Abstract

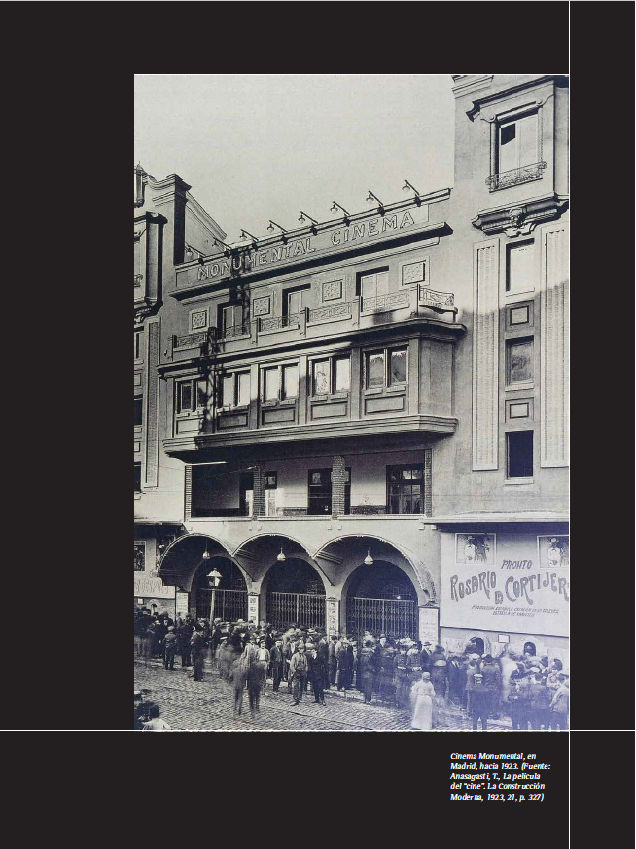

This text analyzes some elements that have characterized the architecture designed for cinematographic exploitation in Spain during the first decades of evolution of the show. Given the social, economic and cultural transformations that occurred simultaneously with the rise of “cinematographic representations” in fairs and later in many types of pavilions, this article aims to draw up an assessment of the evolution experienced by these spaces, and having led to the creation of a true architectural typology inspired by theatrical architecture. For this, this analysis is based on the study of some typologies developed particularly in the 1920s in Spain, while examining the projects of two leaders in the field of architecture for cinema: Teodoro Anasagasti and Luis Gutiérrez Soto. As for the buildings of Anasagasti, one will find mainly the presence of a “Beaux-Arts style”; and those of Gutiérrez Soto, we will rather see a spirit of avant-garde accompanied by a rationalism still emerging in Spain at that time.

AAVV. (1997). Catálogo de Luis Gutiérrez Soto. Exposición organizada por la Dirección General de la Vivienda, la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo del Ministerio de Fomento en colaboración con la fundación cultural COAM. Madrid:

Ministerio de Fomento, D.L.

AAVV. (1995). Historia del cine español. Madrid: Cátedra.

AAVV. (2011). Registro del Docomomo Ibérico: Ocio, deporte, comercio, turismo y transporte, 1925-1965. Barcelona: Fundación Caja de Arquitectos.

Anasagasti, T. (1919). El cine moderno. La Construcción Moderna, XVII(3).

Anasagasti, T. (1923). Características del cine. La Construcción Moderna, n. XX(21), 12-18.

Baldellou, M. Á. (1973). Luis Gutiérrez Soto, Colección Artistas Españoles Contemporáneos. Madrid: Dirección General de Bellas Artes, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia.

Cabero, J.A. (1949). Historia de la cinematografía española: once jornadas 1896-1948. Madrid: Gráficas Cinema.

Cámara, J. F. (2008). Las primeras salas para cinematógrafo en la ciudad: tres modos constructivos. Boletín Informativo del Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Alicante, 64.

Castillo, A. & Azorín V. (2009). Las revistas técnicas como base documental para la recuperación de un patrimonio olvidado: el caso de las salas de cine españolas Informes de la Construcción, 61, 515.

Castro, J. L. (1995). La Coruña y el cine. 100 años de historia. 1896-1936. Oleiros: Vía Láctea Editorial.

Castro, A. (2011). De Odeón a Calderón. El teatro que sustituyó al convento de la Trinidad. Ilustración de Madrid, 20, 201-2016.

Chueca, F. (2001). Historia de la Arquitectura Española, Edad Moderna Edad Contemporánea. Tomo II. Ávila: Fundación cultural Santa Teresa.

Cortés, J. (1992). El Racionalismo Madrileño. Madrid: Colegio Oficial de Arquitectos de Madrid.

Cueva, J.R. (2009, marzo 3). El Iris. La Nueva España- Diario Independiente de Asturias. Recuperado de http://www.lne.es/aviles/2009/03/03/iris/731567.html

Da Rocha, O. (2009). El modernismo en la arquitectura madrileña: génesis y desarrollo de una opción ecléctica. Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas.

De La Iglesia, F., Moreno, J.R., Pérez, M. & Ruiz, A. (1990). Arquitectura teatral y cinematográfica. Andalucía 1800-1990. Sevilla: Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura y Medio Ambiente.

De La Madrid, J.C. (1996). Primeros tiempos del cinematógrafo en España. Oviedo: TREA.

Domènech, L. (1878). En busca de una arquitectura nacional. La Renaixença, 4.

Donosty, J.M. (1924). Anasagasti y su gran cinematógrafo. La Construcción Moderna, 1.

El Palacio de la música. (1926). Revista Nacional de Arquitectura.

Etlin, R. A. (1989). Turin 1902: The Search for a Modern Italian Architecture. The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, 13 94-109. https://doi.org/10.2307/1504049

Fernández, Á. (1988). L. Arquitectura teatral en Madrid, del corral de comedias al cinematógrafo.

Madrid: Editorial El Avapies. Gubern, R. (1995). Historia del cine español. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra S.A.

Gutiérrez, L. (1927). Cine del Callao. Revista Nacional de Arquitectura, 94.

Gutiérrez, L. A. (1986). Arquitectura moderna y cine: su estructura comparada como principio objetivo para la comprensión y creación arquitectónica (Tesis Doctoral). Madrid.

Gutiérrez Soto, L. (1927). El cine del Callao. Arquitectura, 2, 61.

Lacloche, F. (1981). Architectures de cinemas. Collection architecture ‘les bâtiments’. Paris: Éditions du Moniteur.

Martin, R. & Vázquez, A. (1994). Del New England a los Goya: casi un siglo de cine en Ferrol. Galicia: Cuadernos Ferrol Análisis.

Martínez, J. (1992). Los Primeros veinticinco años de cine en Madrid: 1896-1920. Madrid: Filmoteca Española, Instituto de la Cinematografía y de las Artes Audiovisuales, Ministerio de Cultura.

Martínez, A. (1997). De cinematógrafo a los multicines: arquitectura para el séptimo arte en Alicante. Canelobre, (35-36), 43-62.

Melnick, R. & Fuchs, A. (2004). Cinema Treasures, A New Look at Classic Movie Theaters. Jackson: MIB Publishing Company.

Mendelsohn, E. (1929). El Cine Universum en Berlín. Arquitectura, 2, 67-68.

Mierendorff, C. (1965). Carlo Mierendorff. Eine Einführung in sein Werk und eine Auswahl von Fritz Usinger. Wiesbaden: Usinger Fritz.

Mierendorff, C. (1920). Hätte ich das Kino!. Berlín: Erich Reiß Verlag.

Neufert, E. (2006). Arte de Proyectar en Arquitectura. Madrid: Ed. Gustavo Gili S.A.

Pehnt, W. (1975). La arquitectura expresionista. Madrid: Ed. Gustavo Gili S.A.

Pérez, J. (1990). Art Decó en España. Madrid: Cátedra.

Puebla, J. (2002). Neovanguardias y representación arquitectónica: La expresión innovadora del proyecto contemporáneo. Barcelona: Ediciones UPC.

Ruszkowski, A. (1946). Cinema, Art Nouveau. Lyon: Editions Penser Vrai. Real Cinema” y “Cine Madrid-París” (Homenaje Anasagasti)”, Revista Arquitectura (1983) pp. 16-18 y pp. 40-43.

Schael, H. (1956). Idee und Form in Theaterbau des 19. und 20. Jährhunderts. Conferencia.

Colonia.

Stephan, R. (2004). Erich Mendelsohn, 1887-1953. Milán: Electra.

Tielve García, N. (2002). El Modernismo en Gijón, Rutas y paseos. Gijón: Gobierno del Principado

de Asturias.

Torras, J. (1972, septiembre 30). ¡Al Iris con los coches d’en Pujol!. La Vanguardia.

Urrutia, Á. (1997). Arquitectura española del siglo XX. Madrid: Ediciones Cátedra S.A.

Vergnes, E. (1925). Cinémas. Vues extérieures et intérieures, details, plans. Paris: Librairie Générale de l’Architecture et des Arts Décoratifs.

Wilms, F. (1928). Lichtspieltheaterbauten. Berlín: E. Wasmuth.

Zucker, P. (1926). Theater und Lichtspielhauser. Berlín: E. Wasmuth.

Apuntes is registered under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License. Thus, this work may be reproduced, distributed, and publicly shared in digital format, as long as the names of the authors and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana are acknowledged. Others are allowed to quote, adapt, transform, auto-archive, republish, and create based on this material, for any purpose (even commercial ones), provided the authorship is duly acknowledged, a link to the original work is provided, and it is specified if changes have been made. Pontificia Universidad Javeriana does not hold the rights of published works and the authors are solely responsible for the contents of their works; they keep the moral, intellectual, privacy, and publicity rights.

Approving the intervention of the work (review, copy-editing, translation, layout) and the following outreach, are granted through an use license and not through an assignment of rights. This means the journal and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana cannot be held responsible for any ethical malpractice by the authors. As a consequence of the protection granted by the use license, the journal is not required to publish recantations or modify information already published, unless the errata stems from the editorial management process. Publishing contents in this journal does not generate royalties for contributors.