Introduction

Large-scale monitoring programs frequently fail to consider how they alter the presumption of innocence. With the prevalence of internet surveillance in today’s environment, fears about individual rights and data privacy have greatly increased. Despite the fact that tracking is generally thought to be efficient in preventing crime, it also involves the potential of false allegations, which can especially harm disadvantaged populations. While researchers such as (Lyon 2022)

1

have expressed attention regarding the regression of personal license brought about by continuous surveillance, Murakami Wood and Webster (2019)

2

confirm that while surveillance may be useful in clearing innocent people, it also grows the likelihood of false accusations when privacy principle are infringed. The cause of this research is to scan the ethical and legal ramifications of mass surveillance technologies and how they challenge the presumption of innocence. Three essential questions are studied: What is the action of control on the assumption of innocence? What moral and legal questions are raised by its implementation? What legislative frameworks are required to strike an equilibrium between public protection and private privacy? The essay provides helpful advice to ensure that surveillance technologies be applied ethically, preserving human freedoms liberties and the concept of innocence while meeting the request of public security.

Real-World Impacts of Mass Surveillance on the Presumption of Innocence

UK

The base of presumption of innocence, which is a legal standing legal foundation, has been affected by the extensive setup of CCTV cameras in operations across the UK, where the government utilizes them as a crime dominance strategy and also for investigation goal. According to Bennett & Raab (2018),

3

notwithstanding the arrangement’s efficacy success in surveillance of public space, it is often associated with negative outcomes like reduction of license of individuals and increasing umbrage among the disadvantaged who may feel they have been targeted unfairly.

Despite legal measures like the Data Protection Act and the Investigatory Powers Act, questions remain about the effectiveness of these regulations in truly protecting privacy rights. The European Court of Human Rights has emphasized that surveillance must be justified in a democratic society; however, unauthorized access to CCTV footage for non-criminal purposes continues to highlight issues with protecting individual rights.

4

Although the UK’s extensive CCTV network has helped reduce crime, it has also contributed to wrongful accusations. A 2020 report by the London Metropolitan Police found that 15 % of cases involving CCTV footage resulted in misidentification of suspects, showing the risks of relying too much on surveillance.

5

After the implementation of the Investigatory Powers Act, a 2022 report by the Information Commissioner’s Office noted a 20 % decrease in incidents of unauthorized data access, suggesting some improvements in regulating surveillance practices.

6

The United States

The USA Patriot Act, which gave the federal law enforcement and security agencies extensive powers without the usual court mandate, was the main system used to greatly spread the United States’ surveillance rule following the 9/11 attacks This made it possible to take a lot of data often without the agreement of the people from a variety of private entities, such as credit unions and ISPs. Because it permitted the vast gathering of phone input which uncovered intricate style of people’s actions, Section 215 was especially contentious. Even Americans were affected by the 2007 introduction of the PRISM program, which made it possible to collect data from large internet groups. The range of the program was made public by Edward Snowden’s 2013 detection. Highlighting issues about religious certain by drawing alertness to the supervision hole and its disproportionate wares on some population’s communities. The American Freedom Act was come in 2015 in response to public anger to reduce mass data collection; nevertheless, several holes still occur, notably as Section 702’s ongoing surveillance of foreign connection. Mass surveillance in the United States at this time focus the continuous stress between national protection and individual liberties, posing questions with data privacy and the deterioration drop of the presumption of innocent. While the government maintains that these measures are necessary to deter terror threats, they continue to generate issues about data protection, the foundational legal concept, and the influence on marginalized communities. The US experience highlights the challenge of conducting monitoring activities in a way that safeguards personal rights while without intruding on their basic freedoms.

7

The PRISM program’s extensive data gathering has raised severe issues about personal data protection and unfounded charges. According to the EFF (2021), approximately 10 % of PRISM data-related legal cases resulted in incorrect charges, unfairly affecting marginalized groups. The USA Freedom Act, aimed to prevent overcollection of information, has decreased unlawful incarcerations by 30 %, according to a GAO analysis, indicating modest improvement in civil rights safeguarding.

8

China

The Social Credit System China’s SCS is a wide-ranging form of monitoring that goes far beyond only monitoring unlawful activities. This approach assigns individuals a reputation rating based on a variety of factors such as their online behavior, bill payment punctuality, and adherence to societal norms. These scores ratings can influence access to essential resources like financial assistance, job opportunities, movement, and learning.

9

By tying behaviors to benefits and sanctions, the system shapes how people respond, generating a constant sense of being observed and evaluated. This form of surveillance not only tracks citizens but also affects their daily behaviors, reducing their liberty and potential.

10

While the system aims to promote reliability and public accountability it has raised severe problems about confidentiality and civil liberties. People may be sanctioned for small actions that are not criminal infractions, such as social minor mistakes or unsettled debts.

11

This weakens the legal assumption of non-guilt since individuals are rated based on their behavior and data obtained without a fair legal review.

12

Even in situations when rules are didn’t broken, China’s Social Credit System frequently infers guilt fault based on surveillance information.

13

More than 15 million persons have been punished for data fault or small violations as a result, which has had serious effects.

14

There are still trouble even with the new data protection laws of 2020. According to Amnesty International (2022),

15

40 % of situations lacked clarity, which led to persistently harsh sanctions and raised issues with individual freedoms and data privacy security. The style has been widely condemned for its excessive reliance on surveillance data according to a situation documented by Human Rights Watch (2022).

16

According to a 2021 research, 65 % of individuals are scared about data fault in the system.

In 2021, China reacted by passing the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which gave the public more hold over data acquisition. Major problems still occur, though, particularly with the Social Credit System. Extensive data gathering is still allowed under national security exceptions, undermining privacy defines and putting persons to unjust penalties.

17

Russia

Russia prefers national defence over personal protection, which leads to widespread governmental control. Laws such as the Yarovaya Law and the SORM system require extensive data storage and provide the government immediate entry to telecommunications information.

18

Moscow uses face recognition technology to monitor people in real time, often focusing on demonstrators and political protestors.

19

The presumption of innocence is weakened by this widespread controlling, which also makes people feel constantly observed and causes them to self-censor their words and actions. Significant ethical and legal issues about abuse and unjust arrests are heighted by Russia’s emphasis on safety above privacy, which stands in stark contrast to the European Union’s focus on data privacy.

20

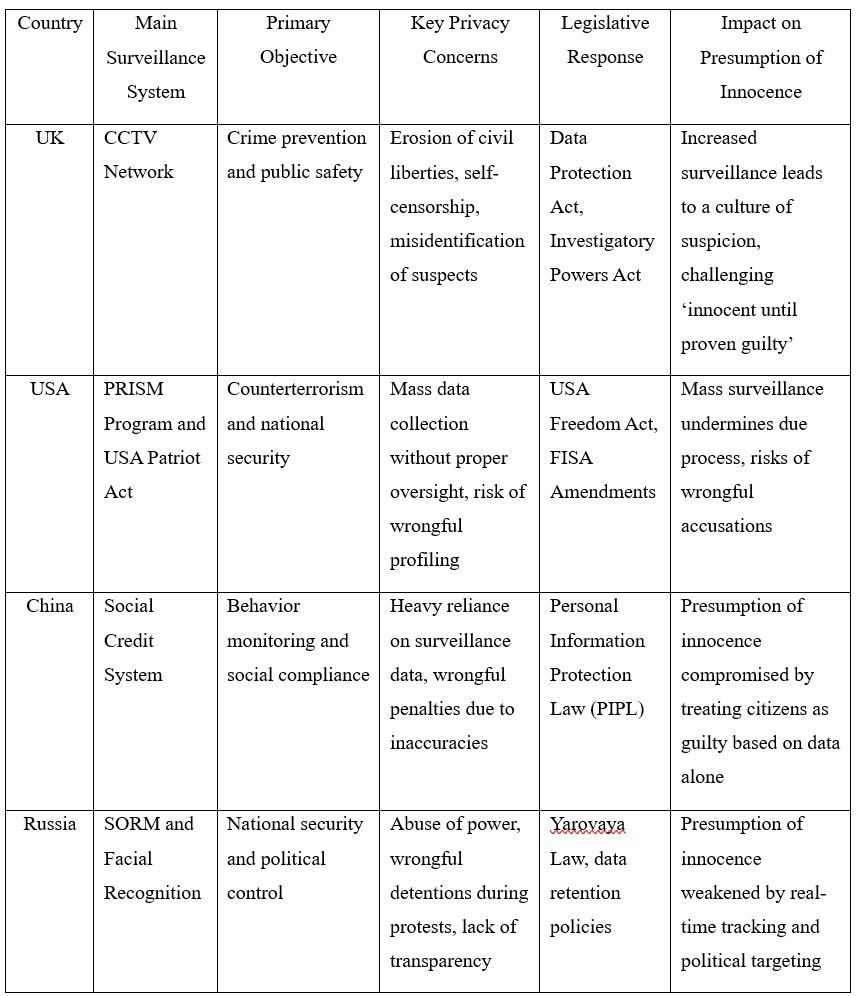

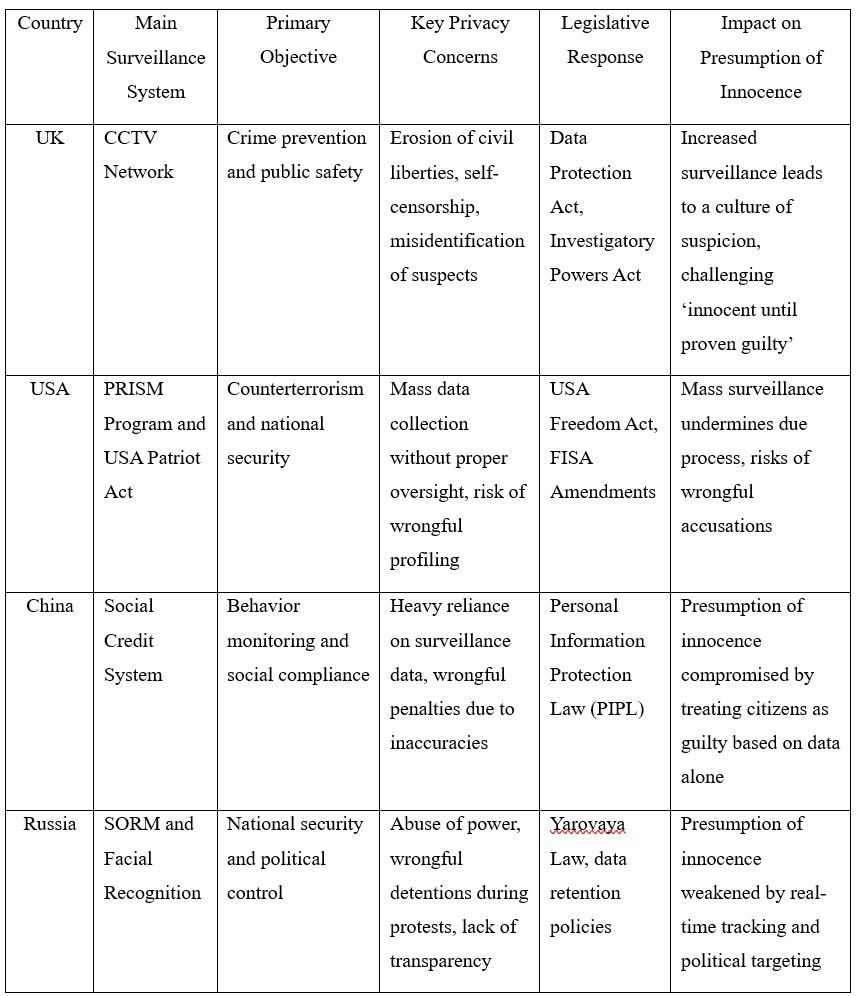

The situation serves as an alert about the risks of giving governmental jurisdiction priority over personal freedoms and privacy rights keeping (Table 1).

Table 1.

Methods

to large-scale monitoring in different countries

Source: Own elaboration.

Table 1 outlines the various methods to large-scale monitoring in different countries, each defined by government regulations. Regardless of the differences in monitoring methods—ranging from the PRISM program in the United States to China’s public trust scheme—a common theme appears: the broad use of surveillance records frequently leads to substantial confidentiality problems and tests the premise of legal presumption of innocence. Legal actions, such as the USA Freedom Act and China’s Personal Information Protection Law, aim to tackle these challenges, but execution is irregular, especially in repressive regimes. This cross-country study emphasizes the vital need for robust legal protections that combine safety issues with the protection of personal liberties.

Legal Reforms and Safeguards As monitoring systems develop, it becomes clear that existing regulatory structures are inadequate to protect personal freedoms, particularly the legal assumption of non-guilt. closed-circuit television, facial recognition, and various information-gathering tools are frequently used without proper oversight, resulting in a dangerous imbalance between community protection and the protection of personal freedom.

However, people are seen as possible suspects in the absence of clear-cut evidence, which can result in unfounded accusations.

21

To ensure that all of those surveillance technologies are used in a way that preserves people’s privacy and autonomy, we need to amend the laws governing these issues. The creation of unbiased committees to supervise those systems would be the biggest modification. These organizations should be able to perform routine scanning and evaluate the results before putting any new monitoring equipment into place. By using activity monitoring systems, this would protect human rights and stop privacy violations.

22

Legal

Reforms and Safeguards

The idea of the presumption of innocence is one example of how evolving monitoring technology highlights a weakness in the legal frameworks safeguarding individual liberty. Frequently, data-collection tools like facial recognition and CCTV systems are used without oversight and hence lead to a dangerous imbalance between the defense of personal freedom and the community’s security. This lack of rules produces a system in which people are considered as potential offenders in the absence of strong corroboration, which can lead to mistaken claims.

23

Legal frameworks must be updated to ensure that surveillance systems respect people’s freedoms to personal space and individual control and are ethically principled. Independent regulatory authorities must be created to conduct evaluations and effect dissection before new technology is implemented in order to stop breaches of civil liberties.

24

Data acquisition should be confined to relevant data regarding illegal actions in order to avoid over-tracking the public.

25

People must also be able to access and contest the information recorded about them in order to guarantee equitable processing.

26

Clarity and clear policies on data utilization and keeping are crucial to preventing control from being abused for political aims.

27

Public security may be enhanced by controlling but basic liberties must not be compromised. The presumption of innocent is a fundamental principle of justice, and legal systems should strike an equilibrium between security and personal space,

28

developing international standards that respect human freedoms and secure moral monitoring strategies requires collaboration between countries.

29

In the US, China, Russia, and the UK journalists influence views on monitoring. The media in the UK highlights liberties vs s protection. Privacy issues are highlighted by PRISM coverage in the USA. While critics draw attention to rights concerns, official media in China supports the social credit system. Worries about privacy are highlighted by the media’s emphasis on face identification in Russia. In general, the media affects shifts in public opinion and laws.

Methodology

This research examines the impacts of extensive monitoring on the assumption of non-guilt using a descriptive approach.

30

The study is to examine the effects of monitoring systems on individual freedoms and privacy, including identity surveillance, CCTV, and internet tracking.

Case Study Selection

Research cases were picked to reflect countries with different political systems and well-publicized initiatives for surveillance.

31

It was chosen as a state case study due to its extensive video surveillance, demonstrating the nation’s widespread deployment of CCTV in public spaces. Because of its noteworthy data collection practices, such as the PRISM program, which raise issues regarding internet privacy. The United States was selected, the decision was also influenced by the fact that public scoring in China is government-controlled for public oversight. Finally, Russia was chosen to illustrate the widespread use of modern face-tracking technology in public areas. In addition to reflecting a variety of legal and political contexts, these case studies were selected to offer a comprehensive analysis of global surveillance technologies and their impact on individual liberties.

Data Collection

This study used indirect sources, including government documents, credible media, and carefully selected scholarly publications.

32

Our attention was drawn to publications that were released within the last ten years, whose content was selected based on its relevance to current affairs. Because there is a lack of primary data and tracking monitoring techniques are limited, especially in repressive nations, existing resources were used.

33

This method limits the chance of secondary data bias by utilizing only trustworthy and validated data.

Analytical Approach

The data was analyzed through a thematic review: it primarily focused on recurring themes such as misleading claims, a decline in individual rights, and concerns regarding privacy issues.

34

This analytical method facilitated the systematic identification of crucial components across various study instances; thus, it led to a comprehensive understanding of how monitoring can undermine the legal presumption of non-guilt. Thematic analysis, however, effectively synthesized narrative details from diverse contexts, enabling an in-depth evaluation. Although this process is meticulous, it also reveals challenges that must be considered in future research.

Our research concentrated on peer-reviewed articles and high-quality publications over the years of 2015 to 2023 in order to ensure accurate and transparent source attribution. The categories were developed through a systematic classification method and assessed by another analyst to reduce subjectivity and increase the reliability of outcomes.

35

Reliability and Limitations

In order to strengthen the consistency of the analysis, inter-coder reliability was utilized: A second reviewer validated the coded data. Any inconsistencies were resolved through discussion.

36

However, despite these efforts, the study’s limitations stem from its reliance on secondary data, which may not fully reflect direct experiences. Furthermore, because the case studies come from countries with advanced monitoring systems, there exists a region-specific emphasis, which could restrict the applicability of the findings.

37

Rationale for Approach

The qualitative study design, in conjunction with pattern analysis, provided a reliable foundation for exploring the ethical and legal consequences of extensive monitoring.

38

This method uncovered the primary concerns regarding the legal presumption of non-guilt in an era characterized by pervasive observation. However, it allowed for a comprehensive review across various international contexts. Because secondary data was utilized in this study, a stringent selection procedure was implemented to ensure both the appropriateness and credibility of the sources. Although the approach was effective, it did not require field data collection, thereby simplifying the research process.

The focus was given to the integration of government documents, credible verified nonprofit findings, and reliable studies. Information was evaluated across various independent sources to strengthen the research and mitigate bias —particularly from data collected in regions with restricted access, such as the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation.

39

Future studies could potentially resolve this issue by utilizing primary sources, like focus group discussions; however, this research relied on indirect data because of the difficulties associated with obtaining surveillance data. Direct feedback from individuals who are subjected to monitored (or from security personnel) may provide critical viewpoints that deepen understanding of the real-world impacts on individual liberties and the legal principle of innocence.

Why the Presumption of Innocence is Valid?

Assumption of innocence stands as one of the core principles of criminal law; it ensures that the onus of proof lies with the prosecution and that a person is regarded as presumed innocent until guilt is proven. This concept, which prohibits convictions without hard proof, is crucial to guaranteeing that justice is carried out equitably. Also, it protects people from unjustified punishment and upholds their fundamental rights. International legal frameworks in the world uphold this idea. Even so, this fundamental idea is at danger, due to the growing use of surveillance technology. Even while it could improve security, people might be unjustly inspected. This makes us ask question about the presumption of innocence and the possible loss of privacy.

One of the cornerstones of the criminal justice system is the presumption of innocence and most importantly it confirms that the burden of evidence rests with the judicial system and that a person is assumed innocent unless and until proven guilty. This concept is necessary to ensure that justice is carried out fairly and to stop people from being unfairly convicted in the lack of solid proof. Further, it protects basic freedoms, guaranteeing that no one is subjected to unjust punishment. International legal norms that endorse this approach include the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). However, because various nations have different meanings, it may be more challenging to put these concepts into effect, and we should note that these documents establish a solid base, the real-word execution often faces hurdles.

But as surveillance technologies advance, this concept faces more and more difficulties. The usage of surveillance technologies, such as personal identification systems and closed-circuit television (CCTV), is increasing without sufficient legal oversight. At times, these systems classify people as suspects based on guesses or hunches rather than concrete facts.

The basic legal premise is seriously threatened by this shift from a verifiable evidence approach to assumption-based monitoring, which makes it possible to hold someone accountable even if they did nothing unlawful. Although, this dependence on speculation raises significant ethical issues. The outcomes of such activities might erode trust in legal systems, even when the goal may be to increase safety.

Discourses Relating to Reconnaissance

As reconnaissance innovations create, it is easy to understand that one of the foremost inconvenient impacts could be a misfortune of security. Researchers like Warren and Brandeis (1890) have long famous the association between the misfortune of individual opportunity and checking. However, since so numerous individuals are unconscious of its significance, this issue is as often as possible neglected. In spite of the benefits of innovation progression, there are genuine concerns almost individual space.

The growing implementation of surveillance has generated fears about the legal assumption of non-guilt, an essential legal protection that is currently at risk. Long-term extended monitoring using CCTV (closed-circuit television) and facial analysis technology can lead to unease, social labeling, and decreased loss of confidence. These findings are particularly troubling because they call into question the legal and moral basis for the foundational legal concept. Detractors state that in democracies, the presumption of innocence should be treated as both a fundamental value and a legal protection. Some legal specialists advise that applying this concept too broadly may lead to baseless fears about incorrect assertions. According to these academics the presumption should be applied more administratively particularly in court proceedings like trials. We firmly believe that the presumption of innocence should continue to be a pillar in preventing people from being wrongfully criminalized even though we acknowledge that surveillance systems may contribute to preserving public trust. The idea that people should be presumed innocent unless proven guilty through a fair and open legal process is one that we uphold in light of the expanding use of surveillance technologies. Maintaining the legal assumption of non-guilt is more essential than ever in preventing wrongful conviction, especially given the rapid developments in surveillance tools.

40,41

To defend individual legal protections and confidentiality, as well as to prevent innocent persons from being incorrectly flagged as suspects based purely on data or speculation, our legal systems must adapt with emerging tools.

42,

43

To achieve an equilibrium between the benefits of surveillance and the protection of core freedoms, clear legal protections and accountability frameworks are necessary.

44,,45

However, this necessitates careful consideration, because without such controls, the potential harms may outweigh the benefits. Although some may disagree, it is vital to establish these protections to maintain a just society.

Criminal Proceedings: The Right to Trust the Presumption of Innocence

The foundational legal concept is a core principle of penal law that holds an accused party innocent unless proven guilty. This principle places the responsibility to provide evidence on the legal accuser, guaranteeing that no one is unjustly considered at fault without evidence. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) both highlight the need for just legal processes in defending personal freedoms.

The growth of extensive surveillance tools, including CCTV, biometric identification, and mass data acquisition, poses substantial risks to the core legal safeguard. Surveillance systems that monitor individuals without their agreement or awareness are often used to spot suspects, even in the absence of concrete evidence. This transition, from a justice system focused on evidence to one driven by suspicion based on data, erodes the principle that individuals should only be treated as guilty once solid proof is presented. In the United Kingdom, for example, CCTV systems are used extensively, and although they can help solve crimes (resolve cases, aid investigations), they also create situations where individuals are treated as suspects based merely on their location in certain areas, without any real proof of criminal activity.

46

Similarly, in the United States, the PRISM program, which was revealed by Edward Snowden, demonstrates how mass data collection allows the government to monitor individuals without their knowledge, increasing the risk of wrongful profiling. This program is a classic example of how surveillance undermines the presumption of innocence by treating data as a sufficient sign of potential guilt. In order to build a scenario where people can be judged and sanctioned based on information rather than any actual illegal activity, this system monitors social behaviors, economic choices, and even viewpoints. Since it labels people as responsible for offenses without following the proper lawful protocols or receiving a just legal process, this directly conflicts with the core legal doctrine.

47

These cases demonstrate the increasing judicial challenges that develop when monitoring systems are permitted to function without appropriate control. Even though these technologies could enhance security, they also present serious risks to confidentiality and personal freedoms, especially when they are used to detect persons in advance based on unverified beliefs rather than factual verification. The fundamental concept that someone should only be judged responsible following a fair lawful proceedings and strong verification is weakened by this transition.

As surveillance continues to advance, it is essential that our legal systems adjust to ensure that individual rights are upheld. Clear legal protections and accountability mechanisms must be established to ensure that the use of surveillance does not violate on the presumption of innocence, and that individuals are not unjustly treated as suspects based on unreliable data or assumptions.

Illegal Prosecutions and Surveillance Overuse

When an individual is treated as though they have a tendency toward or are actively engaging in criminal behaviour when there are insufficient reasons for such an assumption, this is an example of unjustified criminalization. Unjustified criminalization is a form of overcriminalization. Unjust criminalization is at its worst when it leads to the conviction of innocent persons; this is precisely what the right to be presumed innocent is intended to prevent.

48

On the other hand, wrongful criminalization is at its mildest when it results in very modest intrusions of private space. When determining whether or not anything represents unjustifiable criminalization, we will consider not only how we respond to those who commit crimes, but also the characteristics that lend credence to labelling someone as a criminal. Both of these factors will play a part in our analysis. For the second half of your question, we can make the case that there are legitimate reasons when there is evidence that points to criminal behaviour in a way that is strong enough to warrant the suggested preventative or punitive action. In other words, we can argue that valid reasons exist when there is evidence that points to criminal behaviour.

These ideas will be discussed in the light of the question of whether or not particular kinds of surveillance lead to the unjustifiable categorization of certain individuals as criminals. In conclusion, in order to provide a comprehensive response to the problem, we need to investigate whether or not monitoring tactics invariably lead to the unlawful prosecution of persons, or whether or not, in principle, they might be deployed without doing so. Only then will we be able to determine whether or not certain monitoring strategies can be used without leading to the unwarranted prosecution of individuals.

49

Widespread or indiscriminate monitoring undermines the legitimacy of the government by falsely criminalizing individuals. It is difficult to present evidence against such pervasive criminalization practices because criminal behaviour is fundamentally abnormal and deviates from social norms. It would imply that the law is outdated to assume that everyone has the potential to commit crimes. Mass monitoring does not always violate the presumption of innocence because it does not single out innocent people for attention, despite the problems with these surveillance techniques.

50

The practice of classifying persons in accordance with the likelihood that they will engage in illegal activity constitutes a form of criminalization that can be observed in a variety of contexts. The backlash against police techniques of racial and ethnic profiling is a common example. The argument against these practices is that they criminalize not just the individuals who are targeted but also entire communities.

51

There are a couple strong counterarguments to this position. Regrettably, there are situations in which illegal activity takes place despite the fact that there is justification for the action that is being conducted. Customs officers may, for instance, conduct surveillance at the border in response to information received about a human trafficking ring maintained by individuals of a certain ethnic origin who transit between different locations. It is possible that the policy’s intended victims have this ethnic background; yet, the surveillance may lead to people of that origin being criminalized; this would be legitimate if the proof were sufficient. Due to the fact that we have been having this conversation, we have reached the realization that targeted surveillance does not necessarily result in the incorrect criminalization of behaviour. Surveillance, however, can and frequently does lead to wrongful criminalization.

It is pointless to try to discover, for the sake of this research, which sorts of monitoring are more likely to criminalize erroneously and, as a result, which types of surveillance can be considered as legally eroding the presumption of innocence because it is unnecessary to try to determine these things. This article attempts to get a knowledge of the impact that surveillance activities, in general, have on the presumption of innocence. Considering the high chance that these processes can and are used to safeguard individuals from being wrongfully charged of crimes and convicted of those charges, this article tries to gain an understanding of the impact that surveillance activities, in general. The preliminary research on this topic has been completed; monitoring practices have the potential to be utilized in ways that undermine the presumption of innocence by incorrectly identifying persons as criminals and do so. On the other hand, such applications are not required to take place. In addition to a more thorough analysis of the study, the prospect of gaining a better understanding of the research has also been investigated.

Value of Surveillance Evidence in Preventing Mis-Convictions

The surveillance techniques can and do already safeguard innocent individuals from being falsely prosecuted and convicted of crimes. There is no doubt that this is a contentious claim. As a consequence, of this, the individuals in question are spared the significant expenditures associated with going to trial or being convicted of crimes for which they were not liable. This can be accomplished in three different ways:

-

by

reducing the number of people who make false confessions;

-

by

making a greater quantity of exculpatory evidence available to the defines;

-

by

preventing law enforcement investigations from becoming myopic. The most recent

empirical research from the United States and the United Kingdom on the factors

that lead to erroneous convictions served as the foundation for the development

of these notions.

These hypotheses are plausible, and we should take them into consideration when framing and moving on with the conversation about how pervasive surveillance undermines the constitutional guarantee of the presumption of innocence. Social scientists are currently conducting research to investigate and validate these hypotheses about the factors that lead to wrongful accusations and convictions. Contrary to the ideas of certain legal theorists, there is not a large rise in the number of false convictions caused by the admission of hearsay or proof of a person’s bad character,

52

for example other factors, such as the partiality of the judge or the inability of the jury to properly evaluate the evidence, are more likely to be responsible for wrongful convictions. Misidentification of a suspect by a witness, fabrication of confessions, inefficiency on the part of both the defines and the prosecution, and (much less substantially) incorrect interpretation of forensic evidence are all factors that might lead to an incorrect conviction.

53

Instead of being caused by one or more of these components, they are the ones who are causing them.

When conducting a criminal investigation, it is not uncommon for detectives to experience tunnel vision in the early stages of the inquiry. It should thus not come as a surprise to anybody that the research also demonstrates that the causes for erroneous allegations and convictions lie in flaws that may be addressed most effectively by efforts taken in the relatively early phases of a case. These faults can be addressed most effectively by efforts taken in the relatively early stages of a case. According to the findings of various pieces of study, these mistakes become deeper rooted and more serious at each successive level of the legal system. As a consequence of this, relying on legal processes to fix them after the fact when they are already rather late in the game is not the most effective strategy for dealing with the issue. Putting corrective interventions into place far earlier, ideally even before suspects are formally charged with criminal offenses.

54

The evidence that may be obtained through surveillance has the potential to prevent or remedy the development of tunnel vision in law enforcement and, as a consequence, to combat what the findings of the research demonstrate to be the single most important factor in the occurrence of wrongful convictions. This can be done by preventing law enforcement from becoming overly focused on a single suspect or by focusing on multiple suspects at once. Taking steps to prevent the development of tunnel vision is one method that can be utilized in order to successfully complete this task. The easiest technique for achieving this objective, as well as one of the most effective ways, is to incorporate the gathering of evidence from surveillance into processes that are supposed to counteract tunnel vision. The appointment of ‘contrarians’ or devil’s advocates in countries such as Canada and the Netherlands are one example of a recent movement to adjust police investigative techniques in ways that challenge tunnel vision.

More examples include more recent initiatives.

55

Their role is to examine the judgments made during an investigation in an effort to head off the formation of prejudices or preconceived conceptions that could affect the outcome. These officers are acting on their own and are often called in from another agency.

No matter how far technological progress has come, the problem of tunnel vision will exist as long as a police department’s approach to criminal investigation places a higher value on the confirmation of a theory than it does on the uncovering of the truth. This is the case even if the technology in question is cutting edge. One may make the argument that it is mostly meaningless to speculate about how technologies might be employed in the future unless and until we change our attitude on the matter.

56

This argument is made in a way that is far too hasty, despite the fact that it contains a grain of truth. Tunnel vision is something that may be treated with particular technologies, and as a result, the likelihood of an innocent person being wrongfully convicted of a crime decreases when these technologies are utilized on a consistent basis. An illustration of a fingerprinting technique that is meant to be used in forensics. An attempt at a forensic drawing depicting the process of fingerprinting. In particular, DNA testing has been vital in helping to reverse the convictions of persons who were unfairly condemned. When it comes to preventing the wrongful conviction of innocent individuals and overcoming bias, DNA evidence, provided it is both easily available and accurate, can provide the required objectivity. In order to accomplish this goal, it is necessary to cut through the haze of ignorance and create a picture that is more accurate of the current circumstance. There is a possibility that the benefits associated with DNA evidence can also be applied to the evidence obtained through surveillance.

57

It is not inconceivable that, at some point in the future, the duty to collect CCTV evidence from crime scenes could be elevated to the position of a legal responsibility, and one could argue that it should be. In most cases, the police are not compelled to actively search for or gather evidence that would exonerate a suspect; but, in many jurisdictions, they are required to report the existence of any evidence that might exonerate a suspect. The law in the United Kingdom requires that investigations be conducted by the police following all ‘reasonable lines of inquiry,’ which is a higher standard than in the majority of other countries. As more people become aware of the various evidence sources, it is projected that there will be an increase in the number of legal actions taken against law enforcement. For instance, this can take place if those who were unfairly convicted argue that law enforcement officials had the ability and the duty to retrieve potentially exonerating CCTV footage but did not do so. In today’s culture, defendants almost never get an advantage as a result of this kind of legal argument. This is due to the fact that a lot of hinges on what is considered to be ‘reasonable,’ as well as the fact that it relies on a challenge from the defendant after the fact rather than factoring in protections from the very beginning of the process. It’s possible that digital collection will be a more cost-effective method of gathering evidence. The gathering of evidence using digital means might be a more cost-effective and efficient option.

58

Despite a wealth of research on the use of surveillance evidence in crime detection and prevention, no empirical study has yet to directly evaluate how it might clear suspects in court or exonerate them. Even though surveillance is frequently defended as a means of improving security, its contribution to maintaining the presumption of innocence is not well studied, indicating a disconnect between its security purpose and its capacity to shield people from false accusations.

59

Social Order’s Presumption of Innocence: Surveillance Impacts

There are issues with both of the potential choices that can be made. Even though it is feasible that more surveillance will result in fewer innocent individuals being criminalized overall, the fact that this is possible does not erase the reality that some people have been wrongfully convicted of crimes. At the very least, therefore, the aggregative method provides us with a footing on which to evaluate the influence of such measures on the presumption of innocent. An evaluation such as this could assist us in reaching conclusions regarding the general justifiability of such actions. On the other hand, it would appear that the second choice more accurately portrays the effect that monitoring has on the presumption of innocence because it separates the possibility of an incorrect suspicion from an improper conviction. However, a cursory examination reveals that it is less valuable than the first because it does not produce a distinct general judgment that could assist in informing more extensive policy concerns.

60

In spite of these things that need to be taken into account, there is at least one argument that can be made in support of selecting the second option, which is the non-aggregative one. The aggregative option can be thought of as a form of fundamental aggregative utilitarianism. Its purpose is to assess whether or not there has been interference with the presumption of innocence. Taking this approach would require comparing the potential advantage of preventing an inaccurate allegation and conviction against the potential risk of developing a wrongful suspicion as a result of monitoring activities. To restate, the aggregate option is best understood as a straightforward example of the utilitarian aggregate strategy. When the relative significance of avoiding erroneous suspicion and wrongful conviction is weighed against one another, utilitarian logic would place greater emphasis on the former. This is due to the fact that the interests that are at stake in erroneous conviction are more important to people’s well-being than those that are at stake in wrongful suspicion.

61

Doing harm is worse than not doing it, according to the “acts and omissions” principle, which influences conversations about moral responsibility. Some people believe that protecting innocent people should come before protecting others. In this instance, it suggests that monitoring methods should be avoided if they create irrational suspicions, even if they reduce the number of false convictions. Good surveillance can lower false suspicions and increase security for serious crimes. Despite the fact that this study discusses these benefits and offers suggestions, those who criticize surveillance usually overlook potential non-safety advantages.

62

Legal

Reforms and Safeguards

As surveillance technologies continue to advance, it’s becoming clear that current legal frameworks are no longer adequate to address the privacy concerns and civil liberties threats these systems present. Tools like CCTV, facial recognition, and data collection technologies are often implemented without proper supervision, which creates a dangerous disparity between public safety and the protection of individual freedoms. This lack of regulation can lead to situations where individuals are treated as suspects without any solid proof, threatening the presumption of innocence and increasing the risk of wrongful prosecution. The implementation of legal actions is essential, this is clear to address these pressing critical problems. First and foremost, we must create impartial oversight bodies to secure that surveillance technologies are used in an ethical and transparent manner. These agencies should have the authority to systematic checks and carry out research, ensuring that new surveillance technologies do not infringe violate individual rights or personal freedoms before they are implemented. However, it is important to realize that the efficacy of these measures’ hinges on rigorous execution. Although challenges may occur, the commitment to safeguarding civil liberties must remain unwavering, because such safeguards are fundamental to a just society. Comprehensive oversight of data collection methods is also essential. Monitoring technologies should only compile data that is directly connected with preventing criminal behavior. This approach could reduce the risk of unnecessary surveillance; however, it might still lead to the incorrect identification of innocent people as a due to inaccurate information. Furthermore, individuals ought to have the right to examine and dispute the records that have been created about their actions, because this would allow them to challenge unfair monitoring practices. Liability constitutes an essential part of these activities. Clear rules concerning the duration of information collection should be established; individuals must also be alerted when they are under monitoring. This transparency permits individuals to probe and assess monitoring strategies. However, it also diminishes the probability that these systems would be exploited for purposes such as population control or political manipulation. Although some might contend that monitoring is unnecessary, it remains crucial because it nurtures a sense of trust between individuals and the entities that regulate them. New monitoring systems can indeed enhance public protection; however, they must not infringe violate basic rights. In order to maintain the legal presumption of non-guilt, legislation ought to be updated to achieve an equilibrium between secrecy and security. We must confirm that monitoring does not in any way weaken this essential fundamental law. Ultimately, global collaboration is essential. Nations must work together to establish worldwide benchmarks for surveillance protocols in order to make certain that they serve the public, without transforming into instruments of control. However, by uniting their efforts, countries can craft develop legal structures that protect fundamental and personal freedoms, while simultaneously allowing surveillance to enhance security. Although challenges exist, this collaboration is critical, because it fosters a safer environment for everyone involved.

Discussion

The aim of this research was to explore how the presumption of innocence is influenced in various international scenarios by mass surveillance systems like CCTV, facial detection and digital surveillance. According to our study, although these technologies are frequently presented as tools for preventing illegal acts, they may potentially weaken the core legal presumption of innocence unless declared guilty.

63

The goal of this study was to analyze how the legal presumption of non-guilt is affected in a variety of cross-border contexts by comprehensive observation methods, such as CCTV, web monitoring, and face analysis software. Our study suggests that these technologies may also weaken the fundamental legal principle of innocence until proved, despite the fact that they are often presented as ways to reduce criminal activities.

64

Results in Context with Objectives

Findings in Relation to the Goals salts Linked to Objectives

The primary goal of the study was to understand the connection between civil liberties and, in particular, the presumption of innocence, and widespread tracking. Case research conducted in the United States, China, Russia, and the United Kingdom have shown that people are often regarded as suspects based only on monitoring records. In the UK, the pervasive deployment of CCTV creates a culture in which people feel constantly observed, which leads to self-censorship and a reduction in civil freedoms.

65

Similarly, in a related manner, the US’s PRISM program collects information without bias, which creates privacy problems and the risk for innocent persons to be mistakenly prosecuted without completing the proper due procedure.

66

Comparison with Previous Studies

This research builds on and confirms the results of researchers such as Lyon (2018);

67

Murakami Wood & Webster (2019),

68

who have long highlighted the fundamental conflict between safety, as implemented by these scholars, and individual freedom in relation to control. But the paper was wrong to gather what seems to be a relatively novel concept: Connect monitoring practices directly to the legal presumption of non-guilt. Although this has received limited focus in the earlier research of surveillance, which focused mainly on the privacy or security strategies to the problem, many challenges can arise regarding the ethical and legal outcomes of surveillance for the justice framework.

Study Contributions

The aim of this study is to integrate the broader discussion on surveillance by merging the assumption of innocence. Although the presumption of guiltlessness has often been considered a legal protection, this research clarifies the way it nestles alongside civil freedoms and surveillance strategies—while also pointing out the risks caused by unrestrained data gathering.

69

It also recommends many legislative steps, which can help ensure a balance between safety and privacy (e.g., setting up establishing impartial monitoring authorities or implementing data collection practices).

70

Study Limitations

There are a number of

challenges with the study. A key limitation is the utilization of pre-collected

information that may generally be unable to represent the range of viewpoints

and situations relevant to stakeholders impacted by surveillance. This was

heightened as data from neighboring authoritarian countries often had to be

omitted due to political limitations preventing analysis of controlled nations.

71

Third, since most case studies concentrated on countries with advanced monitoring

systems, the results may not indicate the situations of other countries with weaker

or less entrenched monitoring systems.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the impacts of widespread tracking on individual freedoms and the presumption of innocence in the US, UK, China, and Russia. Even if surveillance is often considered to be a necessary condition for safety and crime control, it comes at a high risk to personal freedoms, especially in the absence of effective control. Ubiquitous CCTV in the UK has weakened public confidence, leading to self-monitoring and fear. The US PRISM program caused severe privacy breaches as well as false accusation issues. In China, the Social Credit System showed the way behaviors are managed by monitoring and, consequently, harsh penalties for wrong data. Facial recognition at protests in Russia raised concerns about wrongful convictions and political repression.

These findings point out how we need good laws legal measures and worldwide protocols to stop these nosy practices. To defend people’s freedoms, we need to be responsible, clear and keep information secure. Future studies should involve the people affected and legal experts to get a better insight of how surveillance affects the idea that everyone’s innocent until proven guilty. If we don’t set up the right global frameworks, we might end up damaging the basic principles of democracy. This could make things lean too much towards societal protection instead of individual liberties.

To make sure surveillance technology works effectively without monitoring the principle, freedom of innocence until proven guilty, we need a thorough framework.

References

Alan Bryman, Social Research Methods (5th ed., Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Amnesty Int’l, Data Privacy and Surveillance in China: The Impact of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) (2022). https://www.amnesty.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Amnesty Int’l, Misuse of Facial Recognition Technology in Russia: A Report on Wrongful Detentions (2023). https://www.amnesty.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Harvard Univ. Press, 2002).

Brian Stewart, Balancing Security and Privacy in the Digital Age (Routledge, 2014).

Cameron Kerry, Privacy in the Age of Big Data: Analyzing Legal Implications (Brookings Inst. Press, 2020).

Christian Fuchs, Social Media: A Critical Introduction (2d ed., SAGE Publ’ns, 2017).

Colin J. Bennett & Charles D. Raab, The Privacy Advocates: Resisting the Spread of Surveillance (MIT Press, 2018).

Daniel J. Solove, Understanding Privacy (Harvard Univ. Press, 2021).

David Johnston, Surveillance Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy, 29 Pub. Culture 48 (2017).

David Lyon, Surveillance Studies: The New Era of Digital Oversight (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108768178

David Murakami Wood & William Webster, Surveillance and Society: Legal and Ethical Challenges (Routledge, 2019).

Edward Snowden, Permanent Record (Metropolitan Books 2013).

Erin G. Mistretta et al., Resilience Training for Work-Related Stress Among Health Care Workers: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing In-Person and Smartphone-Delivered Interventions, 60 J. Occupational & Envtl. Med. 559, 559-565 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001285

Eur. Ct. H.R., Privacy and Surveillance in Europe: Legal Guidelines (2008).

Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State (Metropolitan Books, 2014).

Human Rights Watch, China’s Social Credit System: Impacts on Civil Liberties (2022). https://www.hrw.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Info. Comm’r’s Off., Impact of the Investigatory Powers Act on Data Privacy (2022). https://ico.org.uk (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

James Campbell, Surveillance, Power, and the Politics of Freedom (Univ. of Toronto Press, 2010).

Jonathan Kimmelman, Risk and Consent in Clinical Trials, 10 J. Bioethics 150 (2000).

Joop J. Hox & Hennie R. Boeije, Data Collection, Primary vs. Secondary, in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement 593 (2005).

Kirstie Hadjimatheou, Surveillance and the Presumption of Innocence, 41 J.L. & Soc’y 30 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2014.00659.x

Lorelli S. Nowell et al., Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria, 16 Int’l J. Qual. Methods 1 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

Metropolitan Police Service, CCTV Misidentification Report (2020). https://www.met.police.uk/sd/stats-and-data/

Minxin Zeng, Social Credit and the Rule of Law in China, 6 Asian J.L. & Soc’y 123 (2019).

Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln, The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (4th ed., SAGE Publ’ns 2011).

P. Bou-Habib, Security, Profiling, and Equality, 11 Ethical Theory & Moral Prac. 149 (2008).

Pew Rsch. Ctr., Public Concerns About China’s Social Credit System: A Survey Analysis (2022). https://www.pewresearch.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Privacy Int’l, Facial Recognition and Wrongful Detentions in Russia (2020). https://www.privacyinternational.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Robert K. Yin, Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed., SAGE Publ’ns, 2018).

Rogier Creemers, China’s Social Credit System: A Practice of Control, 4 J. Chinese Governance 45 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2018.1443762

Rohan Samarajiva & Dan Weeramantry, Global Impacts of Mass Surveillance (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

Russ. Pub. Op. Rsch. Ctr., Survey on Public Concerns Regarding Facial Recognition Technology (2020).

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (PublicAffairs, 2019).

Stephen L. Roberts & Eleanor Marchant, Incorporating Non-Expert Evidence into Surveillance and Early Detection of Public Health Emergencies, Social Science in Humanitarian Action (2020). https://eprints.lse.ac.uk/104427/

Steven Feldstein, The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism: Implications for Civil Liberties, 12 Democracy & Digital Rights J. 89 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1353/ddr.2020.0010

Tara DeAngelis, The Psychology of Privacy Concerns, Am. Psychol. Ass’n. https://www.apa.org (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Toshio Yamagishi, Trust: The Evolutionary Game of Mind and Society (Springer, 2011).

U.N. Human Rts. Council, Report on the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age (2013).

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., Review of the USA FREEDOM Act’s Impact on Surveillance Practices (2018). https://www.gao.gov (last visited Nov. 18, 2024).

Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke, Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology, 3 Qual. Res. Psychol. 77 (2006), https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Notes

*

Research

article

1

David Lyon, Surveillance Studies: The New Era of Digital Oversight (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022).

2

David Murakami Wood & William Webster, Surveillance and Society: Legal and Ethical Challenges (Routledge, 2019).

3

Colin J. Bennett & Charles D. Raab, The Privacy Advocates: Resisting the Spread of Surveillance (MIT Press, 2018).

4

David Murakami Wood & William Webster, supra note 2.

5

Metropolitan Police Service, CCTV Misidentification Report (2020).

6

Info. Comm’r’s Off., Impact of the Investigatory Powers Act on Data Privacy (2022).

7

Steven Feldstein, The Rise of Digital Authoritarianism: Implications for Civil Liberties, 12 Democracy & Digital Rights J. 89 (2020).

8

U.S. Gov’t Accountability Off., Review of the USA FREEDOM Act’s Impact on Surveillance Practices (2018).

9

Rogier Creemers, China’s Social Credit System: A Practice of Control, 4 J. Chinese Governance 45 (2018).

10

Cameron Kerry, Privacy in the Age of Big Data: Analyzing Legal Implications (Brookings Inst. Press, 2020).

11

Minxin Zeng, Social Credit and the Rule of Law in China, 6 Asian J.L. & Soc’y 123 (2019).

12

Kerry, supra note 10.

13

Rohan Samarajiva & Dan Weeramantry, Global Impacts of Mass Surveillance (Oxford Univ. Press, 2020).

14

Human Rights Watch, China’s Social Credit System: Impacts on Civil Liberties (2022).

15

Amnesty Int’l, Data Privacy and Surveillance in China: The Impact of the Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL) (2022).

16

Human Rights Watch, supra note 14.

17

Amnesty Int’l, supra note 15.

18

Rohan Samarajiva & Dan Weeramantry, supra note 13.

19

Amnesty Int’l, Misuse of Facial Recognition Technology in Russia: A Report on Wrongful Detentions (2023).

20

Stephen L. Roberts & Eleanor Marchant, Incorporating Non-Expert Evidence into Surveillance and Early Detection of Public Health Emergencies, Social Science in Humanitarian Action (2020).

21

Lyon, supra note 1.

22

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (PublicAffairs, 2019).

23

Lyon, supra note 1.

24

Zuboff, supra note 22.

25

Daniel J. Solove, Understanding Privacy (Harvard Univ. Press, 2021).

26

Eur. Ct. H.R., Privacy and Surveillance in Europe: Legal Guidelines (2008).

27

Privacy Int’l, Facial Recognition and Wrongful Detentions in Russia (2020).

28

Solove, supra note 25.

29

U.N. Human Rts. Council, Report on the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age (2013).

30

Alan Bryman, Social Research Methods (5th ed., Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

31

Robert K. Yin, Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed., SAGE Publ’ns, 2018).

32

David Johnston, Surveillance Capitalism and the Crisis of Democracy, 29 Pub. Culture 48 (2017).

33

Joop J. Hox & Hennie R. Boeije, Data Collection, Primary vs. Secondary, in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement 593 (2005).

34

Virginia Braun & Victoria Clarke, Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology, 3 Qual. Res. Psychol. 77 (2006).

35

Lorelli S. Nowell et al., Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria, 16 Int’l J. Qual. Methods 1 (2017).

36

Lorelli S. Nowell et al., Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria, 16 Int’l J. Qual. Methods 1 (2017).

37

Joop J. Hox & Hennie R. Boeije, Data Collection, Primary vs. Secondary, in Encyclopedia of Social Measurement 593 (2005).

38

Norman K. Denzin & Yvonna S. Lincoln, The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (4th ed., SAGE Publ’ns 2011).

39

Yin, supra note 31.

40

U.N. Human Rts. Council, supra note 29.

41

Christian Fuchs, Social Media: A Critical Introduction (2d ed., SAGE Publ’ns, 2017).

42

Eur. Ct. H.R., supra note 26.

43

Fuchs, supra note 41.

44

Lyon, supra note 1.

45

Zuboff, supra note 22.

46

Lyon, supra note 1.

47

Erin G. Mistretta et al., Resilience Training for Work-Related Stress Among Health Care Workers: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing In-Person and Smartphone-Delivered Interventions, 60 J. Occupational & Envtl. Med. 559, 559-565 (2018).

48

Avishai Margalit, The Ethics of Memory (Harvard Univ. Press, 2002).

49

Kirstie Hadjimatheou, Surveillance and the Presumption of Innocence, 41 J.L. & Soc’y 30 (2014).

50

Lyon, supra note 1.

51

Glenn Greenwald, No Place to Hide: Edward Snowden, the NSA, and the U.S. Surveillance State (Metropolitan Books, 2014).

52

Toshio Yamagishi, Trust: The Evolutionary Game of Mind and Society (Springer, 2011).

53

Id.

54

Pew Rsch. Ctr., Public Concerns About China’s Social Credit System: A Survey Analysis (2022).

55

Yamagishi, supra note 52.

56

Id.

57

Margalit, supra note 48.

58

Tara DeAngelis, The Psychology of Privacy Concerns, Am. Psychol. Ass’n.

59

Greenwald, supra note 51.

60

P. Bou-Habib, Security, Profiling, and Equality, 11 Ethical Theory & Moral Prac. 149 (2008).

61

Jonathan Kimmelman, Risk and Consent in Clinical Trials, 10 J. Bioethics 150 (2000).

62

Lyon, supra note 1.

63

Lyon, supra note 1.

[64] Id.

64

Id.

65

Bennett & Raab, supra note 3.

66

Hadjimatheou, supra note 49.

67

Lyon, supra note 1.

68

Murakami Wood & Webster, supra note 2.

69

Zuboff, supra note 22.

70

Fuchs, supra note 41.

71

Lyon, supra note 1.

Author notes

aAutor de correspondencia / Correspondence author. E-mail: Malikbader2@gmail.com

Additional information

Cómo citar este artículo / How to cite this article: Mohamed Fathy Shehata

Diab, Gamal Sayed Khalifa Mohamed, Mohamed Bin Saud Alshammari, Alnammash Abdelrahman

Mohamed Yousuf, Malik Badir Alazzam, Public Relations, Criminal Analysis, Mass Monitoring, and Secrecy in the

Digital Age, 74 Vniversitas (2025). https://doi.org//10.11144/Javeriana.vj74.prca