and distribution of knowledge, shaping how truth and memory are socially constructed. In this sense, the Mandel-AI Effect resonates with the post-truth paradigm (Lewandowsky et al., 2017), in which emotional plausibility often overrides factual accuracy in public discourse. Artificial intelligence amplifies this dynamic by producing and curating content optimized for virality and engagement rather than veracity. Consequently, digital ecosystems become arenas for the social construction of algorithmic reality (Couldry & Mejias, 2019), where mediated interactions and synthetic narratives co-create shared cognitive frameworks.

In addition, the Mandel-AI Effect can be further contextualized within the philosophy of mind, which examines how perception, memory, and consciousness are co-constituted through interactions between cognitive agents and technological environments (Chalmers, 2022; Clark, 2003). From this perspective, AI systems function as extensions of cognitive architecture, externalizing processes of attention, recall, and belief formation. Insights from the critical theory of media also reveal that digital infrastructures not only transmit information but actively shape ideological and epistemic frameworks (Horkheimer & Adorno, 2002; Zuboff, 2019), situating the Mandel-AI Effect within a wider process of cognitive commodification and algorithmic mediation of experience.

Finally, the concept aligns with recent research on epistemic trust in digital environments (Fricker, 2007; Origgi, 2018), which shows that users often rely on perceived credibility signals—such as virality or algorithmic prominence—rather than direct source verification. The erosion of epistemic trust thus reinforces the conditions under which AI-generated or manipulated content becomes internalized as collectively validated truth.

Integrating these perspectives deepens the interdisciplinary scope of the phenomenon and positions the Mandel-AI Effect as an emergent interface between cognition, media, and epistemic vulnerability in the age of artificial intelligence.

In a broader sense, the Mandel-AI Effect highlights a new cognitive–ethical frontier where artificial intelligence not only mediates perception but also participates in defining collective truth. As societies become increasingly dependent on algorithmic systems for information and memory retrieval, understanding these dynamics becomes critical for safeguarding cognitive autonomy and social trust. Thus, the implications of this research extend beyond psychometric validation toward a societal reflection on how technological infrastructures reshape epistemic norms, ethical responsibility, and the very fabric of shared reality. By providing a theoretically grounded and empirically tested tool, this study contributes to the global conversation on how to preserve human agency, truth discernment, and epistemic integrity in an age of pervasive artificial cognition.

Theoretical Boundaries and Cognitive–Ethical Implications

The Mandel-AI Effect should not be understood merely as a contemporary manifestation of the Mandela Effect amplified by artificial intelligence, but as an indicator of a deeper mutation in the relationship between human cognition and non-human informational systems. In this emergent ecology of cognition, algorithms and users co-construct meaning, memory, and epistemic trust through continuous feedback loops that blur the boundaries between organic and synthetic thought (Braidotti, 2019; Floridi, 2019).

This human–algorithmic interdependence challenges traditional notions of autonomy, perception, and belief formation. Philosophically, it suggests that cognition itself is becoming hybrid and extended, distributed across biological and computational substrates (Chalmers, 2022; Clark, 2003). Psychologically, it implies that the human mind is adapting to environments in which synthetic plausibility can supersede empirical reality, creating new cognitive conditions such as epistemic fatigue and informational dependence.

Ethically, these transformations demand reconsideration of responsibility and agency in AI-mediated epistemic environments: when truth and memory are co-constructed by human and non-human intelligences, the key question becomes not only what is remembered, but who or what participates in remembering. Recognizing these theoretical boundaries and cognitive–ethical implications strengthens the construct’s conceptual maturity and underscores its relevance for understanding the evolving nature of cognition in the algorithmic age.

Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The instrument demonstrates strong psychometric robustness; nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. The use of a non-probabilistic sample composed of centennial university students from southern Tamaulipas limits the generalisation of findings to other age groups or socio-cultural contexts. Additionally, the confirmatory factor analysis was conducted within a cross-sectional design, which restricts the capacity to explore causal or longitudinal relationships among the identified dimensions. The exclusive use of self-report measures could also introduce social desirability and subjective bias.

Future research should broaden the scope of validation by applying the scale to adolescents, older adults, and individuals with limited digital literacy to better assess varying degrees of susceptibility to AI-induced informational distortion. It is also advisable to conduct cross-cultural validations in diverse linguistic and cultural contexts to examine the measurement equivalence of the scale across countries. Such transcultural analyses would provide evidence of the universality or cultural specificity of the Mandel-AI Effect and support its international applicability in comparative research.

Longitudinal applications of the instrument are recommended to examine cumulative effects of exposure to synthetic content over time. Moreover, combining this scale with triangulated methodologies—such as digital behaviour analysis, induced recall paradigms, or neurocognitive assessment—could provide a more comprehensive and multimodal understanding of the Mandel-AI Effect.

Finally, it is recommended that future studies perform multi-group factorial invariance analyses across sociodemographic variables (e.g., gender, age, and type of social network used) to evaluate the structural stability of the instrument among subpopulations. Although such procedures exceed the scope of the present validation study, they would offer additional evidence of external validity and model robustness, thereby supporting the scale’s applicability in comparative and cross-cultural contexts (Milfont & Fischer, 2010; Putnick & Bornstein, 2016).

Furthermore, to strengthen the criterion validity of the instrument, future research could explore correlations between the Mandel-AI Effect dimensions and related constructs such as digital literacy, critical thinking, and susceptibility to misinformation. Establishing these relationships would provide empirical evidence of the instrument’s predictive and convergent power, and contribute to its practical utility in educational, psychological, and technological contexts.

Referencias

Adriaansen, R. -J., & Smit, R. (2025). Collective memory and social media. Current Opinion in Psychology, 65, 102077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2025.102077

Agha, A. M. (2025). Artificial intelligence in social media: Opportunities and perspectives. Cihan University-Erbil Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 9(1), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.24086/cuejhss.v9n1y2025.pp125-132

Allal-Chérif, O., Aránega, A. Y., & Sánchez, R. C. (2021). Intelligent recruitment: How to identify, select, and retain talents from around the world using artificial intelligence. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 169, 120822. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.120822

Anantrasirichai, N., & Bull, D. (2021). Artificial intelligence in the creative industries: A review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 55(1), 589–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10039-7

Bartlett, M. S. (1950). Tests of significance in factor analysis. British Journal of Statistical Psychology, 3(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.1950.tb00285.x

Braidotti, R. (2019). Posthuman knowledge. Polity Press.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). The Guilford Press.

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3rd ed.). Routledge.

Carmines, E. G., & Zeller, R. A. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412985642

Cattell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1(2), 245–276. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr0102_10

Chalmers, D. J. (2022). Reality+: Virtual worlds and the problems of philosophy. W. W. Norton & Company.

Chan, K. W., Septianto, F., Kwon, J., & Kamal, R. S. (2023). Color effects on AI influencers’ product recommendations. European Journal of Marketing, 57(9), 2290–2315. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejm-03-2022-0185

Clark, A. (2003). Natural-born cyborgs: Minds, technologies, and the future of human intelligence. Oxford University Press.

Comrey, A. L., & Lee, H. B. (1992). A first course in factor analysis (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315827506

Cooke, D., Edwards, A., Barkoff, S., & Kelly, K. (2024). As good as a coin toss: Human detection of AI-generated images, videos, audio, and audiovisual stimuli. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.16760. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2403.16760

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868

Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Stanford University Press.

DeVellis, R. F. (20167). Scale development: Theory and applications (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Duan, J., Yu, S., Tan, H. L., Zhu, H., & Tan, C. (2022). A survey of embodied AI: From simulators to research tasks. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence, 6(2), 230–244. https://doi.org/10.1109/tetci.2022.3141105

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2013). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12046

Erafy, A. N. E. (2023). Applications of Artificial Intelligence in the field of media. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology, 6(2), 19–41. https://doi.org/10.21608/ijaiet.2024.275179.1006

Essien, E. O. (2025). Climate change disinformation on social media: A meta-synthesis on epistemic welfare in the post-truth era. Social Sciences, 14(5), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14050304

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4(3), 272–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989x.4.3.272

Farinella, F. (2023). Artificial intelligence and the right to memory. Revistaquaestio iuris, 16(2), 976-996. https://doi.org/10.12957/rqi.2023.72636

Floridi, L. (2019). The logic of information: A theory of philosophy as conceptual design. Oxford University Press.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

Gerlich, M. (2023). Perceptions and acceptance of artificial intelligence: A multi-dimensional study. Social Sciences, 12(9), 502. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090502

Ghiurău, D., & Popescu, D. E. (20254). Distinguishing reality from AI: Approaches for detecting synthetic content. Computers, 14(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/computers14010001

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Pearson Education.

Hassan, A., & Barber, S. J. (2021). The effects of repetition frequency on the illusory truth effect. Cognitive Research Principles and Implications, 6(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00301-5

Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hollan, J., Hutchins, E., & Kirsh, D. (2000). Distributed cognition: Toward a new foundation for human-computer interaction research. ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 7(2), 174–196. https://doi.org/10.1145/353485.353487

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (2002). Dialectic of enlightenment: Philosophical fragments (E. Jephcott, Trans.). Stanford University Press

Hu, L. -T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, T. (2024). Analysis of the Mandela effect phenomenon and its propagation mechanism in the we-media era. Creativity and Innovation, 8(6), 165–170. https://doi.org/10.47297/wspciwsp2516-252726.20240806

Hussain, K., Khan, M. L., & Malik, A. (2023). Exploring audience engagement with ChatGPT-related content on YouTube: Implications for content creators and AI tool developers. Digital Business, 4(1), 100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.digbus.2023.100071

Hussein, N. EI. S. (2025). The spread of misinformation via digital platforms and its role in falsifying collective memories (Mandela Effect). The Egyptian Journal of Media Research, 2025(90), 405-475. https://doi.org/doi: 10.21608/ejsc.2025.405911

IBM Corp. (2013). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 22). IBM Corp.

IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS AMOS for Windows (Version 24). IBM Corp.

Ienca, M. (2023). On artificial intelligence and manipulation. Topoi, 42(3), 833–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-023-09940-3

Jang, E., Lee, H. M., Lee, S., Jung, Y., & Sundar, S. S. (2025). Too good to be false: How photorealism promotes susceptibility to misinformation. CHI EA '25: Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Japan, 531, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706599.3719796

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39(1), 31–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02291575

Knell, M. (2021). The digital revolution and digitalized network society. Review of Evolutionary Political Economy, 2(1), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-021-00037-4

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., & Cook, J. (2017). Beyond misinformation: Understanding and coping with the “post-truth” era. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 6(4), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2017.07.008

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 22 140, 55.

Lu, W. (2024). Inevitable challenges of autonomy: ethical concerns in personalized algorithmic decision-making. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03864-y

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

MacLin, M. K. (2023). Mandela Effect. In M. K. MacLin (Eds.), Experimental design in psychology: A case approach (pp. 267–288). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003378044-20

Makhortykh, M., Zucker, E. M., Simon, D. J., Bultmann, D., & Ulloa, R. (2023). Shall androids dream of genocides? How generative AI can change the future of memorialization of mass atrocities. Discover Artificial Intelligence, 3(1), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44163-023-00072-6

Matei, S. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence and collective remembering. The technological mediation of mnemotechnic values. Journal of Human-Technology Relations, 2(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.59490/jhtr.2024.2.7405

McAvoy, E. N., & Kidd, J. (2024). Synthetic hHeritage: Online platforms, deceptive genealogy and the ethics of algorithmically generated memory. Memory Mind & Media, 3, e12. https://doi.org/10.1017/mem.2024.10

McDonald, R. P. (1999). Test theory: A unified treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.857

Momeni, M. (2024). Artificial intelligence and political deepfakes: Shaping citizen perceptions through misinformation. Journal of Creative Communications, 20(1), 41-56. https://doi.org/10.1177/09732586241277335

Muralidhar, A., & Lakkanna, Y. (2024). From clicks to conversions: Analysis of traffic sources in E-Commerce. arXivpreprint arXiv:2403.16115. https://doi.org/10.48550/arxiv.2403.16115

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

Origgi, G. (2018). Reputation: What it is and why it matters. Princeton University Press.

Pataranutaporn, P., Archiwaranguprok, C., Chan, S. W. T., Loftus, E., & Maes, P. (2025). Synthetic human memories: AI-edited images and videos can implant false memories and distort recollection. CHI '25: Proceedings of the 2025 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Japan, 538, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713697

Pataranutaporn, P., Danry, V., Leong, J., Punpongsanon, P., Novy, D., Maes, P., & Sra, M. (2021). AI-generated characters for supporting personalized learning and well-being. Nature Machine Intelligence, 3(12), 1013–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-021-00417-9

Penfield, R. D., & Giacobbi, P. R., Jr. (2004). Applying a score confidence interval to Aiken’s item Content-Relevance Index. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 8(4), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327841mpee0804_3

Prasad, D., & Bainbridge, W. A. (2022). The visual Mandela effect as evidence for shared and specific false memories across people. Psychological Science, 33(12), 1971–1988. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221108944

Purnama, Y., & Asdlori, A. (2023). The role of social media in students’ social perception and interaction: Implications for learning and education. Technology and Society Perspectives (TACIT), 1(2), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.61100/tacit.v1i2.50

Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

Rigdon, E. E. (1996). CFI versus RMSEA: A comparison of two fit indexes for structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling a Multidisciplinary Journal, 3(4), 369–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519609540052

Rodilosso, E. (2024). Filter bubbles and the unfeeling: How AI for social media can foster extremism and polarization. Philosophy & Technology, 37(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00758-4

Rüther, M. (2024). Why care about sustainable AI? Some thoughts from the debate on meaning in life. Philosophy & Technology, 37(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-024-00717-z

Salazar-Altamirano, M. A., Martínez-Arvizu, O. J., Galván-Vela, E., Ravina-Ripoll, R., Hernández-Arteaga, L. G., & Sánchez, D. G. (2025). AI as a facilitator of creativity and wellbeing in business students: A multigroup approach between public and private universities. Encontros Bibli Revista Eletrônica De Biblioteconomia E Ciência Da Informação, 30, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2025.e103485

Shanmugasundaram, M., & Tamilarasu, A. (2023). The impact of digital technology, social media, and artificial intelligence on cognitive functions: A review. Frontiers in Cognition, 2, 1203077. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcogn.2023.1203077

Sireli, O., Dayi, A., & Colak, M. (2023). The mediating role of cognitive distortions in the relationship between problematic social media use and self-esteem in youth. Cognitive Processing, 24(4), 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-023-01155-z

Spring, M., Faulconbridge, J., & Sarwar, A. (2022). How information technology automates and augments processes: Insights from Artificial‐Intelligence‐based systems in professional service operations. Journal of Operations Management, 68(6–7), 592–618. https://doi.org/10.1002/joom.1215

Sun, Y., Sheng, D., Zhou, Z., & Wu, Y. (2024). AI hallucination: towards a comprehensive classification of distorted information in artificial intelligence-generated content. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03811-x

Swart, J. (2021). Experiencing algorithms: How young people understand, feel about, and engage with algorithmic news selection on social media. Social Media + Society, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051211008828

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (20189). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Pearson.

Theodorakopoulos, L., Theodoropoulou, A., & Klavdianos, C. (2025). Interactive viral marketing through big data analytics, influencer networks, AI integration, and ethical dimensions. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 20(2), 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/jtaer20020115

Torous, J., Bucci, S., Bell, I. H., Kessing, L. V., Faurholt‐Jepsen, M., Whelan, P., Carvalho, A. F., Keshavan, M., Linardon, J., & Firth, J. (2021). The growing field of digital psychiatry: Current evidence and the future of apps, social media, chatbots, and virtual reality. World Psychiatry, 20(3), 318–335. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20883

Trigka, M., & Dritsas, E. (2025). The evolution of Generative AI: Trends and applications. IEEE Access, 13, 98504-98529. https://doi.org/10.1109/access.2025.3574660

Trizano-Hermosilla, I., & Alvarado, J. M. (2016). Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 769. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769

Wilcox, R. R. (1980). Some results and comments pn using latent structure models to measure achievement. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 40(3), 645–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448004000308

Williamson, S. M., & Prybutok, V. (2024). The era of Artificial Intelligence deception: unraveling the complexities of false realities and emerging threats of misinformation. Information, 15(6), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/info15060299

Wu, X., Zhou, Z., & Chen, S. (2024). A mixed-methods investigation of the factors affecting the use of facial recognition as a threatening AI application. Internet Research, 34(5), 1872–1897. https://doi.org/10.1108/intr-11-2022-0894

Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books.

Notes

*

Research article.

Author notes

a Correspondence author. Email: mario_salazar_altamirano@hotmail.com

Additional information

How to cite: Rangel-Lyne, L., & Salazar-Altamirano, M. A. (2025). Mandel-AI Effect:

Proposed measurement of the Mandela Effect induced by artificial intelligence

in digital social networks. Universitas Psychologica,

24, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy24.maie