The global prevalence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents is estimated at 7–8%, with boys about two to three times more likely to be diagnosed than girls; worldwide, the combined presentation is most common, followed by the inattentive and, less frequently, the hyperactive–impulsive type (Wang et al., 2025). Rates are higher in high- and upper-middle-income regions such as North America and Australasia and lower in settings with a low Socio-demographic Index, where underdiagnosis is likely (Ayano et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2025). In Latin American and Caribbean countries (LACCs), school-based studies report prevalences ranging from 7–10% in Brazilian and Panamanian samples to around 9–10% in Argentina and Chile and 16–20% in Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador, where marked executive, memory, language, and academic deficits have also been documented (De la Barra et al., 2015; Fleitlich-Bilyk et al., 2004; Gallardo-Saavedra et al., 2019; Landínez-Martínez et al., 2025; Michanie et al., 2007; Pineda et al., 2001; Salari et al., 2023; Vélez-Calvo et al., 2024). ADHD rarely presents in isolation. A recent systematic review (Njardvik et al., 2025) found that 66.5% of children and adolescents with ADHD met criteria for at least one additional psychiatric disorder, most often oppositional defiant, other behavior, and anxiety disorders, with several other conditions also elevated relative to the general population. These comorbidities intensify core symptoms, increase functional impairment, and highlight the need for comprehensive, integrated interventions (Drechsler et al., 2020).

Considering these multifaceted challenges, new frameworks are reshaping how ADHD is conceptualized and treated. The neurodiversity paradigm understands ADHD as a natural cognitive variation rather than a deficit, emphasizing strengths and environments that support well-being (Dwyer, 2022). In parallel, epistemologies of care critique the medicalization of neurodevelopmental conditions and promote relational, ethical, and community-rooted practices, which are particularly relevant in LACCs informed by decolonial and community-based perspectives (Unda Villafuerte et al., 2023). Within this landscape, growing skepticism toward pharmacological dominance—given that medication prioritizes symptom suppression, is not universally effective, and may be especially limited for younger children or those with comorbidities—has fueled interest in psychosocial and neuropsychological interventions that address executive functioning, emotion regulation, and parenting processes (Sibley et al., 2023; Wilens et al., 2024).

Building on these conceptual developments, current guidelines increasingly emphasize comprehensive, multimodal approaches that translate these principles into everyday practice. Given ADHD’s broad impact on daily functioning, interventions that coordinate supports across family and school contexts and actively engage parents and teachers as key agents of change are particularly promising (Lambek et al., 2023; Van der Oord & Tripp, 2020). Behavioral Parent Training (BPT) remains the most widely used non-pharmacological approach for preschool- and elementary-aged children, with robust evidence for reducing symptoms and behavioral problems and improving parenting skills and parent–child relationships (Doffer et al., 2023; Marquet-Doléac et al., 2024). However, the scope of these interventions must also encompass the psychosocial toll ADHD places on families: parents report markedly lower quality of life and elevated stress that may heighten the risk of harsh parenting, while many programs still overlook strategies to foster parental emotion regulation and stress management (Leitch et al., 2019; McAloon & de la Poer Beresford, 2023).

Moreover, questions remain about the durability of BPT’s benefits. Although BPT shows short-term effectiveness in reducing ADHD-related behavior problems, its long-term impact is often limited (Doffer et al., 2023). One explanation is that it insufficiently targets core neurocognitive deficits such as working memory, inhibitory control, and sustained attention, which are linked to frontoparietal and fronto-basal ganglia dysfunction (Drechsler et al., 2020). Emerging evidence indicates that interventions combining behavioral and neurocognitive components yield more robust and sustained outcomes; for example, pairing BPT with cognitive or neuropsychological training (e.g., working memory training) produces greater gains in executive functioning than behavioral strategies alone (Chacko et al., 2018; Lambek et al., 2023; Wilens et al., 2024). Such multimodal approaches may more effectively address both observable symptoms and underlying cognitive deficits, enhancing immediate and long-term functioning in youth with ADHD.

To meet this challenge, it is crucial to design parent-focused intervention programs that address these dual needs, particularly in regions where service access is limited. For such interventions to be effective and scalable, they must also overcome common barriers to participation, including time constraints, geographic isolation, and inflexible program schedules (McAloon & de la Poer Beresford, 2023). Asynchronous and virtual parent training programs represent a promising solution. Studies suggest these digital formats are not only comparable to face-to-face interventions in their outcomes but also more accessible for families facing logistical constraints, with documented benefits for children’s behavioral and emotional problems and caregivers’ psychological well-being (Galvin et al., 2024; Thongseiratch et al., 2020).

Nonetheless, a significant research gap persists. Despite their promise, few virtual interventions have integrated all the essential elements for comprehensive ADHD management—such as psychoeducation, emotional regulation, stress management, behavioral strategies, and neuropsychological training. This gap is especially pronounced in LACCs, where culturally adapted, scalable models remain limited (Gerdes et al., 2021). Bridging this divide will require the development of context-sensitive programs that overcome structural barriers and engage participants using relatable, linguistically and culturally relevant materials (e.g., Paiva et al., 2024).

In response to this need, the present study aims to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of an asynchronous behavioral and neurocognitive training program tailored for parents of children with ADHD in a LACC, specifically Colombia. Building on evidence that ADHD interventions must address both behavioral and neuropsychological dimensions, this program integrates psychoeducation, emotional regulation, and executive-functioning support. Acceptability is examined as the extent to which participants and implementers perceive the intervention as relevant, appropriate, and beneficial, whereas feasibility focuses on the practicality of delivering asynchronous modules under real-world conditions, including resource limitations and diverse family contexts. Additionally, the study explores the program’s preliminary effects on parenting stress, ADHD symptomatology, and children’s behavioral challenges. By addressing key emotional, cognitive, and contextual factors—often overlooked in existing models—this research seeks to advance culturally responsive, scalable interventions for families affected by ADHD in the LACC region.

Method

Participants, design, and setting

The study used a convenience sample of 10 parents—seven mothers and three fathers—of children with ADHD from various cities in Colombia, recruited through the primary researchers’ networks. Due to time constraints, data collection began after one month of recruitment with these 10 participants. Parent inclusion criteria were: (a) age over 18 years, (b) at least a high school education, (c) reliable internet access, and (d) access to Zoom via a desktop computer, laptop, or tablet with a video camera. Children were required to: (a) be 7–10 years old, (b) have an ADHD diagnosis made by a certified neuropsychologist, (c) score above 11 on the Problem Scale and above 70 on the Intensity Scale of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI), and (d) be currently enrolled in school.

This study employed a complementary design, combining a quantitative pretest–posttest structure with a qualitative component grounded in phenomenological inquiry. This mixed approach allowed for an integrated examination of preliminary outcomes and the lived experiences of parents navigating parenting stress, behavioral challenges, and ADHD symptomatology in the Colombian context. A phenomenological perspective was chosen to explore how parents make sense of their caregiving roles and emotional experiences, illuminating the subjective meanings they assign to their realities (van Manen, 2023). Thematic analysis followed Braun and Clarke’s (2013) six-phase method, with analytic decisions informed by phenomenological principles to preserve the depth and contextual nuance of participants’ accounts.

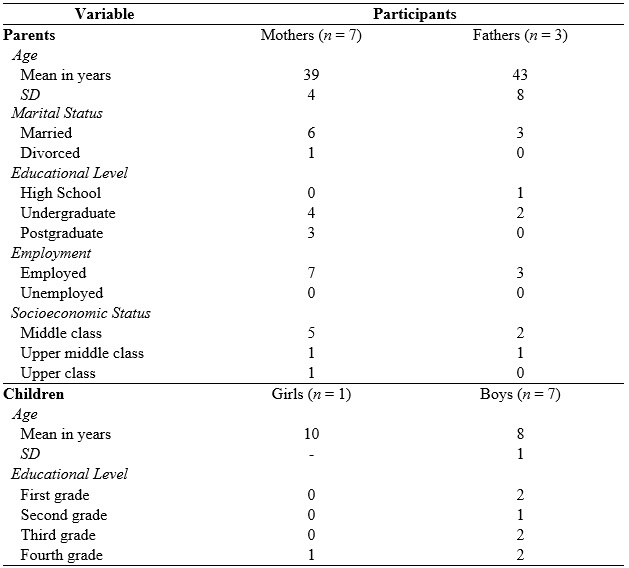

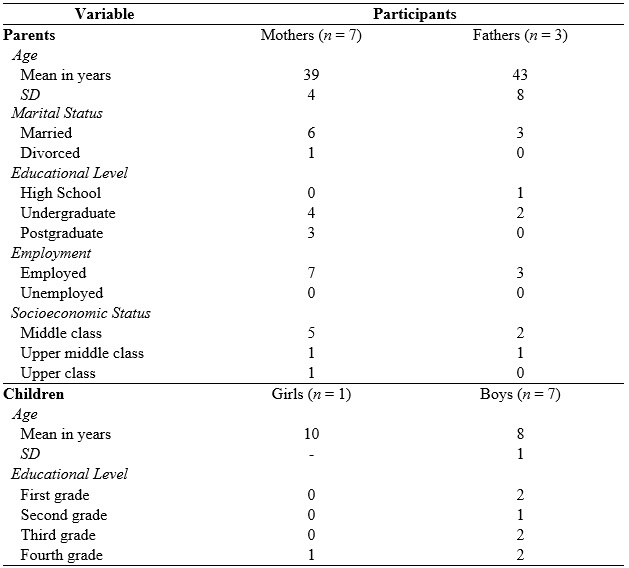

Detailed demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. Participants 1 (mother) and 2 (father), 3 (mother) and 4 (father), and 5 (mother) and 6 (father) were each parent of a single child, while one participant (P10) had twins—a girl and a boy—both diagnosed with ADHD. The study was approved by the university’s ethics committee, and all parents provided informed consent. Because the children were indirect beneficiaries of the intervention and considered secondary participants, informed assent was not obtained from them.

Table 1

Demographic data of

participating parents and children

Note.

SD = Standard

deviation.

The study was conducted entirely via videoconferencing using HIPAA-compliant Zoom™, with procedures designed to protect participant confidentiality. Before each module, the three authors and two research assistants met virtually with participants to address any challenges from the previous module and to outline the content and objectives of the next one.

Primary Outcomes

Parental Stress Index – Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995)

The PSI-SF is a 36-item abbreviated version of the full scale that yields a Total Stress (TS) score across three dimensions: Parental Distress (PD), Difficult Child (DC), and Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI). Items are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except for items 22 and 33, which use alternative formats. Higher scores indicate greater parenting stress, with scores at or above the 90th percentile (114/115) considered clinically significant (Abidin, 1995). The Spanish adaptation used in this study (Rivas et al., 2021) has shown strong internal consistency (McDonald’s omega = .84–.94; Cronbach’s alpha = .79–.93) and high convergent and diagnostic validity.

Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (ECBI; Eyberg & Pincus, 1999)

The ECBI is a 36-item parent-report tool assessing disruptive behaviors in children aged 2 to 16 years. It includes two scales: the Intensity Scale, rating behavior frequency on a 7-point Likert scale (1 "never" to 7 "always"), and the Problem Scale, determining if a behavior is problematic with a yes/no format. The ECBI has high internal consistency (Problem Scale: 0.91, Intensity Scale: 0.93), and validity in distinguishing between clinical and non-clinical populations (Rich & Eyberg, 2001). This study used a validated Spanish translation (Fernández de Pinedo, 1998).

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale–Fourth Version (SNAP-IV)

The SNAP-IV includes 26 items evaluated on a 4-point scale from 'not at all' to 'very much', divided into three subscales: Inattention (nine items), Hyperactivity/ Impulsivity (nine items), and Oppositional (eight items). Subscale scores are obtained by averaging the item scores. The Inattention and Hyperactivity/Impulsivity subscales can be combined for a combined ADHD score, indicating symptom severity (Bussing et al., 2008). Higher scores indicate greater symptomatic behaviors. This study used a Spanish-adapted version of the SNAP-IV (Grañana et al., 2011).

Rubric for Satisfaction with Modules

The self-evaluation rubric for satisfaction with modules assessed five key criteria: Purpose, Clarity, Usefulness, Interest, and Satisfaction. This rubric was administered at the end of the focus group. Each criterion was rated on a scale from 1 (Insufficient) to 4 (Excellent), evaluating how well the videos' purpose was understood, the clarity of the language used, the perceived usefulness of the content for managing ADHD, the viewer's interest and engagement, and overall satisfaction with the content, format, and quality of the videos.

Parent’s Consumer Satisfaction

Questionnaire (PCSQ; McMahon & Forehand, 2003)

A

modified version of the PCSQ was used to measure parental satisfaction with the

training program at post-assessment. The questionnaire consists of 47

questions, distributed across several dimensions: overall program, teaching

format, specific parenting techniques, therapist performance during the

training process, and general opinions on changes made, progress, outcomes, and

the management of children's problem behaviors. Responses are recorded on a

Likert scale ranging from 1 ("considerably worse") to 7 ("considerably

better"), with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction.

Procedure

This study was conducted in multiple phases. First, two neuropsychology experts (second and third authors) and one behavior analyst (first author) developed five modules for parents of children with ADHD, drawing on seminal and empirical work by Chronis-Tuscano et al. (2020), McMahon and Forehand (2003), Zelazo (2020), and Whittingham and Coyne (2019). The content included behavioral management techniques—such as timeout, token economies, reinforcement procedures, analysis of antecedents and consequences, emotional validation, and mindfulness—shown to reduce ADHD symptoms and parental stress (Doffer et al., 2023; Hornstra et al., 2023; Marquet-Doleac et al., 2024). In line with neuropsychological research, the modules also incorporated training of executive functions (attention, inhibition, self-regulation, and concentration) to improve ADHD-related neuropsychological functioning (Chacko et al., 2018; Kofler et al., 2018; Lambek et al., 2023).

The modules were then reviewed by two expert judges for clarity, coherence, relevance, and sufficiency. Following their feedback, the materials were digitized by an educational company and underwent three rounds of revision. For the pilot study, participants provided informed consent and completed the PSI-SF, ECBI, and SNAP-IV via REDCap; participant P10, who had twins with ADHD, completed one PSI-SF and two ECBI and SNAP-IV forms (one per child). After the pretest, parents engaged with one training module per week, each introduced by a one-hour meeting to address questions and challenges. Upon completion, participants repeated the initial questionnaires and completed a satisfaction survey. One week later, a two-hour focus group was held to gather qualitative feedback on the modules’ purpose, clarity, utility, interest, satisfaction, and relevance, which was evaluated using a six-item rubric developed for this study.

Training Modules

The intervention program, "Living with ADHD as a Family," comprised five modules aimed at equipping parents with practical tools for managing ADHD in their children. The modules covered a comprehensive examination of the disorder, including foundational understanding and strategic approaches to mitigating parental stress. They included behavioral management, self-regulation techniques for children, strategies to enhance attention, and the promotion of healthy habits. Each module was designed to improve the well-being and development of children with ADHD. Participants accessed each module for one week, engaging with interactive content such as videos, quizzes, and activities.

Module 1: Understanding ADHD Fundamentals

This module served as an instructive primer on ADHD, elucidating its basic characteristics and dispelling myths. It included a 10-minute video about everyday challenges parents face, a 15-minute simulation exercise, "A Day in Santiago’s Shoes," and a session defining ADHD, discussing its challenges, subtypes, and etiology, with a focus on executive functions.

Module

2: Navigating Parental Stress

This module provided parents with strategies for managing stress, focusing on the unique challenges of parenting. It covered causes of stress, their impact on mental health, and methods to address stress triggers. It included guidance on measuring stress levels, validating emotions, using strategies to regulate emotions, and introduced mindfulness practices through interactive exercises.

Module 3: Behavioral Management Techniques

This module equipped parents with tools to encourage socially appropriate behaviors in their children. It included detailed knowledge about child behavior, the use of consequences, setting clear household rules, and reducing challenging behaviors. It covered reinforcement principles and provided practical tools for observing and encouraging good behavior while reducing negative behaviors.

Module 4: Enhancing Self-Regulation

This module focused on strategies to strengthen children's self-regulation, influencing their behavior and long-term emotional well-being. It included concepts such as executive functions and self-control, paired with practical tools and exercises to guide children in managing their emotions and behavior. Strategies included self-instruction techniques, emotional regulation methods, relaxation exercises, decision-making, and mindfulness practices.

Module 5: Attention and Concentration Skills and Healthy Habits

This final module provided parents with strategies for teaching internal strategies and environmental adaptations. It focused on encouraging healthy habits by improving school routines, sleeping patterns, and eating habits. It aimed to enhance children’s attention and concentration by establishing consistent, healthy eating and sleeping schedules, increasing physical activity, and making study time more efficient.

Posttest and Focus Group

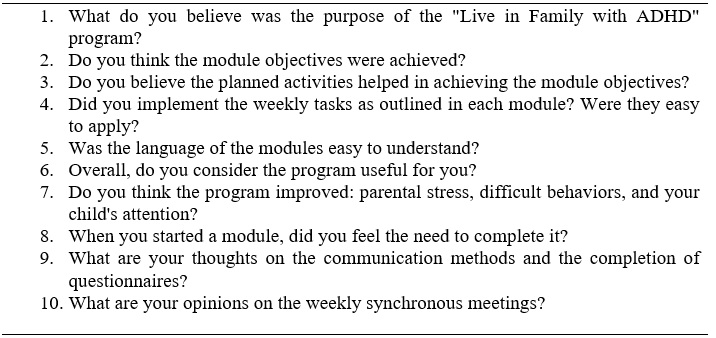

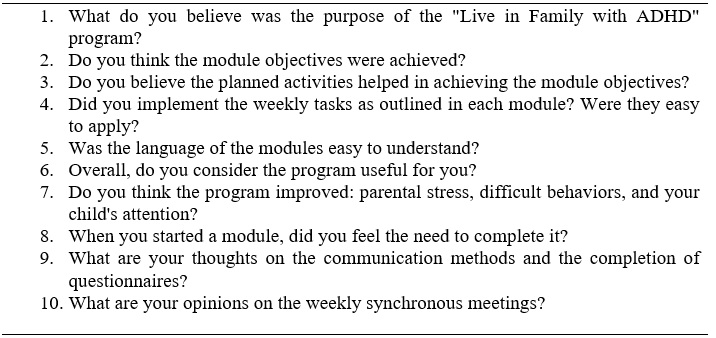

The posttest was administered immediately after participants completed the fifth module. Measures included the PSI-SF, ECBI, SNAP-IV, and Parent’s Consumer Satisfaction Questionnaire. A three-hour focus group with nine participants was conducted one week after the study ended. A semi-structured interview explored four general themes: (1) acceptability and appropriateness of program materials, delivery, and key components; (2) barriers to participation and engagement; (3) observed changes in parenting practices; and (4) child behavior at home. Table 2 presents the questions asked during the focus group.

Table 2

Focus group questions

Data Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses to examine changes in parenting stress, children’s problem behaviors, and ADHD symptoms. Given the small sample, we used the Reliable Change Index (RCI; Jacobson & Truax, 1991) to determine whether pre–post differences exceeded measurement error, classifying participants as showing improvement, no change, or deterioration. Although the RCI has limitations—such as reduced sensitivity to subtle but meaningful change and a risk of false negatives—it remains a practical tool in early-phase studies with small samples and only two assessment points; as McAleavey (2024) notes, it offers a useful heuristic for identifying individual-level change when more sophisticated analyses are not feasible.

For the qualitative component, we adopted an inductive, realist approach, treating participants’ accounts as accurate reflections of their lived experiences. We conducted reflexive thematic analysis following Braun and Clarke’s (2013) six-phase framework: (1) familiarizing with the data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) developing themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) writing the report. Coding was data-driven, with units defined as meaningful segments capturing participants’ experiences, interpretations, and emotional responses related to parenting stress, child behavior, and ADHD symptom management. Initial codes were generated inductively, refined through iterative comparison, and grouped into broader themes based on conceptual similarity; thematic saturation was considered reached when no new codes emerged from the final transcripts.

All coding was conducted manually to maintain close engagement with the data. To enhance credibility and confirmability, two researchers (assisted by two research assistants) independently coded the transcripts, resolved discrepancies through discussion, and developed a working codebook. Under the supervision of the lead researchers, themes were further refined using AI-assisted analysis with ChatGPT., a tool increasingly validated in qualitative research (Tai et al., 2024; Wachinger et al., 2024). Finally, we conducted member checking by sharing a summary of preliminary themes with a subset of participants and integrating their feedback into the refinement process.

Results

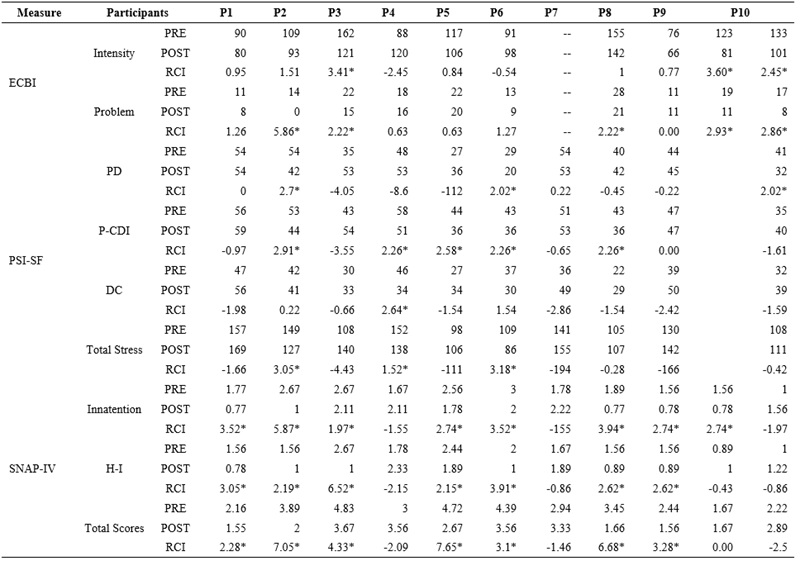

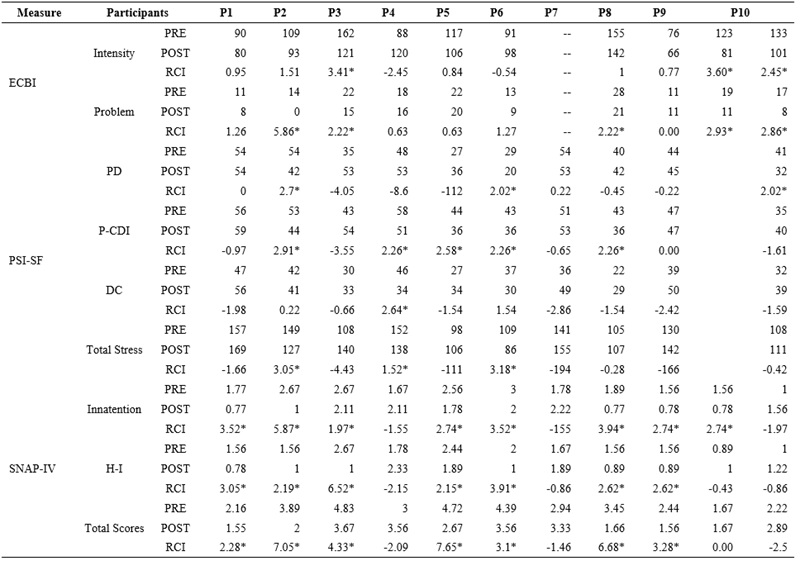

Outcome Measures and RCI

Table 3 presents the ECBI results. Data for P7 is missing as the participant did not attend the posttest session for personal reasons, and P10 has two scores for her daughter and son. Significant changes were observed in the Intensity and Problem scales. Participants 3 (RCI=3.41) and 10 (both children; RCI=3.60 and RCI=2.45) reported clinically significant decreases in the Intensity Scale, indicating a reduction in disruptive behaviors below the clinical threshold of 131. In the Problem Scale, significant reductions were noted for Participants 2, 3, 8, and 10 (both children), with RCI values of 5.86, 2.22, 2.22, 2.93, and 2.86, respectively, indicating a decrease in problematic behaviors below the clinical threshold of 15.

Table 3

Pretest, posttest, and reliable change index scores for all participants

Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Table 3) show significant changes in parental stress levels. Participant 10 reported one PSI score for both children. Notably, Participants 2 (RCI=2.70), 6 (RCI=2.02), and 10 (RCI=2.02) reported significant improvements in the Parental Distress subscale. Significant amelioration in the Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction subscale was observed in Participants 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8 with RCI values of 2.91, 2.26, 2.58, 2.26, and 2.26, respectively. Additionally, Participant 4 indicated improvements in the Difficult Child subscale, with an RCI value of 2.64. Total Stress scores decreased significantly for Participants 2 (RCI = 3.05), 4 (RCI = 1.52) and 6 (RCI=3.18).

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale–Fourth Edition (SNAP-IV; bottom row of Table 3) shows participant 10 completed two SNAP-IV questionnaires, one for each child. Participants 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, and Participant 10 (daughter) reported significant reductions in Inattention, with RCI values of 3.52, 5.87, 1.97, 2.74, 3.52, 3.94, 2.74, and 2.74. Six participants indicated significant reductions in Hyperactivity/Impulsivity scores, P1 (RCI=3.05), P2 (RCI=2.19), P3 (RCI=6.52), P5 (RCI=2.15), P6 (RCI=3.91), P8 and P9 (RCI=2.62 each). Total ADHD scores showed an overall significant decrease in ADHD symptoms for Participants 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9 (see Table 3 for RCIs).

Parent’s Consumer

Satisfaction Questionnaire

Results showed that most parents found the program effective in managing their children's behavioral issues and reducing their stress levels. Specifically, 70% of parents observed considerable improvements in their children's behavior, while 30% noted minor but positive changes. Post-intervention satisfaction was high, with 70% of parents satisfied and 30% very satisfied, suggesting the program exceeded expectations by positively influencing both personal and family life.

The intervention enhanced parents' confidence in handling ADHD, with many reporting feeling better prepared to address current and future challenges associated with the disorder. Ninety percent of participants rated their experience with the program modules positively, reflecting well on the quality of the content and delivery. Instructional methods were deemed clear and understandable, with 30% finding the program extremely easy to engage with, indicating a successful pedagogical design. However, some feedback suggested minor enhancements to the home practice components, despite 90% finding these easy to implement.

Most participants found the practical application of the program's techniques and strategies straightforward. Nonetheless, there were calls for improvements in specific areas such as "Time Out" and "Token Economy," where experiences ranged from easy to neutral. Parents suggested reducing the number of techniques to allow more practice time for each, which could enhance both effectiveness and user satisfaction.

In terms of program delivery, the researchers received high praise for their teaching skills and preparedness, with 90% of participants rating them as superior. Participants preferred modules focusing on parental stress and specific techniques from modules 2 and 3, including mindfulness practice, emotional validation, self-care skills, and strategies for managing problem behaviors, such as establishing routines and reinforcement procedures. These elements were highlighted for their practical benefits. For future iterations of the program, it is recommended to increase interactivity and streamline the content to facilitate easier access.

Evaluation of the Acceptability of Intervention Modules

Rubric Results

The rubric completed by parents indicated that the modules content was easy to understand and highly relevant for managing their children’s ADHD. Most participants awarded an “Excellent” rating for content and communication quality, highlighting its effectiveness, while a few “Good” ratings suggested minor refinements to improve coherence. Participants also highly valued the practical utility of the videos, reported active use of the strategies, and expressed willingness to recommend the resources to other parents, reflecting strong engagement and interest. Overall, parents rated the content, format, and quality of the videos very positively, with only two “Good” satisfaction ratings pointing to small improvements in format or visual elements; all participants emphasized the material’s practical and theoretical relevance for day-to-day ADHD management.

Textual Analysis of Focus Group Responses

The focus group results revealed six themes reflecting parents' perceptions of the "Living with ADHD as a Family" program. These themes include integrating ADHD management into daily life, empowerment through ongoing education, adapting strategies to individual needs, and more. Below is a discussion on how these themes influenced the experiences of the parents and children involved, providing insights for future implementation.

Integration and Understanding of ADHD in Family and Educational Environments

The results highlight the importance of coordinated strategies between family and school environments. Consistent management strategies were essential for enhancing life quality for both children and their families. One mother shared, "Addressing activities separately initially allowed us to unify visions and establish agreements before moving forward together." Another noted, "We recommended some of the strategies learned to our children’s teachers."

Empowerment through Information and Ongoing Education

Empowerment emerged as participants discussed the value of the program's information. This information provided both knowledge and practical guidance for managing ADHD at home. One father explained, "Understanding each concept covered in the modules meant achieving a goal," highlighting the role of theoretical understanding in their empowerment. Another mother shared, "What's important to me is having information that guides me and knowing how to proceed with my child," emphasizing the importance of practical guidance.

Personal Reflection and Self-Regulation

Personal reflection and self-regulation emerged as pillars in creating a more harmonious family environment. One participant confessed, "We realized that not only our child faces challenges, but we as parents also have a role in this," revealing a collective recognition of the need for personal change. Another father indicated, "This program led us, as a family, to better understand who our children are and what specific tools we can apply," underscoring how self-reflection led to practical actions and positive changes within the family unit.

Practical Application of Learned Strategies

The practical application of strategies in daily situations was crucial for parents. One participant affirmed, "In the end, all the strategies helped control the complicated situations we faced," showing how theoretical training translated into practical actions. Another mother noted, "Each concept covered in the modules had a real impact when applied at home," validating the program's effectiveness in real-world application.

Emotional Experiences and Group Sharing

The focus group highlighted the importance of emotional support and solidarity among parents. One father commented, "We discovered that we all had similar challenges, and that brought us together," while another added, "Sharing in the group provided us with new perspectives and made us feel that we were not alone in this."

Adapting Strategies to Individual Needs

Finally, the ability to adapt strategies to individual situations emerged as a critical skill. One father expressed, "It is essential to apply the learned strategies flexibly, considering each child's specific time and context." Another participant agreed, "There is no one-size-fits-all approach; each strategy requires adjustments to align with each family's and child's needs," reaffirming the need for personalization in managing ADHD.

Discussion

The “Living with ADHD as a Family” behavioral and neurocognitive program yielded encouraging but mixed outcomes in managing ADHD symptoms and parental stress. ECBI results suggested meaningful reductions in both the intensity and perceived problematic nature of children’s disruptive behaviors, with several parents reporting substantial improvements on the Intensity and Problem Scales. However, two parents showed deterioration on the Intensity Scale, underscoring the need to better understand individual variability in treatment response. Overall, these findings are consistent with prior research showing that asynchronous behavioral parent training can reduce problem behavior, while also producing heterogeneous outcomes across families (Marquet-Doleac et al., 2024; Thongseiratch et al., 2020).

Qualitative data from the PCSQ, rubric, and focus group complemented these results. Parents generally described their children’s ADHD-related difficulties as “better” or “slightly better” and reported feeling “satisfied” or “very satisfied” with progress, even when ECBI scores did not always reflect improvement. This discrepancy suggests that parents’ subjective perceptions may diverge from standardized measures of problem behavior (Thongseiratch et al., 2020). It is also consistent with previous research showing that problem behaviors may persist despite intervention due to challenges in implementing behavioral procedures, time demands, treatment fidelity, and broader family stressors (Gerdes et al., 2015; Marquet-Doleac et al., 2024).

The PSI-SF results indicated mixed outcomes in parental stress. Several participants showed significant reductions in Parental Distress (PD) and Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction (P-CDI), as well as improvements on the Difficult Child subscale and Total Stress scores, suggesting that the program helped alleviate stress and strengthen parent–child relationships. However, others reported increased stress across these domains. Prior research suggests that parental stress often stems not only from children’s challenging behaviors but also from unmet support needs and social stigma (Craig et al., 2020). While the program directly targeted behavioral difficulties, these broader contextual factors lay beyond the scope of this pilot, which may help explain the heightened stress reported by some parents post-intervention. Within this pattern, differences between mothers and fathers were evident, the largest PSI-SF improvements were reported by the three participating fathers (P2, P4, P6), whereas most mothers showed increased stress, with only P2, P6, and P7 displaying small, non-significant improvements in PD and P-CDI. This pattern aligned with previous work documenting modest changes in maternal stress and comparatively greater gains among fathers (Craig et al., 2020; Marquet-Doleac et al., 2024).

At the same time, PSI-SF scores only partially captured the program’s impact. Qualitative data from focus groups, consumer satisfaction questionnaires, and rubric evaluations provided a richer account of change. Parents described the training as helpful for managing and reflecting on stressful situations and reported feeling better equipped to handle difficult behaviors and attend to their children’s needs, often citing strategies such as staying calm and using breathing exercises. Many noted that the program helped them recognize and begin to address their own stress, even when overall levels remained high, suggesting that gains in coping and insight may precede measurable reductions. Taken together, these qualitative insights indicated that, despite some quantitative setbacks, the program substantially helped many parents manage stress and improve interactions with their children. They also supported the view that standard measures like the PSI-SF may not fully capture the complexity of parenting stress, underlining the need for refined cut-off scores and additional indicators to better identify families requiring support (Leitch et al., 2019). Unmet support needs and social stigma—factors not directly targeted—likely contributed to persistent distress, whereas sharing experiences with other parents reduced feelings of isolation and highlighted the value of peer support and priorities for refinement in future iterations.

The SNAP-IV results similarly revealed a mixed impact on ADHD core symptoms. Seven parents, including two fathers (P2, P6), reported meaningful reductions in inattention, while three mothers noted deterioration. For hyperactivity/impulsivity, two fathers (P2, P6) and four mothers showed significant improvement, but one father (P4) and three mothers reported worsening symptoms. Overall, total ADHD scores decreased for two fathers and five mothers, although one father (P4) and three mothers showed deterioration, suggesting that the program’s effects were promising but not uniform. These findings were consistent with previous studies on parent training for children with ADHD (Marquet-Doleac et al., 2024). Several factors may have influenced this pattern, after training, parents may become more aware of ADHD symptoms and therefore rate behaviors as more problematic; mothers and fathers may perceive change differently; and core symptom change often requires more time to emerge than the five-week, no-follow-up design allowed.

Despite these limitations, focus group responses and satisfaction questionnaires provided compelling evidence of improved management of core ADHD symptoms and greater parental confidence, supporting the program’s feasibility and acceptability. Parents’ reflections and concrete examples of strategy use indicated that they applied what they learned and perceived meaningful benefits. In line with prior research suggesting that parenting stress decreases when parents observe improvements in children’s behavior and ADHD symptoms (Craig et al., 2020; Doffer et al., 2023), reductions in parent–child dysfunctional interaction in this study were frequently associated with better ECBI problem scores (in three fathers and two mothers, P5 and P7) and improved SNAP-IV total ADHD scores (in two fathers, P2 and P6, and five mothers). These findings suggest that modifying parent–child interactions may be a key mechanism underlying perceived improvements in both children’s problem behaviors and ADHD core symptoms.

Qualitative insights further clarified how families experienced and implemented change. A central theme was the integration of strategies across home and school settings. Consistent with prior work on family–school collaboration (Garbacz et al., 2022; Pfiffner et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2022), parents reported sharing strategies with teachers and seeking greater consistency, which supported continuity and shared responsibility. Psychoeducation emerged as another cornerstone, parents emphasized that understanding ADHD and its mechanisms increased their confidence and sense of efficacy, echoing research on experiential and co-constructed learning (Dahl et al., 2020). The program also appeared to enhance self-reflection and emotional regulation, domains known to influence effective parenting but often under-addressed in traditional interventions (Mazzeschi et al., 2019).

Practical application of strategies was described as one of the most impactful elements. Families reported adapting techniques (e.g., reinforcement, routines, clear instructions) to their own routines and values, aligning with behavioral parent training models that emphasize consistent yet flexible implementation (Dekkers et al., 2022; van der Oord & Tripp, 2020). Group-based emotional support further reduced isolation and fostered a sense of shared identity among parents (Frigerio & Montali, 2016; Klein et al., 2019). Adaptability thus emerged as a defining feature of success, underscoring the importance of tailoring interventions to diverse family contexts and suggesting concrete directions for strengthening future iterations of the program.

Limitations and Future Research

This pilot study provided valuable preliminary evidence but has several limitations. The small, convenience sample limits generalizability, reliance on self-report introduces potential bias, and the absence of a control group prevents firm attribution of changes to the intervention. Future studies should use larger, more diverse samples and include control conditions to strengthen internal and external validity.

Measurement issues also warrant attention. Although we used a SNAP-IV validated in Argentina and a Spanish (Spain) version of the ECBI, cultural and linguistic differences may have affected responses. Locally adapted versions for the Colombian population are needed to improve reliability and cultural sensitivity. In addition, the lack of follow-up means that longer-term changes in ADHD core symptoms and problem behaviors could not be assessed; subsequent trials should incorporate multiple follow-up assessments.

As a pilot, the study also faced procedural challenges. During the focus group, participants identified confusion with one instruction that may have led to unexpected responses, and some parents reported technological barriers accessing the modules. While the content was translated into Spanish, it was not fully culturally adapted; despite expert review, certain materials may have been difficult to grasp. Future research should prioritize systematic cultural adaptation, clearer instructions, and user-friendly delivery platforms. Finally, extending this training protocol to schoolteachers, who play a central role in supporting children with ADHD, represents a crucial next step for broader implementation and impact.

Conclusions

The "Living with ADHD as a Family"

behavioral and neurocognitive program has shown promising results, indicating

significant improvements in managing children's ADHD core symptoms and reducing

parental stress. Most parents reported high satisfaction with their child's

progress, and qualitative feedback highlighted effective stress management

techniques. However, mixed outcomes in parental stress and ADHD symptom

assessments suggest the need for refinement to address individual differences

and external factors such as unmet support needs and social stigma. Given these

findings, the program appears both acceptable and feasible for large-scale

implementation. Its positive impact on many families, coupled with high

parental satisfaction, supports its broader application. Future enhancements

should focus on ensuring consistent outcomes across diverse participants and

incorporating comprehensive support measures to further improve the program's

efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to our research assistants, Sofía Téllez, María José Camargo, María Paula Ruano, Mariluna Gallo, Juliana Navarro, and Fabián Ramírez, for their invaluable support at various stages of this study. We are also deeply thankful to the parents who participated; their commitment made this project possible. We hope that our efforts contribute to improving the lives of their children.

This research was funded by the Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación que Contribuyen a la Misión de las Obras de la Compañía de Jesús, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, 2023 (VRI16-2022). The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study. Artificial intelligence tools were used solely to assist with refining the grammar and style of the manuscript. All scientific content, including data analysis, theoretical development, conceptual discussion, and interpretation of findings, was entirely created and conducted by the authors. No AI-generated content was used in developing the manuscript’s core material. The authors assume full responsibility for the accuracy and integrity of the content presented.

References

Abidin, R.R. (1995). Parenting Stress Index (PSI) manual (3rd ed.). Pediatric Psychology Press.

Ayano, G., Demelash, S., Gizachew, Y., Tsegay, L., & Alati, R. (2023). The global prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: An umbrella review of meta-analyses. Journal of Affective Disorders, 339, 860–866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.07.071

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. SAGE Publication.

Bussing, R., Fernandez, M., Harwood, M., Hou, W., Garvan, C. W., Eyberg, S. M., & Swanson, J. M. (2008). Parent and teacher SNAP-IV ratings of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms: Psychometric properties and normative ratings from a school district sample. Assessment, 15(3), 317-328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313888

Chacko, A., Bedard, A. C., Marks, D., Gopalan, G., Feirsen, N., Uderman, J., ... & Ramon, M. (2018). Sequenced neurocognitive and behavioral parent training for the treatment of ADHD in school-age children. Child Neuropsychology, 24(4), 427-450. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2017.1282450

Chronis-Tuscano, A., O'Brien, K., & Danko, C. M. (2020). Supporting caregivers of children with ADHD: An integrated parenting program, Therapist Guide. Oxford University Press.

Craig, F., Savino, R., Fanizza, I., Lucarelli, E., Russo, L., & Trabacca, A. (2020). A systematic review of coping strategies in parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 98, 103571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2020.103571

Dahl, V., Ramakrishnan, A., Spears, A. P., Jorge, A., Lu, J., Bigio, N. A., & Chacko, A. (2020). Psychoeducation interventions for parents and teachers of children and adolescents with ADHD: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32(2), 257–292. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-019-09691-3

De la Barra, F., Vicente, B., Saldivia, S. & Melipillan, R. (2015). Epidemiología del TDAH en niños y adolescentes chilenos. Revista Chilena de Psiquiatría y Neurología de la Infancia y Adolescencia, 26(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-012-0090-6

Dekkers, T. J., Hornstra, R., van der Oord, S., Luman, M., Hoekstra, P. J., Groenman, A. P., & van den Hoofdakker, B. J. (2022). Meta-analysis: Which components of parent training work for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(4), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.015

Doffer, D. P., Dekkers, T. J., Hornstra, R., Van der Oord, S., Luman, M., Leijten, P., ... & Groenman, A. P. (2023). Sustained improvements by behavioural parent training for children with attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A meta‐analytic review of longer‐term child and parental outcomes. JCPP Advances, 3(3), e12196. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12196

Drechsler, R., Brem, S., Brandeis, D., Grünblatt, E., Berger, G., & Walitza, S. (2020). ADHD: Current concepts and treatments in children and adolescents. Neuropediatrics, 51(5), 315–335. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701658

Dwyer, P. (2022). The neurodiversity approach(es): What are they and what do they mean for researchers? Human Development, 66(2), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1159/000523723

Fernández de Pinedo, R. (1998). Spanish version of ECBI (Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory): measurement of validity. AtenciónPrimaria, 21(2), 65-74.

Fleitlich-Bilyk, B., & Goodman, R. (2004). Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 727-734. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000120021.14101.ca

Frigerio, A., & Montali, L. (2016). An ethnographic-discursive approach to parental self-help groups: The case of ADHD. Qualitative Health Research, 26(7), 935–950. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315586553

Gallardo-Saavedra, G., Martínez-Wbaldo, M. & Padrón-García, A. (2019) Prevalencia de TDAH en escolares mexicanos a través de un cribado con las escalas de Conners 3. Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría, 47(2), 45–53. https://actaspsiquiatria.es/index.php/actas/article/download/207/273/282

Garbacz, A., Godfrey, E., Rowe, D. A., & Kittelman, A. (2022). Increasing parent collaboration in the implementation of effective practices. Teaching Exceptional Children, 54(5), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/00400599221096974

Galvin, E., Gavin, B., Kilbride, K., Desselle, S., McNicholas, F., Cullinan, S., & Hayden, J. (2024). The use of telehealth in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A survey of parents and caregivers. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 33(12), 4247-4257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-024-02466-y

Gerdes, A. C., Kapke, T. L., Grace, M., & Castro, A. (2021). Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes of a culturally adapted evidence-based treatment for Latino youth with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(3), 432–447. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718821729

Gerdes, A. C., Kapke, T. L., Lawton, K. E., Grace, M., & Dieguez Hurtado, G. (2015). Culturally adapting parent training for Latino youth with ADHD: Development and pilot. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 3(2), 71. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000032

Grañana, N., Richaudeau, A., Gorriti, C. R., O'Flaherty, M., Scotti, M. E., Sixto, L., ... & Fejerman, N. (2011). Evaluación de déficit de atención con hiperactividad: La escala SNAP IV adaptada a la Argentina. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 29, 344-349. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1020-49892011000400011

Hornstra, R., Groenman, A. P., Van der Oord, S., Luman, M., Dekkers, T. J., van der Veen‐Mulders, L., ... & van den Hoofdakker, B. J. (2023). Which components of behavioral parent and teacher training work for children with ADHD? A metaregression analysis on child behavioral outcomes. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 28(2), 258-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12560

Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.12

Klein, O., Walker, C., Aumann, K., Anjos, K., & Terry, J. (2019). Peer support groups for parent-carers of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The importance of solidarity as care. Disability & Society, 34(9–10), 1445–1461. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1584090

Kofler, M. J., Sarver, D. E., Austin, K. E., Schaefer, H. S., Holland, E., Aduen, P. A., ... & Lonigan, C. J. (2018). Can working memory training work for ADHD? Development of central executive training and comparison with behavioral parent training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86, 964. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000322

Lambek, R., Sonuga-Barke, E. J., Lange, A. M., Carroll, D. J., Daley, D., & Thomsen, P. H. (2023). Parent training for ADHD: No generalization of effects from clinical to neuropsychological outcomes in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Attention Disorders, 27(1), 98-107. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547221086490

Landínez-Martínez, M., Sánchez-Avendaño, A., Rodríguez-Cano, A. M., & Gantiva, C. (2025). Academic and neuropsychological performance in Colombian children with ADHD. Preprints, 2025040114. https://doi.org/10.20944/preprints202504.0114.v1

Leitch, S., Sciberras, E., Post, B., Gerner, B., Rinehart, N., Nicholson, J. M., & Evans, S. (2019). Experience of stress in parents of children with ADHD: A qualitative study. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 14(1), 1690091. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2019.1690091

Lu, S. V., Leung, B. M. Y., Bruton, A. M., Millington, E., Alexander, E., Camden, K., Hatsu, I., Johnstone, J. M., & Arnold, L. E. (2022). Parents’ priorities and preferences for treatment of children with ADHD: Qualitative inquiry in the MADDY study. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(5), 852–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12995

Marquet-Doleac, J., Biotteau, M., & Chaix, Y. (2024). Behavioral parent training for school-aged children with ADHD: A systematic review of randomized control trials. Journal of Attention Disorders, 28(3), 377-393. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547211049877

Mazzeschi, C., Buratta, L., Germani, A., Cavallina, C., Ghignoni, R., Margheriti, M., & Pazzagli, C. (2019). Parental reflective functioning in mothers and fathers of children with ADHD: Issues regarding assessment and implications for intervention. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00263

McAleavey, A. A. (2024). When (not) to rely on the reliable change index: A critical appraisal and alternatives to consider in clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 31(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000203

McAloon, J., & de la Poer Beresford, K. (2023). Online behavioral parenting interventions for disruptive behavioral disorders: A PRISMA based systematic review of clinical trials. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 54(2), 379–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01253-z

McMahon, R. J., & Forehand, R. L. (2003). Helping the noncompliant child: Family-based treatment for oppositional behavior. Guilford Press.

Michanie, C., Kunst, G., Margulies, D. S., & Yakhkind, A. (2007). Symptom prevalence of ADHD and ODD in a pediatric population in Argentina. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(3), 363-367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707299

Njardvik, U., Wergeland, G. J., Riise, E. N., Hannesdottir, D. K., & Öst, L. G. (2025). Psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents with ADHD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 102571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2025.102571

Pfiffner, L. J., Villodas, M., Kaiser, N., Rooney, M., & McBurnett, K. (2013). Educational outcomes of a collaborative school–home behavioral intervention for ADHD. School Psychology Quarterly, 28(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000016

Paiva, G. C. D. C., de Paula, J. J., Costa, D. D. S., Alvim-Soares, A., Santos, D. A. F. E., Jales, J. S., ... & Miranda, D. M. D. (2024). Parent training for disruptive behavior symptoms in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1293244. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1293244

Pineda, A., Lopera, F., Henao, C., Palacio, D., Castellanos, X. & Fundema, I. (2001). Confirmación de la alta prevalencia del trastorno por déficit de atención en una comunidad colombiana. Revista de Neurologia, 32, 217–222. http://www.neurologia.com/pdf/Web/3203/k030217.pdf

Rich, B. A., & Eyberg, S. M. (2001). Accuracy of assessment: The discriminative and predictive power of the Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory. Ambulatory Child Health, 7, 249–257. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-0658.2001.00137.x

Rivas, G. R., Arruabarrena, I., & de Paúl, J. (2021). Parenting stress index-short form: Psychometric properties of the Spanish version in mothers of children aged 0 to 8 years. Psychosocial Intervention, 30(1), 27-34. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2021a1

Salari, N., Ghasemi, H., Abdoli, N., Rahmani, A., Shiri, M. H., Hashemian, A. H., ... & Mohammadi, M. (2023). The global prevalence of ADHD in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 49(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-023-01456-1

Sibley, M. H., Bruton, A. M., Zhao, X., Johnstone, J. M., Mitchell, J., Hatsu, I., ... & Torres, G. (2023). Non-pharmacological interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 7(6), 415-428. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00381-9

Smith, T. E., Holmes, S. R., Romero, M. E., & Sheridan, S. M. (2022). Evaluating the effects of family–school engagement interventions on parent–teacher relationships: A meta-analysis. School Mental Health, 14(2), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-022-09510-9

Tai, R. H., Bentley, L. R., Xia, X., Sitt, J. M., Fankhauser, S. C., Chicas-Mosier, A. M., & Monteith, B. G. (2024). An examination of the use of large language models to aid analysis of textual data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 23, 16094069241231168. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069241231168

Thongseiratch, T., Leijten, P., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2020). Online parent programs for children’s behavioral problems: A meta-analytic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(11), 1555-1568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-019-01329-4

Unda Villafuerte, F. S., Durán Agudelo, N. E., Juca Pañega, M. E., Aguirre-Vargas, I. C., & Vásconez Campos, M. E. (2023). Elementos para el debate crítico sobre inclusión, decolonialidad y educación para la salud. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 7(4), 3079-3094. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v7i4.7158

van der Oord, S., & Tripp, G. (2020). How to improve behavioral parent and teacher training for children with ADHD: Integrating empirical research on learning and motivation into treatment. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 23(4), 577–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-020-00327-z

Van Manen, M. (2023). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Routledge.

Vélez‐Calvo, X., Tárraga‐Mínguez, R., Roa‐López, H. M., & Peñaherrera‐Vélez, M. J. (2024). Prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptomatology in Ecuadorian schoolchildren (aged 6–11). Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 24(2), 429-438. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12642

Wachinger, J., Bärnighausen, K., Schäfer, L. N., Scott, K., & McMahon, S. A. (2024). Prompts, pearls, imperfections: Comparing ChatGPT and a human researcher in qualitative data analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 10497323241244669. https://doi.org/10.1177/10497323241244669

Wang, C., Hou, L., Zhou, H., Wang, Q., Yan, H., Lang, Y., ... & Liu, J. (2025). The evolving global burden of ADHD: A comprehensive analysis and future projections (1990-2046). Journal of Affective Disorders, 391, 120037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2025.120037

Whittingham, K., & Coyne, L. (2019). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The clinician's guide for supporting parents. Academic Press.

Wilens, T. E., Stone, M., Lanni, S., Berger, A., Wilson, R. L., Lydston, M., & Surman, C. B. (2024). Treating executive function in youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A review of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. Journal of Attention Disorders, 28(5), 751-790. https://doi.org/10.1177/10870547231218925

Zelazo, P. D. (2020). Executive function and psychopathology: A neurodevelopmental perspective. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 431-454. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072319-024242

Notes

*

Research

article.

Author notes

a Correspondence author.

Email: yors.garcia01@javeriana.edu.co

Additional information

How to cite: García, Y., Martínez, L. F., &

Martínez-Martínez, A. (2026). Acceptability and feasibility of an online

training program for parents of children with ADHD. Universitas

Psychologica, 25, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy25.afot